Urological Infections

Urosepsis, prostatitis and HPV

Part 2

Comprehensive Review Article

Prof. Dr. Semir. A. Salim. Al Samarrai

Urosepsis:

- Introduction

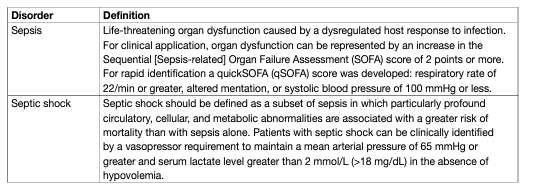

Patients with urosepsis should be diagnosed at an early stage, especially in the case of a cUTI. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), characterised by fever or hypothermia, leukocytosis or leukopenia, tachycardia and tachypnoea, has been recognised as a set of alerting symptoms [1,2]; however, SIRS is no longer included in the recent terminology of sepsis [3] (Table 1).

Table 1. Definition and criteria of sepsis and septic shock

Mortality is considerably increased the more severe the sepsis is. The treatment of urosepsis involves adequate life-supporting care, appropriate and prompt antimicrobial therapy, adjunctive measures and the optimal management of urinary tract disorders [4]. Source control by decompression of any obstruction and drainage of larger abscesses in the urinary tract is essential [4]. Urologists are recommended to treat patients in collaboration with intensive care and infectious diseases specialists. Urosepsis is seen in both community-acquired and healthcare associated infections. Nosocomial urosepsis may be reduced by measures used to prevent nosocomial infection, e.g. reduction of hospital stays, early removal of indwelling urinary catheters, avoidance of unnecessary urethral catheterization, correct use of closed catheter systems, and attention to simple daily aseptic techniques to avoid cross-infection. Sepsis is diagnosed when clinical evidence of infection is accompanied by signs of systemic inflammation, presence of symptoms of organ dysfunction and persistent hypotension associated with tissue anoxia (Table 1).

- Epidemiology, aetiology and pathophysiology

Urinary tract infections can manifest from bacteriuria with limited clinical symptoms to sepsis or severe sepsis, depending on localised and potential systemic extension. It is important to note that a patient can move from an almost harmless state to severe sepsis in a very short time. Mortality rates associated with sepsis vary depending on the organ source [5] with urinary tract sepsis generally having a lower mortality than that from other sources [6]. Sepsis is more common in men than in women [7]. In recent years, the overall incidence of sepsis arising from all sources has increased by 8.7% per year [5], but the associated mortality has decreased, which suggests improved management of patients (total in-hospital mortality rate fell from 27.8% to 17.9% from 1995 to 2000) [8]. Although the rate of sepsis due to Gram-positive and fungal organisms has increased, Gram-negative bacteria remain predominant in urosepsis [9,10]. In urosepsis, as in other types of sepsis, the severity depends mostly upon the host response. Patients who are more likely to develop urosepsis include elderly patients, diabetics, immunosuppressed patients, such as transplant recipients and patients receiving cancer chemotherapy or corticosteroids. Urosepsis also depends on local factors, such as urinary tract calculi, obstruction at any level in the urinary tract, congenital uropathy, neurogenic bladder disorders, or endoscopic manoeuvres. However, all patients can be affected by bacterial species that are capable of inducing inflammation within the urinary tract.

- Diagnostic evaluation

For diagnosis of systemic symptoms in sepsis either the full Sequential [Sepsis-related] Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score, or the quickSOFA score should be applied (Table 1). Microbiology sampling should be applied to urine, two sets of blood cultures [11], and if appropriate drainage fluids. Imaging investigations, such as sonography and CT-scan should be performed early [12].

- Physiology and biochemical markers

E. coli remains the most prevalent micro-organism. In several countries, bacterial strains can be resistant or multi-resistant and therefore difficult to treat [10]. Most commonly, the condition develops in compromised patients (e.g. those with diabetes or immunosuppression), with typical signs of generalised sepsis associated with local signs of infection.

- Cytokines as markers of the septic response

Cytokines are involved in the pathogenesis of sepsis [6]. They are molecules that regulate the amplitude and duration of the host inflammatory response. They are released from various cells including monocytes, macrophages and endothelial cells, in response to various infectious stimuli. The complex balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory responses is modified in severe sepsis. An immunosuppressive phase follows the initial pro-inflammatory mechanism. Sepsis may indicate an immune system that is severely compromised and unable to eradicate pathogens or a non-regulated and excessive activation of inflammation, or both. Genetic predisposition is a probable explanation of sepsis in several patients. Mechanisms of organ failure and death in patients with sepsis remain only partially understood [6].

- Biochemical markers

Procalcitonin is the inactive pro-peptide of calcitonin. Normally, levels are undetectable in healthy humans. During severe generalised infections (bacterial, parasitic and fungal) with systemic manifestations, procalcitonin levels rise [13]. In contrast, during severe viral infections or inflammatory reactions of non-infectious origin, procalcitonin levels show only a moderate or no increase. Mid-regional proadrenomedulline is another sepsis marker. Mid-regional proadrenomedullin has been shown to play a decisive role in the induction of hyperdynamic circulation during the early stages of sepsis and progression to septic shock [14]. Procalcitonin monitoring may be useful in patients likely to develop sepsis and to differentiate from a severe inflammatory status not due to bacterial infection [13,15]. In addition, serum lactate is a marker of organ dysfunction and is associated with mortality in sepsis [16]. Serum lactate should therefore also be monitored in patients with severe infections.

Disease management:

- Prevention

Septic shock is the most frequent cause of death for patients hospitalised for community-acquired and nosocomial infection (20-40%). Urosepsis treatment requires a combination of treatment including source control (obstruction of the urinary tract), adequate life-support care, and appropriate antimicrobial therapy [6,12]. In such a situation, it is recommended that urologists collaborate with intensive care and infectious disease specialists for the best management of the patient.

- Preventive measures of proven or probable efficacy

The most effective methods to prevent nosocomial urosepsis are the same as those used to prevent other nosocomial infections [17,18] they include:

• Isolation of patients with multi-resistant organisms following local and national recommendations.

• Prudent use of antimicrobial agents for prophylaxis and treatment of established infections, to avoid selection of resistant strains. Antibiotic agents should be chosen according to the predominant pathogens at a given site of infection in the hospital environment.

• Reduction in hospital stay. Long inpatient periods before surgery lead to a greater incidence of nosocomial infections.

• Early removal of indwelling urethral catheters, as soon as allowed by the patient’s condition. Nosocomial UTIs are promoted by bladder catheterisation as well as by ureteral stenting [19]. Antibiotic prophylaxis does not prevent stent colonisation, which appears in 100% of patients with a permanent ureteral stent and in 70% of those temporarily stented.

• Use of closed catheter drainage and minimisation of breaks in the integrity of the system, e.g. for urine sampling or bladder wash-out.

• Use of least-invasive methods to release urinary tract obstruction until the patient is stabilised.

• Attention to simple everyday techniques to assure asepsis, including the routine use of protective disposable gloves, frequent hand disinfection, and using infectious disease control measures to prevent cross-infections.

- Appropriate peri-operative antimicrobial prophylaxis

The potential side effects of antibiotics must be considered before their administration in a prophylactic regimen.

- Treatment

Early goal-directed resuscitation was initially shown to improve survival for emergency department patients presenting with septic shock in a randomised, controlled, single-centre study [20]. However, follow-up studies in an improved emergency medicine background have not achieved positive effects with this strategy [21–23]. An individual patient data meta-analysis of the later three multicentre trials concluded that early goal-directed therapy did not result in better outcomes than usual care and was associated with higher hospitalisation costs [24].

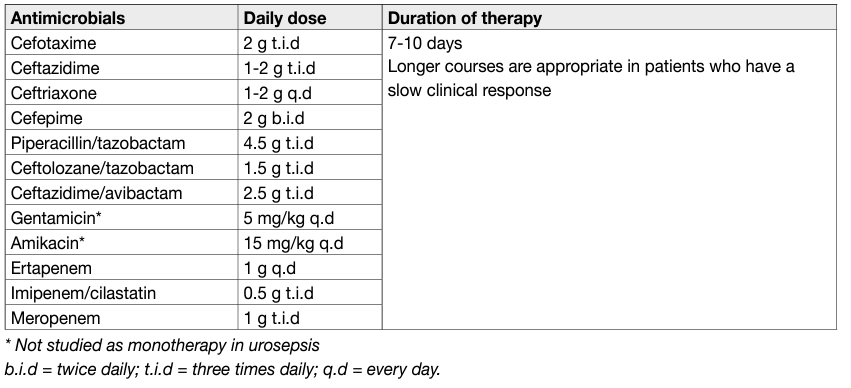

- Antimicrobial therapy

Initial empiric antimicrobial therapy should provide broad antimicrobial coverage against all likely causative pathogens and should be adapted on the basis of culture results, once available [4,12]. The dosage of the antimicrobial substances is of paramount importance in patients with sepsis syndrome and should generally be high, with appropriate adjustment for renal function [4]. Antimicrobials must be administered no later than one hour after clinical assumption of sepsis [4].

