Renal Cell Carcinoma

Part 2

Comprehensive Review Article

Prof. Dr. Semir. A. Salim. Al Samarrai

Treatment of localised RCC:

- Introduction

Randomised or quasi-RCTs were included. However, due to the very limited number of RCTs, non-randomised studies (NRS), prospective observational studies with controls, retrospective matched-pair studies, and comparative studies from the databases of well-defined registries were also included. Historically, surgery has been the benchmark for the treatment of localised RCC.

- Surgical treatment

- Nephron-sparing surgery versus radical nephrectomy in localised RCC

- T1 RCC

Most studies comparing the oncological outcomes of Partial Nephrectomy (PN) and Radical Nephrectomy (RN) are retrospective and include cohorts of varied and, overall, limited size [1,2]. There is only one, prematurely closed, prospective RCT including patients with organ-confined RCCs of limited size (< 5 cm), showing comparable non-inferiority of CSS for PN vs. RN (HR: 2.06 [95% CI: 0.62–6.84]) [3].

Partial nephrectomy preserved kidney function better after surgery, thereby potentially lowering the risk of development of cardiovascular disorders [1, 4–8]. When compared with a radical surgical approach, several retrospective analyses of large databases have suggested a decreased cardiovascular-specific mortality [5, 9] as well as improved OS for PN compared to RN. However, in some series this held true only for younger patients and/or patients without significant comorbidity at the time of the surgical intervention [10, 11]. An analysis of the U.S. Medicare database [12] could not demonstrate an OS benefit for patients > 75 years of age when RN or PN were compared with non-surgical management. Conversely, another series that addressed this question and also included Medicare patients, suggested an OS benefit in older patients (75–80 years) when subjected to surgery rather than non-surgical management. Shuch et al. compared patients who underwent PN for RCC with a non-cancer healthy control group via a retrospective database analysis; showing an OS benefit for the cancer cohort [13]. These conflicting results may be an indication that unknown statistical confounders hamper the retrospective analysis of population-based tumour registries. In the only prospectively randomised, but prematurely closed, heavily underpowered, trial, PN seems to be less effective than RN in terms of OS in the intention to treat (ITT) population (HR: 1.50 [95% CI: 1.03–2.16]). However, in the targeted RCC population of the only RCT, the trend in favour of RN was no longer significant [3]. Taken together, the OS advantage suggested for PN vs. RN remains an unresolved issue. Patients with a normal pre-operative renal function and a decreased GFR due to surgical treatment (either RN or PN), generally present with stable long-term renal function [8]. Adverse OS in patients with a pre-existing GFR reduction does not seem to result from further renal function impairment following surgery, but rather from other medical comorbidities causing pre-surgical chronic kidney disease (CKD) [14]. However, in particular in patients with pre-existing CKD, PN is the treatment of choice to limit the risk of development of ESRD which requires haemodialysis. Huang et al. found that 26% of patients with newly diagnosed RCC had an GFR < 60 mL/min, even though their baseline serum creatinine levels were in the normal range [15].

In terms of the intra- and peri-operative morbidity/complications associated with PN vs. RN, the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) randomised trial showed that PN for small, easily resectable, incidentally discovered RCC, in the presence of a normal contralateral kidney, can be performed safely with slightly higher complication rates than after RN [16]. Only a limited number of studies are available addressing quality of life (QoL) following PN vs. RN, irrespective of the surgical approach used (open vs. minimally invasive). Quality of life was ranked higher following PN as compared to RN, but in general patients’ health status deteriorated following both approaches [16, 17]. In view of the above, and since oncological safety (CSS and RFS) of PN, so far, has been found non-differing from RN outcomes, PN is the treatment of choice for T1 RCC since it preserves kidney function better and in the long term potentially limits the incidence of cardiovascular disorders. Whether decreased mortality from any cause can be attributed to PN is still unresolved, but in patients with pre-existing CKD, PN is the preferred surgical treatment option as it avoids further deterioration of kidney function; the latter being associated with a higher risk of development of ESRD and the need for haemodialysis. Irrespective of the available data, in frail patients, treatment decisions should be individualised, weighing the risks and benefits of PN vs. RN, the increased risk of peri-operative complications and the risk of developing or worsening CKD post-operatively.

- T2 RCC

There is very limited evidence on the optimal surgical treatment for patients with larger renal masses (T2). Some retrospective comparative studies of PN vs. RN for T2 RCC have been published [18]. A trend for lower tumour recurrence- and cancer-specific mortality is reported in PN groups. The estimated blood loss is reported to be higher for PN groups, as is the likelihood of post-operative complications [18]. A recent multicentre study compared the survival outcomes in patients with larger (> 7 cm) ccRCC treated with PN vs. RN with long-term follow-up (median 102 months). Compared to the RN group, the PN group had a significantly longer median OS (p = 0.014) and median CSS (p = 0.04) [19]. Retrospective comparative studies of cT1 and cT2 RCC patients upstaged to pT3a RCC show contradictory results: some reports suggest similar oncologic outcomes between PN and RN [20], whilst another recent report suggests that PN of clinical T1 in pathologically upstaged pT3a of cT1 RCC is associated with a significantly shorter recurrence-free survival than RN [21]. Overall, the level of the evidence is low. These studies including T2 masses all have a high risk of selection bias due to imbalance between the PN and RN groups regarding patient’s age, comorbidities, tumour size, stage, and tumour position. These imbalances in covariation factors may have a greater impact on patient outcome than the choice of PN or RN. The EAU Guidelines 2022 Panel’s confidence in the results is limited and the true effects may be substantially different. In view of the above, the risks and benefits of PN should be discussed with patients with T2 tumours. In this setting PN should be considered, if technically feasible, in patients with a solitary kidney, bilateral renal tumours or CKD with sufficient parenchymal volume preserved to allow sufficient post-operative renal function.

- T3 RCC

A recent meta-analysis of nine articles including 1,278 patients with PN and 2,113 patients with RN in pT3a RCC showed no difference in CSS, OS, CSM and RFS, indicating that PN techniques can be used for functional benefits and if technically feasible [22].

Associated procedures:

- Adrenalectomy

One prospective non-randomised study compared the outcomes of RN with or without, ipsilateral adrenalectomy [23]. Multivariable analysis showed that upper pole location was not predictive of adrenal involvement, but tumour size was. No difference in OS at five or ten years was seen with, or without, adrenalectomy. Adrenalectomy was justified using criteria based on radiographic- and intra-operative findings. Only 48 of 2,065 patients underwent concurrent ipsilateral adrenalectomy of which 42 of the 48 interventions were for benign lesions [23].

- Lymph node dissection for clinically negative lymph nodes (cN0)

The indication for LN dissection (LND) together with PN or RN is still controversial [24]. The clinical assessment of LN status is based on the detection of an enlargement of LNs either by CT/MRI or intraoperative palpability of enlarged nodes. Less than 20% of suspected metastatic nodes (cN+) are positive for metastatic disease at histopathological examination (pN+) [25]. Both CT and MRI are unsuitable for detecting malignant disease in nodes of normal shape and size [26]. For clinically positive LNs (cN+). Smaller retrospective studies have suggested a clinical benefit associated with a more or less extensive LND preferably in patients at high risk for lymphogenic spread. In a large retrospective study, the outcomes of RN, with or without LND, in patients with high-risk non-mRCC were compared using a propensity score analysis. In this study LND was not significantly associated with a reduced risk of distant metastases, cancer-specific or all-cause mortality. The extent of the LND was not associated with improved oncologic outcomes [27]. The number of LN metastases (< / > 4) as well as the intra- and extracapsular extension of intra-nodal metastasis correlated with the patients´ clinical prognosis in some studies [26, 28-30]. Better survival outcomes were seen in patients with a low number of positive LNs (< 4) and no extranodal extension. On the basis of a retrospective Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database analysis of > 9,000 patients no effects of an extended LND (eLND) on the disease-specific survival (DSS) of patients with pathologically confined negative nodes was demonstrated [31]. However, in patients with pathologically proven lymphogenic spread (pN+), an increase of 10 for the number of nodes dissected resulted in a 10% absolute increase in DSS.

