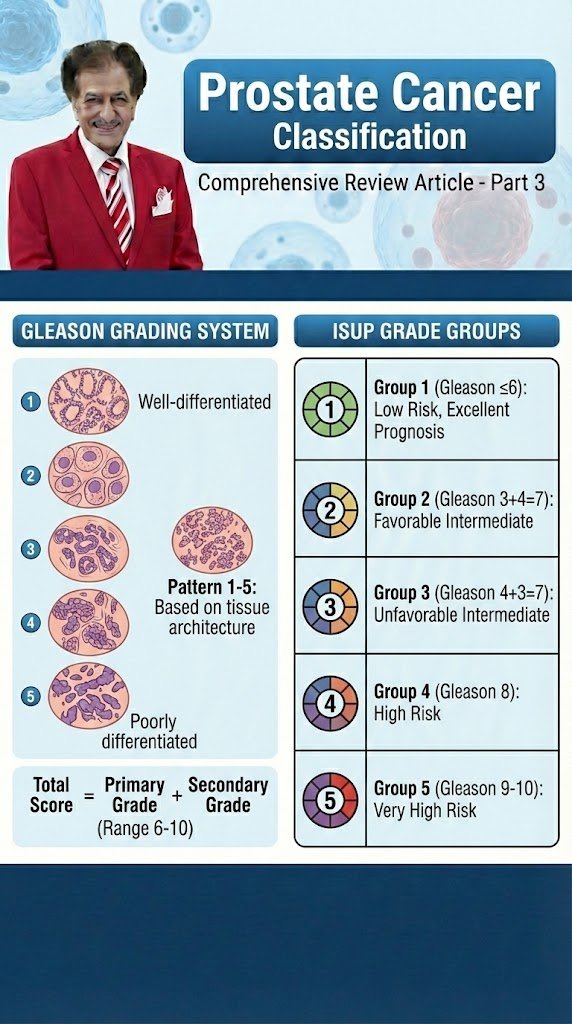

Prostate Cancer

Diagnostic Evaluation

Comprehensive Review Article

Part 3

Prof. Dr. Semir. A. Salim. Al Samarrai

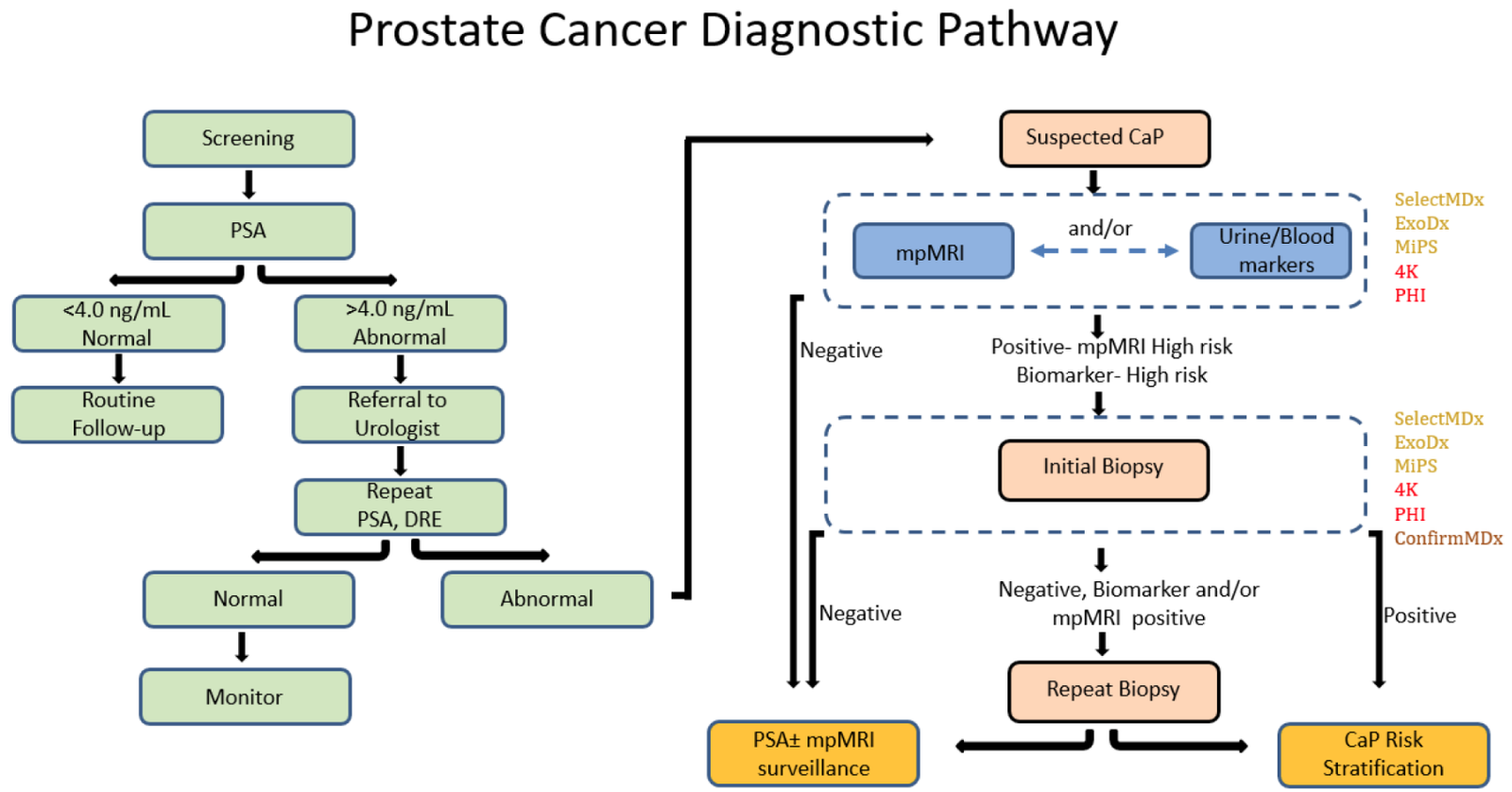

Figure 1. Schematic representation of traditional and proposed mpMRI-molecular-biomarker-directed prostate cancer diagnostic pathway. CaP, prostate cancer; PSA, prostate serum antigen; DRE, digital rectal examination; mpMRI, multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging. Text color of FDA/CLIA-approved molecular markers represents tissue of origin: yellow—urine derived; red—blood derived; brown—tissue derived.

The diagnostic evaluations are a very important measures in the screening and early detection of prostate cancer in decreasing of cancer-specific mortality by developing early and precise treatment and strategy.

Prostate cancer mortality trends range widely from country to country in the industrialised world [1]. Mortality due to PCa has decreased in most Western nations but the magnitude of the reduction varies between countries.

The integration of MRI in the biopsy protocol may reduce the number of men that undergo biopsies while detecting more clinically significant and less clinically insignificant PCa [2,3].

Men at elevated risk of having PCa are those > 50 years [4] or at age > 45 years with a family history of PCa (either paternal or maternal) [5] or of African descent [6,7]. Men of African descent are more likely to be diagnosed with more advanced disease [8] and upgrade was more frequent after prostatectomy as compared to Caucasian men (49% vs. 26%) [9].

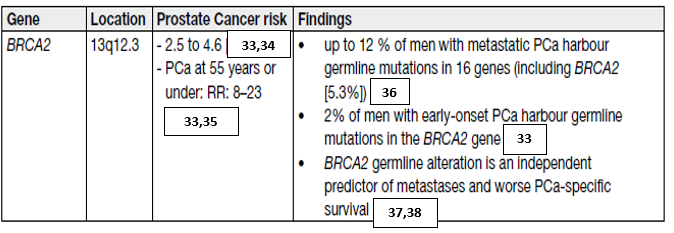

Germline mutations are associated with an increased risk of the development of aggressive PCa, i.e. BRCA2 [10,11]. Prostate-specific antigen screening in male BRCA1 and 2 carriers detected more significant cancers at a younger age compared to non-mutation carriers [12,13].

