Renal Cell Carcinoma

Part 1

Comprehensive Review Article

Prof. Dr. Semir. A. Salim. Al Samarrai

EPIDEMIOLOGY, AETIOLOGY AND PATHOLOGY:

- Epidemiology

Renal cell carcinoma represents around 3% of all cancers, with the highest incidence occurring in Western countries [1,2]. In Europe, and worldwide, the highest incidence rates are found in the Czech Republic and Lithuania [2]. Generally, during the last two decades until recently, there has been an annual increase of about 2% in incidence both worldwide and in Europe leading to approximately 99,200 new RCC cases and 39,100 kidney cancer-related deaths within the European Union in 2018 [1,2]. In Europe, overall mortality rates for RCC increased until the early 1990s, with rates generally stabilising or declining thereafter [3]. There has been a decrease in mortality since the 1980s in Scandinavian countries and since the early 1990s in France, Germany, Austria, the Netherlands, and Italy. However, in some European countries (Croatia, Estonia, Greece, Ireland, Slovakia), mortality rates still show an upward trend [1,2]. Renal cell carcinoma is the most common solid lesion within the kidney and accounts for approximately 90% of all kidney malignancies. It comprises different RCC subtypes with specific histopathological and genetic characteristics [4]. There is a 1.5:1 predominance in men over women with a higher incidence in the older population [2,5].

- Aetiology

Established risk factors include lifestyle factors such as (hazard ratio [HR]: 1.23-1.58), obesity (HR 1.71), BMI (> 35 vs. < 25), and hypertension (HR: 1.70) [2,5]. 50.2% of patients with RCC are current or former smokers. By histology, the proportions of current or former smokers range from 38% in patients with chromophobe carcinoma to 61.9% in those with collecting duct/medullary carcinoma [6]. In a recent systematic review diabetes was also found to be detrimental [7]. Having a first-degree relative with kidney cancer is also associated with an increased risk of RCC. Moderate alcohol consumption appears to have a protective effect for reasons as yet unknown, while any physical activity level also seems to have a small protective effect [2, 7–11]. A number of other factors have been suggested to be associated with higher or lower risk of RCC, including specific dietary habits and occupational exposure to specific carcinogens, but the literature is inconclusive [5]. The most effective prophylaxis is to avoid cigarette smoking and reduce obesity [2,5].

- Histological Diagnosis

diagnosis Strong Renal cell carcinomas comprise a broad spectrum of histopathological entities described in the 2016 World Health Organization (WHO) classification [4]. There are three main RCC types: clear cell (ccRCC), papillary (pRCC type I and II) and chromophobe (chRCC). The RCC type classification has been confirmed by cytogenetic and genetic analyses [4,12]. Histological diagnosis includes, besides RCC type; evaluation of nuclear grade, sarcomatoid features, vascular invasion, tumour necrosis, and invasion of the collecting system and peri-renal fat, pT, or even pN categories. The four-tiered WHO/ISUP (International Society of Urological Pathology) grading system has replaced the Fuhrman grading system [4].

- Clear-cell RCC

Overall, clear-cell RCC (ccRCC) is well circumscribed and a capsule is usually absent. The cut surface is golden-yellow, often with haemorrhage and necrosis. Loss of chromosome 3p and mutation of the von HippelLindau (VHL) gene at chromosome 3p25 are frequently found. The loss of von Hippel-Lindau protein function contributes to tumour initiation, progression, and metastases. The 3p locus harbours at least four additional ccRCC tumour suppressor genes (UTX, JARID1C, SETD2, PBRM1) [12]. In general, ccRCC has a worse prognosis compared to pRCC and chRCC, but this difference disappears after adjustment for stage and grade [13,14].

- Papillary RCC

Papillary RCC is the second most commonly encountered morphotype of RCC. Papillary RCC has traditionally been subdivided into two types [4]. Type I and II pRCC, which were shown to be clinically and biologically distinct; pRCC type I is associated with activating germline mutations of MET and pRCC type II is associated with activation of the NRF2-ARE pathway and at least three subtypes [15]. Type II pRCC presents a heterogenous group of tumours and future substratification is expected, e.g., oncocytic pRCC [4]. A typical histology of pRCC type I (narrow papillae without any binding, and only microcapillaries in papillae) explains its typical clinical signs. Narrow papillae without any binding and a tough pseudocapsule explain the ideal rounded shape (Pascal’s law) and fragility (specimens have a “minced meat” structure). Tumour growth causes necrotisation of papillae, which is a source of hyperosmotic proteins that cause subsequent “growth” of the tumour, fluid inside the tumour, and only a serpiginous, contrast-enhancing margin. Stagnation in the microcapillaries explain the minimal post-contrast attenuation on CT. Papillary RCC type 1 can imitate a pathologically changed cyst (Bosniak IIF or III). The typical signs of pRCC type 1 are as follows: an ochre colour, more frequently exophytic, extrarenal growth, low grade, and low malignant potential; over 75% of these tumours can be treated by NSS surgery. A substantial risk of renal tumour biopsy tract seeding exists (12.5%), probably due to the fragility of the tumour papillae [16]. Papillary RCC type I is more common and generally considered to have a better prognosis than pRCC type II [4, 14, 17].

- Chromophobe RCC

Overall, chRCC is a pale tan, relatively homogenous and tough, well-demarcated mass without a capsule. Chromophobe RCC cannot be graded by the Fuhrman grading system because of its innate nuclear atypia. An alternative grading system has been proposed, but has yet to be validated [4]. Loss of chromosomes Y, 1, 2, 6, 10, 13, 17 and 21 are typical genetic changes [4]. The prognosis is relatively good, with high fiveyear recurrence-free survival (RFS), and ten-year cancer-specific survival (CSS) [18]. The five- and ten-year recurrence-free survival rates were 94.3% and 89.2%, respectively. Recurrent disease developed in 5.7% of patients, and 76.5% presented with distant metastases with 54% of metastatic disease diagnoses involving a single organ, most commonly bone. Recurrence and death after surgically resected chRCC is rare. For completely excised lesions < pT2a without coagulative necrosis or sarcomatoid features, prognosis is excellent [19]. The new WHO/ISUP grading system merges former entity ‘hybrid oncocytic chromophobe tumour’ with chRCC.

- Other renal tumours

Other renal tumours constitute the remaining renal cortical tumours. These include a variety of uncommon, sporadic, and familial carcinomas, some only recently described, as well as a group of unclassified carcinomas. Renal medullary carcinoma

Renal medullary carcinoma (RMC) is a very rare tumour, comprising < 0.5% of all RCCs [20], predominantly diagnosed in young adults (median age 28 years) with sickle haemoglobinopathies (including sickle cell trait). It is mainly centrally located with ill-defined borders. Renal medullary carcinoma is one of the most aggressive RCCs [21, 22] and most patients (~67%) will present with metastatic disease [21, 23]. Even patients who present with seemingly localised disease may develop macrometastases shortly thereafter, often within a few weeks.

- Carcinoma associated with end-stage renal disease; acquired cystic disease-associated RCC

Cystic degenerative changes (acquired cystic kidney disease [ACKD]) and a higher incidence of RCC, are typical features of end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Renal cell carcinomas of native end-stage kidneys are found in approximately 4% of patients. Their lifetime risk of developing RCCs is at least ten times higher than in the general population. Compared with sporadic RCCs, RCCs associated with ESRD are generally multicentric and bilateral, found in younger patients (mostly male), and are less aggressive. Whether the relatively indolent outcome of tumours in ESRD is due to the mode of diagnosis or a specific ACKD-related molecular pathway still has to be determined. Although the histological spectrum of ESRD tumours is similar to that of sporadic RCC; pRCC occur relatively more frequently [24, 25]. A specific subtype of RCC occurring only in end-stage kidneys has been described as Acquired Cystic Disease-associated RCC (ACD-RCC) with indolent clinical behaviour, likely due to early detection in patients with ESRD on periodic follow-up [4, 12, 26].

- Papillary adenoma

These tumours have a papillary or tubular architecture of low nuclear grade and may be up to 15 mm in diameter, or smaller [27], according to the WHO 2016 classification [4].

- Hereditary kidney tumours

Five to eight percent of RCCs are hereditary; to date there are ten hereditary RCC syndromes associated with specific germline mutations, RCC histology, and comorbidities. Hereditary RCC syndromes are often suggested by family history, age of onset and presence of other lesions typical for the respective syndromes. Median age for hereditary RCC is 37 years; 70% of hereditary RCC tumours are found in the lowest decile (46 years old) of all RCC tumours [28]. Hereditary kidney tumours are found in the following entities: VHL syndrome, hereditary pRCC, Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome, hereditary leiomyomatosis and RCC (HLRCC), tuberous sclerosis, germline succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) mutation, non-polyposis colorectal cancer syndrome, hyperparathyroidism-jaw tumour syndrome, phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) hamartoma syndrome (PHTS), constitutional chromosome 3 translocation, familial non-syndromic ccRCC and BAP1 associated RCC [29]. Renal medullary carcinoma can be included because of its association with hereditary haemoglobinopathies [27, 30–32]. Patients with hereditary kidney cancer syndromes may require repeated surgical intervention [33, 34]. In most hereditary RCCs nephron-sparing approaches are recommended. The exceptions are HLRCC and SDH syndromes for which immediate surgical intervention is recommended due to the aggressive nature of this lesion. For other hereditary syndromes such as VHL, surveillance is recommended until the largest tumour reaches 3 cm in diameter, to reduce interventions [34]. Active surveillance (AS) for VHL, SDH and HLRCC should, in individual patients, follow the growth kinetics, size and location of the tumours, rather than apply a standardised follow-up interval. Regular screening for both renal and extra-renal lesions should follow international guidelines for these syndromes. Multidisciplinary and co-ordinated care should be offered, where appropriate [36]. In HLRCC, renal screening in relatives detects early-stage RCCs [37], with HLRCC RCCs appearing to have unique molecular profiles. Although not hereditary, somatic fusion translocations of TFE3 and TFEB may affect 15% of patients with RCC younger than 45 years and 20-45% of children and young adults diagnosed with RCC [38]. A recent phase II trial demonstrated clinical activity of an oral HIF-2α (hypoxia-inducible factor) inhibitor MK-6482 in VHL patients [39].