In addition, in a larger cohort of 1,983 patients, Capitanio et al. demonstrated that eLND results in a significant prolongation of CSS in patients with unfavourable prognostic features (e.g., sarcomatoid differentiation, large tumour size) [282]. As to morbidity related to eLND, a recent retrospective propensity score analysis from a large single-centre database showed that eLND is not associated with an increased risk of Clavien grade > 3 complications. Furthermore, LND was not associated with length of hospital stay or estimated blood loss [33]. Only one prospective RCT evaluating the clinical value of LND combined with surgical treatment of primary RCC has been published so far. With an incidence of LN involvement of only 4%, the risk of lymphatic spread appears to be very low. Recognising the latter, only a staging effect was attributed to LND [25]. This trial included a very high percentage of patients with pT2 tumours, which are not at increased risk for LN metastases. Only 25% of patients with pT3 tumours underwent a complete LND and the LN template used by the authors was not clearly stated. The optimal extent of LND remains controversial. Retrospective studies suggest that an eLND should involve the LNs surrounding the ipsilateral great vessel and the inter-aortocaval region from the crus of the diaphragm to the common iliac artery. Involvement of inter-aortocaval LNs without regional hilar involvement is reported in up to 35–45% of cases [26, 34, 35]. At least fifteen LNs should be removed [32, 36]. Sentinel LND is an investigational technique [37, 38].

- Embolisation

Before routine nephrectomy, tumour embolisation has no benefit [39, 40]. In patients unfit for surgery, or with non-resectable disease, embolisation can control symptoms, including visible haematuria or flank pain [41, 42].

Radical and partial nephrectomy techniques:

- Radical nephrectomy techniques

No RCTs have assessed the oncological outcomes of laparoscopic vs. open RN. A cohort study [43] and retrospective database reviews are available, mostly of low methodological quality, showing similar oncological outcomes even for higher stage disease and locally more advanced tumours [44-46]. Based on a systematic review, less morbidity was found for laparoscopic vs. open RN [1]. Data from one RCT [18] and two non-randomised studies [47,48] showed a significantly shorter hospital stay and lower analgesic requirement for the laparoscopic RN group as compared with the open group. Convalescence time was also significantly shorter [48]. No difference in the number of patients receiving blood transfusions was observed, but peri-operative blood loss was significantly less in the laparoscopic arm in all three studies [45, 47, 48]. Surgical complication rates were low with very wide confidence intervals. There was no difference in complications, but operation time was significantly shorter in the open nephrectomy arm. Post-operative QoL scores were similar [47]. Some comparative studies focused on the peri-operative outcomes of laparoscopic vs. RN for renal > T2 tumours. Overall, patients who underwent laparoscopic RN were shown to have lower estimated blood loss, less post-operative pain, shorter length of hospital stay and convalescence compared to those who underwent open RN [46, 48, 49]. Intra-operative and post-operative complications were similar in the two groups and no significant differences in CSS, PFS and OS were reported [46, 48, 49]. Another multicentre propensity matched analysis compared laparoscopic- and open surgery for pT3a RCC, showing no significant difference in three-year RFS between groups [50]. The best approach for laparoscopic RN was the retroperitoneal or transperitoneal approach with similar oncological outcomes in two RTCs [51, 52] and one quasi-randomised study [26]. Quality of life variables were similar for both approaches. Hand-assisted vs. standard laparoscopic RN was compared in one quasi-randomised study [53] and one database review and estimated five-year OS, CSS, and RFS rates were comparable [54]. Duration of surgery was significantly shorter in the hand-assisted approach, while length of hospital stays and time to non-strenuous activities were shorter for the standard laparoscopic RN cohort [53, 54]. However, the sample size was small. Data of a large retrospective cohort study on robot-assisted laparoscopic vs. laparoscopic RN showed robot-assisted laparoscopic RN was not associated with increased risk of any or major complications but had a longer operating time and higher hospital costs compared with laparoscopic RN [55]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of seven studies with 1,832 patients showed no difference between the two approaches in peri-operative outcomes, including operative time, blood loss, conversion rates and complications [56]. A systematic review reported on robot-assisted laparoscopic vs. conventional laparoscopic RN, showing no substantial differences in local recurrence rates, nor in all-cause cancer-specific mortality [57]. Similar results were seen in observational cohort studies comparing ‘portless’ and 3-port laparoscopic RN, with similar perioperative outcomes [58, 59].

Partial nephrectomy techniques:

- Open versus laparoscopic approach

Studies comparing laparoscopic and open PN found no difference in PFS [60–63] and OS [62, 63] in centres with laparoscopic expertise. However, the oncological safety of laparoscopic vs. open PN has, so far, only been addressed in studies with relatively limited follow-up [50]. However, the higher number of patients treated with open surgery in this series might reflect a selection bias by offering laparoscopic surgery in case of a less complex anatomy [50]. The mean estimated blood loss was found to be lower with the laparoscopic approach [60, 62, 64], while post-operative mortality, deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism events were similar [60, 62]. Operative time is generally longer with the laparoscopic approach [61–63] and warm ischaemia time is shorter with the open approach [60, 62, 64, 65]. In a matched-pair comparison, GFR decline was greater in the laparoscopic PN group in the immediate post-operative period [63], but not after 3.6 years follow-up. In another comparative study, the surgical approach was not an independent predictor for post-operative CKD [65]. Retroperitoneal and transperitoneal laparoscopic PN have similar peri-operative outcomes [66]. Simple tumour enucleation also had similar PFS and CSS rates compared to standard PN and RN in a large study [67]. The feasibility of laparo-endoscopic single-site PN has been shown in selected patients but larger studies are needed to confirm its safety and clinical role [68].

- Open versus robotic approach

One study prospectively compared the peri-operative outcomes of a series of robot-assisted and open PN performed by the same experienced surgeon. Robot-assisted PN was superior to open PN in terms of lower estimated blood loss and shorter hospital stay. Warm ischaemia time, operative time, immediate- early- and short-term complications, variation in creatinine levels and pathologic margins were similar between groups [69]. A multicentre French prospective database compared the outcomes of 1,800 patients who underwent open PN and robot-assisted PN. Although the follow-up was shorter, there was a decreased morbidity in the robot-assisted PN group with less overall complications, less major complications, less transfusions and a much shorter hospital stay [70].

- Open versus hand-assisted approach

Hand-assisted laparoscopic PN (HALPN) is rarely performed. A recent comparative study of open vs. HALPN showed no difference in OS or RFS at intermediate-term follow-up. The authors observed a lower rate of intraoperative and all-grade post-operative 30-day complications in HALPN vs. open PN patients, but there was no significant difference in high Clavien grade complications. Three months after the operation, GFR was lower in the HALPN than in the open PN group [71].

- Open versus laparoscopic versus robotic approaches

In a retrospective propensity-score-matched study, comparing open-, laparoscopic- and robot-assisted PN, after five-year of median follow-up, similar rates of local recurrence, distant metastasis and cancer-related death rates were found [72].

- Laparoscopic versus robotic approach

Another study included the 50 last patients having undergone laparoscopic and robotic PN for T1-T2 renal tumours by two different surgeons with an experience of over 200 procedures each in laparoscopic and robotic PN and robot-assisted partial nephrectomy (RAPN), respectively, at the beginning of the study. Peri-operative and short-term oncological and functional outcomes appeared broadly comparable between RAPN and LPN when performed by highly experienced surgeons [73]. A meta-analysis, including a series of NSS with variable methodological quality compared the peri-operative outcomes of robot-assisted- and laparoscopic PN. The robotic group had a significantly lower rate of conversion to open surgery and to radical surgery, shorter warm ischaemia time, smaller change in estimated GFR after surgery and shorter length of hospital stay. No significant differences were observed between the two groups regarding complications, change of serum creatinine after surgery, operative time, estimated blood loss and positive surgical margins [74]. A recent multi-institutional prospective study of 105 patients with hilar tumours demonstrated a reduced warm ischaemia time (20.2 min vs. 27.7 min) and a comparable PSM rate of 1.9% when compared with a historical laparoscopic control group which was defined by literature research and meta-analysis for warm ischaemia time and PSM, respectively [75].

- Surgical volume

In a recent analysis of 8,753 patients who underwent PN, an inverse non-linear relationship of hospital volume with morbidity of PN was observed, with a plateauing seen at 35 to 40 cases per year overall, and 18 to 20 cases for the robotic approach [76]. A retrospective study of a U.S. National Cancer Database looked at the prognostic impact of hospital volume and the outcomes of robot-assisted PN, including 18,724 cases. This study shows that undergoing RAPN at higher-volume hospitals may have better peri-operative outcomes (conversion to open and length of hospital stay) and lower positive surgical margin rates [77]. A French study, including 1,222 RAPN patients, has shown that hospital volume is the main predictive factor of Trifecta achievement (no complications, warm ischaemia time < 25 min, and negative surgical margins) after adjustment for other variables, including surgeon volume [78]. The prospective Registry of Conservative and Radical Surgery for cortical renal tumour Disease (RECORd-2) study including 2,076 patients showed that the hospital volume (> 60 PN/year) is an independent predictor for positive surgical margins [79].

- Pre-operative embolisation prior to partial nephrectomy

A systematic review and meta-analysis of 270 patients demonstrated significantly reduced blood loss in patients with selective renal artery embolisation (n = 222; 154 ± 22.6 mL vs. n = 48; 353.4 ± 69.6 mL) prior to partial nephrectomy [80].