Men with a baseline PSA < 1 ng/mL at 40 years and < 2 ng/mL at 60 years are at decreased risk of PCa metastasis or death from PCa several decades later [14,15].

Informed men requesting an early diagnosis should be given a PSA test and undergo a DRE [16]. The use of DRE alone in the primary care setting had a sensitivity and specificity below 60%, possibly due to in experience, and can therefore not be recommended to exclude PCa [17].

Prostate-specific antigen measurement and DRE need to be repeated [18]. This could be every 2 years for those initially at risk, or postponed up to 8 years in those not at risk with an initial PSA < 1 ng/mL at 40 years and a PSA < 2 ng/mL at 60 years of age and a negative family history [19].

Risk calculators, combining clinical data (age, DRE findings, PSA level, etc.) may be useful in helping to determine (on an individual basis) what the potential risk of cancer may be, thereby reducing the number of unnecessary biopsies.

Prostate MRI stratifies suspected PCa in lower- and higher risk, based on a 1- to 5- risk scale of having csPCa

[PI-RADS v2.1 guidelines 2019]. A recent meta-analysis of this risk assessment tool showed (on a patient level) a significant cancer detection rate of 9% (5–13%) for PI-RADS 2 scores, 16% (7–27%) for PI-RADS 3 scores, 59% (39–78%) for PI-RADS 4 scores, and 85% (73–94%) for PI-RADS 5 scores [20]. Men with PI-RADS assessment scores of 3 to 5 are recommended to undergo biopsy [21]. Prostate MRI and related MRI-directed biopsies have shown to be at least as diagnostically effective as systematic biopsies alone in diagnosing significant cancers [22]. However, if the MRI-directed biopsy decision strategy (without performing systematic biopsies) can reduce the number of unnecessary biopsy procedures, this will be at the expense of missing a small percentage of csPCas [23].

PSA-density (PSA-D) is the strongest predictor in risk calculators. Combinations of PSA-D and MRI have been explored [24-29], showing guidance in biopsy-decisions whilst safely avoiding redundant biopsy testing.

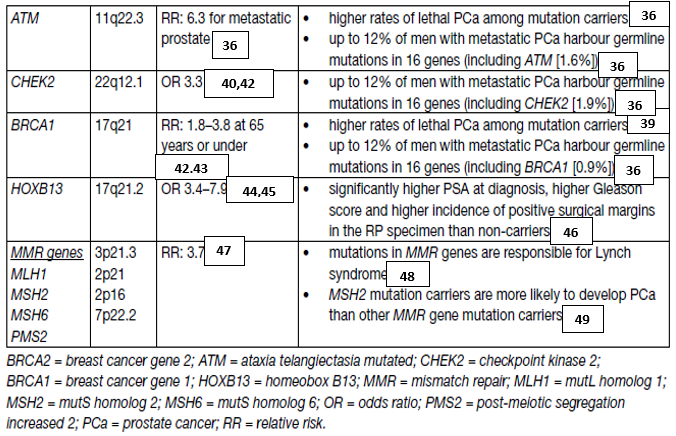

Increasing evidence supports the implementation of genetic counselling and germline testing in early detection and PCa management [30]. Several commercial screening panels are now available to assess main PCa risk genes [31]. However, it remains unclear when germline testing should be considered and how this may impact localised and metastatic disease management. Germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations occur in approximately 0.2% to 0.3% of the general population [32]. It is important to understand the difference between somatic testing, which is performed on the tumour, and germline testing, which is performed on blood or saliva and identifies inherited mutations. Genetic counselling is required prior to and after undergoing germline testing.

Germline mutations can drive the development of aggressive PCa. Therefore, the following men with a personal or family history of PCa or other cancer types arising from DNA repair gene mutations should be considered for germline testing:

• Men with metastatic PCa;

• Men with high-risk PCa and a family member diagnosed with PCa at age < 60 years;

• Men with multiple family members diagnosed with csPCa at age < 60 years or a family member who died from PCa cancer;

• Men with a family history of high-risk germline mutations or a family history of multiple cancers on the same side of the family.

Further research in this field (including not so well-known germline mutations) is needed to develop screening, early detection and treatment paradigms for mutation carriers and family members (table 1).

Table 1. Germline mutations in DNA repair genes associated with increased risk of prostate cancer

By the clinical diagnosis evaluation, prostate cancer is usually suspected on the basis of DRE and/or PSA levels. Definitive diagnosis depends on histopathological verification of adenocarcinoma in prostate biopsy cores.

In ~18% of cases, PCa is detected by suspect DRE alone, irrespective of PSA level [50]. A suspect DRE in patients with a PSA level < 2 ng/mL has a positive predictive value (PPV) of 5–30% [51].

The use of PSA as a serum marker has revolutionised PCa diagnosis [52]. Prostate-specific antigen is organ but not cancer specific; therefore, it may be elevated in benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH), prostatitis and other non-malignant conditions. As an independent variable, PSA is a better predictor of cancer than either

DRE or TRUS [53].

There are no agreed standards defined for measuring PSA [54]. It is a continuous parameter, with higher levels indicating greater likelihood of PCa. Many men may harbour PCa despite having low serum PSA [55].

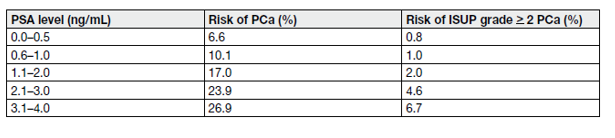

Table 2. Risk of PCa Identified by systemic PCa biopsy in relation to low PSA values

Table 2 demonstrates the occurrence of ISUP > grade 2 PCa in systematic biopsies at low PSA levels, precluding an optimal PSA threshold for detecting non-palpable but csPCa. The use of nomograms and biomarkers may help in predicting indolent PCa [2,57,58]. In case of an elevated PSA (up to 10 ng/mL), a repeated test should considered to confirm the increase before going to the next step.

Prostate-specific antigen density is the level of serum PSA divided by the prostate volume. The higher the PSA-D, the more likely it is that the PCa is clinically significant; in particular, in smaller prostates when a PSA-D cut-off of 0.15 ng/mL/cc was applied [59]. Several studies found a PSA-D over 0.1–0.15 ng/mL/cc predictive of cancer [60,61]. Patients with a PSA-D below 0.09 ng/mL/cc were found unlikely (4%) to be diagnosed with csPCa [62]. A systematic review showed heterogeneity among studies using PSA-D to select men with PI-RADS 3 category on MRI reading for biopsies but suggest a cut-off of 0.15 ng/mL/cc [60].

Various PSA kinetics definitions have been proposed with different methods of calculation (log transformed or not) and eligible PSAs:

• PSA velocity (PSAV): absolute annual increase in serum PSA (ng/mL/year) [63];

• PSA doubling time (PSA-DT): which measures the exponential increase in serum PSA over time [64].

Prostate-specific antigen velocity is more simple to calculate by subtracting the initial value from the final value, dividing by time. However, by ignoring middle values, not all PSA values are accurately taken into account.

Prostate-specific antigen-DT is calculated assuming an exponential rise in serum PSA. The formula takes into account the natural logarithm of 2 divided by the slope obtained from fitting a linear regression of the natural log of PSA over time [65].

However, some rules can be considered for PSA-DT calculation:

• At least 3 PSA measurements are required [65];

• A minimum time period between measurements (4 weeks) is preferable due to potential statistical ‘noise’ when PSA values are obtained too close together (this statement can be reconsidered in case of very active disease);

• All PSA values should be > 0.20 ng/mL and follow a global rising trend;

• All included PSA values should be obtained within the past 12 months at most, to reflect the current disease activity;

• PSA-DT is often mentioned in months, or in weeks in very active disease.