- Angiomyolipoma

Angiomyolipoma (AML) is a benign mesenchymal tumour, which can occur sporadically or as part of tuberous sclerosis complex [40]. Overall prevalence is 0.44%, with 0.6% in female and 0.3% in male populations. Only 5% of these patients present with multiple AMLs [41]. Angiomyolipoma belongs to a family of so-called PEComas (perivascular epithelioid cell tumours), characterised by the proliferation of perivascular epithelioid cells. Some PEComas can behave aggressively and can even produce distant metastases. Classic AMLs are completely benign [4, 27, 42]. Ultrasound (US), CT, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) often lead to the diagnosis of AMLs due to the presence of adipose tissue; however, in fat-poor AML, diagnostic imaging cannot reliably identify these lesions. Percutaneous biopsy is rarely useful. Renal tumours that cannot be clearly identified as benign during the initial diagnostic work-up should be treated according to the recommendations provided for the treatment of RCC in these Guidelines. In tuberous sclerosis, AML can be found in enlarged lymph nodes (LNs), which does not represent metastatic spread but a multicentric spread of AMLs. In rare cases, an extension of a non-malignant thrombus into the renal vein or inferior vena cava can be found, associated with an angiotrophic-type growth of AML. Epithelioid AML, a very rare variant of AML, consists of at least 80% epithelioid cells [27, 42]. Epithelioid AMLs are potentially malignant with a highly variable proportion of cases with aggressive behaviour [43]. Criteria to predict the biological behaviour in epithelioid AML were proposed by the WHO 2016 [27, 42]. Angiomyolipoma, in general, has a slow and consistent growth rate, and minimal morbidity [44]. In some cases, larger AMLs can cause local pain. The main complication of AMLs is spontaneous bleeding in the retroperitoneum or into the collecting system, which can be life threatening. Bleeding is caused by spontaneous rupture of the tumour. Little is known about the risk factors for bleeding, but it is believed to increase with tumour size and may be related to the angiogenic component of the tumour that includes irregular blood vessels [44]. The major risk factors for bleeding are tumour size, grade of the angiogenic component, and the presence of tuberous sclerosis [45, 46].

- Treatment

Active surveillance is the most appropriate option for most AMLs (48%). In a group of patients on AS, only 11% of AMLs showed growth, and spontaneous bleeding was reported in 2%, resulting in active treatment in 5% of patients [44, 47]. The association between AML size and the risk of bleeding remains unclear and the traditionally used 4-cm cut-off should not per se trigger active treatment [44]. When surgery is indicated, NSS is the preferred option, if technically feasible. Main disadvantages of less invasive selective arterial embolisation (SAE) are more recurrences and a need for secondary treatment (0.85% for surgery vs. 31% for SAE). For thermal ablation only limited data are available, and this option is used less frequently [44]. Active treatment (SAE, surgery or ablation) should be instigated in case of persistent pain, ruptured AML (acute or repeated bleeding) or in case of a very large AML. Specific patient circumstances may influence the choice to offer active treatment; such as patients at high risk of abdominal trauma, females of childbearing age or patients in whom follow-up or access to emergency care may be inadequate. Selective arterial embolisation is an option in case of life-threatening AML bleeding. In patients diagnosed with tuberous sclerosis, size reduction of often bilateral AMLs can be induced by inhibiting the mTOR pathway using everolimus, as demonstrated in RCTs [48, 49]. In a small phase II trial (n = 20), efficacy of everolimus was demonstrated in sporadic AML as well. A 25% or greater reduction in tumour volume at four and six months was demonstrated in 55.6% and 71.4% of patients, respectively. Twenty percent of patients were withdrawn due to toxicities and 40% self-withdrew from the study due to side effects [50].

- Renal oncocytoma

Oncocytoma is a benign tumour representing 3–7% of all solid renal tumours and its incidence increases to 18% when tumours < 4 cm are considered [4, 47]. The diagnostic accuracy of imaging modalities (CT, MRI) in renal oncocytoma is limited and histopathology remains the only reliable diagnostic modality [4, 47]. However, the new imaging technology 99mTc-sestamibi (SestaMIBI, MIBI) SPECT/CT has shown promising initial results for the differentiation between benign and low grade RCC [51]. Standard treatment for renal oncocytoma is similar to that of other renal tumours; surgical excision by partial- or radical nephrectomy (RN) with subsequent histopathological verification. However, due to the inability of modern imaging techniques to differentiate benign from malignant renal masses, there is a renewed interest in renal mass biopsy (RMB) prior to surgical intervention. Accuracy of the biopsy and management of advanced/progressing oncocytomas need to be considered in this context since oncocytic renal neoplasms diagnosed by RMB at histological examination after surgery showed oncocytoma in only 64.6% of cases. The remainder of the tumours were mainly chRCC (18.7% including 6.3% hybrid oncocytic/chromophobe tumours which have now been grouped histologically with chRCC) [4], other RCCs (12.5%), and other benign lesions (4.2%) [52]. The majority of oncocytomas slowly progress in size with an annual growth rate < 14 mm [53–55]. Preliminary data show that AS may be a safe option to manage oncocytoma in appropriately selected patients. Potential triggers to change management of patients on AS are not well defined [56].

- Cystic renal tumours

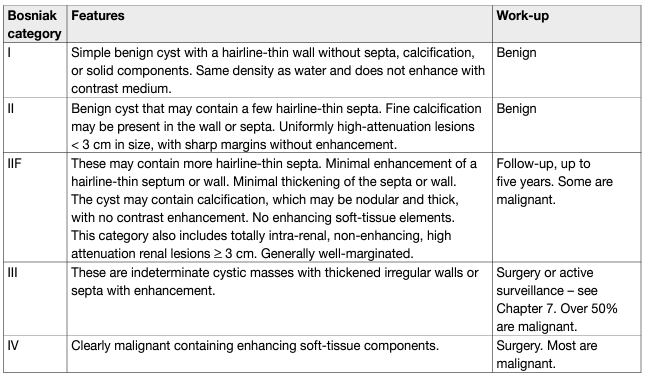

Malignant or benign Treatment or follow-up recommendation based on Bosniak classification. See table 1 Cystic renal lesions are classified according to the Bosniak classification.

Table 1: Bosniak classification of renal cysts

Bosniak I and II cysts are benign lesions which do not require follow-up [57]. Bosniak IV cysts are mostly (83%) malignant tumours [58] with pseudocystic changes only. Bosniak IIF and III cysts remain challenging for clinicians. The differentiation of benign and malignant tumour in categories IIF/III is based on imaging, mostly CT, with an increasing role of MRI and contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS). Computed tomography shows poor sensitivity (36%) and specificity (76%; κ [kappa coefficient] = 0.11) compared with 71% sensitivity and 91% specificity (κ = 0.64) for MRI and 100% sensitivity and 97% specificity for CEUS (κ = 0.95) [59]. Surgical and radiological cohorts pooled estimates show a prevalence of malignancy of 0.51 (0.44–0.58) in Bosniak III and 0.89 (0.83–0.92) in Bosniak IV cysts, respectively. In a systematic review, less than 1% of stable Bosniak IIF cysts showed malignancy during follow-up. Twelve percent of Bosniak IIF cysts had to be reclassified to Bosniak III/IV during radiological follow-up, with 85% of these showing malignancy, which is comparable to the malignancy rates of Bosniak IV cysts [57]. The updated Bosniak classification strengthens the classification and includes also MRI diagnostic criteria [60]. The most common histological type for Bosniak III cysts is ccRCC with pseudocystic changes and low malignant potential [61, 62]; multilocular cystic renal neoplasm of low malignant potential ([MCRNLMP], formerly mcRCC; pRCC type I (very low malignant potential); benign multilocular cyst; benign group of renal epithelial and stromal tumours (REST); and other rare entities. Surgery in Bosniak III cysts will result in over-treatment in 49% of the tumours which are lesions with a low malignant potential. In view of the excellent outcome of these patients in general, a surveillance approach is an alternative to surgical treatment [57, 60, 63, 64].