- Positive surgical margins on histopathological specimens

A positive surgical margin is encountered in about 2–8% of PNs [74]. Studies comparing surgical margins with different surgical approaches (open, laparoscopic, robotic) are inconclusive [81, 82]. Most trials showed that intra-operative frozen section analysis had no influence on the risk of definite positive surgical margins [83]. A positive surgical margin status occurs more frequently in cases in which surgery is imperative (solitary kidneys and bilateral tumours) and in patients with adverse pathological features (pT2a, pT3a, grade III-IV) [85-87]. The potential negative impact of a positive margin status on the oncologic outcome is still controversial [81]. The majority of retrospective analyses reported so far indicated that positive surgical margins do not translate into a higher risk of metastases or a decreased CSS [85, 86]. On the other hand, another retrospective study of a large single institutional series showed that positive surgical margins are an independent predictor of PFS due to a higher incidence of distant and local relapses [88]. Another retrospective study of 42,114 PN patients with 2,823 PSM patients (6.7%) showed an increased presence of PSM in upstaged pT3a tumours (14.1%), increased all-cause mortality in PSM patients and a decreased five-year OS rate in pT3a tumours (PSM: 69% vs. NSM: 90.9 %) [340]. However, only a proportion of patients with an uncertain margin status actually harbour residual malignancy [90]. Local tumour bed recurrences were found in 16% in patients with positive surgical margins compared with 3% in those with negative margins [84], Therefore, RN or re-resection of margins can result in over-treatment in many cases. Patients with positive surgical margins should be informed that they will need a more intense surveillance (imaging) follow-up and that they are at increased risk of secondary local therapies [85, 91]. On the other hand, protection from recurrence is not ensured by negative surgical margins [92].

Therapeutic approaches as alternatives to surgery:

- Surgical versus non-surgical treatment

Population-based studies compared the oncological outcomes of surgery (RN or PN) and non-surgical management for tumours < 4 cm. The analyses showed a significantly lower cancer-specific mortality in patients treated with surgery [12, 93, 94]. However, the patients assigned to the surveillance arm were older and likely to be frailer and less suitable for surgery. Other-cause mortality rates in the non-surgical group significantly exceeded that of the surgical group [93]. Analyses of older patients (> 75 years) failed to show the same benefit in cancer-specific mortality for surgical treatment [95–97].

- Active surveillance and watchful waiting

Elderly and comorbid patients with incidental small renal masses have a low RCC-specific mortality and significant competing-cause mortality [98, 99]. Active surveillance is defined as the initial monitoring of tumour size by serial abdominal imaging (US, CT, or MRI) with delayed intervention reserved for tumours showing clinical progression during follow-up [100]. The concept of AS differs from the concept of watchful waiting; watchful waiting is reserved for patients whose comorbidities contraindicate any subsequent active treatment and do not require follow-up imaging, unless clinically indicated. In the largest reported series of AS the growth of renal tumours was low and progression to metastatic disease was reported in only a limited number of patients [101, 102]. A single-institutional comparative study evaluating patients aged > 75 years showed decreased OS for those who underwent surveillance and nephrectomy relative to NSS for clinically T1 renal tumours. However, at multivariate analysis, management type was not associated with OS after adjusting for age, comorbidities, and other variables [98]. No statistically significant differences in OS and CSS were observed in another study of RN vs. PN vs. AS for T1a renal masses with a follow-up of 34 months [103]. The prospective non-randomised multi-institutional Delayed Intervention and Surveillance for Small Renal Masses (DISSRM) study enrolled 497 patients with solid renal masses < 4 cm who selected either AS or primary active intervention. Patients who selected AS were older, had worse ECOG scores, more comorbidities, smaller tumours, and more often had multiple and bilateral lesions. In patients who elected AS in this study the overall median small renal mass growth rate was 0.09 cm/year with a median follow-up of 1.83 years. The growth rate and variability decreased with longer follow-up. No patients developed metastatic disease or died of RCC [104, 105]. Overall survival for primary intervention and AS was 98% and 96% at two years, and 92% and 75% at five years, respectively (p = 0.06). At five years, CSS was 99% and 100%, respectively (p = 0.3). Active surveillance was not predictive of OS or CSS in regression modelling with relatively short follow-up [104]. Overall, both short- and intermediate-term oncological outcomes indicate that in selected patients with advanced age and/or comorbidities, AS is appropriate for initially monitoring of small renal masses, followed, if required, by treatment for progression [100–102, 106–109]. A multicentre study assessed QoL of patients undergoing immediate intervention vs. AS. Patients undergoing immediate intervention had higher QoL scores at baseline, specifically for physical health. The perceived benefit in physical health persisted for at least one year following intervention. Mental health, which includes domains of depression and anxiety, was not adversely affected while on AS [110]. In 136 biopsy-proven small renal mass (SRM) RCCs managed by AS median follow-up for patients who remained on AS was 5.8 years (interquartile range 3.4-7.5 years). Clear cell RCC grew faster than papillary type 1 SRMs (0.25 and 0.02 cm/year on average, respectively, p = 0.0003). Overall, 60 (44.1 %) of the malignant SRM progressed: 49 (82%) by rapid growth (volume doubling), seven (12%) increasing to > 4 cm, and four (6.7%) by both criteria. Six patients developed metastases, and all were of ccRCC histology [111].

Tumour ablation:

- Role of renal mass biopsy

A RMB is required prior to tumour ablation (TA). Historically, up to 45% of patients underwent TA of a benign or non-diagnostic mass [112, 113]. A RMB in a separate session reduces over-treatment significantly, with 80% of patients with benign lesions opting not to proceed with TA [113]. Additionally, there is some evidence that the oncological outcome following TA differs according to RCC subtype which should therefore be factored into the decision-making process. In a series of 229 patients with cT1a tumours (mean size 2.5 cm) treated with RFA, the five-year DFS rate was 90% for ccRCC and 100% for pRCC (80 months: 100% vs. 87%, p = 0.04) [114]. In another series, the total TA effectiveness rate was 90.9% for ccRCC and 100% for pRCC [115]. A study comparing RFA with surgery suggested worse outcomes of RFA vs. PN in cT1b ccRCC, while no difference was seen in those with non-ccRCC [116]. Furthermore, patients with high-grade RCC or metastasis may choose different treatments over TA. Finally, patients without biopsy or a non-diagnostic biopsy are often assumed to have RCC and will undergo potentially unnecessary radiological follow-up or further treatment.

- Cryoablation

Cryoablation is performed using either a percutaneous- or a laparoscopic-assisted approach, with technical success rates of > 95% [117]. In comparative studies, there was no significant difference in the overall complication rates between laparoscopic- and percutaneous cryoablation [118–120]. One comparative study reported similar OS, CSS, and RFS in 145 laparoscopic patients with a longer follow-up vs. 118 patients treated percutaneously with a shorter follow-up [119]. A shorter average length of hospital stay was found with the percutaneous technique [119–121]. A systematic review including 82 articles reported complication rates ranging between 8 and 20% with most complications being minor [122]. Although a precise definition of tumour recurrence is lacking, the authors reported a lower RFS as compared to that of PN. Oncological outcomes after cryoablation have generally been favourable for cT1a tumours. In a recently published series of 308 patients with cT1a and cT1b tumours undergoing percutaneous cryoablation, local recurrence was seen in 7.7% of cT1a tumours vs. 34.5% of cT1b tumours. On multivariable regression, the risk of disease progression increased by 32% with each 1 cm increase in tumour size (HR: 1.32, p < 0.001). Mean decline in eGFR was 11.7 mL/min/1.73 m2 [123]. In another large series of 220 patients with biopsy proven cT1 RCC, five-year local RFS was 93.9%, while metastasis-free survival approached 94.4% [117]. A series of 134 patients with T1 RCC (median tumour size 2.8 cm) submitted to percutaneous cryoablation yielded a ten-year DSF of 94% [124]. For cT1b tumours, local tumour control rates drop significantly. One study showed local tumour control in only 60.3% at three years [125]. In another series, the PFS rate was 66.7% at twelve months [126]. Furthermore, recent analyses demonstrated five-year cancer-specific mortality rates of 7.6–9% [127, 128]. On multivariable analysis, cryoablation of cT1b tumours was associated a 2.5-fold increased risk of death from RCC compared with PN [127]. Recurrence after initial cryoablation is often managed with re-cryoablation, but only 45% of patients remain disease-free at two years [129].