Free/total (f/t) PSA must be used cautiously because it may be adversely affected by several pre-analytical and linical factors (e.g., instability of free PSA at 4°C and room temperature, variable assay characteristics, and concomitant BPH in large prostates) [66]. Prostate cancer was detected in men with a PSA 4–10 ng/mL by biopsy in 56% of men with f/t PSA < 0.10, but in only 8% with f/t PSA > 0.25 ng/mL [67]. A systematic review including 14 studies found a pooled sensitivity of 70% in men with a PSA of 4–10 ng/mL [68]. Free/total PSA is of no clinical use if the total serum PSA is > 10 ng/mL or during follow-up of known PCa. The clinical value of f/t PSA is limited in light of the new diagnostic pathways incorporating MRI.

Several assays measuring a panel of kallikreins in serum or plasma are now commercially available, including the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved Prostate Health Index (PHI) test (combining free and total PSA and the [-2] pro-PSA isoform [p2PSA]), and the four kallikrein (4K) score test (measuring free, intact and total PSA and kallikrein-like peptidase 2 [hK2] in addition to age, DRE and prior biopsy status). Both tests are intended to reduce the number of unnecessary prostate biopsies in PSA-tested men. A few prospective multi-centre studies demonstrated that both the PHI and 4K score test out-performed f/t PSA PCa detection, with an improved prediction of csPCa in men with a PSA between 2–10 ng/mL [69-72]. In a head-to-head comparison both tests performed equally [73].

The probability of detecting malignancy by MRI-identified lesions was standardised first by the use of a 5-grade Likert score [74], and then by the PI-RADS score which has been updated several times since its introduction [75,76].

Consequently, MRI-targeted biopsy without systematic biopsy significantly reduces over-diagnosis of low-risk disease, as compared to systematic biopsy.

Magnetic resonance imaging-targeted biopsies can be used in two different diagnostic pathways: 1) the ‘combined pathway’, in which patients with a positive MRI undergo combined systematic and targeted biopsy, and patients with a negative MRI undergo systematic biopsy; 2) the ‘MRI pathway’, in which patients with a positive MRI undergo only MRI-targeted biopsy, and patients with a negative MRI who are not biopsied at all.

Finally, it must be emphasized that the ‘MR pathway’ has only been evaluated in patients in whom the risk of csPCa was judged high enough to deserve biopsy based on standard clinical assessment including PSA. Magnetic resonance imaging in individuals without any suspicion of PCa is likely to result in an increase in false-positive findings and subsequent unnecessary biopsies.

The need for prostate biopsy is based on PSA level, other biomarkers and/or suspicious DRE and/or imaging. Age, potential co-morbidity and therapeutic consequences should also be considered and discussed beforehand [77]. Risk stratification is a potential tool for reducing unnecessary biopsies [78].

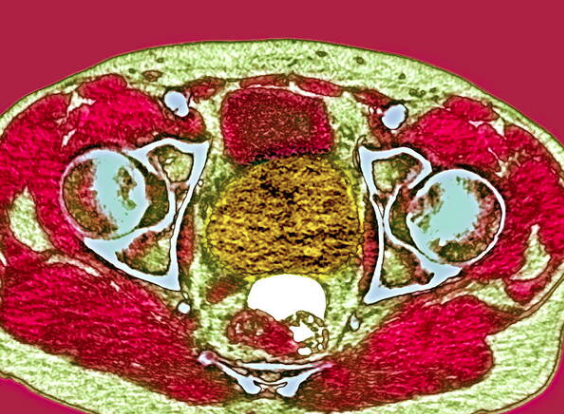

Figure 2. MRI prostate cancer. Axial couloured magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the pelvis of a patient with prostate cancer.

Limited PSA elevation alone should not prompt immediate biopsy. Prostate-specific antigen level should be verified after a few weeks, in the same laboratory using the same assay under standardized conditions (i.e. no ejaculation, manipulations, and urinary tract infections [UTIs]) [79,80]. Empiric use of antibiotics in an asymptomatic patient in order to lower the PSA should not be undertaken [81].

Ultrasound (US)-guided and/or MRI-targeted biopsy is now the SOC. Prostate biopsy is performed by either the transrectal or transperineal approach. Cancer detection rates, when performed without prior imaging with MRI, are comparable between the two approaches [82], however, some evidence suggests reduced infection risk with the transperineal route [83,84]. Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) should not be used as a tool for cancer detection [85].

Men with a previous negative systematic biopsy should be offered a prostate MRI and in case of PIRADS > 3 findings, a repeat (targeted) biopsy has to be done. Other indications for repeat biopsy are:

• Rising and/or persistently elevated PSA;

• Suspicious DRE, 5–30% PCa risk [86,87];

• intraductal carcinoma as a solitary finding, > 90% risk of associated high-grade PCa [88];

The incidence of PCa detected by saturation repeat biopsy (> 20 cores) is 30–43% and depends on the number of cores sampled during earlier biopsies [89]. Saturation biopsy may be performed with the transperineal technique, which detects an additional 38% of PCa. The rate of urinary retention varies substantially from 1.2% to 10% [90-92].

For systematic biopsies, the sample sites should be bilateral from apex to base, as far posterior and lateral as possible in the peripheral gland regardless of the approach used. Sextant biopsy is no longer considered adequate. At least 8 systematic biopsies are recommended in prostates with a size of about 30 cc [44]. Ten to 12 core biopsies are recommended in larger prostates, with > 12 cores not being significantly more conclusive [1,93].

Additional cores should be obtained from suspect areas identified by DRE or on pre-biopsy MRI; multiple (3–5) cores should be taken from each MRI-visible lesion. They can be obtained through cognitive guidance, US/MR fusion software or direct in-bore guidance. Current literature, including systematic reviews and meta-analyses, does not show a clear superiority of one image-guided technique over another [37, 94-95].

To date, no RCT has been published investigating different antibiotic prophylaxis regimens for transperineal prostate biopsy. However, as it is a clean procedure that avoids rectal flora, quinolones or other antibiotics to cover rectal flora may not be necessary. A single dose of cephalosporin only to cover skin commensals has been shown to be sufficient in multiple single cohort series [36,18]. Prior negative mid-stream urine test and routine surgical disinfecting preparation of the perineal skin are mandatory. In one of the largest studies to date, 1,287 patients underwent transperineal biopsy under local anaesthesia only [96]. Antibiotic prophylaxis consisted of a single oral dose of either cefuroxime or cephalexin. Patients with cardiac valve replacements received amoxycillin and gentamicin, and those with severe penicillin allergy received sulphamethoxazole. No quinolones were used. Only one patient developed a UTI with positive urine culture and there was no urosepsis requiring hospitalisation.

Based on a meta-analysis, suggested antimicrobial prophylaxis before transrectal biopsy may consist of:

1. Targeted prophylaxis – based on rectal swab or stool culture.

2. Augmented prophylaxis – two or more different classes of antibiotics (of note: this option is against antibiotic stewardship programmes).

3. Alternative antibiotics:

• fosfomycin trometamol (e.g., 3 g before and 3 g 24–48 hrs. after biopsy);

• Cephalosporin (e.g., ceftriaxone 1 g i.m; cefixime 400 mg p.o for 3 days starting 24 hrs. before biopsy) aminoglycoside (e.g., gentamicin 3 mg/kg i.v.; amikacin 15 mg/kg i.m).