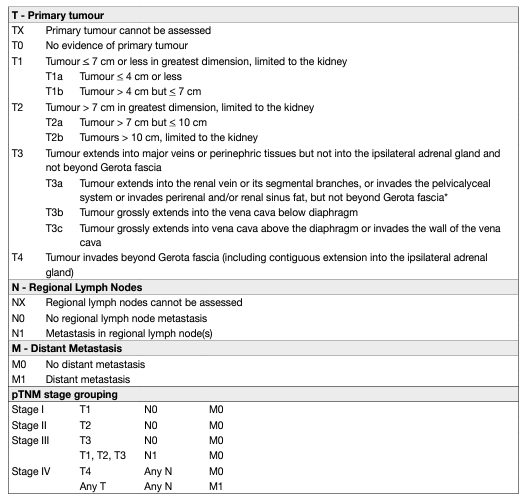

STAGING AND CLASSIFICATION SYSTEMS:

- Staging

The Tumour Node Metastasis (TNM) classification system is recommended for clinical and scientific use [65], but requires continuous re-assessment [4, 66]. A supplement was published in 2012, and the latter’s prognostic value was confirmed in single and multi-institution studies [67, 68]. Tumour size, venous invasion, renal capsular invasion, adrenal involvement, and LN and distant metastasis are included in the TNM classification system (Table 2). However, some uncertainties remain:

• The sub-classification of T1 tumours using a cut-off of 4 cm might not be optimal in NSS for localised cancer.

• The value of size stratification of T2 tumours has been questioned [69].

• Renal sinus fat invasion might carry a worse prognosis than perinephric fat invasion, but, is nevertheless included in the same pT3a stage group [70–73].

• Sub T-stages (pT2b, pT3a, pT3c and pT4) may overlap [68].

• For adequate M staging, accurate pre-operative imaging (chest and abdominal CT) should be performed [74, 75].

Table 2: 2017 TNM classification system

- Anatomic classification systems

Objective anatomic classification systems, such as the Preoperative Aspects and Dimensions Used for an Anatomical (PADUA) classification system, the R.E.N.A.L. nephrometry score, the C-index, an Arterial Based Complexity (ABC) Scoring System and Zonal NePhRO scoring system, have been proposed to standardise the description of renal tumours [76–78]. These systems include assessment of tumour size, exophytic/endophytic properties, proximity to the collecting system and renal sinus, and anterior/posterior or lower/upper pole location. The use of such a system is helpful as it allows objective prediction of potential morbidity of NSS and tumour ablation techniques. These tools provide information for treatment planning, patient counselling, and comparison of partial nephrectomy (PN) and tumour ablation series. However, when selecting the most optimal treatment option, anatomic scores must be considered together with patient features and surgeon experience.

DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION:

- Symptoms

Many renal masses remain asymptomatic until the late disease stages. The majority of RCCs are detected incidentally by non-invasive imaging investigating various non-specific symptoms and other abdominal diseases [79]. In a recent prospective observational cohort study, 60% of patients overall, 87% of patients with stage 1a renal tumours and 36% of patients with stage III or IV disease presented incidentally [80]. The classic triad of flank pain, visible haematuria, and palpable abdominal mass is rare (6–10%) and correlates with aggressive histology, advanced disease and poorer outcomes [80–82]. Paraneoplastic syndromes are found in approximately 30% of patients with symptomatic RCCs [83]. Some symptomatic patients present with symptoms caused by metastatic disease, such as bone pain or persistent cough [84].

- Physical examination

Physical examination has a limited role in RCC diagnosis. However, the following findings should prompt radiological examinations:

• palpable abdominal mass;

• palpable cervical lymphadenopathy;

• non-reducing varicocele and bilateral lower extremity oedema, which suggests venous involvement.

- Laboratory findings

Commonly assessed laboratory parameters are serum creatinine, glomerular filtration rate (GFR), complete cell blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, liver function study, alkaline phosphatase, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), serum corrected calcium [85], coagulation study, and urinalysis. For central renal masses abutting or invading the collecting system, urinary cytology and possibly endoscopic assessment should be considered in order to exclude urothelial cancer. Split renal function should be estimated using renal scintigraphy in the following situations [86, 87]:

• when renal function is compromised, as indicated by increased serum creatinine or significantly decreased GFR;

• when renal function is clinically important; e.g., in patients with a solitary kidney or multiple or bilateral tumours.

Renal scintigraphy is an additional diagnostic option in patients at risk of future renal impairment due to comorbid disorders.

- Imaging investigations

Most renal tumours are diagnosed by abdominal US or CT performed for other medical reasons [79]. Renal masses are classified as solid or cystic based on imaging findings.

- Presence of enhancement

With solid renal masses, the most important criterion for differentiating malignant lesions is the presence of enhancement [88]. Traditionally, US, CT and MRI are used for detecting and characterising renal masses. Most renal masses are diagnosed accurately by imaging alone.

- Computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging

Computed tomography or MRI are used to characterise renal masses. Imaging must be performed unenhanced, in an early arterial phase, and in a parenchymal phase with intravenous contrast material to demonstrate enhancement. In CT imaging, enhancement in renal masses is determined by comparing Hounsfield units (Hus) before, and after, contrast administration. A change of fifteen HU, or more, in the solid tumour parts demonstrates enhancement and thus vital tumour parts [89]. Computed tomography or MRI allows accurate diagnosis of RCC, but cannot reliably distinguish oncocytoma and fat-free AML from malignant renal neoplasms [90–93]. Abdominal CT provides information on [94]:

• function and morphology of the contralateral kidney [95];

• primary tumour extension;

• venous involvement;

• enlargement of locoregional LNs;

• condition of the adrenal glands and other solid organs. Abdominal contrast-enhanced CT angiography is useful in selected cases when detailed information on the renal vascular supply is needed [96, 97]. If the results of CT are indeterminate, CEUS is a valuable alternative to further characterise renal lesions [98, 99-101]. Magnetic resonance imaging may provide additional information on venous involvement if the extent of an inferior vena cava (IVC) tumour thrombus is poorly defined on CT [102-105]. In MRI, especially highresolution T2-weighted images provide a superior delineation of the uppermost tumour thrombus, as the inflow of the enhanced blood may be reduced due to extensive occlusive tumour thrombus growth in the inferior vena cava. The T2-weighted image with its intrinsic contrast allows a good delineation [105]. Magnetic resonance imaging is indicated in patients who are allergic to intravenous CT contrast medium and in pregnancy without renal failure [105, 106]. Magnetic resonance imaging allows the evaluation of a dynamic enhancement without radiation exposure. Advanced MRI techniques such as diffusion-weighted (DWI) and perfusion-weighted imaging are being explored for renal mass assessment [107]. Recently, the use of multiparametric MRI (mpMRI) to diagnose ccRCC via a clear cell likelihood score (ccLS) in small renal masses was reported [108]. The ccLS is a 5-tier classification that denotes the likelihood of a mass representing ccRCC, ranging from ‘very unlikely’ to ‘very likely’. The authors prospectively validated the diagnostic performance of ccLS in 57 patients with cT1a tumours and found a high diagnostic accuracy. The diagnostic performance of mpMRI-based ccLS was further validated in a larger retrospective cohort (n = 434) across all tumour sizes and stages [109], and ccLS was found to be an independent prognostic factor for identifying ccRCC. The system is promising and deserves further validation. For the diagnosis of complex renal cysts (Bosniak IIF-III) MRI may be preferable. The accuracy of CT is limited in these cases, with poor sensitivity (36%) and specificity (76%; κ = 0.11); MRI, due to a higher sensitivity for enhancement, showed a 71% sensitivity and 91% specificity (κ = 0.64). Contrast-enhanced US showed high sensitivity (100%) and specificity (97%), with a negative predictive value of 100% (κ = 0.95) [59]. In younger patients who are worried about the radiation exposure of frequent CT scans, MRI may be offered as alternative although only limited data exist correlating diagnostic radiation exposure to the development of secondary cancers [110]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis [111] compared the diagnostic performance of CEUS vs. contrast-enhanced CT and contrast-enhanced MRI (CEMRI) in the assessment of benign and malignant cystic and solid renal masses. Sixteen studies were included in the pooled analysis. The results suggested comparable diagnostic performance of CEUS compared with CECT (pooled sensitivity 0.96 (95% CI: 0.94-0.98), vs. 0.90 (95% CI: 0.86-0.93), for studies with a final diagnosis of benign or malignant renal masses by pathology), and CEUS vs. CEMRI (pooled sensitivity 0.98 (95% CI: 0.94-1.0), vs. 0.78 (95% CI: 0.66-0.91), for studies with final diagnosis by pathology report or reaffirmed diagnosis by follow-up imaging without pathology report. However, there were significant limitations in the data, including very few studies for CEMRI, clinical and statistical heterogeneity and inconsistency, and high risks of confounding.

- Other investigations

Renal arteriography and inferior venacavography have a limited role in the work-up of selected RCC patients. In patients with any sign of impaired renal function, an isotope renogram and total renal function evaluation should be considered to optimise treatment decision-making [86, 87]. Positron-emission tomography (PET) is not recommended [98, 112].

- Radiographic investigations to evaluate RCC metastases

Chest CT is accurate for chest staging [74, 75, 113-115]. Use of nomograms to calculate risk of lung metastases have been proposed based on tumour size, clinical stage and presence of systemic symptoms [116, 117]. These are based on large, retrospective datasets, and suggest that chest CT may be omitted in patients with cT1a and cN0, and without systemic symptoms, anaemia or thrombocythemia, due to the low incidence of lung metastases (< 1%) in this group of patients. There is a consensus that most bone metastases are symptomatic at diagnosis; thus, routine bone imaging is not generally indicated [113, 118, 119]. However, bone scan, brain CT, or MRI may be used in the presence of specific clinical or laboratory signs and symptoms [118, 120, 121]. A recent prospective comparative blinded study involving 92 consecutive mRCC patients treated with first-line VEGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) (median follow-up 35 months) found that whole-body DWI/MRI detected a statistically significant higher number of bony metastases compared with conventional thoraco-abdomino-pelvic contrast-enhanced CT, with higher number of metastases being an independent prognostic factor for progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) [122]. The incidence of brain metastasis without neurological symptoms was retrospectively evaluated in 1,689 mRCC patients, selected to be included in 68 clinical trials between 2001-2019 [123]. All patients had a mandatory brain screening by CT/MRI. There were 72 patients (4.3%) diagnosed with occult brain metastases, 39% multi-focal. Most patients (61%) were in IMDC intermediate risk, and 26% had a favourable risk. A majority (86%) of the patients had > 2 extracranial metastatic sites, including lung metastases in 92%. After predominantly radiotherapy, performed in 93%, a median patient’s overall survival of 10.3 months (range 7.0–17.9 months) was observed.