- Radiofrequency ablation

Radiofrequency ablation is performed laparoscopically or percutaneously. Several studies compared patients with cT1a tumours treated by laparoscopic or percutaneous RFA [130–133]. Complications occurred in up to 29% of patients but were mostly minor. Complication rates, recurrence rates and CSS were similar in patients treated laparoscopically and percutaneously. The initial technical success rate on early (i.e., one month) imaging after one session of RFA is 94% for cT1a and 81% for cT1b tumours [134]. This is generally managed by re-RFA, approaching overall total technical success rates > 95% with one or more sessions [135]. Long-term outcomes with over five years of follow-up following RFA have been reported. In recent studies, the five-year OS rate was 73–79% [134, 135], due to patient selection. Oncological outcomes for cT1a tumours have been favourable. In a recent study, the ten-year disease-free survival rate was 82%, but there was a significant drop to 68% for tumours > 3 cm [386]. In series focusing on clinical T1b tumours (4.1–7.0 cm), the five-year DFS rate was 74.5% to 81% [134, 136]. Oncological outcomes appear to be worse than after surgery, but comparative data are severely biased. In general, most disease recurrences occur locally and recurrences beyond five years are rare [135, 136].

- Tumour ablation versus surgery

The EAU Guidelines 2022 Panel performed a protocol-driven systematic review of comparative studies (including > 50 patients) of TA with PN for T1N0M0 renal masses [137]. Twenty-six non-randomised comparative studies published between 2000 and 2019 were included, recruiting a total of 16,780 patients. Four studies compared laparoscopic TA vs. laparoscopic/robotic PN; sixteen studies compared laparoscopic or percutaneous TA vs. open-, laparoscopic- or robotic PN; two studies compared different techniques of TA and four studies compared TA vs. PN vs RN. In this systematic review, TA as treatment for T1 renal masses was found to be safe in terms of complications and adverse events (AEs), but its long-term oncological effectiveness compared with PN remained unclear. The primary reason for the persisting uncertainty was related to the nature of the available data; most studies were retrospective observational studies with poorly matched controls, or singlearm case series with short follow-up. Many studies were poorly described and lacked a clear comparator. There was also considerable methodological heterogeneity. Another major limitation was the absence of clearly defined primary outcome measures. Even when a clear endpoint such as OS was reported, data were difficult to interpret because of the varying length and type of follow-up amongst studies. The EAU Guidelines 2022 Panel also appraised the published systematic reviews based on the AMSTAR 2 tool which showed critically low or low ratings [137]. Tumour ablation has been demonstrated to be associated with good long-term survival in several single-arm non-comparative studies [138, 139]. Due to the lack of controls, this apparent benefit is subject to significant uncertainties. Whether such benefit is due to the favourable natural history of such tumours or due to the therapeutic efficacy of TA, as compared to PN, remains unknown. In addition, there are data from comparative studies suggesting TA may be associated with worse oncological outcomes in terms of local recurrence and metastatic progression and cancer-specific mortality [10, 127, 128, 140, 141]. However, there appears to be no clinically significant difference in five-year cancer-specific mortality between TA and AS [94]. The Panel of EAU guidelines edition 2022 concluded that the current data are inadequate to reach conclusions regarding the clinical effectiveness of TA as compared with PN. Given these uncertainties in the presence of only low-quality evidence, TA can only be recommended to frail and/or comorbid patients with small renal masses.

- Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy

Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (SABR) has been emerging as a treatment option for medically inoperable patients with localised cT1a and cT1b tumours. Patients usually receive 26 Gy in a single fraction, three fractions of 14 Gy or five fractions of 6 Gy [142, 143]. In a systematic review or non-comparative single-arm studies, the local control rate was 97.2% and the mean change in eGFR was 7.7 mL/min/1.73 m2. Grade 3 or 4 toxicities occurred in 1.5% of patients. However, viable tumour cells are often seen in post-SABR biopsies, although their clinical significance remains unclear [143]. Although early results of SABR are encouraging, more evidence from randomised trials is needed.

- Other ablative techniques

Some studies have shown the feasibility of other ablative techniques, such as microwave ablation, highintensity focused US ablation and non-thermal irreversible electroporation. However, these techniques are still considered experimental. The best evidence base for these techniques exists for percutaneous microwave ablation. In a study of 185 patients with a median follow-up of 40 months, the five-year local progression rate was 3.2%, while 4.3% developed distant metastases [144]. Results appear to be favourable for cT1b tumours as well [145]. Overall, current data on cryoablation, RFA and microwave ablation of cT1a renal tumours indicate short-term equivalence with regards to complications, oncological and renal functional outcomes [146].

Treatment of locally advanced RCC:

- Introduction

In addition to the summary of evidence and recommendations for localised RCC, certain therapeutic strategies arise in specific situations for locally advanced disease.

- Role of lymph node invasion in locally advanced RCC

In locally advanced RCC, the role of LND is still controversial. The only available RCT demonstrated no survival benefit for patients undergoing LND but this trial mainly included organ-confined disease cases [25]. In the setting of locally advanced disease, several papers addressed the topic with contradictory results, as did several systematic reviews. Bhindi et al. could not confirm any survival benefit in patients at high risk of progression treated with LND [147]. More recently, Luo et al. reported a systematic review and meta-analyses showing a survival benefit in patients with locally advanced disease treated with LND [148]. More specifically, thirteen studies on patients with LND and non-LND were identified and included in the analysis. In the subgroup of locally advanced RCC (cT3-T4NxM0), LND showed a significantly better OS rate in patients who had undergone LND compared to those without LND (HR: 0.73, 95% CI: 0.60–0.90, p = 0.003).

- Management of clinically negative lymph nodes (cN-) in locally advanced RCC

In case of cN-, the probability of finding pathologically confirmed LN metastases ranges between 0 and 25%, depending mainly on primary tumour size and the presence of distant metastases [149]. In case of clinically negative LNs (cN-) at imaging, removal of LNs is justified only if visible or palpable during surgery [150], at least for staging, prognosis and follow-up implications although a benefit in terms of cancer control has not yet been demonstrated [4, 147]. Whether to extend the LND also to retroperitoneal areas without cN+ remains controversial [26].

- Management of clinically positive lymph nodes (cN+) in locally advanced RCC

In case of cN+, the probability to find pathologically confirmed LN metastases ranges between 10.3% (cT1 tumours) up to 54.5% in case of locally advanced disease. In cN+, removal of visible and palpable nodes during lymphadenectomy is always justified [150], at least for staging, prognosis and follow-up implications, although a benefit in terms of cancer control has not yet been demonstrated [27, 147].

- Management of locally advanced unresectable RCC

In case of locally advanced unresectable RCC, a multi-disciplinary evaluation, including urologists, medical oncologists and radiation therapists is suggested to maximise cancer control, pain control and the best supportive care. In patients with non-resectable disease, embolisation can control symptoms, including visible haematuria or flank pain [41, 42, 151]. The use of systemic therapy to downsize tumours is experimental and cannot be recommended outside clinical trials.

- Management of RCC with venous tumour thrombus

Tumour thrombus formation in RCC patients is a significant adverse prognostic factor. Traditionally, patients with venous tumour thrombus undergo surgery to remove the kidney and tumour thrombus. Aggressive surgical resection is widely accepted as the default management option for patients with venous tumour thrombus [152–160].

- The evidence base for surgery in patients with venous tumour thrombus

Data whether patients with venous tumour thrombus should undergo surgery is derived from case series only. In one of the largest published studies a higher level of thrombus was not associated with increased tumour dissemination to LNs, perinephric fat or distant metastasis [157]. Therefore, all patients with non-metastatic disease and venous tumour thrombus, and an acceptable PS, should be considered for surgical intervention, irrespective of the extent of tumour thrombus at presentation. The surgical technique and approach for each case should be selected based on the extent of tumour thrombus.

- The evidence base for different surgical strategies

A systematic review was undertaken which included only comparative studies on the management of venous tumour thrombus in non-metastatic RCC [161, 162]. Only five studies were eligible for final inclusion, with a high risk of bias across all studies. Minimal access techniques resulted in significantly shorter operating time compared with traditional median sternotomy [163–166]. The surgical method selected depended on the level of tumour thrombus and the grade of occlusion of the IVC [161, 163, 164, 167]. The relative benefits and harms of other strategies and approaches regarding access to the IVC and the role of IVC filters and bypass procedures remain uncertain.

- Neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapy

Neoadjuvant therapy is currently under investigation and available in clinical trials. There is currently no evidence from a recent systematic review (including ten retrospective studies and two RCTs) that adjuvant radiation therapy increases survival [168]. The impact on OS of adjuvant tumour vaccination in selected patients undergoing nephrectomy for T3 renal carcinomas remains unconfirmed [169–173]. A similar observation was made in an adjuvant trial of girentuximab, a monoclonal antibody against carboanhydrase IX (CAIX) (ARISER Study) [174].