- Adjunctive measures

The most important adjunctive measures in the management of sepsis are the following [4,12]:

• fluid therapy with crystalloids, or albumin, if crystalloids are not adequately increasing blood pressure: passive leg raising-induced changes in cardiac output and in arterial pulse pressure are predictors of fluid responsiveness in adults [25];

• as vasopressors norepinephrine should be used primarily, dobutamine in myocardial dysfunction;

• hydrocortisone should be given only if fluid and vasopressors do not achieve a mean arterial pressure of > 65 mmHg;

• blood products should be given to target a haemoglobin level of 7-9 g/dL;

• mechanical ventilation should be applied with a tidal volume 6 mL/kg and plateau pressure < 30 cm H2O and a high positive end-expiratory pressure;

• sedation should be given minimally neuromuscular blocking agents should be avoided;

• glucose levels should be targeting at < 180 mg/dL;

• deep vein thrombosis prevention should be given with low-molecular weight heparin subcutaneously;

• stress ulcer prophylaxis should be applied in patients at risk, using protone pump inhibitors;

• enteral nutrition should be started early (< 48 hours).

In conclusion, sepsis in urology remains a severe situation with a considerable mortality rate. A recent campaign, ‘Surviving Sepsis Guidelines’, aims to reduce mortality by 25% in the next years [4,12,26]. Early recognition of the symptoms may decrease the mortality by timely treatment of urinary tract disorders, e.g. obstruction, or urolithiasis. Adequate life-support measures and appropriate antimicrobial treatment provide the best conditions for improving patient survival. The prevention of sepsis is dependent on good practice to avoid nosocomial infections and using antimicrobial prophylaxis and therapy in a prudent and well accepted manner.

Table 2: Suggested regimens for antimicrobial therapy for urosepsis.

Urethritis:

- Introduction

Urethritis can be of either infectious or non-infectious origin. Inflammation of the urethra presents usually with LUTS and must be distinguished from other infections of the lower urinary tract. Urethral infection is typically spread by sexual contact.

- Epidemiology, aetiology and pathogenesis

From a therapeutic and clinical point of view, gonorrhoeal urethritis (GU) caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae must be differentiated from non-gonococcal urethritis (NGU). Non-gonococcal urethritis is a non-specific diagnosis that can have many infectious aetiologies. Causative pathogens include Chlamydia trachomatis, Mycoplasma genitalium, Ureaplasma urealyticum and Trichomonas vaginalis. The role of Ureaplasma spp. as urethritis causative pathogens is controversial. Recent data suggests that U. urealyticum, but not U. parvum is an aetiological agent in NGU [27]. The prevalence of isolated causative pathogens is: C. trachomatis 11-50%; M. genitalium 6-50%; Ureaplasmas 5-26%; T. vaginalis 1-20%; and adenoviruses 2-4% [28]. Causative agents either remain extracellularly on the epithelial layer or penetrate into the epithelium (N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis) and cause pyogenic infection. Although arising from urethritis, chlamydiae and gonococci can spread further through the urogenital tract to cause epididymitis in men or cervicitis, endometritis and salpingitis in women [29]. Mucopurulent or purulent discharge, dysuria and urethral pruritus are symptoms of urethritis. However, many infections of the urethra are asymptomatic.

- Diagnostic evaluation

In symptomatic patients the diagnosis of urethritis can be made based on the presence of any of the following criteria [28,29]:

• Mucoid, mucopurulent, or purulent urethral discharge.

• Gram or methylene-blue stain of urethral secretions demonstrating inflammation. Five or more polymorphonuclear leucocytes (PMNL) per high power field (HPF) is the historical cut-off for the diagnosis of urethritis. A threshold of > 2 PMNL/HPF was proposed recently based on better diagnostic accuracy [30,31–33], but this was not supported by other studies [34]. Therefore, in line with the 2016 European Guideline on the management of NGU [28] the use of > 5 PMNL/HPF cut-off level is recommended until the benefit of alternative cut-off levels is confirmed.

- The presence of > 10 PMNL/HPF in the sediment from a spun first-void urine sample or a positive leukocyte esterase test in first-void urine.

Evidence of urethral inflammation in the Gram stain of urethral secretions with gonococci located intracellularly as Gram-negative diplococci indicates GU. Non-gonococcal urethritis is confirmed when staining of urethral secretions indicates inflammation in the absence of intracellular diplococci. Clinicians should always perform point-of-care diagnostics (e.g. Gram staining, first-void urine with microscopy, leukocyte esterase testing) if available to obtain objective evidence of urethral inflammation and to guide treatment [28,29,35]. Recent studies showed that processing time of point-of-care diagnostics is highly relevant in terms of patient compliance and real-life applicability [36,37]. Men who meet the criteria for urethritis should be tested for C. trachomatis, M. genitalium and N. gonorrhoea with nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT), even if point-of-care tests are negative for gonorrhoeae [28,38]. The sensitivity and specificity of NAATs is better than that of any of the other tests available for the diagnosis of chlamydial and gonococcal infections [39,40]. The performance of first-catch urine is non-inferior to urethral swabs [40]. In case of delayed treatment, if a NAAT is positive for gonorrhoea, a culture using urethral swabs should be performed before treatment to assess the antimicrobial resistance profile of the infective strain [29]. N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis cultures are mainly used to evaluate treatment failures and monitor developing resistance to current treatment. Trichomonas spp. can usually be identified microscopically [29] or by NAATs [41]. Non-gonococcal urethritis is classified as persistent when symptoms do not resolve within three to four weeks following treatment. When this occurs NAATs should be performed for urethritis pathogens including T. vaginalis four weeks after completion of therapy [28,42].

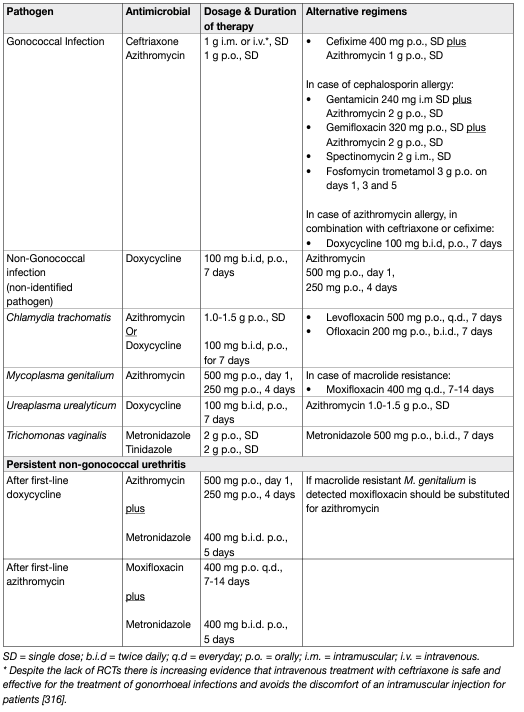

- Disease management

For severe urethritis empirical treatment should be started following diagnosis. If the patients’ symptoms are mild, delayed treatment guided by the results of NAATs is recommended. All sexual partners at risk should be assessed and treated whilst maintaining patient confidentiality [28,43].

- Gonococcal urethritis

For GU, a combination treatment using two antimicrobials with different mechanisms of action is recommended to improve treatment efficacy and to hinder increasing resistance to cephalosporins [29]. Ceftriaxone 1 g intramuscularly or intravenously with azithromycin 1 g single oral dose should be used as first-line treatment. Azithromycin is recommended because of its favourable susceptibility rates compared to other antimicrobials, good compliance with the single-dose regimen and the possibility of a C. trachomatis co-infection [29]. In case of azithromycin allergy, doxycycline can be used instead in combination with ceftriaxone or cefixime [29]. A 400 mg oral dose of cefixime is recommended as an alternative regimen to ceftriaxone; however, it has less favourable pharmacodynamics and may lead to the emergence of resistance [44,45]. A number of alternative regimens for the treatment of GU have been studied. In a randomised, open label, noncomparative clinical study dual treatment with a combination of intramuscular gentamicin 240 mg plus oral azithromycin 2 g (n=202) single doses and a combination of oral gemifloxacin 320 mg plus oral azithromycin 2 g (n=199) single doses were associated with microbiological cure rates of 100% and 99.5%, respectively [46]. A 2014 systematic review focusing on the use of single-dose intramuscular gentamicin concluded that there is insufficient data to support or refute the efficacy and safety of this regimen in the treatment of uncomplicated gonorrhoea [47]. In three prospective single arm studies enrolling men with GU the use of extended-release azithromycin 2 g single oral dose resulted in microbiological cure rates of 83% (n=36), 93.8% (n=122) and 90.9% (n=33), respectively [48,49,50]. However, azithromycin monotherapy is generally not recommended because of its effect on increasing macrolide resistance rates [29]. Intramuscular spectinomycin 2 g single dose shows microbiological cure rates above 96% [51,45] in urogenital gonorrhoeal infections; therefore, where available, it can be a valid treatment alternative. An open label, randomised trial compared oral fosfomycin trometamol 3 g on days one, three and five (n=60) with intramuscular ceftriaxone 250 mg plus oral azithromycin 1 g single dose (n=61) in men with uncomplicated GU. In the per-protocol analysis clinical and microbiologic cure rates were 96.8% and 95.3% respectively [52]. The worldwide increase in gonorrhoeal antimicrobial resistance and the emergence of multidrugresistant gonorrhoeal strains is a globally recognised healthcare crisis which emphasises the importance of guideline adherence [53,54,55].