- Bosniak classification of renal cystic masses

This system classifies renal cysts into five categories, based on CT imaging appearance, to predict malignancy risk [124, 125], and also advocates treatment for each category (Table 1). A new updated Bosniak classification has been proposed that strengthens the classification and includes MRI diagnostic criteria [60]; however, it requires further validation.

Renal tumour biopsy:

- Indications and rationale

Percutaneous renal tumour biopsy can reveal histology of radiologically indeterminate renal masses and can be considered in patients who are candidates for AS of small masses, to obtain histology before ablative treatments, and to select the most suitable medical and surgical treatment strategy in the setting of metastatic disease [126-131]. A multicentre study assessing 542 surgically removed small renal masses showed that the likelihood of benign findings at pathology is significantly lower in centres where biopsies are performed (5% vs. 16%), suggesting that biopsies can reduce surgery for benign tumours and the potential for short-term and long-term morbidity associated with these procedures [132].

Renal biopsy is not indicated for comorbid and frail patients who can be considered only for conservative management (watchful waiting) regardless of biopsy results. Due to the high diagnostic accuracy of abdominal imaging, renal tumour biopsy is not necessary in patients with a contrast-enhancing renal mass for whom surgery is planned. Core biopsies of cystic renal masses have a lower diagnostic yield and accuracy and are not recommended, unless areas with a solid pattern are present (Bosniak IV cysts) [126, 129, 133]. Histological characterisation by percutaneous biopsy of undefined retroperitoneal masses at imaging may be useful for decision making especially in the younger population.

- Technique

Percutaneous sampling can be performed under local anaesthesia with needle core biopsy and/or fine needle aspiration (FNA). Biopsies can be performed under US or CT guidance, with a similar diagnostic yield [129, 134]. Eighteen-gauge needles are ideal for core biopsies, as they result in low morbidity and provide sufficient tissue for diagnosis [126, 130, 135]. A coaxial technique allowing multiple biopsies through a coaxial cannula should always be used to avoid potential tumour seeding [126, 130]. Core biopsies are preferred for the characterisation of solid renal masses while a combination with FNA can provide complimentary results and improve accuracy for complex cystic lesions [133, 136, 137]. Needle core biopsies were found to have better accuracy for the diagnosis of malignancy compared with FNA [133]. Other studies showed that solid pattern, larger tumour size and exophytic location are predictors of a diagnostic core biopsy [126, 129, 134].

- Diagnostic yield and accuracy

In experienced centres, core biopsies have a high diagnostic yield, specificity, and sensitivity for the diagnosis of malignancy. The above-mentioned meta-analysis showed that sensitivity and specificity of diagnostic core biopsies for the diagnosis of malignancy are 99.1% and 99.7%, respectively [133]. However, 0–22.6% of core biopsies are non-diagnostic (8% in the meta-analysis) [127-131, 134, 135, 138]. If a biopsy is non-diagnostic, and radiologic findings are suspicious for malignancy, a further biopsy or surgical exploration should be considered. Repeat biopsies have been reported to be diagnostic in a high proportion of cases (83-100%) [126, 139-141]. Accuracy of renal tumour biopsies for the diagnosis of tumour histotype is good. The median concordance rate between tumour histotype on renal tumour biopsy and on the surgical specimen of the following PN or RN was 90.3% in the pooled analysis [133]. Assessment of tumour grade on core biopsies is challenging. In the pooled analysis the overall accuracy for nuclear grading was poor (62.5%), but significantly improved (87%) using a simplified two-tier system (high vs. low grade) [133]. The ideal number and location of core biopsies are not defined. However, at least two good quality cores should be obtained and necrotic areas should be avoided to maximise diagnostic yield [126, 129, 142, 143]. Peripheral biopsies are preferable for larger tumours, to avoid areas of central necrosis [144]. In cT2 or greater renal masses, multiple core biopsies taken from at least four separate solid enhancing areas in the tumour were shown to achieve a higher diagnostic yield and a higher accuracy to identify sarcomatoid features, without increasing the complication rate [145].

- Morbidity

Overall, percutaneous biopsies have a low morbidity [133]. Tumour seeding along the needle tract has been regarded as anecdotal in large series and pooled analyses on renal tumour biopsies. Especially the coaxial technique has been regarded as a safe method to avoid any seeding of tumour cells. However, authors recently reported on seven patients in whom tumour seeding was identified on histological examination of the resection specimen after surgical resection of RCC following diagnostic percutaneous biopsy [146]. Six of the seven cases were of the pRCC type. The clinical significance of these findings is still uncertain but only one of these patients developed local tumour recurrence at the site of the previous biopsy [146]. Spontaneously resolving subcapsular/perinephric haematomas are reported in 4.3% of cases in a pooled analysis, but clinically significant bleeding is unusual (0–1.4%; 0.7% in the pooled analysis) and generally self-limiting [133]. Percutaneous biopsy of renal hilar masses is technically feasible with a diagnostic yield similar to that of cortical masses, but with significantly higher post-procedural bleeding compared with cortical masses [147].

- Genetic assessment

Renal cancer can be related to an inherited or de novo monogenic germline alteration and this recognition has significant implications [148]. Hereditary kidney cancer is thought to account for 5–8% of all kidney cancer cases, although this number is likely an underestimation since a more recent study found germline mutations in up to 38% of all metastatic kidney cancer patients [149]. Hereditary kidney tumours). Patients with a germline predisposition to kidney cancer often require multidisciplinary approaches, it is critical for clinicians to be familiar with how and when referral for counselling is warranted, methods of genetic testing, implications of the findings, screening of at-risk (non-renal) organs, and the screening protocol for family members. Well-defined renal cancer management strategies exist, and specific therapeutic strategies are available or in development. Lack of a syndromic manifestation does not exclude a genetic contribution to cancer development. Moreover, other genetic components or polymorphisms are heritable and may confer a mildly increased risk. When several risk alleles are present, they can significantly increase cancer risk. Many factors are associated with an increased risk of hereditary renal cancer syndromes. For instance, even in the absence of clinical manifestations and personal/family history, an age of onset of 46 years or younger should trigger consideration for genetic counselling/germline mutation testing [28]. Moreover, presence of bilateral or multifocal tumours/cysts and/or a first- or second-degree relative with RCC and/or a close blood relative with a known pathogenic variant significantly increases the risk to detect hereditary cancer. The presence of renal cysts can be associated with BHD and VHL, and form part of the clinical diagnostic spectrum. Moreover, specific histologic characteristics can support differential diagnosis of a particular renal cell carcinoma syndrome (e.g., multifocal papillary histology, hereditary leiomyomatosis-associated RCC, RCC with fumarate hydratase deficiency, multiple chromophobe, oncocytoma or oncocytic hybrid, succinate dehydrogenase-deficient RCC histology). Finally, additional tuberous sclerosis complex criteria should be assessed in individuals with AML [28, 150-158].

PROGNOSTIC FACTORS:

- Classification

Prognostic factors can be classified into: anatomical, histological, clinical, and molecular.

- Anatomical factors

Tumour size, venous invasion and extension, collecting system invasion, perinephric- and sinus fat invasion, adrenal involvement, and LN and distant metastasis are included in the TNM classification system [159, 160].