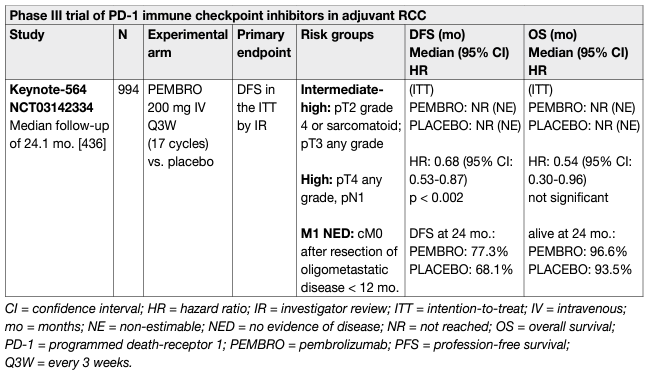

At present, there is no OS data supporting the use of adjuvant VEGFR or mTOR inhibitors. Thus far, several RCTs comparing VEGFR-TKI vs. placebo have been published [175–182]. One of the largest adjuvant trials compared sunitinib vs. sorafenib vs. placebo (ASSURE). Its interim results published in 2015 demonstrated no significant differences in DFS or OS between the experimental arms and placebo [141]. The study published its updated analysis on a subset of high-risk patients in 2018, which demonstrated five-year DFS rates of 47.7%, 49.9%, and 50.0%, respectively for sunitinib, sorafenib, and placebo and five-year OS of 75.2%, 80.2%, and 76.5%, respectively, without significant difference. The results indicated that adjuvant therapy with sunitinib or sorafenib have no survival effect [175, 176]. The PROTECT study included 1,135 patients treated with pazopanib (n = 571) vs. placebo (n = 564) in a 1:1 randomisation [177]. The primary endpoint was amended after 403 patients received a starting dose of pazopanib 800 mg vs. placebo, to DFS with pazopanib 600 mg. The primary analysis results of DFS in the ITT pazopanib 600 mg arm were not significant (HR: 0.86, 95% CI: 0.7–1.06, p = 0.16). Disease-free survival in the ITT pazopanib 800 mg population was improved (HR: 0.69, 95% CI: 0.51–0.94, p = 0.02). No benefit in OS was seen in the ITT pazopanib 600 mg population (HR: 0.79 [0.57–1.09, p = 0.16]). A subset analysis of these studies suggests that full-dose therapy is associated with improved DFS. Furthermore, no strong association of DFS with OS has been established [178]. The ATLAS study, a randomised, double-blind phase III trial including patients receiving (1:1) oral twice-daily axitinib 5 mg or placebo for < 3 years, for a minimum of one year unless patients experienced a recurrence, had a second primary malignancy, significant toxicity, or withdrew consent. The primary endpoint was DFS. A total of 724 patients (363 vs. 361, for axitinib vs. placebo) were randomised. The trial was stopped due to futility at a pre-planned interim analysis at 203 DFS events. There was no significant difference in DFS per independent review committee (IRC) (HR: 0.870, 95% CI: 0.660–1.147, p = 0.3211). Overall survival data were not mature. Similar AEs (99% vs. 92%) and serious AEs (19% vs. 14%), but more grade 3/4 AEs (61% vs. 30%) were reported for axitinib vs. placebo [179]. In contrast, the S-TRAC study included 615 patients randomised to either sunitinib or placebo [180]. The results showed a benefit of sunitinib over placebo for DFS (HR: 0.76, 95% CI: 0.59–0.98, p = 0.03). Grade 3/4 toxicity in the study was 60.5% for patients receiving sunitinib, which translated into significant differences in QoL for loss of appetite and diarrhoea [181]. The study published its updated results in 2018; the results for DFS had not changed significantly (HR: 0.74, 95% CI: 0.55–0.99, p = 0.04) and median OS was not reached in either arm (HR: 0.92, 95% CI: 0.66–1.28, p = 0.6) [181]. The last trial being reported is the SORCE RCT which investigated one and three years of adjuvant sorafenib and which also included patients with non-clear cell subtypes [182]. In SORCE no differences in DFS or OS for patients with high risk of recurrence, or patients with ccRCC only was found. Median DFS was not reached for three years of sorafenib or for placebo (HR: 1.01, 95% CI: 0.83–1.23; p = 0.95), and OS was different (HR: 1.06, 95% CI: 0.82–1.38; p = 0.638). More than half of participants stopped treatment by twelve months. Adverse event rates grade > 3 were 58.6% and 63.9% receiving one year or three years of sorafenib [182]. To date, the results of one RCT on the role of adjuvant everolimus (EVEREST) in patients with RCC is still unpublished. A recent meta-analysis of phase III randomised clinical trials on adjuvant TKIs in ccRCC was published [183]. In the overall population, the pooled HR of OS and DFS was 0.89 (95% CI: 0.76–1.04) and 0.84 (95% CI: 0.76–0.93), respectively. In the low- and high-risk populations, the pooled DFS HR was 0.98 (95% CI: 0.82–1.17) and 0.85 (95% CI: 0.75–0.97), respectively. Adjuvant use of TKIs does not appear to provide a statistically significant OS benefit. However, a benefit in DFS has been observed in overall and high-risk populations, suggesting that better selection of patients might be important for the evaluation of adjuvant therapies in RCC, although these results must be balanced against significant toxicity. In summary, there is currently a lack of proven benefits of adjuvant therapy with VEGFR-TKIs for patients with high-risk RCC after nephrectomy. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has not approved sunitinib for adjuvant treatment of high-risk RCC in adult patients after nephrectomy. Immune checkpoint inhibitors, designed to restore and enhance immune activity against cancer cells, have shown impressive efficacy in the metastatic setting. Several trials have tested these agents in metastatic RCC, leading to a still-ongoing revolution in the treatment pathway. The inclusion of these drugs in clinical practice has led to a third generation of adjuvant studies on ICIs. These include the programmed death receptor-1 inhibitors nivolumab (PROSPER; NCT03055013), pembrolizumab (KEYNOTE-564; NCT03142334), as well as the programmed death ligand-1 inhibitors atezolizumab (IMmotion010; NCT03024996) and durvalumab (RAMPART [Renal Adjuvant MultiPle Arm Randomised Trial]; NCT03288532). Recruitment for most of these studies is still ongoing and except for KEYNOTE-564, results are awaited as of 2022-2023. The Keynote-564 trial is the first trial to report positive primary endpoint data on DFS [184]. Keynote-564 evaluated pembrolizumab (17 cycles of 3-weekly therapy) vs. placebo as adjuvant therapy for 994 patients with intermediate (pT2, grade 4 or sarcomatoid, N0 M0; or pT3, any grade, N0, M0) or high risk (pT4, any grade, N0 M0; or pT any stage, and grade, or N+, M0), or M1 [no evidence of disease (NED) after primary tumour plus soft tissue metastases completely resected < one year from nephrectomy] disease. The median follow-up, defined as time from randomisation to data cut-off, was 24.1 months. The primary endpoint of DFS per investigator assessment was significantly improved in the pembrolizumab group vs. placebo (HR: 0.68, 95% CI: 0.530.87, p = 0.001). The estimated 24-month DFS rate was 77% vs. 68% for pembrolizumab and placebo, respectively. Benefit occurred across broad subgroups of patients including those with M1/NED disease post-surgery (n = 58 [6%]). Investigator assessed DFS was considered preferable to DFS by central review due to its clinical applicability. Overall survival showed a non-statistically significant trend towards a benefit in the pembrolizumab arm (HR: 0.54, 95% CI: 0.30-0.96, p = 0.0164). Follow-up was short and few OS events occurred (two-year OS rate of 97% [pembrolizumab] vs. 94% [placebo]). Grade 3-5 all-cause AEs occurred in 32% vs. 18% of patients for pembrolizumab and placebo, respectively. Quality of life assessment by FKSI-DRS and QLQ30 did not show a statistically significant or clinically meaningful deterioration in health-related QoL or symptom scores for either adjuvant pembrolizumab or placebo. After GRADE assessment the EAU Guidelines 2022 Panel members reached consensus and issued a weak recommendation for adjuvant pembrolizumab for patients with high-risk (defined as per study) operable ccRCC until final OS data are available [185]. Although the guidelines previously did not recommend sunitinib despite positive DFS data in the absence of OS benefit [181, 180, 186], the EAU Guidelines 2022 Panel decided for adjuvant pembrolizumab for the following reasons:

• Immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy has a different mode of action than VEGFR-TKI resulting in complete responses in up to 16% of patients in PD-1 unselected populations in metastatic disease [187]. Despite immature OS data with the early OS signal potentially driven by the M1 population the EAU Guidelines 2022 Panel cannot exclude that a survival benefit will emerge. This was not the case in the adjuvant sunitinib trial (STRAC) [181, 184].

• Pembrolizumab is better tolerated than sunitinib and does not lead to a decline of QoL compared to placebo as did sunitinib [184, 188].