- Non-gonococcal urethritis

For NGU without an identified pathogen oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for seven days should be used as first-line treatment. Alternatively, single dose oral azithromycin 500 mg day one and 250 mg days two to four can be used. This regimen provides better efficacy compared to azithromycin 1 g single dose for M. genitalium infections, in which azithromycin 1 g single dose treatment is associated with the development of increasing macrolide resistance significantly decreasing the overall cure rate [28,38,56,57]. However, a retrospective cohort study did not find significant difference between the extended and 1 g single dose azithromycin regimen regarding cure rates and the selection of macrolide resistance in M. genitalium urethritis [58]. If macrolide resistant M. genitalium is detected moxifloxacin 400 mg can be used for seven to fourteen days [28, 29,59]. In case of failure after both azithromycin and moxifloxacin treatment, pristinamycin (registered in France) is the only antimicrobial agent with documented activity against M. genitalium [38,60,61]. Josamycin 500 mg three times a day for ten days is used in Russia, but will not eradicate macrolideresistant strains [38]. For chlamydial urethritis azithromycin 1 g single dose and doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for seven days are both effective options [62]. A Cochrane review found that in men with urogenital C. trachomatis infection regimens with azithromycin are probably less effective than doxycycline for microbiological failure, however, there might be little or no difference for clinical failure [63]. Fluoroquinolones, such as ofloxacin or levofloxacin, may be used as second-line treatment only in selected cases where the use of other agents is not possible [64]. For U. urealyticum infections the efficacy of doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for seven days is similar to azithromycin 1 g single dose treatment [28,65]. For urethritis caused by T. vaginalis oral metronidazole or tinidazole 2 g single dose is recommended as first-line treatment. For treatment options for persistent or recurrent T. vaginalis infection refer to the review of Sena et al., [41]. In case of persistent NGU treatment should cover M. genitalium and T. vaginalis [28,29].

- Follow-up

Patients should be followed up for control of pathogen eradication after completion of therapy only if therapeutic adherence is in question, symptoms persist or reoccurrence is suspected. Patients should be instructed to abstain from sexual intercourse for seven days after therapy is initiated, provided their symptoms have resolved and their sexual partners have been adequately treated. Reporting and source tracing should be done in accordance with national guidelines and in cooperation with specialists in venereology, whenever required. Persons who have been diagnosed with a new STD should receive testing for other STDs, including syphilis and HIV [66].

Table 3: Suggested regimens for antimicrobial therapy for urethritis

Bacterial Prostatitis:

- Introduction

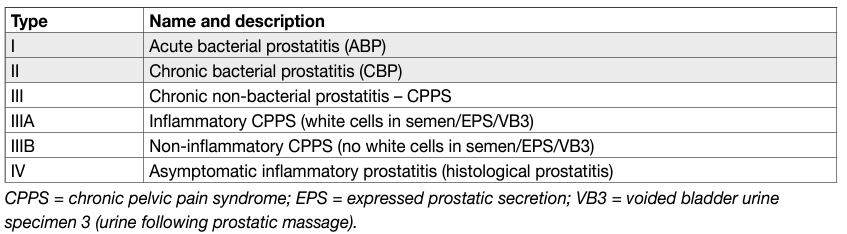

Bacterial prostatitis is a clinical condition caused by bacterial pathogens. It is recommended that urologists use the classification suggested by the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), in which bacterial prostatitis, with confirmed or suspected infection, is distinguished from chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS) (Table 4) [67–69].

Table 4: Classification of prostatitis and CPPS according to NIDDK/NIH [67–69]

- Evidence Summary

A systematic literature search from 1980 until June 2017 was performed. One systematic review [70], six RCTs [71–76], two narrative reviews [77,78], one prospective cohort study [79], two prospective cross-sectional studies [80,81], and one retrospective cohort study [73], were selected from 856 references. A retrospective study [82], investigated the potential role of unusual pathogens in prostatitis syndrome in 1,442 patients over a four-year period. An infectious aetiology was determined in 74.2% of patients; C. trachomatis, T. vaginalis and U. urealyticum infections were found in 37.2%, 10.5% and 5% of patients, respectively whilst E. coli infection was found in only 6.6% of cases. Cross sectional studies confirmed the validity of the Meares and Stamey test to determine the bacterial strain and targeted antibiotic therapies [80,81]. The evidence levels were good, in particular those regarding information on atypical strains, epidemiology and antibiotic treatments. A systematic review on antimicrobial therapy for CBP [70] compared multiple antibiotic regimens from eighteen selected studies enrolling a total of 2,196 patients. The role of fluoroquinolones as first-line agents was confirmed with no significant differences between levofloxacin, ciprofloxacin and prulifloxacin in terms of microbiological eradication, clinical efficacy and adverse events. The efficacy of macrolides and tetracyclines on atypical pathogens was confirmed. Randomised controlled trials on combined treatments [75,76] indicated that the combination of plants/herbal extracts or PDE5Is with antibiotics may improve quality of life and symptoms in patients with CBP; however, the number of enrolled patients was inadequate to obtain definitive conclusions. A review of treatment of bacterial prostatitis [77] indicated that the treatment of CBP is hampered by the lack of an active antibiotic transport mechanism into infected prostate tissue and fluids. The review underlined the potential effect of different compounds in the treatment of ABP and CBP on the basis of over 40 studies on the topic. One RCT compared the effects of two different metronidazole regimens for the treatment of CBP caused by T. vaginalis [74]. Metronidazole 500 mg three times daily for fourteen days was found to be efficient for micro-organism eradication in 93.3% of patients with clinical failure in 3.33% of cases. The evidence question addressed was: In men with NIDDK/NIH Category I or II prostatitis what is the best antimicrobial treatment strategy for clinical resolution and eradication of the causative pathogen?

- Epidemiology, aetiology and pathogenesis

Prostatitis is a common diagnosis, but less than 10% of cases have proven bacterial infection [83]. Enterobacterales, especially E. coli, are the predominant pathogens in ABP [84]. In CBP, the spectrum of species is wider and may include atypical micro-organisms [77]. In patients with immune deficiency or HIV infection, prostatitis may be caused by fastidious pathogens, such as M. tuberculosis, Candida spp. and other rare pathogens, such as Coccidioides immitis, Blastomyces dermatitidis, and Histoplasma capsulatum [85]. The significance of identified intracellular bacteria, such as C. trachomatis, is uncertain [86]; however, two studies have highlighted its possible role as a causative pathogen in CBP [87,88].

Diagnostic evaluation:

- History and symptoms

Acute bacterial prostatitis usually presents abruptly with voiding symptoms and distressing but poorly localised pain. It is often associated with malaise and fever. Transrectal prostate biopsy increases the risk of ABP despite antibiotic prophylaxis and antiseptic prevention procedures [71]. Chronic bacterial prostatitis is defined by symptoms that persist for at least three months [89–91]. The predominant symptoms are pain at various locations including the perineum, scrotum, penis and inner part of the leg as well as LUTS [67–69].

- Symptom questionnaires

In CBP symptoms appear to have a strong basis for use as a classification parameter [92]. Prostatitis symptom questionnaires have therefore been developed to assess severity and response to therapy [92,93]. They include the validated Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index (CPSI); however, its usefulness in clinical practice is uncertain [79].

- Clinical findings

In ABP, the prostate may be swollen and tender on DRE. Prostatic massage should be avoided as it can induce bacteraemia and sepsis. Urine dipstick testing for nitrite and leukocytes has a positive predictive value of 95% and a negative predictive value of 70% [94]. Blood culture and complete blood count are useful in ABP. Imaging studies can detect a suspected prostatic abscess [77]. In case of longer lasting symptoms CPPS as well as other urogenital and anorectal disorders must be taken into consideration. Symptoms of CBP or CPPS can mask prostate tuberculosis. Pyospermia and hematospermia in men in endemic regions or with a history of tuberculosis should trigger investigation for urogenital tuberculosis.

- Urine cultures and expressed prostatic secretion

The most important investigation in the evaluation of a patient with ABP is mid-stream urine culture [77]. In CBP, quantitative bacteriological localisation cultures and microscopy of the segmented urine and expressed prostatic secretion (EPS), as described by Meares and Stamey [95], are still important investigations to categorise clinical prostatitis [80,81]. Accurate microbiological analysis of samples from the Meares and Stamey test may also provide useful information on the presence of atypical pathogens such as C. trachomatis, T. vaginalis and U. urealiticum [82]. The two-glass test has been shown to offer similar diagnostic sensitivity to the four-glass test [96].

- Prostate biopsy

Prostate biopsies cannot be recommended as routine work-up and are not advisable in patients with untreated bacterial prostatitis due to the increased risk of sepsis.

- Other tests

Transrectal US may reveal endoprostatic abscesses, calcification in the prostate, and dilatation of the seminal vesicles; however, it is unreliable as a diagnostic tool for prostatitis [97].