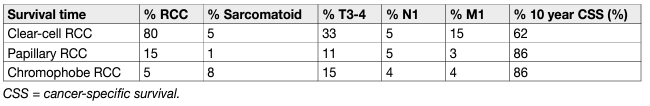

- Histological factors

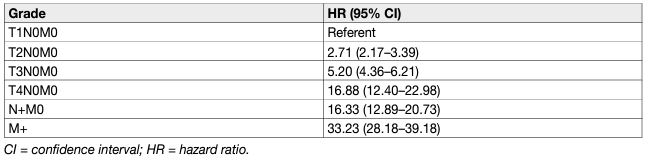

Histological factors include tumour grade, RCC subtype, lymphovascular invasion, tumour necrosis, and invasion of the collecting system [161, 162]. Tumour grade is considered one of the most important histological prognostic factors. Fuhrman nuclear grade is based on simultaneous investigation of nuclear size, nuclear shape and nucleolar prominence [163]. It has been the most widely accepted grading system for several decades, but has now been largely replaced by the WHO/ISUP grading classification [164]. This relies solely on nucleolar prominence for grade 1-3 tumours, allowing for less inter-observer variation [165]. It has been shown that the WHO/ISUP grading provides superior prognostic information compared to Fuhrman grading, especially for grade 2 and grade 3 tumours [166]. Rhabdoid and sarcomatoid changes can be found in all RCC types and are equivalent to grade 4 tumours. Sarcomatoid changes are more often found in chRCC than other subtypes [167]. The percentage of the sarcomatoid component appears to be prognostic as well, with a larger percentage of involvement being associated with worse survival. However, there is no agreement on the optimal prognostic cut-off for sub-classifying sarcomatoid changes [168, 169]. The WHO/ISUP grading system is applicable to both ccRCC and pRCC. It is currently not recommended to grade chRCC. However, a recent study suggested a two-tiered chRCC grading system (low vs. high grade) based on the presence of sarcomatoid differentiation and/or tumour necrosis, which was statistically significant on multivariable analysis [170]. Both the WHO/ISUP and chRCC grading systems need to be validated for prognostic systems and nomograms [164]. Renal cell carcinoma subtype is regarded as another important prognostic factor. On univariable analysis, patients with chRCC vs. pRCC vs. ccRCC had a better prognosis [171, 172] (Table 3). However, prognostic information provided by the RCC type is lost when stratified according to tumour stage [172, 173]. In a recent cohort study of 1,943 patients with ccRCC and pRCC significant survival differences were only shown between pRCC type I and ccRCC [174]. Papillary RCC has been traditionally divided into type 1 and 2, but a subset of tumours shows mixed features. Data also suggest that type 2 pRCC is a heterogeneous entity with multiple molecular subgroups [15]. Some studies suggest poorer survival for type 2 than type 1 [175], but this association is often lost in the multivariable analysis [176]. A meta-analysis did not show a significant survival difference between both types [177, 178]. Renal cell carcinoma with Xp11.2 translocation has a poor prognosis [179]. Its incidence is low, but its presence should be systematically assessed in young patients. Renal cell carcinoma type classification has been confirmed by cytogenetic and genetic analyses [180-182]. Surgically excised malignant complex cystic masses contain ccRCC in the majority of cases, and more than 80% are pT1. In a recent series, five-year CSS was 98% [183]. Differences in tumour stage, grade and CSS between RCC types are illustrated in Table 3.

Table 3: Baseline characteristics and cancer-specific survival of surgically treated patients by RCC type

In all RCC types, prognosis worsens with stage and histopathological grade (Table 4). The five-year OS for all types of RCC is 49%, which has improved since 2006, probably due to an increase in incidentally detected RCCs and new systemic treatments [184, 185]. Although not considered in the current N classification, the number of metastatic regional LNs is an important predictor of survival in patients without distant metastases [186].

Table 4: Cancer-specific survival by stage

- Clinical factors

Clinical factors include performance status (PS), local symptoms, cachexia, anaemia, platelet count, neutrophil count, lymphocyte count, C-reactive protein (CRP) [187], albumin, and various indices deriving from these factors such as the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) [84, 188–193]. As a marker of systemic inflammatory response, a high pre-operative NLR has been associated with poor prognosis [194], but there is significant heterogeneity in the data and no agreement on the optimal prognostic cut-off. Even though obesity is an aetiological factor for RCC, it has also been observed to provide prognostic information. A high body mass index (BMI) appears to be associated with improved survival outcomes in both non-metastatic and metastatic RCC [195–197]. This association is linear with regards to cancer-specific mortality, while obese RCC patients show increasing all-cause mortality with increasing BMI [198]. There is also evolving evidence on the prognostic value of body composition indices measured on cross-sectional imaging, such as sarcopenia and fat accumulation [198, 199, 200].

- Molecular factors

Numerous molecular markers such as carbonic anhydrase IX (CaIX), VEGF, hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF), Ki67 (proliferation), p53, p21 [201], PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog) cell cycle [202], E-cadherin, osteopontin [203] CD44 (cell adhesion) [204, 205], CXCR4 [206], PD-L1 [207], miRNA, SNPs, gene mutations, and gene methylations have been investigated [13]. While the majority of these markers are associated with prognosis and many improve the discrimination of current prognostic models, there has been very little emphasis on external validation studies. Furthermore, there is no conclusive evidence on the value of molecular markers for treatment selection in mRCC [187, 207, 208]. Their routine use in clinical practice is therefore not recommended. Several prognostic and predictive marker signatures have been described for specific systemic treatments in mRCC. In the JAVELIN Renal 101 trial (NCT02684006), a 26-gene immunomodulatory gene signature predicted PFS in those treated with avelumab plus axitinib, while an angiogenesis gene signature was associated with PFS for sunitinib. Mutational profiles and histocompatibility leukocyte antigen (HLA) types were also associated with PFS, while PD-L1 expression and tumour mutational burden were not [209]. In Immotion151 (NCT02420821), a T effector/IFN-γ-high or angiogenesis-low gene expression signature predicted improved PFS for atezolizumab plus bevacizumab compared to sunitinib. The angiogenesis-high gene expression signature correlated with longer PFS in patients treated with sunitinib [210]. In CheckMate 214 (NCT02231749), a higher angiogenesis gene signature score was associated with better overall response rates and PFS for sunitinib, while a lower angiogenesis score was associated with higher ORR in those treated with nivolumab plus ipilimumab. Progression-free survival > 18 months was more often seen in patients with higher expression of Hallmark inflammatory response and Hallmark epithelial mesenchymal transition gene sets [193]. Urinary and plasma Kidney-Injury Molecule-1 (KIM-1) has been identified as a potential diagnostic and prognostic marker. KIM-1 concentrations were found to predict RCC up to five years prior to diagnosis and were associated with a shorter survival time [211]. KIM-1 is a glycoprotein marker of acute proximal tubular injury and therefore mainly expressed in RCC derived from the proximal tubules such as ccRCC and pRCC [212]. While early studies are promising, more high-quality research is required. Several retrospective studies and large molecular screening programs have identified mutated genes and chromosomal changes in ccRCC with distinct clinical outcomes. The expression of the BAP1 and PBRM1 genes, situated on chromosome 3p in a region that is deleted in more than 90% of ccRCCs, have shown to be independent prognostic factors for tumour recurrence [213-215]. These published reports suggest that patients with BAP1-mutant tumours have worse outcomes compared with patients with PBRM1-mutant tumours [214]. Loss of chromosome 9p and 14q have been consistently shown to be associated with poorer survival [216-218]. The TRACERx renal consortium has proposed a genetic classification based on RCC evolution (punctuated vs. branched vs. linear), which correlates with tumour aggressiveness and survival [217]. Additionally, a 16-gene signature was shown to predict disease-free survival (DFS) in patients with non-metastatic RCC [219]. However, these signatures have not been validated by independent researchers yet.

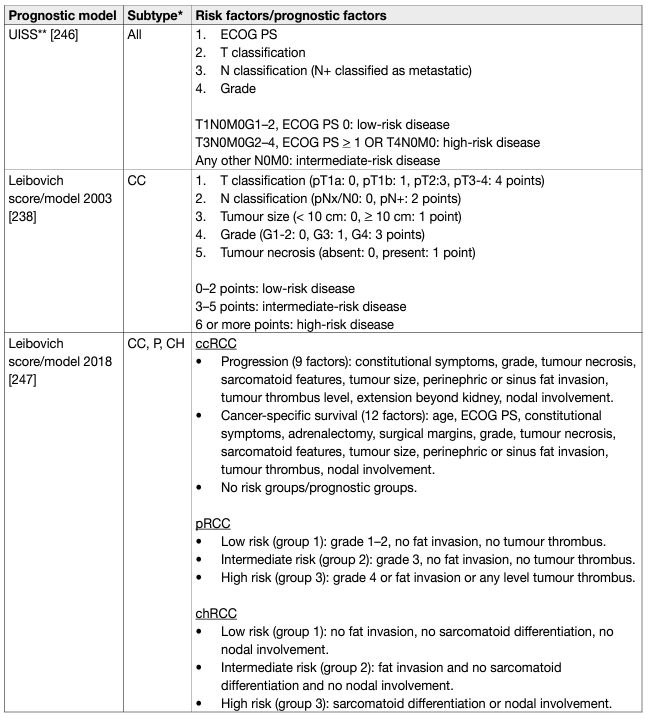

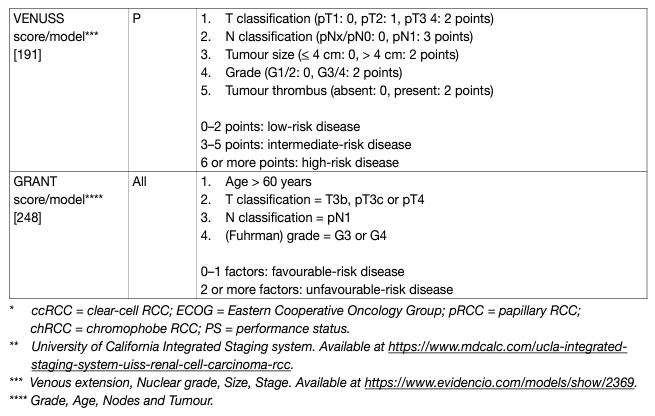

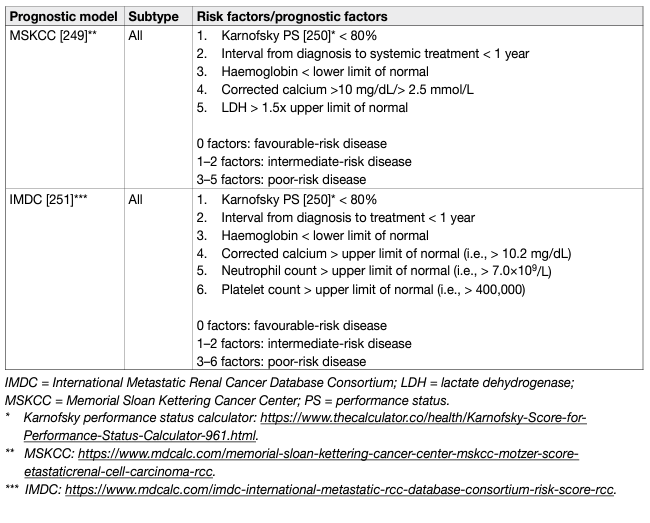

- Prognostic models

Prognostic models combining independent prognostic factors have been developed and externally validated [220-226]. These models are more accurate than TNM stage or grade alone for predicting clinically relevant oncological outcomes. Before being adopted, new prognostic models should be evaluated and compared to current prognostic models with regards to discrimination, calibration and net benefit. In metastatic disease, risk groups assigned by the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) (primarily created in the pre-targeted therapy, and validated in patients receiving targeted therapy) and the International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium (IMDC) (initially created in the targeted therapy era) differ in 23% of cases [227]. The IMDC model has been used in the majority of recent randomised trials, including those with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), and may therefore be the preferred model for clinical practice. The discrimination of the IMDC model may be improved by addition of a seventh variable, namely presence of brain, bone, and/or liver metastases [228]. IMDC intermediate risk disease may also be sub-classified according to presence of bone metastasis or by platelet count [229, 230]. There is no conclusive evidence that one prognostic model is more accurate than another. Tables 5 and 6 summarise the current most relevant prognostic models.