• A number of adjuvants VEGFR trials failed to show a DFS advantage for sunitinib or other VEFGR inhibitors resulting in a negative meta-analysis [189]. The Panel of EAU Guidelines edition 2022 considered the following cautionary points in their decision leading to a weak recommendation:

• A high proportion of patients, cured by surgery, are receiving unnecessary, and potentially harmful treatment.

• The tolerability profile is acceptable but grade 3-5 AEs were higher with 14.7% in the pembrolizumab arm as in the placebo arm (occurring in approximately one-third of patients, all cause). Approximately 18% of patients required treatment discontinuation early for AEs which gives a broad indicator of tolerability. Endocrine AEs may require life-long therapy.

• Other ICI trials have not yet reported and are not available for meta-analysis.

• Biomarker analysis to predict outcome and AEs are not available.

• Final OS data are not yet available.

Table 1: Updated EAU RCC guideline recommendation for the adjuvant treatment of high-risk ccRCC

References:

- MacLennan, S., et al. Systematic review of perioperative and quality-of-life outcomes following surgical management of localised renal cancer. Eur Urol, 2012. 62: 1097. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22841673/

- Kunath, F., et al. Partial nephrectomy versus radical nephrectomy for clinical localised renal masses. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2017. 5: Cd012045. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28485814/

- Van Poppel, H., et al. A prospective, randomised EORTC intergroup phase 3 study comparing the oncologic outcome of elective nephron-sparing surgery and radical nephrectomy for low-stage renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol, 2011. 59: 543. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21186077/

- Thompson, R.H., et al. Radical nephrectomy for pT1a renal masses may be associated with decreased overall survival compared with partial nephrectomy. J Urol, 2008. 179: 468. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18076931/

- Huang, W.C., et al. Partial nephrectomy versus radical nephrectomy in patients with small renal tumors–is there a difference in mortality and cardiovascular outcomes? J Urol, 2009. 181: 55. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19012918/

- Miller, D.C., et al. Renal and cardiovascular morbidity after partial or radical nephrectomy. Cancer, 2008. 112: 511. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18072263/

- Capitanio, U., et al. Nephron-sparing techniques independently decrease the risk of cardiovascular events relative to radical nephrectomy in patients with a T1a-T1b renal mass and normal preoperative renal function. Eur Urol, 2015. 67: 683. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25282367/

- Scosyrev, E., et al. Renal function after nephron-sparing surgery versus radical nephrectomy: results from EORTC randomized trial 30904. Eur Urol, 2014. 65: 372. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23850254/

- Kates, M., et al. Increased risk of overall and cardiovascular mortality after radical nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma 2 cm or less. J Urol, 2011. 186: 1247. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21849201/

- Thompson, R.H., et al. Comparison of partial nephrectomy and percutaneous ablation for cT1 renal masses. Eur Urol, 2015. 67: 252. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25108580/

- Sun, M., et al. Management of localized kidney cancer: calculating cancer-specific mortality and competing risks of death for surgery and nonsurgical management. Eur Urol, 2014. 65: 235. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23567066/

- Sun, M., et al. Comparison of partial vs radical nephrectomy with regard to other-cause mortality in T1 renal cell carcinoma among patients aged >/=75 years with multiple comorbidities. BJU Int, 2013. 111: 67. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22612472/

- Shuch, B., et al. Overall survival advantage with partial nephrectomy: a bias of observational data? Cancer, 2013. 119: 2981. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23674264/

- Lane, B.R., et al. Survival and Functional Stability in Chronic Kidney Disease Due to Surgical Removal of Nephrons: Importance of the New Baseline Glomerular Filtration Rate. Eur Urol, 2015. 68: 996. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26012710/

- Huang, W.C., et al. Chronic kidney disease after nephrectomy in patients with renal cortical tumours: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol, 2006. 7: 735. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16945768/

- Van Poppel, H., et al. A prospective randomized EORTC intergroup phase 3 study comparing the complications of elective nephron-sparing surgery and radical nephrectomy for low-stage renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol, 2007. 51: 1606. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17140723/

- Poulakis, V., et al. Quality of life after surgery for localized renal cell carcinoma: comparison between radical nephrectomy and nephron-sparing surgery. Urology, 2003. 62: 814. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14624900/

- Mir, M.C., et al. Partial Nephrectomy Versus Radical Nephrectomy for Clinical T1b and T2 Renal Tumors: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Comparative Studies. Eur Urol, 2017. 71: 606. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27614693/

- Janssen, M.W.W., et al. Survival outcomes in patients with large (>/=7cm) clear cell renal cell carcinomas treated with nephron-sparing surgery versus radical nephrectomy: Results of a multicenter cohort with long-term follow-up. PLoS One, 2018. 13: e0196427. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29723225/

- Patel, S.H., et al. Oncologic and Functional Outcomes of Radical and Partial Nephrectomy in pT3a Pathologically Upstaged Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Multi-institutional Analysis. Clin Genitourin Cancer, 2020. 18: e723. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32600941/

- Shah, P.H., et al. Partial Nephrectomy is Associated with Higher Risk of Relapse Compared with Radical Nephrectomy for Clinical Stage T1 Renal Cell Carcinoma Pathologically Up Staged to T3a. J Urol, 2017. 198: 289. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28274620/

- Liu, H., et al. A meta-analysis for comparison of partial nephrectomy vs. radical nephrectomy in patients with pT3a renal cell carcinoma. Transl Androl Urol, 2021. 10: 1170. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33850752/

- Lane, B.R., et al. Management of the adrenal gland during partial nephrectomy. J Urol, 2009. 181: 2430. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19371896/

- Bekema, H.J., et al. Systematic review of adrenalectomy and lymph node dissection in locally advanced renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol, 2013. 64: 799. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23643550/

- Blom, J.H., et al. Radical nephrectomy with and without lymph-node dissection: final results of European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) randomized phase 3 trial 30881. Eur Urol, 2009. 55: 28. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18848382/

- Capitanio, U., et al. Lymph node dissection in renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol, 2011. 60: 1212. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21940096/

- Gershman, B., et al. Radical Nephrectomy with or without Lymph Node Dissection for High Risk Nonmetastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Multi-Institutional Analysis. J Urol, 2018. 199: 1143. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29225056/

- Kim S, et al. The relationship of lymph node dissection with recurrence and survival for patients treated with nephrectomy for high-risk renal cell carcinoma. J Urol, 2012. 187: e233. https://www.auajournals.org/doi/10.1016/j.juro.2012.02.649

- Dimashkieh, H.H., et al. Extranodal extension in regional lymph nodes is associated with outcome in patients with renal cell carcinoma. J Urol, 2006. 176: 1978. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17070225/

- Terrone, C., et al. Reassessing the current TNM lymph node staging for renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol, 2006. 49: 324. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16386352/

- Whitson, J.M., et al. Lymphadenectomy improves survival of patients with renal cell carcinoma and nodal metastases. J Urol, 2011. 185: 1615. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21419453/

- Capitanio, U., et al. Extent of lymph node dissection at nephrectomy affects cancer-specific survival and metastatic progression in specific sub-categories of patients with renal cell carcinoma (RCC). BJU Int, 2014. 114: 210. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24854206/

- Gershman, B., et al. Perioperative Morbidity of Lymph Node Dissection for Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Propensity Score-based Analysis. Eur Urol, 2018. 73: 469. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29132713/

- Herrlinger, A., et al. What are the benefits of extended dissection of the regional renal lymph nodes in the therapy of renal cell carcinoma. J Urol, 1991. 146: 1224. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1942267/

- Chapin, B.F., et al. The role of lymph node dissection in renal cell carcinoma. Int J Clin Oncol, 2011. 16: 186. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21523561/

- Kwon, T., et al. Reassessment of renal cell carcinoma lymph node staging: analysis of patterns of progression. Urology, 2011. 77: 373. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20817274/

- Bex, A., et al. Intraoperative sentinel node identification and sampling in clinically node-negative renal cell carcinoma: initial experience in 20 patients. World J Urol, 2011. 29: 793. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21107845/

- Sherif, A.M., et al. Sentinel node detection in renal cell carcinoma. A feasibility study for detection of tumour-draining lymph nodes. BJU Int, 2012. 109: 1134. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21883833/

- May, M., et al. Pre-operative renal arterial embolisation does not provide survival benefit in patients with radical nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma. Br J Radiol, 2009. 82: 724. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19255117/

- Subramanian, V.S., et al. Utility of preoperative renal artery embolization for management of renal tumors with inferior vena caval thrombi. Urology, 2009. 74: 154. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19428069/

- Maxwell, N.J., et al. Renal artery embolisation in the palliative treatment of renal carcinoma. Br J Radiol, 2007. 80: 96. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17495058/