The final diagnosis of PCa is based on histology. The diagnostic criteria include features pathognomonic of cancer, major and minor features favouring cancer and features against cancer. Ancillary staining and additional (deeper) sections should be considered if a suspect lesion is identified [29-31]. Diagnostic uncertainty is resolved by intradepartmental or external consultation [29]. Type and subtype of PCa should be reported such as for instance acinar adenocarcinoma (> 95% of PCa), ductal adenocarcinoma (< 5%) and poorly differentiated small or large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (< 1%), even if representing a small proportion of the PCa. The distinct aggressive nature of ductal adenocarcinoma and small/large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma should be commented upon in the pathology report [27]. Considerable evidence has been accumulated in recent years supporting that among the Gleason grade 4 patterns, the expansile cribriform pattern carries an increased risk of biochemical recurrence, metastatic disease and death of disease [32,97]. Reporting of this sub-pattern based on established criteria) is recommended [98,99]. Intraductal carcinoma, defined as an extension of cancer cells into pre-existing prostatic ducts and acini, distending them, with preservation of basal cells [98], should be distinguished from high-grade PIN [100] as it conveys unfavourable prognosis in terms of biochemical recurrence and cancer-specific survival (CSS) [101,102]. Its presence should be reported, whether occurring in isolation or associated with adenocarcinoma [98].

Each biopsy site should be reported individually, including its location (in accordance with the sampling site) and histopathological findings, which include the histological type and the ISUP 2014 grade [103]. For MRI targeted biopsies consisting of multiple cores per target the aggregated (or composite) ISUP grade and percentage of high-grade carcinoma should be reported per targeted lesion [98]. If the targeted biopsies are negative, presence of specific benign pathology should be mentioned, such as dense inflammation, fibromuscular hyperplasia or granulomatous inflammation [98,104]. A global ISUP grade comprising all systematic (non-targeted) and targeted biopsies is also reported. The global ISUP grade takes into account all biopsies positive for carcinoma, by estimating the total extent of each Gleason grade present.

For instance, if three biopsy sites are entirely composed of Gleason grade 3 and one biopsy site of Gleason grade 4 only, the global ISUP grade would be 2 (i.e. GS 7[3+4]) or 3 (i.e. GS 7 [4+3]), dependent on whether the extent of Gleason grade 3 exceeds that of Gleason grade 4, whereas the worse grade would be ISUP grade 4 (i.e. GS 8[4+4]). Recent publications demonstrated that global ISUP grade is somewhat superior in predicting prostatectomy ISUP grade [105] and BCR [106].

Lymphovascular invasion (LVI) and EPE must each be reported, if identified, since both carry unfavourable prognostic information [107-109].

The proportion of systematic (non-targeted) carcinoma-positive cores as well as the extent of tumour involvement per biopsy core correlate with the ISUP grade, tumour volume, surgical margins and pathologic stage in RP specimens and predict BCR, post-prostatectomy progression and RT failure. These parameters are included in nomograms created to predict pathologic stage and SV invasion after RP and RT failure [110-112]. A pathology report should therefore provide both the proportion of carcinoma-positive cores and the extent of cancer involvement for each core. The length in mm and percentage of carcinoma in the biopsy have equal prognostic impact [50]. An extent of > 50% of adenocarcinoma in a single core is used in some AS protocols as a cut off [51] triggering immediate treatment vs. AS in patients with ISUP grade 1.

A prostate biopsy that does not contain glandular tissue should be reported as diagnostically inadequate.

Mandatory elements to be reported for a carcinoma-positive prostate biopsy are:

• type of carcinoma;

• primary and secondary/worst Gleason grade (per biopsy site and global);

• International Society of Urological Pathology grade (global);

• percentage high-grade carcinoma (global);

• extent of carcinoma (in mm or percentage) (per biopsy site);

• if present: EPE, SV invasion, LVI, intraductal carcinoma/cribriform pattern, peri-neural invasion;

• For MRI-targeted biopsies with multiple cores report aggregate (or composite) ISUP grade and percentage high-grade carcinoma per targeted site;

• For carcinoma-negative MRI-targeted biopsy report specific benign pathology, e.g., fibromuscular hyperplasia or granulomatous inflammation, if present [98].

Histopathological examination of RP specimens describes the pathological stage, histopathological type, grade and surgical margins of PCa. It is recommended that RP specimens are totally embedded to enable

assessment of cancer location, multifocality and heterogeneity. For cost-effectiveness, partial embedding may also be considered, particularly for prostates > 60 g. The most widely accepted method includes complete embedding of the posterior prostate and a single mid-anterior left and right section. Compared with total embedding, partial embedding with this method missed 5% of positive margins and 7% of extraprostatic

extension [113].

The entire RP specimen should be inked upon receipt in the laboratory to demonstrate the surgical margins.

Specimens are fixed by immersion in buffered formalin for at least 24 hours, preferably before slicing. Fixation can be enhanced by injecting formalin which provides more homogeneous fixation and sectioning after 24 hours [114]. After fixation, the apex and the base (bladder neck) are removed and cut into (para)sagittal or radial sections; the shave method is not recommended [115]. The remainder of the specimen is cut in transverse, 3–4 mm sections, perpendicular to the long axis of the urethra. The resultant tissue slices can be embedded and processed as whole-mounts or after quadrant sectioning. Whole-mounts provide better topographic visualisation, faster histopathological examination and better correlation with pre-operative imaging, although they are more time-consuming and require specialist handling. For routine sectioning, the advantages of whole mounts do not outweigh their disadvantages.

Extraprostatic extension is defined as carcinoma mixed with peri-prostatic adipose tissue, or tissue that extends beyond the prostate gland boundaries (e.g., neurovascular bundle, anterior prostate). Microscopic bladder neck invasion is considered EPE. It is useful to report the location and extent of EPE because the latter is related to recurrence risk [52].

There are no internationally accepted definitions of focal or microscopic, vs. non-focal or extensive EPE. Some describe focal as a few glands [53] or < 1 high-power field in one or at most two sections [54]

whereas others measure the depth of extent in millimetres [55].

At the apex of the prostate, tumour mixed with skeletal muscle does not constitute EPE. In the bladder neck, microscopic invasion of smooth muscle fibres is not equated to bladder wall invasion, i.e. not as pT4, because it does not carry independent prognostic significance for PCa recurrence and should be recorded as EPE (pT3a) [57,58]. Stage pT4 is only assigned when the tumour invades the bladder muscle wall as determined macroscopically [116].

The independent prognostic value of PCa volume in RP specimens has not been established [54, 117-60].

Nevertheless, a cut-off of 0.5 mL is traditionally used to distinguish insignificant from clinically relevant cancer [117]. Improvement in prostatic radio-imaging allows more accurate pre-operative measurement of cancer volume. It is recommended that at least the diameter/volume of the dominant tumour nodule should be assessed, or a rough estimate of the percentage of cancer tissue provided [61].

The CT category used in the risk table only refers to the DRE finding. The imaging parameters and biopsy results for local staging are, so far, not part of the risk category stratification [62].

Transrectal US is no more accurate at predicting organ-confined disease than DRE [119]. Some single-centre studies reported good results in local staging using 3D TRUS or colour Doppler but these good results were not confirmed by large-scale studies [63,64].

T2-weighted imaging remains the most useful method for local staging on MRI. Pooled data from a metaanalysis showed a sensitivity and specificity of 0.57 (95% CI: 0.49–0.64) and 0.91 (95% CI: 0.88–0.93), 0.58 (95% CI: 0.47–0.68) and 0.96 (95% CI: 0.95–0.97), and 0.61 (95% CI: 0.54–0.67) and 0.88 (95% CI: 0.85–0.91), for EPE, SVI, and overall stage T3 assessment, respectively [65].

Detection of EPE and SVI seems more accurate at high field strength (3 Tesla) [65], while the added value of functional imaging remains debated [65,66].

Given its low sensitivity for focal (microscopic) EPE, MRI is not recommended for local staging in low-risk patients [120-122]. However, MRI can still be useful for treatment planning.

Abdominal CT and T1-T2-weighted MRI indirectly assess nodal invasion by using LN diameter and morphology. However, the size of non-metastatic LNs varies widely and may overlap the size of LN metastases.