- Additional investigations

- Ejaculate analysis

Performing an ejaculated semen culture improves the diagnostic utility of the four-glass test [80]; however, semen cultures are more often positive than EPS cultures in men with non-bacterial prostatitis [81]. Bladder outflow and urethral obstruction should always be considered and ruled out by uroflowmetry, retrograde urethrography, or endoscopy.

- First-void urine sample

First-void urine is the preferred specimen for the diagnosis of urogenital C. trachomatis infection in men by NAATs, since it is non-invasive and yet allows the detection of infected epithelial cells and associated C. trachomatis particles [98].

- Prostate specific antigen (PSA)

Prostate specific antigen is increased in about 60% and 20% of men with ABP and CBP, respectively [78]. The PSA level decreases after antibiotic therapy (which occurs in approximately 40% of patients) and correlates with clinical and microbiological improvement [72]. Measurement of free and total PSA adds no practical diagnostic information in prostatitis [99].

Disease management:

- Antimicrobials

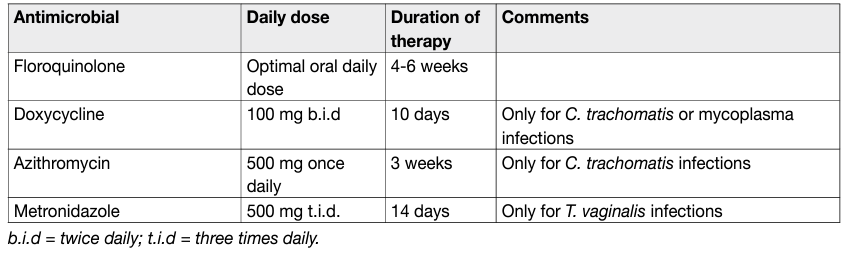

Antimicrobials are life-saving in ABP and recommended in CBP. Culture-guided antibiotic treatments are the optimum standard; however, empirical therapies should be considered in all patients with ABP. In ABP parenteral administration of high doses of bactericidal antimicOUSrobials, such as broadspectrum penicillins, a third-generation cephalosporin or fluoroquinolones, is recommended [349]. For initial therapy, any of these antimicrobials may be combined with an aminoglycoside [84–93, 100–104]. Ancillary measures include adequate fluid intake and urine drainage [105]. After normalisation of infection parameters, oral therapy can be substituted and continued for a total of two to four weeks [106]. Fluoroquinolones, despite the high resistance rates of uropathogens, are recommended as firstline agents in the empirical treatment of CBP because of their favourable pharmacokinetic properties [107], their generally good safety profile and antibacterial activity against Gram-negative pathogens including P. aeruginosa and C. trachomatis [70, 108]. However, increasing bacterial resistance is a concern. Azithromycin and doxycycline are active against atypical pathogens such as C. trachomatis and genital mycoplasmata [73,82]. Levofloxacin did not demonstrate significant clearance of C. trachomatis in patients with CBP [109]. Metronidazole treatment is indicated in patients with T. vaginalis infections [74]. Duration of fluoroquinolone treatment must be at least fourteen days while azithromycin and doxycycline treatments should be extended to at least three to four weeks [73,82]. In CBP antimicrobials should be given for four to six weeks after initial diagnosis [77]. If intracellular bacteria have been detected macrolides or tetracyclines should be given [70,107,110].

- Intraprostatic injection of antimicrobials

This treatment has not been evaluated in controlled trials and should not be considered [111,112].

- Combined treatments

A combination of fluoroquinolones with various herbal extracts may attenuate clinical symptoms without increasing the rate of adverse events [75]. However, a combination of fluoroquinolones with vardenafil did not improve microbiological eradication rates or attenuated pain or voiding symptoms in comparison with fluoroquinolone treatment alone [76].

- Drainage and surgery

Approximately 10% of men with ABP will experience urinary retention [113] which can be managed by uretheral or suprapubic catheterisation. However, recent evidence suggests that suprapubic catheterisation can reduce the risk of development of CBP [114]. In case of prostatic abscess, both drainage and conservative treatment strategies appear feasible [115]; however, the abscess size may matter. In one study, conservative treatment was successful if the abscess cavities were < 1 cm in diameter, while larger abscesses were better treated by single aspiration or continuous drainage [116].

Table 5: Suggested regimens for antimicrobial therapy for chronic bacterial prostatitis

Follow-up:

In asymptomatic post-treatment patient’s routine urinalysis and/or urine culture is not mandatory as there are no validated tests of cure for bacterial prostatitis except for cessation of symptoms [77]. In patients with persistent symptoms and repeated positive microbiological results for sexually transmitted infectious pathogens, microbiological screening of the patient’s partner/s is recommended. Antibiotic treatments may be repeated with a more prolonged course, higher dosage and/or different compounds [77].

Acute Infective Epididymitis:

- Epidemiology, Aetiology and Pathophysiology

Epididymitis is a common condition with incidence ranging from 25 to 65 cases per 10,000 adult males per year and can be acute, chronic or recurrent [117]. Acute epididymitis is clinically characterised by pain, swelling and increased temperature of the epididymis, which may involve the testis and scrotal skin. It is generally caused by migration of pathogens from the urethra or bladder that can be identified by appropriate diagnostics in up to 90% of patients [118]. Torsion of the spermatic cord (testicular torsion) is the most important differential diagnosis in boys and young men. The predominant pathogens isolated are Enterobacterales (typically E. coli), C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae [119]. Men who have anal intercourse and those with abnormalities of the urinary tract resulting in bacteriuria are at higher risk of epididymitis caused by Enterobacterales [120]. The mumps virus should be considered if there are viral prodromal symptoms and salivary gland enlargement. Tuberculous epididymitis may occur, typically as chronic epididymitis, in high-risk groups such as men with immunodeficiency and those from high prevalence countries, it frequently results in a discharging scrotal sinus. Brucella or Candida spp. are rare possible pathogens.

- Diagnostic Evaluation

Culture of a mid-stream specimen of urine should be performed and any previous urine culture results should be checked. Sexually transmitted infections including C. trachomatis or N. gonorrhoeae should be detected by NAAT on first-voided urine or urethral swab. A urethral swab or smear should be performed for Gram staining and culture of N. gonorrhoeae, when available [117,121,122]. Detection of these pathogens should be reported according to local procedures. All patients with probable sexually transmitted infections (STIs) should be advised to attend an appropriate clinic to be screened for other STIs. Men with Enterobacterales may require investigation for lower urinary tract abnormalities. If tuberculous epididymitis is suspected, three sequential early morning urine samples should be cultured for acid-fast bacilli (AFB) and sent for screening by NAAT for M. tuberculosis DNA [123]. If appropriate, prostate secretion, ejaculate, discharge from a draining scrotal fistula, as well as fine needle aspiration and biopsy specimens should be investigated using microscopy, AFB culture and NAAT. Scrotal US is more accurate for the diagnose of acute epididymitis than urinalysis alone [125] and may also be beneficial for the exclusion of other pathologies [125].

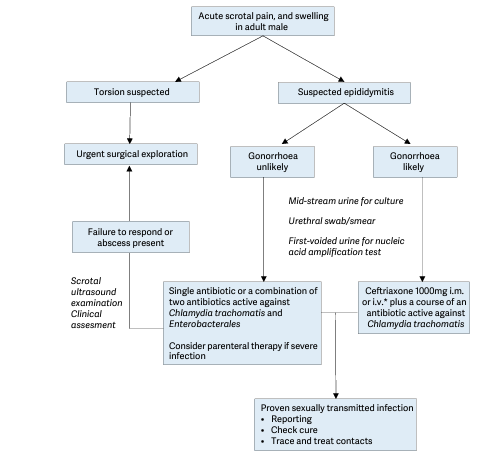

- Disease Management

Men with suspected STI should be informed of the risks to others and advised not to have sex until free of infection. Empirical antimicrobial therapy has to be chosen with consideration of the most probable pathogen and degree of penetration into the inflamed epididymis and may need to be varied according to local pathogen sensitivities and guidance. Generally, both C. trachomatis and Enterobacterales should be covered initially and the regimen modified according to pathogen identification. Doxycycline and some specific fluoroquinolones have good clinical and microbiological cure rates in patients with suspected C. trachomatis or M. genitalium and both achieve adequate levels in inflamed male genital tissues with oral dosing. Macrolide antibiotics such as azithromycin are effective against C. trachomatis but have not been tested in epididymitis; however, initial pharmacokinetic studies suggest that azithromycin may effectively penetrate epididymal tissue when given in multiple doses [126]. Fluoroquinolones remain effective for oral treatment of Enterobacterales although resistance is increasing and local advice should be sought. Fluoroquinolones should not be considered for gonorrhoea. Single high parenteral dose of a third-generation cephalosporin is effective against N. gonorrhoeae; current resistance patterns and local public health recommendations should guide choice of agent. Clinical response to antibiotics in men with severe epididymitis should be assessed after approximately three days. Men with likely or proven STI should be assessed at fourteen days to check cure and ensure tracing and treatment of contacts according to local public health recommendations.