- Lamb, G.W., et al. Management of renal masses in patients medically unsuitable for nephrectomy-natural history, complications, and outcome. Urology, 2004. 64: 909. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15533476/

- Brewer, K., et al. Perioperative and renal function outcomes of minimally invasive partial nephrectomy for T1b and T2a kidney tumors. J Endourol, 2012. 26: 244. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22192099/

- Sprenkle, P.C., et al. Comparison of open and minimally invasive partial nephrectomy for renal tumors 4-7 centimeters. Eur Urol, 2012. 61: 593. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22154728/

- Peng B,et al. Retroperitoneal laparoscopic nephrectomy and open nephrectomy for radical treatment of renal cell carcinoma: A comparison of clinical outcomes. Acad J Sec Military Med Univ, 2006: 1167. https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/portal/resource/pt/wpr-841262

- Steinberg, A.P., et al. Laparoscopic radical nephrectomy for large (greater than 7 cm, T2) renal tumors. J Urol, 2004. 172: 2172. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15538225/

- Gratzke, C., et al. Quality of life and perioperative outcomes after retroperitoneoscopic radical nephrectomy (RN), open RN and nephron-sparing surgery in patients with renal cell carcinoma. BJU Int, 2009. 104: 470. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19239445/

- Hemal, A.K., et al. Laparoscopic versus open radical nephrectomy for large renal tumors: a longterm prospective comparison. J Urol, 2007. 177: 862. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17296361/

- Laird, A., et al. Matched pair analysis of laparoscopic versus open radical nephrectomy for the treatment of T3 renal cell carcinoma. World J Urol, 2015. 33: 25. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24647880/

- Patel, P., et al. A Multicentered, Propensity Matched Analysis Comparing Laparoscopic and Open Surgery for pT3a Renal Cell Carcinoma. J Endourol, 2017. 31: 645. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28381117/

- Desai, M.M., et al. Prospective randomized comparison of transperitoneal versus retroperitoneal laparoscopic radical nephrectomy. J Urol, 2005. 173: 38. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15592021/

- Nambirajan, T., et al. Prospective, randomized controlled study: transperitoneal laparoscopic versus retroperitoneoscopic radical nephrectomy. Urology, 2004. 64: 919. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15533478/

- Nadler, R.B., et al. A prospective study of laparoscopic radical nephrectomy for T1 tumors–is transperitoneal, retroperitoneal or hand assisted the best approach? J Urol, 2006. 175: 1230. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16515966/

- Gabr, A.H., et al. Approach and specimen handling do not influence oncological perioperative and long-term outcomes after laparoscopic radical nephrectomy. J Urol, 2009. 182: 874. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19616234/

- Jeong, I.G., et al. Association of Robotic-Assisted vs Laparoscopic Radical Nephrectomy With Perioperative Outcomes and Health Care Costs, 2003 to 2015. JAMA, 2017. 318: 1561. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29067427/

- Li, J., et al. Comparison of Perioperative Outcomes of Robot-Assisted vs. Laparoscopic Radical Nephrectomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Oncol, 2020. 10: 551052. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33072578/

- Asimakopoulos, A.D., et al. Robotic radical nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma: a systematic review. BMC Urol, 2014. 14: 75. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25234265/

- Soga, N., et al. Comparison of radical nephrectomy techniques in one center: minimal incision portless endoscopic surgery versus laparoscopic surgery. Int J Urol, 2008. 15: 1018. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19138194/

- Park Y, et al. Laparoendoscopic single-site radical nephrectomy for localized renal cell carcinoma: comparison with conventional laparoscopic surgery. J Endourol 2009. 23: A19. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20370595/

- Gill, I.S., et al. Comparison of 1,800 laparoscopic and open partial nephrectomies for single renal tumors. J Urol, 2007. 178: 41. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17574056/

- Lane, B.R., et al. 7-year oncological outcomes after laparoscopic and open partial nephrectomy. J Urol, 2010. 183: 473. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20006866/

- Gong, E.M., et al. Comparison of laparoscopic and open partial nephrectomy in clinical T1a renal tumors. J Endourol, 2008. 22: 953. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18363510/

- Marszalek, M., et al. Laparoscopic and open partial nephrectomy: a matched-pair comparison of 200 patients. Eur Urol, 2009. 55: 1171. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19232819/

- Kaneko, G., et al. The benefit of laparoscopic partial nephrectomy in high body mass index patients. Jpn J Clin Oncol, 2012. 42: 619. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22561514/

- Muramaki, M., et al. Prognostic Factors Influencing Postoperative Development of Chronic Kidney Disease in Patients with Small Renal Tumors who Underwent Partial Nephrectomy. Curr Urol, 2013. 6: 129. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24917730/

- Tugcu, V., et al. Transperitoneal versus retroperitoneal laparoscopic partial nephrectomy: initial experience. Arch Ital Urol Androl, 2011. 83: 175. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22670314/

- Minervini, A., et al. Simple enucleation is equivalent to traditional partial nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma: results of a nonrandomized, retrospective, comparative study. J Urol, 2011. 185: 1604. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21419454/

- Bazzi, W.M., et al. Comparison of laparoendoscopic single-site and multiport laparoscopic radical and partial nephrectomy: a prospective, nonrandomized study. Urology, 2012. 80: 1039. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22990064/

- Masson-Lecomte, A., et al. A prospective comparison of the pathologic and surgical outcomes obtained after elective treatment of renal cell carcinoma by open or robot-assisted partial nephrectomy. Urol Oncol, 2013. 31: 924. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21906969/

- Peyronnet, B., et al. Comparison of 1800 Robotic and Open Partial Nephrectomies for Renal Tumors. Ann Surg Oncol, 2016. 23: 4277. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27411552/

- Nisen, H., et al. Hand-assisted laparoscopic versus open partial nephrectomy in patients with T1 renal tumor: Comparative perioperative, functional and oncological outcome. Scand J Urol, 2015: 1. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26317448/

- Chang, K.D., et al. Functional and oncological outcomes of open, laparoscopic and robot-assisted partial nephrectomy: a multicentre comparative matched-pair analyses with a median of 5 years’ follow-up. BJU Int, 2018. 122: 618. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29645344/

- Alimi, Q., et al. Comparison of Short-Term Functional, Oncological, and Perioperative Outcomes Between Laparoscopic and Robotic Partial Nephrectomy Beyond the Learning Curve. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A, 2018. 28: 1047. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29664692/

- Choi, J.E., et al. Comparison of perioperative outcomes between robotic and laparoscopic partial nephrectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Urol, 2015. 67: 891. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25572825/

- Hinata, N., et al. Robot-assisted partial nephrectomy versus standard laparoscopic partial nephrectomy for renal hilar tumor: A prospective multi-institutional study. Int J Urol, 2021. 28: 382. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33368639/

- Arora, S., et al. What is the hospital volume threshold to optimize inpatient complication rate after partial nephrectomy? Urol Oncol, 2018. 36: 339.e17. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29773492/

- Xia, L., et al. Hospital volume and outcomes of robot-assisted partial nephrectomy. BJU Int, 2018. 121: 900. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29232025/

- Peyronnet, B., et al. Impact of hospital volume and surgeon volume on robot-assisted partial nephrectomy outcomes: a multicentre study. BJU Int, 2018. 121: 916. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29504226/

- Schiavina, R., et al. Predicting positive surgical margins in partial nephrectomy: A prospective multicentre observational study (the RECORd 2 project). Eur J Surg Oncol, 2020. 46: 1353. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32007380/

- Shanmugasundaram, S., et al. Preoperative embolization of renal cell carcinoma prior to partial nephrectomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Imaging, 2021. 76: 205. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33964598/

- Tabayoyong, W., et al. Variation in Surgical Margin Status by Surgical Approach among Patients Undergoing Partial Nephrectomy for Small Renal Masses. J Urol, 2015. 194: 1548. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26094808/

- Porpiglia, F., et al. Partial Nephrectomy in Clinical T1b Renal Tumors: Multicenter Comparative Study of Open, Laparoscopic and Robot-assisted Approach (the RECORd Project). Urology, 2016. 89: 45. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26743388/

- Steinestel, J., et al. Positive surgical margins in nephron-sparing surgery: risk factors and therapeutic consequences. World J Surg Oncol, 2014. 12: 252. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25103683/

- Wood, E.L., et al. Local Tumor Bed Recurrence Following Partial Nephrectomy in Patients with Small Renal Masses. J Urol, 2018. 199: 393. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28941919/

- Bensalah, K., et al. Positive surgical margin appears to have negligible impact on survival of renal cell carcinomas treated by nephron-sparing surgery. Eur Urol, 2010. 57: 466. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19359089/

- Lopez-Costea, M.A., et al. Oncological outcomes and prognostic factors after nephron-sparing surgery in renal cell carcinoma. Int Urol Nephrol, 2016. 48: 681. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26861062/