Usually, LNs with a short axis > 8 mm in the pelvis and > 10 mm outside the pelvis are considered malignant. Decreasing these thresholds improves sensitivity but decreases specificity. As a result, the ideal size threshold remains unclear [123,124]. Computed tomography and MRI sensitivity is less than 40% [125,126]. Detection of microscopic LN invasion by CT is < 1% in patients with ISUP grade < 4 cancer, PSA < 20 ng/mL, or localised disease [127-128].

Diffusion-weighted MRI (DW-MRI) may detect metastases in normal-sized nodes, but a negative DW-MRI cannot rule out the presence of LN metastases, and DW-MRI provides only modest improvement for LN staging over conventional imaging [76].

Due of its low sensitivity, choline PET/CT does not reach clinically acceptable diagnostic accuracy for detection of LN metastases, or to rule out a nodal dissection based on risk factors or nomograms.

Prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) positron-emission tomography (PET)/CT uses several different radiopharmaceuticals; most published studies used 68Ga-labelling for PSMA PET imaging, but some used 18F-labelling. At present there are no conclusive data about comparison of such tracers, with additional new radiotracers being developed. Prostate-specific membrane antigen is also an attractive target because of its specificity for prostate tissue, even if the expression in other non-prostatic malignancies or benign conditions may cause incidental false-positive findings [128-132].

Prostate-specific antigen may be a predictor of a positive PSMA PET/CT. In the primary staging cohort from a meta-analysis, however, no robust estimates of positivity were found [133]. The tracer uptake is also influenced by the ISUP grade. Similarly, patients with PSA levels > 10 ng/mL showed significantly higher uptake than those with PSA levels < 10 ng/mL [134].

Comparison between PSMA PET/CT and MRI was performed in a systematic review and meta-analysis including 13 studies (n = 1,597) [33]. 68Ga-PSMA was found to have a higher sensitivity and a comparable specificity for staging pre-operative LN metastases in intermediate- and high-risk PCa. Another prospective trial reported superior sensitivity of PSMA PET/CT as compared to MRI for nodal staging of 36 high-risk PCa patients [34].

PSMA PET/CT has a good sensitivity and specificity for LN involvement, possibly impacting clinical decision-making. In a review and meta-analysis including 37 articles, a subgroup analysis was performed in patients undergoing PSMA PET/CT for primary staging. On a per-patient-based analysis, the sensitivity and specificity of 68Ga-PSMA PET were 77% and 97%, respectively, after eLND at the time of RP. On a per-lesionbased analysis, sensitivity and specificity were 75% and 99%, respectively [133].

In summary, PSMA PET/CT is more appropriate in N-staging as compared to MRI, abdominal contrastenhanced CT or choline PET/CT; however, small LN metastases, under the spatial resolution of PET (~5 mm), may still be missed.

99mTc-Bone scan is a highly sensitive conventional imaging technique, evaluating the distribution of active bone formation in the skeleton related to malignant and benign disease. A meta-analysis showed combined sensitivity and specificity of 79% (95% CI: 73–83%) and 82% (95% CI: 78–85%) at patient level [38]. Bone scan diagnostic yield is significantly influenced by the PSA level, the clinical stage and the tumour ISUP grade [123,40]. A retrospective study investigated the association between age, PSA and GS in 703 newly diagnosed PCa patients who were referred for bone scintigraphy. The incidence of bone metastases increased substantially with rising PSA and upgrading GS [41]. In two studies, a dominant Gleason pattern of 4 was found to be a significant predictor of positive bone scan [42,43]. Bone scanning should be performed in symptomatic patients, independent of PSA level, ISUP grade or clinical stage [123].

It remains unclear whether choline PET/CT is more sensitive than bone scan but it has higher specificity with fewer indeterminate bone lesions [134,135,136]. Choline PET/CT has also the advantage of detecting visceral and nodal metastases.

Diffusion-weighted whole-body and axial skeleton MRI are more sensitive than bone scan and targeted conventional radiography in detecting bone metastases in high-risk PCa. Whole-body MRI can also detect visceral and nodal metastases; it was shown to be more sensitive and specific than combined bone scan, targeted radiography and abdominopelvic CT [137].

The field of non-invasive N- and M-staging of PCa patients is evolving very rapidly. Evidence shows that choline PET/CT, PSMA PET/CT and whole-body MRI provide a more sensitive detection of LN- and bone metastases than the classical work-up with bone scan and abdominopelvic CT. In view of the evidence offered by the randomised, multi-centre proPSMA trial [138], replacing bone scan and abdominopelvic CT by more

sensitive imaging modalities may be a consideration in patients with high-risk PCa undergoing initial staging.

REFERENCES:

1. IARC France All Cancers (excluding non-melanoma skin cancer) Estimated Incidence, Mortality and

Prevalence Worldwide in 2020. [Access date March 2022].

https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/cancers/40-All-cancers-excluding-non-melanoma-skincancer-

fact-sheet.pdf

2. Eklund, M., et al. MRI-Targeted or Standard Biopsy in Prostate Cancer Screening. N Engl J Med,

2021. 385: 908.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34237810/

3. Eldred-Evans, D., et al. Population-Based Prostate Cancer Screening With Magnetic Resonance

Imaging or Ultrasonography: The IP1-PROSTAGRAM Study. JAMA Oncol, 2021. 7: 395.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33570542/

4. Carlsson, S., et al. Screening for Prostate Cancer Starting at Age 50-54 Years. A Population-based

Cohort Study. Eur Urol, 2017. 71: 46.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27084245/

5. Albright, F., et al. Prostate cancer risk prediction based on complete prostate cancer family history.

Prostate, 2015. 75: 390.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25408531/

6. Kamangar, F., et al. Patterns of cancer incidence, mortality, and prevalence across five continents:

defining priorities to reduce cancer disparities in different geographic regions of the world. J Clin

Oncol, 2006. 24: 2137.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16682732/

7. Chornokur, G., et al. Disparities at presentation, diagnosis, treatment, and survival in African

American men, affected by prostate cancer. Prostate, 2011. 71: 985.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21541975/

8. Karami, S., et al. Earlier age at diagnosis: another dimension in cancer disparity? Cancer Detect

Prev, 2007. 31: 29.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17303347/

9. Sanchez-Ortiz, R.F., et al. African-American men with nonpalpable prostate cancer exhibit greater

tumor volume than matched white men. Cancer, 2006. 107: 75.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16736511/

10. Bancroft, E.K., et al. Targeted Prostate Cancer Screening in BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutation Carriers:

Results from the Initial Screening Round of the IMPACT Study. Eur Urol, 2014. 66: 489.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24484606/

11. Gulati, R., et al. Screening Men at Increased Risk for Prostate Cancer Diagnosis: Model Estimates of

Benefits and Harms. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 2017. 26: 222.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27742670/

12. Page, E.C., et al. Interim Results from the IMPACT Study: Evidence for Prostate-specific Antigen

Screening in BRCA2 Mutation Carriers. Eur Urol, 2019. 76: 831.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31537406/

13. Mano, R., et al. Malignant Abnormalities in Male BRCA Mutation Carriers: Results From a

Prospectively Screened Cohort. JAMA Oncol, 2018. 4: 872.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29710070/

14. Vickers, A.J., et al. Strategy for detection of prostate cancer based on relation between prostate

specific antigen at age 40-55 and long term risk of metastasis: case-control study. BMJ, 2013.

346: f2023.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23596126/

15. Carlsson, S., et al. Influence of blood prostate specific antigen levels at age 60 on benefits and

harms of prostate cancer screening: population based cohort study. BMJ, 2014. 348: g2296.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24682399/

16. Loeb, S., et al. Pathological characteristics of prostate cancer detected through prostate specific

antigen based screening. J Urol, 2006. 175: 902.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16469576/

17. Naji, L., et al. Digital Rectal Examination for Prostate Cancer Screening in Primary Care: A

Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann Fam Med, 2018. 16: 149.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29531107/

18. Martin, R.M., et al. Effect of a Low-Intensity PSA-Based Screening Intervention on Prostate Cancer

Mortality: The CAP Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA, 2018. 319: 883.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29509864/

19. Gelfond, J., et al. Intermediate-Term Risk of Prostate Cancer is Directly Related to Baseline Prostate

Specific Antigen: Implications for Reducing the Burden of Prostate Specific Antigen Screening.