Empiric antibiotic regimens from existing guidelines [29,121,127,128] consensus:

1. For men with acute epididymitis at low risk of gonorrhoea (e.g. no discharge) a single agent or combination of two agents of sufficient dose and duration to eradicate C. trachomatis and Enterobacterales should be used. Appropriate options are:

A. A fluoroquinolone active against C. trachomatis orally once daily for ten to fourteen days* OR

B. Doxycycline 200 mg initial dose by mouth and then 100 mg twice daily for ten to fourteen days* plus an antibiotic active against Enterobacterales** for ten to fourteen days*

2. For men with likely gonorrhoeal acute epididymitis a combination regimen active against Gonococcus and C. trachomatis must be used such as:

A. Ceftriaxone 1000 mg intramuscularly single dose plus doxycycline 200 mg initial dose by mouth and then 100 mg twice daily for ten to fourteen days*

3. For non-sexually active men with acute epididymitis a single agent of sufficient dose and duration to eradicate Enterobacterales should be used. Appropriate option is a fluoroquinolone by mouth once daily for ten to fourteen days*

*Depending upon pathogen identification and clinical response.

** A parenteral option will be required for men with severe infection requiring hospitalisation.

Surgical exploration may be required to drain abscesses or debride tissue. A comparative cohort study found that lack of separation of epididymis and testis on palpation and the presence of abscess on US may predict requirement for surgery following initial antibiotic treatment [129]. A cohort study found semen parameters may be impaired during epididymitis but recovered following successful treatment [130]. Comparative clinician cohort studies suggest adherence to guidelines for assessment and treatment of epididymitis is low, particularly by urologists compared to sexual health specialists [131] and by primary care physicians [132].

- Screening

A large cohort screening study for carriage of C. trachomatis including a randomly selected group of 5,000 men of whom 1,033 were tested showed no benefit in terms of reduction in risk of epididymitis over nine years of observation [133].

Figure 1: Diagnostic and treatment algorithm for men with acute epididymitis

i.m. = intramuscular; i.v. intravenously. * Despite the lack of RCTs there is increasing evidence that intravenous treatment with ceftriaxone is safe and effective for the treatment of gonorrhoeal infections and avoids the discomfort of an intramuscular injection for patients

Fournier’s Gangrene (Necrotising fasciitis of the perineum and external genitalia):

- Epidemiology, Aetiology and Pathophysiology

Fournier’s gangrene is an aggressive and frequently fatal polymicrobial soft tissue infection of the perineum, peri-anal region, and external genitalia [134]. It is an anatomical sub-category of necrotising fasciitis with which it shares a common aetiology and management pathway.

- Diagnostic Evaluation

Typically, there is painful swelling of the scrotum or perineum with sepsis [134]. Examination shows small necrotic areas of skin with surrounding erythema and oedema. Crepitus on palpation and a foul-smelling exudate occurs with more advanced disease. Patient risk factors for occurrence and mortality include being immunocompromised, most commonly diabetes or malnutrition, recent urethral or perineal surgery, and high body mass index (BMI). In up to 40% of cases, the onset is more insidious with undiagnosed pain often resulting in delayed treatment [135]. A high index of suspicion and careful examination, particularly of obese patients, is required. Computed tomography or MRI can help define para-rectal involvement, suggesting the need for bowel diversion [134].

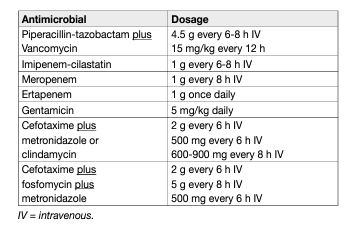

- Disease Management

The degree of internal necrosis is usually vastly greater than suggested by external signs, and consequently, adequate, repeated surgical debridement with urinary diversion by suprapubic catheter is necessary to reduce mortality [134]. Consensus from case series suggests that surgical debridement should be early (< 24 hours) and complete, as delayed and/or inadequate surgery may result in higher mortality [134]. Immediate empiric parenteral antibiotic treatment should be given that covers all probable causative organisms and can penetrate inflammatory tissue. A suggested regime would comprise a broad-spectrum penicillin or third-generation cephalosporin, gentamicin and metronidazole or clindamycin [134]. This can then be refined, guided by microbiological culture.

A systematic literature search from 1980 to July 2017 was performed. From 640 references one RCT [136], two systematic reviews [137,138], one narrative review [134], three registry studies [139–141], one prospective cohort study [142] and two retrospective comparative cohort studies with at least 25 patients [143,144] were selected. The three registry studies from the United States [139–141], found mortality rates of 10%, 7.5% and 5% from 650, 1,641 and 9,249 cases, respectively. Older age, diabetes and high BMI were associated with higher risk. A prospective cohort study showed that disease-specific severity scores did predict outcome, but were not superior to generic scoring systems for critical care [142]. The evidence questions addressed were:

1. What is the best antimicrobial treatment strategy to reduce mortality?

2. What is the best debridement and reconstruction strategy to reduce mortality and aid recovery?

3. Are there any effective adjuvant treatments that improve outcome?

Table 6: Suggested regimens for antimicrobial therapy for Fournier’s Gangrene of mixed microbiological aetiology adapted from [145].

Management of Human papilloma virus in men:

- Epidemiology

Human papilloma virus (HPV) is one of the most frequently sexually transmitted viruses encompassing both oncogenic (low- and high-risk variants) and non-oncogenic viruses. HPV16 is the most common oncogenic variant, detected in 20% of all HPV cases [146]. A recent meta-analysis revealed a prevalence of 49% of any type of HPV and 35% of high-risk HPV in men [147]. Similar to the female genital tract, half of all HPV infections in the male genital tract are co-infections (> 2 HPV strains) [148]. HPV presence is dependent on study setting. In men attending urological clinics HPV was detected in 6% of urine samples [149]. A meta-analysis reported seminal HPV in 4.5-15.2% of patients resulting in seminal HPV being associated with decreased male fertility [146]. A cross-sectional study of 430 men presenting for fertility treatment detected HPV in 14.9% of semen samples [150]. The presence of HPV in semen was not associated with impaired semen quality [150]. However, another systematic review reported a possible association between HPV and altered semen parameters, and in women possible miscarriage or premature rupture of the membrane during pregnancy [151]. HPV6 and/or 11 were the most common genotypes detected in an observational study of anogenital warts, whilst HPV16 is correlated with severity of anal cytology [152]. The incidence of non-oncogenic HPV infection has been shown to be higher in men than women [153]. In males, approximately 33% of penile cancers and up to 90% of anal cancers are attributed to high-risk HPV infections, primarily with HPV16 [154]. The EAU Penial Cancer Guidelines will publish a comprehensive update in March 2022 including the results of two systematic reviews on HPV and penile cancer. Oral HPV is associated with oropharyngeal carcinomas approximately 22.4%, 4.4% and 3.5% of oral cavity, oropharynx and larynx cancers, respectively are attributed to HPV [154]. Systematic reviews have reported prevalence rates of oral HPV from 5.5-7.7%, with HPV16 present in 1-1.4% of patients [155,156].

- Risk factors

Risk factors for HPV infection include early age of first sexual intercourse, sexual promiscuity, higher frequency of sexual intercourse, smoking and poor immune function [157–161]. Incidence and prevalence of overall HPV was considerably higher in men who have sex with men (MSM) compared to heterosexuals [155,158]. Overall, the prevalence of HPV in different sites seems to be higher in young, sexual-active adults compared to other population groups [157]. Stable sexual habits, circumcision and condom use are protective factors against HPV [147,161–165]. Added risk factors of oral HPV infection are alcohol consumption, poor oral hygiene and sexual behaviours (oral and vaginal) [155,157]. Positive HIV status, phimosis, and HPV status of the partner have also been associated with anogenital HPV status and decreased clearance in a number of studies [162].

- Transmission

HPV typically spreads by sustained direct skin-to-skin or mucosal contact, with vaginal, oral and anal sex being the most common transmission route [159]. In addition, HPV has been found on surfaces in medical settings and public environments raising the possibility of object-to-skin/mucosa transmission [166]. Further studies on nonsexual and non-penetrative sexual transmission are needed to understand the complexity of HPV transmission. HPV transmission may also be influenced by genotype, with a higher incidence of HPV51 and HPV52 and a high prevalence of HPV16 and HPV18 in the general and high-risk male population [159].

- Clearance

HPV time-to-clearance ranges from 1.3 to 42.1 months [167]. Clearance may be influenced by HPV genotype, patients’ characteristics and affected body site [158,162,167]. HPV16 has the highest incidence of high-risk HPV variants and has the lowest clearance across sites [162].