- Shah, P.H., et al. Positive Surgical Margins Increase Risk of Recurrence after Partial Nephrectomy for High Risk Renal Tumors. J Urol, 2016. 196: 327. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26907508/

- Tellini, R., et al. Positive Surgical Margins Predict Progression-free Survival After Nephron-sparing Surgery for Renal Cell Carcinoma: Results From a Single Center Cohort of 459 Cases With a Minimum Follow-up of 5 Years. Clin Genitourin Cancer, 2019. 17: e26. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30266249/

- Ryan, S.T., et al. Impact of positive surgical margins on survival after partial nephrectomy in localized kidney cancer: analysis of the National Cancer Database. Minerva Urol Nephrol, 2021. 73: 233. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32748614/

- Sundaram, V., et al. Positive margin during partial nephrectomy: does cancer remain in the renal remnant? Urology, 2011. 77: 1400. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21411126/

- Kim, S.P., et al. Treatment of Patients with Positive Margins after Partial Nephrectomy. J Urol, 2016. 196: 301. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27188474/

- Antic, T., et al. Partial nephrectomy for renal tumors: lack of correlation between margin status and local recurrence. Am J Clin Pathol, 2015. 143: 645. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25873497/

- Zini, L., et al. A population-based comparison of survival after nephrectomy vs nonsurgical management for small renal masses. BJU Int, 2009. 103: 899. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19154499/

- Xing, M., et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Thermal Ablation, Surgical Resection, and Active Surveillance for T1a Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)Medicare-linked Population Study. Radiology, 2018. 288: 81. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29737950/

- Sun, M., et al. 1634 Management of localized kidney cancer: calculating cancer-specific mortality and competing-risks of death tradeoffs between surgery and acive surveillance. J Urol, 2013. 189: e672. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022534713033764

- Huang W.C., et al. Surveillance for the management of small renal masses: outcomes in a population-based cohort. J Urol, 2013: e483. https://ascopubs.org/doi/abs/10.1200/jco.2013.31.6_suppl.343

- Hyams E.S., et al. Partial nephrectomy vs. Non-surgical management for small renal massess: a population-based comparison of disease-specific and overall survival. J Urol, 2012. 187: E678. https://www.jurology.com/article/S0022-5347(12)01914-3/abstract

- Lane, B.R., et al. Active treatment of localized renal tumors may not impact overall survival in patients aged 75 years or older. Cancer, 2010. 116: 3119. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20564627/

- Hollingsworth, J.M., et al. Five-year survival after surgical treatment for kidney cancer: a populationbased competing risk analysis. Cancer, 2007. 109: 1763. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17351954/

- Volpe, A., et al. The natural history of incidentally detected small renal masses. Cancer, 2004. 100: 738. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14770429/

- Jewett, M.A., et al. Active surveillance of small renal masses: progression patterns of early stage kidney cancer. Eur Urol, 2011. 60: 39. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21477920/

- Smaldone, M.C., et al. Small renal masses progressing to metastases under active surveillance: a systematic review and pooled analysis. Cancer, 2012. 118: 997. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21766302/

- Patel, N., et al. Active surveillance of small renal masses offers short-term oncological efficacy equivalent to radical and partial nephrectomy. BJU Int, 2012. 110: 1270. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22564495/

- Pierorazio, P.M., et al. Five-year analysis of a multi-institutional prospective clinical trial of delayed intervention and surveillance for small renal masses: the DISSRM registry. Eur Urol, 2015. 68: 408. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25698065/

- Uzosike, A.C., et al. Growth Kinetics of Small Renal Masses on Active Surveillance: Variability and Results from the DISSRM Registry. J Urol, 2018. 199: 641. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28951284/

- Abou Youssif, T., et al. Active surveillance for selected patients with renal masses: updated results with long-term follow-up. Cancer, 2007. 110: 1010. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17628489/

- Abouassaly, R., et al. Active surveillance of renal masses in elderly patients. J Urol, 2008. 180: 505. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18550113/

- Crispen, P.L., et al. Natural history, growth kinetics, and outcomes of untreated clinically localized renal tumors under active surveillance. Cancer, 2009. 115: 2844. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19402168/

- Rosales, J.C., et al. Active surveillance for renal cortical neoplasms. J Urol, 2010. 183: 1698. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20299038/

- Pierorazio P., et al. Quality of life on active surveillance for small masses versus immediate intervention: interim analysis of the DISSRM (delayed intervention and surveillance for small renal masses) registry. J Urol, 2013. 189: e259. https://www.auajournals.org/doi/full/10.1016/j.juro.2013.02.185

- Finelli, A., et al. Small Renal Mass Surveillance: Histology-specific Growth Rates in a Biopsycharacterized Cohort. Eur Urol, 2020. 78: 460. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32680677/

- Atwell, T.D., et al. Percutaneous ablation of renal masses measuring 3.0 cm and smaller: comparative local control and complications after radiofrequency ablation and cryoablation. AJR Am J Roentgenol, 2013. 200: 461. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23345372/

- Widdershoven, C.V., et al. Renal biopsies performed before versus during ablation of T1 renal tumors: implications for prevention of overtreatment and follow-up. Abdom Radiol (NY), 2020. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32564209/

- Lay, A.H., et al. Oncologic Efficacy of Radio Frequency Ablation for Small Renal Masses: Clear Cell vs Papillary Subtype. J Urol, 2015. 194: 653. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25846416/

- McClure, T., et al. Efficacy of percutaneous radiofrequency ablation may vary with clear cell renal cell cancer histologic subtype. Abdom Radiol (NY), 2018. 43: 1472. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28936542/

- Liu, N., et al. Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation for renal cell carcinoma vs. partial nephrectomy: Comparison of long-term oncologic outcomes in both clear cell and non-clear cell of the most common subtype. Urol Oncol, 2017. 35: 530.e1. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28408296/

- Breen, D.J., et al. Image-guided Cryoablation for Sporadic Renal Cell Carcinoma: Three- and 5-year Outcomes in 220 Patients with Biopsy-proven Renal Cell Carcinoma. Radiology, 2018. 289: 554. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30084744/

- Sisul, D.M., et al. RENAL nephrometry score is associated with complications after renal cryoablation: a multicenter analysis. Urology, 2013. 81: 775. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23434099/

- Kim E.H., et al. Outcomes of laparoscopic and percutaneous cryoablation for renal masses. J Urol, 2013. 189: e492. https://www.auajournals.org/doi/10.1016/j.juro.2013.02.2554

- Goyal, J., et al. Single-center comparative oncologic outcomes of surgical and percutaneous cryoablation for treatment of renal tumors. J Endourol, 2012. 26: 1413. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22642574/

- Jiang, K., et al. Laparoscopic cryoablation vs. percutaneous cryoablation for treatment of small renal masses: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget, 2017. 8: 27635. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28199973/

- Zargar, H., et al. Cryoablation for Small Renal Masses: Selection Criteria, Complications, and Functional and Oncologic Results. Eur Urol, 2016. 69: 116. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25819723/

- Pickersgill, N.A., et al. Ten-Year Experience with Percutaneous Cryoablation of Renal Tumors: Tumor Size Predicts Disease Progression. J Endourol, 2020. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32292059/

- Morkos, J., et al. Percutaneous Cryoablation for Stage 1 Renal Cell Carcinoma: Outcomes from a 10-year Prospective Study and Comparison with Matched Cohorts from the National Cancer Database. Radiology, 2020. 296: 452. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32515677/

- Hebbadj, S., et al. Safety Considerations and Local Tumor Control Following Percutaneous ImageGuided Cryoablation of T1b Renal Tumors. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol, 2018. 41: 449. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29075877/

- Grange, R., et al. Computed tomography-guided percutaneous cryoablation of T1b renal tumors: safety, functional and oncological outcomes. Int J Hyperthermia, 2019. 36: 1065. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31648584/

- Pecoraro, A., et al. Cryoablation Predisposes to Higher Cancer Specific Mortality Relative to Partial Nephrectomy in Patients with Nonmetastatic pT1b Kidney Cancer. J Urol, 2019. 202: 1120. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31347950/

- Andrews, J.R., et al. Oncologic Outcomes Following Partial Nephrectomy and Percutaneous Ablation for cT1 Renal Masses. Eur Urol, 2019. 76: 244. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31060824/

- Sundelin, M.O., et al. Repeated Cryoablation as Treatment Modality after Failure of Primary Renal Cryoablation: A European Registry for Renal Cryoablation Multinational Analysis. J Endourol, 2019. 33: 909. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31507206/

- Lian, H., et al. Single-center comparison of complications in laparoscopic and percutaneous radiofrequency ablation with ultrasound guidance for renal tumors. Urology, 2012. 80: 119. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22633890/