J Urol, 2015. 194: 46.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25686543/

20. Oerther, B., et al. Cancer detection rates of the PI-RADSv2.1 assessment categories: systematic

review and meta-analysis on lesion level and patient level. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis, 2021.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34230616/

21. Padhani, A.R., et al. PI-RADS Steering Committee: The PI-RADS Multiparametric MRI and MRIdirected

Biopsy Pathway. Radiology, 2019: 182946.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31184561/

22. Drost, F.H., et al. Prostate MRI, with or without MRI-targeted biopsy, and systematic biopsy for

detecting prostate cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2019. 4: CD012663.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31022301/

23. Schoots, I.G., et al. Analysis of Magnetic Resonance Imaging-directed Biopsy Strategies for

Changing the Paradigm of Prostate Cancer Diagnosis. Eur Urol Oncol, 2020. 3: 32.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31706946/

24. Schoots, I.G., et al. Risk-adapted biopsy decision based on prostate magnetic resonance imaging

and prostate-specific antigen density for enhanced biopsy avoidance in first prostate cancer

diagnostic evaluation. BJU Int, 2021. 127: 175.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33089586/

25. Deniffel, D., et al. Avoiding Unnecessary Biopsy: MRI-based Risk Models versus a PI-RADS and

PSA Density Strategy for Clinically Significant Prostate Cancer. Radiology, 2021: 204112.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34032510/

26. Boesen, L., et al. Prebiopsy Biparametric Magnetic Resonance Imaging Combined with Prostatespecific

Antigen Density in Detecting and Ruling out Gleason 7-10 Prostate Cancer in Biopsy-naive

Men. Eur Urol Oncol, 2019. 2: 311.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31200846/

27. Falagario, U.G., et al. Avoiding Unnecessary Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and Biopsies:

Negative and Positive Predictive Value of MRI According to Prostate-specific Antigen Density,

4Kscore and Risk Calculators. Eur Urol Oncol, 2019. 3: 700.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31548130/

28. Knaapila, J., et al. Prebiopsy IMPROD Biparametric Magnetic Resonance Imaging Combined with

Prostate-Specific Antigen Density in the Diagnosis of Prostate Cancer: An External Validation Study.

Eur Urol Oncol, 2019. 6: 30134.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31501082/

29. Hansen, N.L., et al. Multicentre evaluation of targeted and systematic biopsies using magnetic

resonance and ultrasound image-fusion guided transperineal prostate biopsy in patients with a

previous negative biopsy. BJU Int, 2017. 120: 631.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27862869/

30. Mark, J.R., et al. Genetic Testing Guidelines and Education of Health Care Providers Involved in

Prostate Cancer Care. Urol Clin North Am, 2021. 48: 311.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34210487/

31. Giri, V.N., et al. Implementation of Germline Testing for Prostate Cancer: Philadelphia Prostate

Cancer Consensus Conference 2019. J Clin Oncol, 2020. 38: 2798.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32516092/

32. John, E.M., et al. Prevalence of pathogenic BRCA1 mutation carriers in 5 US racial/ethnic groups.

Jama, 2007. 298: 2869.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18159056/

33. Edwards, S.M., et al. Two percent of men with early-onset prostate cancer harbor germline

mutations in the BRCA2 gene. Am J Hum Genet, 2003. 72: 1.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12474142/

34. van Asperen, C.J., et al. Cancer risks in BRCA2 families: estimates for sites other than breast and

ovary. J Med Genet, 2005. 42: 711.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16141007/

35. Agalliu, I., et al. Rare germline mutations in the BRCA2 gene are associated with early-onset

prostate cancer. Br J Cancer, 2007. 97: 826.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17700570/

36. Pritchard, C.C., et al. Inherited DNA-Repair Gene Mutations in Men with Metastatic Prostate Cancer.

N Engl J Med, 2016. 375: 443.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27433846/

37. Castro, E., et al. Germline BRCA mutations are associated with higher risk of nodal involvement,

distant metastasis, and poor survival outcomes in prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol, 2013. 31: 1748.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23569316/

38. Leongamornlert, D., et al. Frequent germline deleterious mutations in DNA repair genes in familial

prostate cancer cases are associated with advanced disease. Br J Cancer, 2014. 110: 1663.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24556621/

39.Na, R., et al. Germline Mutations in ATM and BRCA1/2 Distinguish Risk for Lethal and Indolent

Prostate Cancer and are Associated with Early Age at Death. Eur Urol, 2017. 71: 740.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27989354/

40. Wang, Y., et al. CHEK2 mutation and risk of prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Int J Clin Exp Med, 2015. 8: 15708.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26629066/

41. Zhen, J.T., et al. Genetic testing for hereditary prostate cancer: Current status and limitations.

Cancer, 2018. 124: 3105.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29669169/

42. Leongamornlert, D., et al. Germline BRCA1 mutations increase prostate cancer risk. Br J Cancer,

2012. 106: 1697.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22516946/

43. Thompson, D., et al. Cancer Incidence in BRCA1 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2002.

94: 1358.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12237281/

44. Ewing, C.M., et al. Germline mutations in HOXB13 and prostate-cancer risk. N Engl J Med, 2012.

366: 141.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22236224/

45. Karlsson, R., et al. A population-based assessment of germline HOXB13 G84E mutation and

prostate cancer risk. Eur Urol, 2014. 65: 169.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22841674/

46. Storebjerg, T.M., et al. Prevalence of the HOXB13 G84E mutation in Danish men undergoing radical

prostatectomy and its correlations with prostate cancer risk and aggressiveness. BJU Int, 2016.

118: 646.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26779768/

47. Ryan, S., et al. Risk of prostate cancer in Lynch syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 2014. 23: 437.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24425144/

48. Carlsson, S., et al. Influence of blood prostate specific antigen levels at age 60 on benefits and

harms of prostate cancer screening: population based cohort study. BMJ, 2014. 348: g2296.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24682399/

49. Rosty, C., et al. High prevalence of mismatch repair deficiency in prostate cancers diagnosed in

mismatch repair gene mutation carriers from the colon cancer family registry. Fam Cancer, 2014.

13: 573.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25117503/

50. Rouviere, O., et al. Use of prostate systematic and targeted biopsy on the basis of multiparametric

MRI in biopsy-naive patients (MRI-FIRST): a prospective, multicentre, paired diagnostic study.