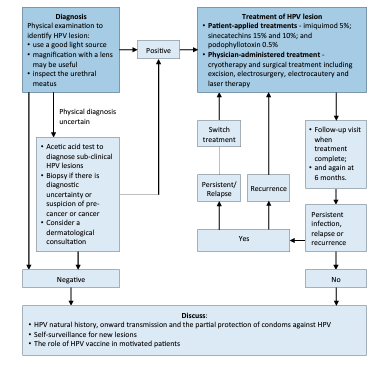

- Diagnosis

There is currently no approved test for HPV in men. Routine testing to check for HPV or HPV-related disease in men is not recommended. A physical examination to identify HPV lesions should be carried out. An acetic acid test to diagnose sub-clinical HPV lesions may be performed. If the diagnosis is uncertain or there is a suspicion of cancer a biopsy should be carried out. Intra-urethral condylomas are relatively uncommon and are usually limited to the distal urethral meatus [168,169]. Urethrocystoscopy may be used to diagnose the presence of intra-urethral or bladder warts [169]; however, there is no high-level evidence for the use of invasive diagnostic tools for localisation of intra-urethral HPV. For detailed recommendations on the diagnosis of anogenital warts please refer to the IUSTI-European guideline for the management of anogenital warts [170].

- Treatment of HPV related diseases

Approximately 90% of HPV infections do not cause any problems and are cleared by the body within two years. However, treatment is required when HPV infection manifests as anogenital warts to prevent the transmission of HPV-associated anogenital infection and to minimise the discomfort caused to patients [170]. Of the treatment options available only surgical treatment has a primary clearance rate approaching 100%.

- Treatments suitable for self-application

Patient-applied treatments include podophyllotoxin, salicylic acid, imiquimod, polyphenon E, 5-fluoracil and potassium hydroxide [170]. Imiquimod 5% cream showed a total clearance of external genital or perianal warts in 50% of immunocompetent patients [171] as well as in HIV positive patients successfully treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy [172]. A Cochrane review of published RCTs found imiquimod to be superior to placebo in achieving complete clearance of warts (RR: 4.03, 95% CI: 2.03–7.99) [173]. The recommended treatment schedule is imiquimod 5% cream applied to all external warts overnight three times each week for sixteen weeks [170]. In an RCT involving 502 patients with genital and/or perianal warts sinecatechins 15% and 10% showed a complete clearance of all baseline and newly occurring warts in 57.2% and 56.3% of patients, respectively vs. 33.7% for placebo [174]. In addition, sinecatechins 10% has been shown to be associated with lower short-term recurrence rates when used as sequential therapy after laser CO2 ablative therapy [175]. Sinecatechins is applied three times daily until complete clearance, or for up to sixteen weeks. Clearance rates of 36–83% for podophyllotoxin solution and 43–70% for podophyllotoxin cream have been reported [170]. A systematic review and meta-analysis confirmed the effectiveness of podophyllotoxin 0.5% solution relative to placebo (RR: 19.86, 95% CI: 3.88–101.65) [176]. Podophyllotoxin is self-applied to lesions twice daily for three days, followed by four rest days, for up to four or five weeks. An RCT has also shown potassium hydroxide 5% to be an effective, safe, and low-cost treatment modality for genital warts in men [177].

- Physician-administered treatment

Physician-administered treatments included cryotherapy (79-88% clearance rate; 25-39% recurrence rate), surgical treatment (61-94% clearance rate), including excision, electrosurgery, electrocautery and laser therapy (75% clearance rate) [178,179]. Physician-administered therapies are associated with close to 100% clearance rates, but they are also associated with high rates of recurrence as they often fail to eliminate invisible HPVinfected lesions [178,179]. No data about the superiority of one treatment over another are available. However, among all interventions evaluated in a recent systematic review and network meta-analysis, surgical excision appeared to be the most effective treatment at minimising risk of recurrence [180].

- Circumcision for reduction of HPV prevalence

Male circumcision is a simple surgical procedure which has been shown to reduce the incidence of sexually transmitted infections including HIV, syphilis and HSV-2 [181]. Two systematic reviews and meta-analyses, showed an inverse association between male circumcision and genital HPV prevalence in men [165,167]. It has been suggested that male circumcision could be considered as an additional one-time preventative intervention likely to reduce the burden of HPV-related diseases in both men and women, particularly among those countries in which HPV vaccination programs and cervical screening are not available [167].

- Therapeutic vaccination

Three different vaccines against HPV have been licensed to date, but routine vaccination of males is currently implemented in only a few countries including Australia, Canada, the USA and Austria. The aim of male vaccination is to reduce the rate of anal and penile cancers as well as head and neck cancers [154,182]. A systematic review including a total of 5,294 patients reported vaccine efficacy against persisting (at least six months) anogenital HPV16 infections of 46.9% (28.6-60.8%) and against persisting oral infections of 88% (2–98%). A vaccine efficacy of 61.9% (21.4–82.8%) and 46.8% (20-77.9%) was observed against anal intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 and 3 lesions, respectively [154]. The systematic review reported no meaningful estimates on vaccine efficacy against penile intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or 3, and no data were identified for anal, penile or head and neck squamous cell cancers [154]. A phase 3 clinical trial including 180 male patients evaluated the potential of MVA E2 recombinant vaccinia virus to treat intraepithelial lesions associated with papillomavirus infection [183]. The study showed promising results in terms of immune system stimulation against HPV lesions as well as regression in intraepithelial lesions.

- Prophylactic vaccination

A systematic review and meta-analysis reported that vaccination is moderately effective against genital HPV related diseases irrespective of an individual’s HPV status; however, higher vaccine efficacy was observed in HPV-naïve males [154]. Supporting the early vaccination of boys with the goal of establishing optimal vaccine induced protection before the onset of sexual activity [154]. An RCT including 1,124 patients demonstrated high efficacy of the quadrivalent HPV vaccine vs. placebo against HPV6/11/16/18-related persistent infections [184]. Furthermore, the vaccine elicited a robust immune response and was well tolerated with mild vaccination-related adverse events e.g. injection-site pain and swelling [184]. In addition, a Cochrane review, demonstrated that the quadrivalent HPV vaccine appears to be effective in the prevention of external genital lesions and genital warts in males [185]. Despite the fact quadrivalent HPV vaccines were approved for use in young adult males in 2010 vaccination rates have remained low at 10-15% [186]. Barriers to uptake in this patient group include lack of awareness about HPV vaccines and HPV-related diseases, concerns about vaccine safety and efficacy, economic/cost issues related to vaccine uptake, underestimation of HPV infection risks and sexual activity [186]. Healthcare professionals should provide easily understood and accessible communication resources regarding these issues, in order to educate young adult males and their families on the importance of HPV vaccination to reduce the incidence of certain cancers in later life [186,187].

Figure 2: Diagnostic and treatment algorithm for the management of HPV in men

REFERENCES:

- Bone, R.C., et al. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. Chest, 1992. 101: 1644. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1303622/

- Levy, M.M., et al. 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis Definitions Conference. Crit Care Med, 2003. 31: 1250. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12682500/

- Singer, M., et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA, 2016. 315: 801. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26903338/

- Dellinger, R.P., et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock, 2012. Intensive Care Med, 2013. 39: 165. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23361625/

- Martin, G.S., et al. The epidemiology of sepsis in the United States from 1979 through 2000. N Engl J Med, 2003. 348: 1546. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12700374/

- Hotchkiss, R.S., et al. The pathophysiology and treatment of sepsis. N Engl J Med, 2003. 348: 138. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12519925/

- Rosser, C.J., et al. Urinary tract infections in the critically ill patient with a urinary catheter. Am J Surg, 1999. 177: 287. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10326844/

- Brun-Buisson, C., et al. EPISEPSIS: a reappraisal of the epidemiology and outcome of severe sepsis in French intensive care units. Intensive Care Med, 2004. 30: 580. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14997295/

- Cek, M., et al. Healthcare-associated urinary tract infections in hospitalized urological patients–a global perspective: results from the GPIU studies 2003-2010. World J Urol, 2014. 32: 1587. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24452449/

- Tandogdu, Z., et al. Antimicrobial resistance in urosepsis: outcomes from the multinational, multicenter global prevalence of infections in urology (GPIU) study 2003-2013. World J Urol, 2016. 34: 1193. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26658886/

- Wilson, M.L., et al. Principles and rocedures for blood cultures; Approved Guideline. Clin Lab Stand Inst, 2007. https://clsi.org/media/1448/m47a_sample.pdf

- Howell, M.D., et al. Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock. JAMA, 2017. 317: 847. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28114603/

- Brunkhorst, F.M., et al. Procalcitonin for early diagnosis and differentiation of SIRS, sepsis, severe sepsis, and septic shock. Intensive Care Med, 2000. 26 Suppl 2: S148. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18470710/

- Angeletti, S., et al. Procalcitonin, MR-Proadrenomedullin, and Cytokines Measurement in Sepsis Diagnosis: Advantages from Test Combination. Dis Markers, 2015. 2015: 951532. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26635427/

- Harbarth, S., et al. Diagnostic value of procalcitonin, interleukin-6, and interleukin-8 in critically ill patients admitted with suspected sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2001. 164: 396. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11500339/

- Mikkelsen, M.E., et al. Serum lactate is associated with mortality in severe sepsis independent of organ failure and shock. Crit Care Med, 2009. 37: 1670. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19325467/

- Carlet, J., et al. Guideliness for prevention of nosocomial infections in intensive care unit. Arnette Ed Paris 1994: 41. [No abstract available].