Table 5: Prognostic models for localised RCC

Table 6: Prognostic models for metastatic RCCC

REFERENCES:

- Ferlay, J., et al. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: Estimates for 40 countries and 25 major cancers in 2018. Eur J Cancer, 2018. 103: 356. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30100160/

- Capitanio, U., et al. Epidemiology of Renal Cell Carcinoma. Eur Urol, 2019. 75: 74. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30243799/

- Levi, F., et al. The changing pattern of kidney cancer incidence and mortality in Europe. BJU Int, 2008. 101: 949. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18241251/

- Moch, H., et al. The 2016 WHO Classification of Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs-Part A: Renal, Penile, and Testicular Tumours. Eur Urol, 2016. 70: 93. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26935559/

- Tahbaz, R., et al. Prevention of kidney cancer incidence and recurrence: lifestyle, medication and nutrition. Curr Opin Urol, 2018. 28: 62. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29059103/

- Gansler, T., et al. Prevalence of Cigarette Smoking among Patients with Different Histologic Types of Kidney Cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 2020. 29: 1406. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32357956/

- Al-Bayati, O., et al. Systematic review of modifiable risk factors for kidney cancer. Urol Oncol, 2019. 37: 359. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30685335/

- van de Pol, J.A.A., et al. Etiologic heterogeneity of clear-cell and papillary renal cell carcinoma in the Netherlands Cohort Study. Int J Cancer, 2021. 148: 67. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32638386/

- Jay, R., et al. Alcohol consumption and the risk of renal cancers in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC). Wozniak MB, Brennan P, Brenner DR, Overvad K, Olsen A, Tjønneland A, Boutron-Ruault MC, Clavel-Chapelon F, Fagherazzi G, Katzke V, Kühn T, Boeing H, Bergmann MM, Steffen A, Naska A, Trichopoulou A, Trichopoulos D, Saieva C, Grioni S, Panico S, Tumino R, Vineis P, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Peeters PH, Hjartåker A, Weiderpass E, Arriola L, Molina-Montes E, Duell EJ, Santiuste C, Alonso de la Torre R, Barricarte Gurrea A, Stocks T, Johansson M, Ljungberg B, Wareham N, Khaw KT, Travis RC, Cross AJ, Murphy N, Riboli E, Scelo G.Int J Cancer. 2015 Oct 15;137(8):1953-66. [Epub 2015 Apr 28]. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29559. Urol Oncol, 2017. 35: 117. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28159493/

- Wozniak, M.B., et al. Alcohol consumption and the risk of renal cancers in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition (EPIC). Int J Cancer, 2015. 137: 1953. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25866035/

- Antwi, S.O., et al. Alcohol consumption, variability in alcohol dehydrogenase genes and risk of renal cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer, 2018. 142: 747. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29023769/

- Moch H, et al.WHO Classification of Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs, ed. WHO. 2016, Lyon. [Access date March 2022] https://publications.iarc.fr/Book-And-Report-Series/Who-Classification-Of-Tumours/WHOClassification-Of-Tumours-Of-The-Urinary-System-And-Male-Genital-Organs-2016

- Klatte, T., et al. Prognostic factors and prognostic models for renal cell carcinoma: a literature review. World J Urol, 2018. 36: 1943. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29713755/

- Keegan, K.A., et al. Histopathology of surgically treated renal cell carcinoma: survival differences by subtype and stage. J Urol, 2012. 188: 391. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22698625/

- Linehan, W.M., et al. Comprehensive Molecular Characterization of Papillary Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med, 2016. 374: 135. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26536169/

- Hora, M. Re: Philip S. Macklin, Mark E. Sullivan, Charles R. Tapping, et al. Tumour Seeding in the Tract of Percutaneous Renal Tumour Biopsy: A Report on Seven Cases from a UK Tertiary Referral Centre. Eur Urol 2019;75:861-7. Eur Urol, 2019. 76: e96. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31255420/

- Ledezma, R.A., et al. Clinically localized type 1 and 2 papillary renal cell carcinomas have similar survival outcomes following surgery. World J Urol, 2016. 34: 687. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26407582/

- Volpe, A., et al. Chromophobe renal cell carcinoma (RCC): oncological outcomes and prognostic factors in a large multicentre series. BJU Int, 2012. 110: 76. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22044519/

- Neves, J.B., et al. Pattern, timing and predictors of recurrence after surgical resection of chromophobe renal cell carcinoma. World J Urol, 2021. 39: 3823. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33851271/

- Amin, M.B., et al. Collecting duct carcinoma versus renal medullary carcinoma: an appeal for nosologic and biological clarity. Am J Surg Pathol, 2014. 38: 871. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24805860/

- Shah, A.Y., et al. Management and outcomes of patients with renal medullary carcinoma: a multicentre collaborative study. BJU Int, 2017. 120: 782. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27860149/

- Iacovelli, R., et al. Clinical outcome and prognostic factors in renal medullary carcinoma: A pooled analysis from 18 years of medical literature. Can Urol Assoc J, 2015. 9: E172. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26085875/

- Alvarez, O., et al. Renal medullary carcinoma and sickle cell trait: A systematic review. Pediatr Blood Cancer, 2015. 62: 1694. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26053587/

- Breda, A., et al. Clinical and pathological outcomes of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) in native kidneys of patients with end-stage renal disease: a long-term comparative retrospective study with RCC diagnosed in the general population. World J Urol, 2015. 33: 1. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24504760/

- Breda, A., et al. Erratum to: Clinical and pathological outcomes of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) in native kidneys of patients with end-stage renal disease: a long-term comparative retrospective study with RCC diagnosed in the general population. World J Urol, 2015. 33: 9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24577798/

- Tsuzuki, T., et al. Renal tumors in end-stage renal disease: A comprehensive review. Int J Urol, 2018. 25: 780. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30066367/

- Eble J.N., et al. Pathology and genetics of tumours of the urinary system and male genital organs. In: Pathology and genetics of tumours of the urinary systemand male genital organs. WHO. 2004, IARC: Lyon. https://publications.iarc.fr/Book-And-Report-Series/Who-Classification-Of-Tumours/Pathology-AndGenetics-Of-Tumours-Of-The-Urinary-System-And-Male-Genital-Organs-2004

- Shuch, B., et al. Defining early-onset kidney cancer: implications for germline and somatic mutation testing and clinical management. J Clin Oncol, 2014. 32: 431. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24378414/

- Moch, H., et al. Morphological clues to the appropriate recognition of hereditary renal neoplasms. Semin Diagn Pathol, 2018. 35: 184. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29454577/

- Srigley, J.R., et al. The International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Vancouver Classification of Renal Neoplasia. Am J Surg Pathol, 2013. 37: 1469. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24025519/

- Pignot, G., et al. Survival analysis of 130 patients with papillary renal cell carcinoma: prognostic utility of type 1 and type 2 subclassification. Urology, 2007. 69: 230. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17275070/

- Przybycin, C.G., et al. Hereditary syndromes with associated renal neoplasia: a practical guide to histologic recognition in renal tumor resection specimens. Adv Anat Pathol, 2013. 20: 245. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23752087/

- Shuch, B., et al. The surgical approach to multifocal renal cancers: hereditary syndromes, ipsilateral multifocality, and bilateral tumors. Urol Clin North Am, 2012. 39: 133. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22487757/

- Bratslavsky, G., et al. Salvage partial nephrectomy for hereditary renal cancer: feasibility and outcomes. J Urol, 2008. 179: 67. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17997447/

- Grubb, R.L., 3rd, et al. Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer: a syndrome associated with an aggressive form of inherited renal cancer. J Urol, 2007. 177: 2074. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17509289/

- Nielsen, S.M., et al. Von Hippel-Lindau Disease: Genetics and Role of Genetic Counseling in a Multiple Neoplasia Syndrome. J Clin Oncol, 2016. 34: 2172. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27114602/

- Forde, C., et al. Hereditary Leiomyomatosis and Renal Cell Cancer: Clinical, Molecular, and Screening Features in a Cohort of 185 Affected Individuals. Eur Urol Oncol, 2020. 3: 764. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31831373/