Lancet Oncol, 2019. 20: 100.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30470502/

51. van der Leest, M., et al. Head-to-head Comparison of Transrectal Ultrasound-guided Prostate

Biopsy Versus Multiparametric Prostate Resonance Imaging with Subsequent Magnetic Resonanceguided

Biopsy in Biopsy-naive Men with Elevated Prostate-specific Antigen: A Large Prospective

Multicenter Clinical Study. Eur Urol, 2019. 75: 570.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30477981/

52. Zumsteg, Z.S., et al. Unification of favourable intermediate-, unfavourable intermediate-, and very

high-risk stratification criteria for prostate cancer. BJU Int, 2017. 120: E87.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28464446/

53. IARC France All Cancers (excluding non-melanoma skin cancer) Estimated Incidence, Mortality and

Prevalence Worldwide in 2020. [Access date March 2022].

https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/cancers/40-All-cancers-excluding-non-melanoma-skincancer-

fact-sheet.pdf

54. Etzioni, R., et al. Limitations of basing screening policies on screening trials: The US Preventive

Services Task Force and Prostate Cancer Screening. Med Care, 2013. 51: 295.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23269114/

55. Loeb, S. Guideline of guidelines: prostate cancer screening. BJU Int, 2014. 114: 323.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24981126/

56. Falagario, U.G., et al. Avoiding Unnecessary Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and Biopsies:

Negative and Positive Predictive Value of MRI According to Prostate-specific Antigen Density,

4Kscore and Risk Calculators. Eur Urol Oncol, 2019. 3: 700.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31548130/

57. Carter, H.B., et al. Early detection of prostate cancer: AUA Guideline. J Urol, 2013. 190: 419.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23659877/

58. Drazer, M.W., et al. National Prostate Cancer Screening Rates After the 2012 US Preventive Services

Task Force Recommendation Discouraging Prostate-Specific Antigen-Based Screening. J Clin

Oncol, 2015. 33: 2416.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26056181/

59. Shah, N., et al. Prostate Biopsy Characteristics: A Comparison Between the Pre- and Post-2012

United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) Prostate Cancer Screening Guidelines. Rev

Urol, 2018. 20: 77.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30288144/

60. Siegel, R.L., et al. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin, 2019. 69: 7.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30620402/

61. Kelly, S.P., et al. Past, Current, and Future Incidence Rates and Burden of Metastatic Prostate

Cancer in the United States. Eur Urol Focus, 2018. 4: 121.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29162421/

62. Fenton, J.J., et al. Prostate-Specific Antigen-Based Screening for Prostate Cancer: Evidence Report

and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Jama, 2018. 319: 1914.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29801018/

63. Grossman, D.C., et al. Screening for Prostate Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force

Recommendation Statement. JAMA, 2018. 319: 1901.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29801017/

64. Bibbins-Domingo, K., et al. The US Preventive Services Task Force 2017 Draft Recommendation

Statement on Screening for Prostate Cancer: An Invitation to Review and Comment. JAMA, 2017.

317: 1949. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28397958/

65. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Prostate Cancer Screening Draft Recommendations. 2017.

[Access date March 2022]. https://screeningforprostatecancer.org/

66. Arnsrud Godtman, R., et al. Opportunistic testing versus organized prostate-specific antigen

screening: outcome after 18 years in the Goteborg randomized population-based prostate cancer

screening trial. Eur Urol, 2015. 68: 354. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25556937/

67. Ilic, D., et al. Screening for prostate cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2013: CD004720.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23440794/

68. Hayes, J.H., et al. Screening for prostate cancer with the prostate-specific antigen test: a review of

current evidence. JAMA, 2014. 311: 1143. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24643604/

69. Borghesi, M., et al. Complications After Systematic, Random, and Image-guided Prostate Biopsy.

Eur Urol, 2017. 71: 353. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27543165/

70. Booth, N., et al. Health-related quality of life in the Finnish trial of screening for prostate cancer. Eur

Urol, 2014. 65: 39. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23265387/

71. Vasarainen, H., et al. Effects of prostate cancer screening on health-related quality of life: results of

the Finnish arm of the European randomized screening trial (ERSPC). Acta Oncol, 2013. 52: 1615.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23786174/

72. Heijnsdijk, E.A., et al. Quality-of-life effects of prostate-specific antigen screening. N Engl J Med,

2012. 367: 595. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22894572/

73. Martin, R.M., et al. Effect of a Low-Intensity PSA-Based Screening Intervention on Prostate Cancer

Mortality: The CAP Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA, 2018. 319: 883. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29509864/

74. Sanchez-Ortiz, R.F., et al. African-American men with nonpalpable prostate cancer exhibit greater

tumor volume than matched white men. Cancer, 2006. 107: 75. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16736511/

75. Bancroft, E.K., et al. Targeted Prostate Cancer Screening in BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutation Carriers:

Results from the Initial Screening Round of the IMPACT Study. Eur Urol, 2014. 66: 489.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24484606/

76. Gulati, R., et al. Screening Men at Increased Risk for Prostate Cancer Diagnosis: Model Estimates of

Benefits and Harms. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 2017. 26: 222.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27742670/

77. Guyatt, G.H., et al. Going from evidence to recommendations. BMJ, 2008. 336: 1049.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18467413/

78. Culp, M.B., et al. Recent Global Patterns in Prostate Cancer Incidence and Mortality Rates. Eur Urol,

2020. 77: 38.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31493960/

79. IARC, Data visualization tools for exploring the global cancer burden in 2020. [Access date March

2022].

https://gco.iarc.fr/today/home

80. Haas, G.P., et al. The worldwide epidemiology of prostate cancer: perspectives from autopsy

studies. Can J Urol, 2008. 15: 3866.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18304396/

81. Bell, K.J., et al. Prevalence of incidental prostate cancer: A systematic review of autopsy studies. Int

J Cancer, 2015. 137: 1749.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25821151/

82. Kimura, T., et al. Global Trends of Latent Prostate Cancer in Autopsy Studies. Cancers (Basel),

2021. 13.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33478075/

83. Fleshner, K., et al. The effect of the USPSTF PSA screening recommendation on prostate cancer

incidence patterns in the USA. Nat Rev Urol, 2017. 14: 26.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27995937/

84. Hemminki, K. Familial risk and familial survival in prostate cancer. World J Urol, 2012. 30: 143.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22116601/

85. Jansson, K.F., et al. Concordance of tumor differentiation among brothers with prostate cancer. Eur

Urol, 2012. 62: 656.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22386193/

86. Randazzo, M., et al. A positive family history as a risk factor for prostate cancer in a populationbased

study with organised prostate-specific antigen screening: results of the Swiss European

Randomised Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC, Aarau). BJU Int, 2016. 117: 576.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26332304/

87. Beebe-Dimmer, J.L., et al. Risk of Prostate Cancer Associated With Familial and Hereditary Cancer

Syndromes. J Clin Oncol, 2020. 38: 1807.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32208047/

88. Bratt, O., et al. Family History and Probability of Prostate Cancer, Differentiated by Risk Category: A

Nationwide Population-Based Study. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2016. 108.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27400876/

89. Schumacher, F.R., et al. Association analyses of more than 140,000 men identify 63 new prostate

cancer susceptibility loci. Nat Genet, 2018. 50: 928.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29892016/

90. Giri, V.N., et al. Germline genetic testing for inherited prostate cancer in practice: Implications for

genetic testing, precision therapy, and cascade testing. Prostate, 2019. 79: 333.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30450585/

91. Nicolosi, P., et al. Prevalence of Germline Variants in Prostate Cancer and Implications for Current

Genetic Testing Guidelines. JAMA Oncol, 2019. 5: 523.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30730552/

92. Castro, E., et al. PROREPAIR-B: A Prospective Cohort Study of the Impact of Germline DNA Repair

Mutations on the Outcomes of Patients With Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. J Clin

Oncol, 2019. 37: 490.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30625039/

93. Nyberg, T., et al. Prostate Cancer Risks for Male BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutation Carriers: A

Prospective Cohort Study. Eur Urol, 2020. 77: 24.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31495749/

94. Castro, E., et al. Effect of BRCA Mutations on Metastatic Relapse and Cause-specific Survival After

Radical Treatment for Localised Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol, 2015. 68: 186.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25454609/

95. Page, E.C., et al. Interim Results from the IMPACT Study: Evidence for Prostate-specific Antigen

Screening in BRCA2 Mutation Carriers. Eur Urol, 2019. 76: 831.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31537406/

96. Lippi, G., et al. Fried food and prostate cancer risk: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Food

Sci Nutr, 2015. 66: 587.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26114920/

97. Ploussard, G., et al. Decreased accuracy of the prostate cancer EAU risk group classification in the

era of imaging-guided diagnostic pathway: proposal for a new classification based on MRI-targeted

biopsies and early oncologic outcomes after surgery. World J Urol, 2020. 38: 2493.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31838560/

98. Ceci, F., et al. E-PSMA: the EANM standardized reporting guidelines v1.0 for PSMA-PET. Eur J Nucl

Med Mol Imaging, 2021. 48: 1626.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33604691/