- Riedl, C.R., et al. Bacterial colonization of ureteral stents. Eur Urol, 1999. 36: 53. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10364656/

- DeGroot-Kosolcharoen, J., et al. Evaluation of a urinary catheter with a preconnected closed drainage bag. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol, 1988. 9: 72. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3343502/

- Rivers, E., et al. Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med, 2001. 345: 1368. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11794169/

- Mouncey, P.R., et al. Trial of early, goal-directed resuscitation for septic shock. N Engl J Med, 2015. 372: 1301. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25776532/

- Investigators, A., et al. Goal-directed resuscitation for patients with early septic shock. N Engl J Med, 2014. 371: 1496. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25272316/

- Pro, C.I., et al. A randomized trial of protocol-based care for early septic shock. N Engl J Med, 2014. 370: 1683. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24635773/

- Investigators, P., et al. Early, Goal-Directed Therapy for Septic Shock – A Patient-Level Meta-Analysis. N Engl J Med, 2017. 376: 2223. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28320242/

- Monnet, X., et al. Prediction of fluid responsiveness: an update. Ann Intensive Care, 2016. 6: 111. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27858374/

- Dellinger, R.P., et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care Med, 2004. 32: 858. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15090974/

- Zhang, N., et al. Are Ureaplasma spp. a cause of nongonococcal urethritis? A systematic review and metaanalysis. PLoS ONE, 2014. 9: e113771. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25463970/

- Horner, P.J., et al. 2016 European guideline on the management of non-gonococcal urethritis. Int J STD AIDS, 2016. 27: 928. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27147267/

- Workowski, K.A., et al. Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines, 2015. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015. 64: 1. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr6403a1.htm

- Sarier, M., et al. Microscopy of Gram-stained urethral smear in the diagnosis of urethritis: Which threshold value should be selected? Andrologia, 2018. 50: e13143. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30238498/

- Berntsson, M., et al. Viral and bacterial aetiologies of male urethritis: findings of a high prevalence of EpsteinBarr virus. Int J STD AIDS, 2010. 21: 191. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20215624/

- Couldwell, D.L., et al. Ureaplasma urealyticum is significantly associated with non-gonococcal urethritis in heterosexual Sydney men. Int J STD AIDS, 2010. 21: 337. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20498103/

- Rietmeijer, C.A., et al. Recalibrating the Gram stain diagnosis of male urethritis in the era of nucleic acid amplification testing. Sex Transm Dis, 2012. 39: 18. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22183839/

- Moi, H., et al. Microscopy of Stained Urethral Smear in Male Urethritis; Which Cutoff Should be Used? Sex Trans Dis, 2017. 44: 189. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28178118/

- Mensforth, S., et al. Auditing the use and assessing the clinical utility of microscopy as a point-of-care test for Neisseria gonorrhoeae in a Sexual Health clinic. Int J STD AIDS, 2018. 29: 157. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28705094/

- Atkinson, L.M., et al. ‘The waiting game’: are current chlamydia and gonorrhoea near-patient/point-of-care tests acceptable to service users and will they impact on treatment? Int J STD AIDS, 2016. 27: 650. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26092579/

- Harding-Esch, E.M., et al. Impact of deploying multiple point-of-care tests with a sample first’ approach on a sexual health clinical care pathway. A service evaluation. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 2017. 93: 424. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28159916/

- Jensen, J.S., et al. 2016 European guideline on Mycoplasma genitalium infections. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol, 2016. 30: 1650. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27505296/

- Miller, J.M., et al. A Guide to Utilization of the Microbiology Laboratory for Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases: 2018 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Society for Microbiology. Clin Infect Dis, 2018. 67: e1. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29955859/

- Centers for Disease, C., et al. Recommendations for the laboratory-based detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae–2014. MMWR Recomm Rep, 2014. 63: 1. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24622331/

- Sena, A.C., et al. Persistent and recurrent Trichomonas vaginalis infections: Epidemiology, treatment and management considerations. Exp Rev Anti-Infect Ther, 2014. 12: 673. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24555561/

- Falk, L., et al. Time to eradication of Mycoplasma genitalium after antibiotic treatment in men and women. J Antimicrob Chemother, 2015. 70: 3134. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26283670/

- Ong, J.J., et al. Should female partners of men with non-gonococcal urethritis, negative for Chlamydia trachomatis and Mycoplasma genitalium, be informed and treated? Clinical outcomes from a partner study of heterosexual men with NGU. Sex Trans Dis, 2017. 44: 126. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28079749/

- Bartoletti, R., et al. Management of Urethritis: Is It Still the Time for Empirical Antibiotic Treatments? Eur Urol Focus, 2019. 5: 29. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30318465/

- Moran, J.S., et al. Drugs of choice for the treatment of uncomplicated gonococcal infections. Clin Infect Dis, 1995. 20 Suppl 1: S47. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7795109/

- Kirkcaldy, R.D., et al. The efficacy and safety of gentamicin plus azithromycin and gemifloxacin plus azithromycin as treatment of uncomplicated gonorrhea. Clin Infect Dis, 2014. 59: 1083. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25031289/

- Hathorn, E., et al. The effectiveness of gentamicin in the treatment of Neisseria gonorrhoeae: A systematic review. Syst Rev, 2014. 3: 104. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25239090/

- Soda, M., et al. Evaluation of the microbiological efficacy of a single 2-gram dose of extended-release azithromycin by population pharmacokinetics and simulation in Japanese patients with gonococcal urethritis. Antimicrobial Agents Chemother, 2018. 62: e01409. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29038284/

- Takahashi, S., et al. Clinical efficacy of a single two Gram dose of azithromycin extended release for male patients with urethritis. Antibiotics, 2014. 3: 109. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27025738/

- Yasuda, M., et al. A single 2 g oral dose of extended-release azithromycin for treatment of gonococcal urethritis. J Antimicrob Chemother, 2014. 69: 3116. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24948703/

- Kojima, M., et al. Single-dose treatment of male patients with gonococcal urethritis using 2g spectinomycin: microbiological and clinical evaluations. Int J Antimicrob Agents, 2008. 32: 50. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18539003/

- Shigemura, K., et al. History and epidemiology of antibiotic susceptibilities of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Current Drug Targets, 2015. 16: 272. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25410409/

- Kirkcaldy, R.D., et al. Neisseria gonorrhoeae Antimicrobial Susceptibility Surveillance – The Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project, 27 Sites, United States, 2014. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. Surveillance summaries (Washington, D.C. : 2002), 2016. 65: 1. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27414503/

- Kirkcaldy, R.D., et al. Neisseria gonorrhoeae Antimicrobial Susceptibility Surveillance – The Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project, 27 Sites, United States, 2014. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. Surveillance summaries (Washington, D.C. : 2002), 2016. 65: 1. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27414503/

- Unemo, M., et al. Antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the 21st century: past, evolution, and future. Clin Microbiol Rev, 2014. 27: 587. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24982323/

- Lau, A., et al. The efficacy of azithromycin for the treatment of genital mycoplasma genitalium: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis, 2015. 61: 1389. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26240201/

- Salado-Rasmussen, K., et al. Mycoplasma genitalium testing pattern and macrolide resistance: A Danish nationwide retrospective survey. Clin Infect Dis, 2014. 59: 24. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24729494/

- Read, T.R.H., et al. Azithromycin 1.5g over 5 days compared to 1g single dose in urethral mycoplasma genitalium: Impact on treatment outcome and resistance. Clin Infect Dis, 2017. 64: 250. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28011607/

- Manhart, L.E., et al. Efficacy of Antimicrobial Therapy for Mycoplasma genitalium Infections. Clin Infect Dis, 2015. 61: S802. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26602619/

- Read, T.R.H., et al. Use of pristinamycin for Macrolide-Resistant mycoplasma genitalium infection. Emerging Infect Dis, 2018. 24: 328. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29350154/

- Bissessor, M., et al. Macrolide resistance and azithromycin failure in a Mycoplasma genitalium-infected cohort and response of azithromycin failures to alternative antibiotic regimens. Clin Infect Dis, 2015. 60: 1228. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25537875/

- Lau, C.Y., et al. Azithromycin versus doxycycline for genital chlamydial infections: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Sex Transm Dis, 2002. 29: 497. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12218839/

- Paez-Canro, C., et al. Antibiotics for treating urogenital Chlamydia trachomatis infection in men and nonpregnant women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2019. 2019: CD010871. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30682211/

- Lanjouw, E., et al. 2015 European guideline on the management of Chlamydia trachomatis infections. Int J STD AIDS, 2016. 27: 333. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26608577/

- Khosropour, C.M., et al. Efficacy of standard therapies against Ureaplasma species and persistence among men with nongonococcal urethritis enrolled in a randomised controlled trial. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 2015. 91: 308. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25616607/

- Wagenlehner, F.M.E., et al. The Presentation, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Sexually Transmitted Infections. Deutsches Arzteblatt Int, 2016. 113: 11. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26931526/

- Alexander, R.B., et al. Elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines in the semen of patients with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Urology, 1998. 52: 744. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9801092/

- Alexander, R.B., et al. Chronic prostatitis: results of an Internet survey. Urology, 1996. 48: 568. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8886062/

- Zermann, D.H., et al. Neurourological insights into the etiology of genitourinary pain in men. J Urol, 1999. 161: 903. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10022711/