- Kauffman, E.C., et al. Molecular genetics and cellular features of TFE3 and TFEB fusion kidney cancers. Nat Rev Urol, 2014. 11: 465. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25048860/

- Jonasch, E., et al. Phase II study of the oral HIF-2─ inhibitor MK-6482 for Von Hippel-Lindau disease–associated renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol, 2020. 38: 5003. https://ascopubs.org/doi/abs/10.1200/JCO.2020.38.15_suppl.5003

- Bhatt, J.R., et al. Natural History of Renal Angiomyolipoma (AML): Most Patients with Large AMLs >4cm Can Be Offered Active Surveillance as an Initial Management Strategy. Eur Urol, 2016. 70: 85. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26873836/

- Fittschen, A., et al. Prevalence of sporadic renal angiomyolipoma: a retrospective analysis of 61,389 in- and out-patients. Abdom Imaging, 2014. 39: 1009. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24705668/

- Nese, N., et al. Pure epithelioid PEComas (so-called epithelioid angiomyolipoma) of the kidney: A clinicopathologic study of 41 cases: detailed assessment of morphology and risk stratification. Am J Surg Pathol, 2011. 35: 161. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21263237/

- Tsai, H.Y., et al. Clinicopathologic analysis of renal epithelioid angiomyolipoma: Consecutively excised 23 cases. Kaohsiung J Med Sci, 2019. 35: 33. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30844148/

- Fernández-Pello, S., et al. Management of Sporadic Renal Angiomyolipomas: A Systematic Review of Available Evidence to Guide Recommendations from the European Association of Urology Renal Cell Carcinoma Guidelines Panel. Eur Urol Oncol, 2020. 3: 57. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31171501/

- Ramon, J., et al. Renal angiomyolipoma: long-term results following selective arterial embolization. Eur Urol, 2009. 55: 1155. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18440125/

- Nelson, C.P., et al. Contemporary diagnosis and management of renal angiomyolipoma. J Urol, 2002. 168: 1315. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12352384/

- Bhatt, N.R., et al. Dilemmas in diagnosis and natural history of renal oncocytoma and implications for management. Can Urol Assoc J, 2015. 9: E709. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26664505/

- Bissler, J.J., et al. Everolimus for renal angiomyolipoma in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex or sporadic lymphangioleiomyomatosis: extension of a randomized controlled trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant, 2016. 31: 111. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26156073/

- Bissler, J.J., et al. Everolimus long-term use in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex: Four-year update of the EXIST-2 study. PLoS One, 2017. 12: e0180939. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28792952/

- Geynisman, D.M., et al. Sporadic Angiomyolipomas Growth Kinetics While on Everolimus: Results of a Phase II Trial. J Urol, 2020. 204: 531. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32250730/

- Wilson, M.P., et al. Diagnostic accuracy of 99mTc-sestamibi SPECT/CT for detecting renal oncocytomas and other benign renal lesions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Abdom Radiol (NY), 2020. 45: 2532. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32193593/

- Patel, H.D., et al. Surgical histopathology for suspected oncocytoma on renal mass biopsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJU Int, 2017. 119: 661. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28058773/

- Liu, S., et al. Active surveillance is suitable for intermediate term follow-up of renal oncocytoma diagnosed by percutaneous core biopsy. BJU Int, 2016. 118 Suppl 3: 30. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27457972/

- Kawaguchi, S., et al. Most renal oncocytomas appear to grow: observations of tumor kinetics with active surveillance. J Urol, 2011. 186: 1218. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21849182/

- Richard, P.O., et al. Active Surveillance for Renal Neoplasms with Oncocytic Features is Safe. J Urol, 2016. 195: 581. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26388501/

- Abdessater, M., et al. Renal Oncocytoma: An Algorithm for Diagnosis and Management. Urology, 2020. 143: 173. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32512107/

- Schoots, I.G., et al. Bosniak Classification for Complex Renal Cysts Reevaluated: A Systematic Review. J Urol, 2017. 198: 12. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28286071/

- Tse, J.R., et al. Prevalence of Malignancy and Histopathological Association of Bosniak Classification, Version 2019 Class III and IV Cystic Renal Masses. J Urol, 2021. 205: 1031. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33085925/

- Defortescu, G., et al. Diagnostic performance of contrast-enhanced ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging for the assessment of complex renal cysts: A prospective study. Int J Urol, 2017. 24: 184. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28147450/

- Silverman, S.G., et al. Bosniak Classification of Cystic Renal Masses, Version 2019: An Update Proposal and Needs Assessment. Radiology, 2019. 292: 475. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31210616/

- Donin, N.M., et al. Clinicopathologic outcomes of cystic renal cell carcinoma. Clin Genitourin Cancer, 2015. 13: 67. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25088469/

- Park, J.J., et al. Postoperative Outcome of Cystic Renal Cell Carcinoma Defined on Preoperative Imaging: A Retrospective Study. J Urol, 2017. 197: 991. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27765694/

- Chandrasekar, T., et al. Natural History of Complex Renal Cysts: Clinical Evidence Supporting Active Surveillance. J Urol, 2018. 199: 633. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28941915/

- Nouhaud, F.X., et al. Contemporary assessment of the correlation between Bosniak classification and histological characteristics of surgically removed atypical renal cysts (UroCCR-12 study). World J Urol, 2018. 36: 1643. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29730837/

- Sobin LH., et al. TNM classification of malignant tumors, ed. UICC. Vol. 7th edn. 2009. https://www.wiley.com/en-nl/ TNM+Classification+of+Malignant+Tumours%2C+8th+Edition-p-9781119263562

- Gospodarowicz, M.K., et al. The process for continuous improvement of the TNM classification. Cancer, 2004. 100: 1. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14692017/

- Kim, S.P., et al. Independent validation of the 2010 American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM classification for renal cell carcinoma: results from a large, single institution cohort. J Urol, 2011. 185: 2035. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21496854/

- Novara, G., et al. Validation of the 2009 TNM version in a large multi-institutional cohort of patients treated for renal cell carcinoma: are further improvements needed? Eur Urol, 2010. 58: 588. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20674150/

- Waalkes, S., et al. Is there a need to further subclassify pT2 renal cell cancers as implemented by the revised 7th TNM version? Eur Urol, 2011. 59: 258. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21030143/

- Bertini, R., et al. Renal sinus fat invasion in pT3a clear cell renal cell carcinoma affects outcomes of patients without nodal involvement or distant metastases. J Urol, 2009. 181: 2027. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19286201/

- Poon, S.A., et al. Invasion of renal sinus fat is not an independent predictor of survival in pT3a renal cell carcinoma. BJU Int, 2009. 103: 1622. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19154464/

- Bedke, J., et al. Perinephric and renal sinus fat infiltration in pT3a renal cell carcinoma: possible prognostic differences. BJU Int, 2009. 103: 1349. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19076147/

- Izumi, K., et al. Contact with renal sinus is associated with poor prognosis in surgically treated pT1 clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Int J Urol, 2020. 27: 657. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32458519/

- Heidenreich, A., et al. Preoperative imaging in renal cell cancer. World J Urol, 2004. 22: 307. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15290202/

- Sheth, S., et al. Current concepts in the diagnosis and management of renal cell carcinoma: role of multidetector ct and three-dimensional CT. Radiographics, 2001. 21 Spec No: S237. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11598260/

- Klatte, T., et al. A Literature Review of Renal Surgical Anatomy and Surgical Strategies for Partial Nephrectomy. Eur Urol, 2015. 68: 980. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25911061/

- Spaliviero, M., et al. An Arterial Based Complexity (ABC) Scoring System to Assess the Morbidity Profile of Partial Nephrectomy. Eur Urol, 2016. 69: 72. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26298208/

- Hakky, T.S., et al. Zonal NePhRO scoring system: a superior renal tumor complexity classification model. Clin Genitourin Cancer, 2014. 12: e13. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24120084/

- Jayson, M., et al. Increased incidence of serendipitously discovered renal cell carcinoma. Urology, 1998. 51: 203. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9495698/

- Vasudev, N.S., et al. Challenges of early renal cancer detection: symptom patterns and incidental diagnosis rate in a multicentre prospective UK cohort of patients presenting with suspected renal cancer. BMJ Open, 2020. 10: e035938. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32398335/

- Patard, J.J., et al. Correlation between symptom graduation, tumor characteristics and survival in renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol, 2003. 44: 226. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12875943/

- Lee, C.T., et al. Mode of presentation of renal cell carcinoma provides prognostic information. Urol Oncol, 2002. 7: 135. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12474528/

- Sacco, E., et al. Paraneoplastic syndromes in patients with urological malignancies. Urol Int, 2009. 83: 1. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19641351/

- Kim, H.L., et al. Paraneoplastic signs and symptoms of renal cell carcinoma: implications for prognosis. J Urol, 2003. 170: 1742. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14532767/

- Magera, J.S., Jr., et al. Association of abnormal preoperative laboratory values with survival after radical nephrectomy for clinically confined clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Urology, 2008. 71: 278. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18308103/

- Uzzo, R.G., et al. Nephron sparing surgery for renal tumors: indications, techniques and outcomes. J Urol, 2001. 166: 6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11435813/

- Huang, W.C., et al. Chronic kidney disease after nephrectomy in patients with renal cortical tumours: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol, 2006. 7: 735. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16945768/

- Israel, G.M., et al. How I do it: evaluating renal masses. Radiology, 2005. 236: 441. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16040900/