99. van den Bergh, R.C.N., et al. Re: Andrew Vickers, Sigrid V. Carlsson, Matthew Cooperberg. Routine

Use of Magnetic Resonance Imaging for Early Detection of Prostate Cancer Is Not Justified by the

Clinical Trial Evidence. Eur Urol 2020;78:304-6: Prebiopsy MRI: Through the Looking Glass. Eur

Urol, 2020. 78: 310.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32660749/

100. Epstein, J.I., et al. The 2005 International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Consensus

Conference on Gleason Grading of Prostatic Carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol, 2005. 29: 1228.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16096414/

101. Epstein, J.I., et al. The 2014 International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Consensus

Conference on Gleason Grading of Prostatic Carcinoma: Definition of Grading Patterns and

Proposal for a New Grading System. Am J Surg Pathol, 2016. 40: 244.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26492179/

102. van Leenders, G., et al. The 2019 International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Consensus

Conference on Grading of Prostatic Carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol, 2020. 44: e87.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32459716/

103. Epstein, J.I., et al. A Contemporary Prostate Cancer Grading System: A Validated Alternative to the

Gleason Score. Eur Urol, 2016. 69: 428.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26166626/

104. Preisser, F., et al. Intermediate-risk Prostate Cancer: Stratification and Management. Eur Urol Oncol,

2020. 3: 270. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32303478/

105. Moyer, V.A. Screening for prostate cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation

statement. Ann Intern Med, 2012. 157: 120.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22801674/

106. Anderson, B.B., et al. Extraprostatic Extension Is Extremely Rare for Contemporary Gleason Score 6

Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol, 2017. 72: 455. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27986368/

107. Ross, H.M., et al. Do adenocarcinomas of the prostate with Gleason score (GS) <6 have the

potential to metastasize to lymph nodes? Am J Surg Pathol, 2012. 36: 1346.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22531173/

108. Goel, S., et al. Concordance Between Biopsy and Radical Prostatectomy Pathology in the Era of

Targeted Biopsy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Eur Urol Oncol, 2020. 3: 10.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31492650/

109. Inoue, L.Y., et al. Modeling grade progression in an active surveillance study. Stat Med, 2014.

33: 930. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24123208/

110. Van der Kwast, T.H., et al. Defining the threshold for significant versus insignificant prostate cancer.

Nat Rev Urol, 2013. 10: 473. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23712205/

111. Overland, M.R., et al. Active surveillance for intermediate-risk prostate cancer: yes, but for whom?

Curr Opin Urol, 2019. 29: 605. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31436567/

112. Kasivisvanathan, V., et al. MRI-Targeted or Standard Biopsy for Prostate-Cancer Diagnosis. N Engl

J Med, 2018. 378: 1767.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29552975/

113. Ahmed, H.U., et al. Diagnostic accuracy of multi-parametric MRI and TRUS biopsy in prostate

cancer (PROMIS): a paired validating confirmatory study. Lancet, 2017. 389: 815.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28110982/

114. Thompson, J.E., et al. Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging guided diagnostic biopsy

detects significant prostate cancer and could reduce unnecessary biopsies and over detection: a

prospective study. J Urol, 2014. 192: 67. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24518762/

119. Ilic, D., et al. Prostate cancer screening with prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test: a systematic

review and meta-analysis. Bmj, 2018. 362: k3519.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30185521/

120. Eklund, M., et al. MRI-Targeted or Standard Biopsy in Prostate Cancer Screening. N Engl J Med,

2021. 385: 908. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34237810/

121. Eldred-Evans, D., et al. Population-Based Prostate Cancer Screening With Magnetic Resonance

Imaging or Ultrasonography: The IP1-PROSTAGRAM Study. JAMA Oncol, 2021. 7: 395.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33570542/

122. Brandt, A., et al. Age-specific risk of incident prostate cancer and risk of death from prostate cancer

defined by the number of affected family members. Eur Urol, 2010. 58: 275.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20171779/

123. Carlsson, S., et al. Screening for Prostate Cancer Starting at Age 50-54 Years. A Population-based

Cohort Study. Eur Urol, 2017. 71: 46. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27084245/

124. Albright, F., et al. Prostate cancer risk prediction based on complete prostate cancer family history.

Prostate, 2015. 75: 390. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25408531/

125. Kamangar, F., et al. Patterns of cancer incidence, mortality, and prevalence across five continents:

defining priorities to reduce cancer disparities in different geographic regions of the world. J Clin

Oncol, 2006. 24: 2137. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16682732/

126. Chornokur, G., et al. Disparities at presentation, diagnosis, treatment, and survival in African

American men, affected by prostate cancer. Prostate, 2011. 71: 985.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21541975/

127. Karami, S., et al. Earlier age at diagnosis: another dimension in cancer disparity? Cancer Detect

Prev, 2007. 31: 29.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17303347/

128. Schoots, I.G., et al. Risk-adapted biopsy decision based on prostate magnetic resonance imaging

and prostate-specific antigen density for enhanced biopsy avoidance in first prostate cancer

diagnostic evaluation. BJU Int, 2021. 127: 175. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33089586/

129. Deniffel, D., et al. Avoiding Unnecessary Biopsy: MRI-based Risk Models versus a PI-RADS and

PSA Density Strategy for Clinically Significant Prostate Cancer. Radiology, 2021: 204112. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34032510/

130. Boesen, L., et al. Prebiopsy Biparametric Magnetic Resonance Imaging Combined with Prostatespecific

Antigen Density in Detecting and Ruling out Gleason 7-10 Prostate Cancer in Biopsy-naive

Men. Eur Urol Oncol, 2019. 2: 311. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31200846/

131. Falagario, U.G., et al. Avoiding Unnecessary Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and Biopsies:

Negative and Positive Predictive Value of MRI According to Prostate-specific Antigen Density,

4Kscore and Risk Calculators. Eur Urol Oncol, 2019. 3: 700.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31548130/

132. Knaapila, J., et al. Prebiopsy IMPROD Biparametric Magnetic Resonance Imaging Combined with

Prostate-Specific Antigen Density in the Diagnosis of Prostate Cancer: An External Validation Study.

Eur Urol Oncol, 2019. 6: 30134.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31501082/

133. Giri, V.N., et al. Implementation of Germline Testing for Prostate Cancer: Philadelphia Prostate

Cancer Consensus Conference 2019. J Clin Oncol, 2020. 38: 2798.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32516092/

134. John, E.M., et al. Prevalence of pathogenic BRCA1 mutation carriers in 5 US racial/ethnic groups.

Jama, 2007. 298: 2869.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18159056/

135. Richie, J.P., et al. Effect of patient age on early detection of prostate cancer with serum prostatespecific

antigen and digital rectal examination. Urology, 1993. 42: 365.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7692657/

136. Carvalhal, G.F., et al. Digital rectal examination for detecting prostate cancer at prostate specific

antigen levels of 4 ng./ml. or less. J Urol, 1999. 161: 835.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10022696/

137. Gosselaar, C., et al. The role of the digital rectal examination in subsequent screening visits in the

European randomized study of screening for prostate cancer (ERSPC), Rotterdam. Eur Urol, 2008.

54: 581.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18423977/

138. Hofman, M.S., et al. Prostate-specific membrane antigen PET-CT in patients with high-risk prostate

cancer before curative-intent surgery or radiotherapy (proPSMA): a prospective, randomised,

multicentre study. Lancet, 2020. 395: 1208.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32209449/

Author Correspondence:

Prof. Dr. Semir A. Salim. Al Samarrai

Medical Director of Professor Al Samarrai Medical Center.

Dubai Healthcare City, Al-Razi Building 64, Block D, 2nd Floor, Suite 2018

E-mail: semiralsamarrai@hotmail.com

Tel: +97144233669