- Perletti, G., et al. Antimicrobial therapy for chronic bacterial prostatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2013: CD009071. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23934982/

- Dadashpour. M, et al. Acute Prostatitis After Transrectal Ultrasound-guided Prostate Biopsy: Comparing Two Different Antibiotic Prophylaxis Regimen. Biomed Pharmacol J, 2016. 9: 593. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov//

- Schaeffer, A.J., et al. Treatment of chronic bacterial prostatitis with levofloxacin and ciprofloxacin lowers serum prostate specific antigen. J Urol, 2005. 174: 161. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15947609/

- Skerk, V., et al. Comparative analysis of azithromycin and ciprofloxacin in the treatment of chronic prostatitis caused by Chlamydia trachomatis. Int J Antimicrob Agents, 2003. 21: 457. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12727080/

- Vickovic, N., et al. Metronidazole 1.5 gram dose for 7 or 14 days in the treatment of patients with chronic prostatitis caused by Trichomonas vaginalis: A randomized study. J Chemother, 2010. 22: 364. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21123162/

- Cai, T., et al. Serenoa repens associated with Urtica dioica (ProstaMEV) and curcumin and quercitin (FlogMEV) extracts are able to improve the efficacy of prulifloxacin in bacterial prostatitis patients: results from a prospective randomised study. Int J Antimicrob Agents, 2009. 33: 549. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19181486/

- Aliaev Iu, G., et al. [Wardenafil in combined treatment of patients with chronic bacterial prostatitis]. Urologiia, 2008: 52. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19256057/

- Lipsky, B.A., et al. Treatment of bacterial prostatitis. Clin Infect Dis, 2010. 50: 1641. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20459324/

- Wise, G.J., et al. Atypical infections of the prostate. Curr Prostate Rep, 2008. 6: 86. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11918-008-0014-2

- Turner, J.A., et al. Validity and responsiveness of the national institutes of health chronic prostatitis symptom index. J Urol, 2003. 169: 580. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12544311/

- Zegarra Montes, L.Z., et al. Semen and urine culture in the diagnosis of chronic bacterial prostatitis. Int Braz J Urol, 2008. 34: 30. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18341719/

- Budia, A., et al. Value of semen culture in the diagnosis of chronic bacterial prostatitis: a simplified method. Scand J Urol Nephrol, 2006. 40: 326. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16916775/

- Skerk, V., et al. The role of unusual pathogens in prostatitis syndrome. Int J Antimicrob Agents, 2004. 24 Suppl 1: S53.

- Mody, L., et al. A targeted infection prevention intervention in nursing home residents with indwelling devices a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Internal Med, 2015. 175: 714. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25775048/

- Schneider, H., et al. The 2001 Giessen Cohort Study on patients with prostatitis syndrome–an evaluation of inflammatory status and search for microorganisms 10 years after a first analysis. Andrologia, 2003. 35: 258. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14535851/

- Naber, K.G., et al., Prostatitits, epididymitis and orchitis, In: Infectious diseases, D. Armstrong & J. Cohen, Editors. 1999, Mosby: London.

- Badalyan, R.R., et al. Chlamydial and ureaplasmal infections in patients with nonbacterial chronic prostatitis. Andrologia, 2003. 35: 263. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14535852/

- Berger, R.E., Epididymitis., In: Sex Trans Dis, K.K. Holmes, P.-A. Mardh, P.F. Sparling & P.J. Wiesner, Editors. 1984, McGraw-Hill: New York.

- Robinson, A.J., et al. Acute epididymitis: why patient and consort must be investigated. Br J Urol, 1990. 66: 642. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2265337/

- Schaeffer, A.J. Prostatitis: US perspective. Int J Antimicrob Agents, 1999. 11: 205. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10394972/

- Krieger, J.N., et al. NIH consensus definition and classification of prostatitis. Jama, 1999. 282: 236. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10422990/

- Workshop Committee of the national institute of diabetes and digestive and kidney diease (NIDDK), Chronic prostatitis workshop. 1995: Bethesda, Maryland.

- Krieger, J.N., et al. Chronic pelvic pains represent the most prominent urogenital symptoms of “chronic prostatitis”. Urology, 1996. 48: 715. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8911515/

- Nickel, J.C. Effective office management of chronic prostatitis. Urol Clin North Am, 1998. 25: 677. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10026774/

- Etienne, M., et al. Performance of the urine leukocyte esterase and nitrite dipstick test for the diagnosis of acute prostatitis. Clin Infect Dis, 2008. 46: 951. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18288905/

- Meares, E.M., et al. Bacteriologic localization patterns in bacterial prostatitis and urethritis. Invest Urol, 1968. 5: 492. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4870505/

- Nickel, J.C., et al. How does the pre-massage and post-massage 2-glass test compare to the Meares-Stamey 4-glass test in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome? J Urol, 2006. 176: 119. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16753385/

- Doble, A., et al. Ultrasonographic findings in prostatitis. Urol Clin North Am, 1989. 16: 763. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2683305/

- Papp, J.R., et al. Recommendations for the Laboratory-Based Detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae — 2014. MMWR Recomm Rep, 2014. 63: 1. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/262047016

- Polascik, T.J., et al. Prostate specific antigen: a decade of discovery–what we have learned and where we are going. J Urol, 1999. 162: 293. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10411025/

- Wagenlehner, F.M., et al. Bacterial prostatitis. World J Urol, 2013. 31: 711. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23519458/

- Gill, B.C., et al. Bacterial prostatitis. Curr Opin Infect Dis, 2016. 29: 86. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26555038/

- Wagenlehner, F.M., et al. Prostatitis: the role of antibiotic treatment. World J Urol, 2003. 21: 105. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12687400/

- Krieger, J.N. Recurrent lower urinary tract infections in men. J New Rem Clin, 1998. 47: 4. [No abstract available].

- Litwin, M.S., et al. The National Institutes of Health chronic prostatitis symptom index: development and validation of a new outcome measure. Chronic Prostatitis Collaborative Research Network. J Urol, 1999. 162: 369. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10411041/

- Wise, G.J., et al. Atypical infections of the prostate. Curr Prostate Rep, 2008. 6: 86. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11918-008-0014-2

- Schaeffer, A.J., et al. Summary consensus statement: diagnosis and management of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Eur Urol 2003. 43: 1. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12521576/

- Bjerklund Johansen, T.E., et al. The role of antibiotics in the treatment of chronic prostatitis: a consensus statement. Eur Urol, 1998. 34: 457. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9831786/

- Cai, T., et al. Clinical and microbiological efficacy of prulifloxacin for the treatment of chronic bacterial prostatitis due to Chlamydia trachomatis infection: results from a prospective, randomized and open-label study. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol, 2010. 32: 39. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20383345/

- Smelov, V., et al. Chlamydia trachomatis survival in the presence of two fluoroquinolones (lomefloxacin versus levofloxacin) in patients with chronic prostatitis syndrome. Andrologia, 2005. 37: 61. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16026425/

- Ohkawa, M., et al. Antimicrobial treatment for chronic prostatitis as a means of defining the role of Ureaplasma urealyticum. Urol Int, 1993. 51: 129. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8249222/

- Jimenez-Cruz, J.F., et al. Treatment of chronic prostatitis: intraprostatic antibiotic injections under echography control. J Urol, 1988. 139: 967. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3283385/

- Mayersak, J.S. Transrectal ultrasonography directed intraprostatic injection of gentamycin-xylocaine in the management of the benign painful prostate syndrome. A report of a 5 year clinical study of 75 patients. Int Surg, 1998. 83: 347. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10096759/

- Hua, L.X., et al. [The diagnosis and treatment of acute prostatitis: report of 35 cases]. Zhonghua Nan Ke Xue, 2005. 11: 897. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16398358/

- Yoon, B.I., et al. Acute bacterial prostatitis: how to prevent and manage chronic infection? J Infect Chemother, 2012. 18: 444. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22215226/

- Ludwig, M., et al. Diagnosis and therapeutic management of 18 patients with prostatic abscess. Urology, 1999. 53: 340. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9933051/

- Chou, Y.H., et al. Prostatic abscess: transrectal color Doppler ultrasonic diagnosis and minimally invasive therapeutic management. Ultrasound Med Biol, 2004. 30: 719. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15219951/

- Çek, M., et al. Acute and Chronic Epididymitis in EAU-EBU Update Series. Eur Urol Suppl 2017. 16: 124. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1569905617300568

- Pilatz, A., et al. Acute epididymitis revisited: impact of molecular diagnostics on etiology and contemporary guideline recommendations. Eur Urol, 2015. 68: 428. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25542628/

- Harnisch, J.P., et al. Aetiology of acute epididymitis. Lancet, 1977. 1: 819. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/67333/

- Fujisawa, M., et al. Risk factors for febrile genito-urinary infection in the catheterized patients by with spinal cord injury-associated chronic neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction evaluated by urodynamic study and cystography: a retrospective study. World J Urol, 2020. 38: 733. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30949801/

- Street, E., et al. The 2016 European guideline on the management of epididymo-orchitis. IUSTI, 2016. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28632112/