- Israel, G.M., et al. Pitfalls in renal mass evaluation and how to avoid them. Radiographics, 2008. 28: 1325. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18794310/

- Choudhary, S., et al. Renal oncocytoma: CT features cannot reliably distinguish oncocytoma from other renal neoplasms. Clin Radiol, 2009. 64: 517. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19348848/

- Rosenkrantz, A.B., et al. MRI features of renal oncocytoma and chromophobe renal cell carcinoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol, 2010. 195: W421. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21098174/

- Hindman, N., et al. Angiomyolipoma with minimal fat: can it be differentiated from clear cell renal cell carcinoma by using standard MR techniques? Radiology, 2012. 265: 468. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23012463/

- Pedrosa, I., et al. MR imaging of renal masses: correlation with findings at surgery and pathologic analysis. Radiographics, 2008. 28: 985. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18635625/

- Yamashita Y. et al. The therapeutic value of lymph node dissection for renal cell carcinoma. Nishinihon J Urol, 1989: 51: 777. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2021.790381/full

- Gong, I.H., et al. Relationship among total kidney volume, renal function and age. J Urol, 2012. 187: 344. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22099987/

- Ferda, J., et al. Assessment of the kidney tumor vascular supply by two-phase MDCT-angiography. Eur J Radiol, 2007. 62: 295. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17324548/

- Shao, P., et al. Precise segmental renal artery clamping under the guidance of dual-source computed tomography angiography during laparoscopic partial nephrectomy. Eur Urol, 2012. 62: 1001. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22695243/

- Vogel, C., et al. Imaging in Suspected Renal-Cell Carcinoma: Systematic Review. Clin Genitourin Cancer, 2019. 17: e345. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30528378/

- Fan, L., et al. Diagnostic efficacy of contrast-enhanced ultrasonography in solid renal parenchymal lesions with maximum diameters of 5 cm. J Ultrasound Med, 2008. 27: 875. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18499847/

- Correas, J.M., et al. [Guidelines for contrast enhanced ultrasound (CEUS)–update 2008]. J Radiol, 2009. 90: 123. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19212280/

- Mitterberger, M., et al. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound for diagnosis of prostate cancer and kidney lesions. Eur J Radiol, 2007. 64: 231. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17881175/

- Janus, C.L., et al. Comparison of MRI and CT for study of renal and perirenal masses. Crit Rev Diagn Imaging, 1991. 32: 69. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1863349/

- Mueller-Lisse, U.G., et al. Imaging of advanced renal cell carcinoma. World J Urol, 2010. 28: 253. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20458484/

- Kabala, J.E., et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in the staging of renal cell carcinoma. Br J Radiol, 1991. 64: 683. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1884119/

- Hallscheidt, P.J., et al. Preoperative staging of renal cell carcinoma with inferior vena cava thrombus using multidetector CT and MRI: prospective study with histopathological correlation. J Comput Assist Tomogr, 2005. 29: 64. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15665685/

- Putra, L.G., et al. Improved assessment of renal lesions in pregnancy with magnetic resonance imaging. Urology, 2009. 74: 535. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19604560/

- Giannarini, G., et al. Potential and limitations of diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging in kidney, prostate, and bladder cancer including pelvic lymph node staging: a critical analysis of the literature. Eur Urol, 2012. 61: 326. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22000497/

- Johnson, B.A., et al. Diagnostic performance of prospectively assigned clear cell Likelihood scores (ccLS) in small renal masses at multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging. Urol Oncol, 2019. 37: 941. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31540830/

- Steinberg, R.L., et al. Prospective performance of clear cell likelihood scores (ccLS) in renal masses evaluated with multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging. Eur Radiol, 2020. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32770377/

- Capogrosso, P., et al. Follow-up After Treatment for Renal Cell Carcinoma: The Evidence Beyond the Guidelines. Eur Urol Focus, 2016. 1: 272. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28723399/

- Furrer, M.A., et al. Comparison of the Diagnostic Performance of Contrast-enhanced Ultrasound with That of Contrast-enhanced Computed Tomography and Contrast-enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging in the Evaluation of Renal Masses: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Eur Urol Oncol, 2020. 3: 464. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31570270/

- Park, J.W., et al. Significance of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron-emission tomography/computed tomography for the postoperative surveillance of advanced renal cell carcinoma. BJU Int, 2009. 103: 615. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19007371/

- Bechtold, R.E., et al. Imaging approach to staging of renal cell carcinoma. Urol Clin North Am, 1997. 24: 507. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9275976/

- Miles, K.A., et al. CT staging of renal carcinoma: a prospective comparison of three dynamic computed tomography techniques. Eur J Radiol, 1991. 13: 37. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1889427/

- Lim, D.J., et al. Computerized tomography in the preoperative staging for pulmonary metastases in patients with renal cell carcinoma. J Urol, 1993. 150: 1112. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8371366/

- Larcher, A., et al. When to perform preoperative chest computed tomography for renal cancer staging. BJU Int, 2017. 120: 490. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27684653/

- Voss, J., et al. Chest computed tomography for staging renal tumours: validation and simplification of a risk prediction model from a large contemporary retrospective cohort. BJU Int, 2020. 125: 561. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31955483/

- Marshall, M.E., et al. Low incidence of asymptomatic brain metastases in patients with renal cell carcinoma. Urology, 1990. 36: 300. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2219605/

- Koga, S., et al. The diagnostic value of bone scan in patients with renal cell carcinoma. J Urol, 2001. 166: 2126. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11696720/

- Henriksson, C., et al. Skeletal metastases in 102 patients evaluated before surgery for renal cell carcinoma. Scand J Urol Nephrol, 1992. 26: 363. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1292074/

- Seaman, E., et al. Association of radionuclide bone scan and serum alkaline phosphatase in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Urology, 1996. 48: 692. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8911510/

- Beuselinck, B., et al. Whole-body diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging for the detection of bone metastases and their prognostic impact in metastatic renal cell carcinoma patients treated with angiogenesis inhibitors. Acta Oncol, 2020. 59: 818. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32297532/

- Kotecha, R.R., et al. Prognosis of Incidental Brain Metastases in Patients With Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma. J Natl Compr Canc Netw, 2021. 19: 432. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33578374/

- Warren, K.S., et al. The Bosniak classification of renal cystic masses. BJU Int, 2005. 95: 939. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15839908/

- Bosniak, M.A. The use of the Bosniak classification system for renal cysts and cystic tumors. J Urol, 1997. 157: 1852. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9112545/

- Richard, P.O., et al. Renal Tumor Biopsy for Small Renal Masses: A Single-center 13-year Experience. Eur Urol, 2015. 68: 1007. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25900781/

- Shannon, B.A., et al. The value of preoperative needle core biopsy for diagnosing benign lesions among small, incidentally detected renal masses. J Urol, 2008. 180: 1257. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18707712/

- Maturen, K.E., et al. Renal mass core biopsy: accuracy and impact on clinical management. AJR Am J Roentgenol, 2007. 188: 563. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17242269/

- Volpe, A., et al. Contemporary results of percutaneous biopsy of 100 small renal masses: a single center experience. J Urol, 2008. 180: 2333. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18930274/

- Veltri, A., et al. Diagnostic accuracy and clinical impact of imaging-guided needle biopsy of renal masses. Retrospective analysis on 150 cases. Eur Radiol, 2011. 21: 393. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20809129/

- Abel, E.J., et al. Percutaneous biopsy of primary tumor in metastatic renal cell carcinoma to predict high risk pathological features: comparison with nephrectomy assessment. J Urol, 2010. 184: 1877. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20850148/

- Richard, P.O., et al. Is Routine Renal Tumor Biopsy Associated with Lower Rates of Benign Histology following Nephrectomy for Small Renal Masses? J Urol, 2018. 200: 731. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29653161/

- Marconi, L., et al. Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Diagnostic Accuracy of Percutaneous Renal Tumour Biopsy. Eur Urol, 2016. 69: 660. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26323946/

- Leveridge, M.J., et al. Outcomes of small renal mass needle core biopsy, nondiagnostic percutaneous biopsy, and the role of repeat biopsy. Eur Urol, 2011. 60: 578. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21704449/

- Breda, A., et al. Comparison of accuracy of 14-, 18- and 20-G needles in ex-vivo renal mass biopsy: a prospective, blinded study. BJU Int, 2010. 105: 940. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19888984/

- Cate, F., et al. Core Needle Biopsy and Fine Needle Aspiration Alone or in Combination: Diagnostic Accuracy and Impact on Management of Renal Masses. J Urol, 2017. 197: 1396. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28093293/

- Yang, C.S., et al. Percutaneous biopsy of the renal mass: FNA or core needle biopsy? Cancer Cytopathol, 2017. 125: 407. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28334518/

- Motzer, R.J., et al. Phase II randomized trial comparing sequential first-line everolimus and secondline sunitinib versus first-line sunitinib and second-line everolimus in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol, 2014. 32: 2765. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25049330/

- Wood, B.J., et al. Imaging guided biopsy of renal masses: indications, accuracy and impact on clinical management. J Urol, 1999. 161: 1470. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10210375/

- Somani, B.K., et al. Image-guided biopsy-diagnosed renal cell carcinoma: critical appraisal of technique and long-term follow-up. Eur Urol, 2007. 51: 1289. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17081679/

- Vasudevan, A., et al. Incidental renal tumours: the frequency of benign lesions and the role of preoperative core biopsy. BJU Int, 2006. 97: 946. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16643475/