Renal Cell Carcinoma

Part 3

Comprehensive Review Article

Prof. Dr. Semir. A. Salim. Al Samarrai

Advanced/metastatic RCC:

- Local therapy of advanced/metastatic RCC

- Cytoreductive nephrectomy

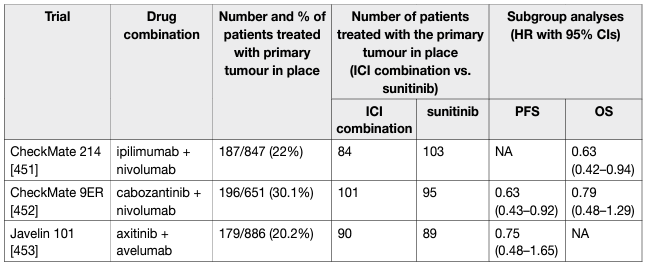

Tumour resection is potentially curative only if all tumour deposits are excised. This includes patients with the primary tumour in place and single- or oligometastatic resectable disease. For most patients with metastatic disease, cytoreductive nephrectomy (CN) is palliative and systemic treatments are necessary. In a combined analysis of two RCTs comparing CN+ IFN-based immunotherapy vs. IFN-based immunotherapy only, increased long-term survival was found in patients treated with CN [1]. However, IFN-based immunotherapy is no longer relevant in contemporary clinical practice. In order to investigate the role and sequence of CN in the era of targeted therapy, a structured literature assessment was performed to identify relevant RCTs and systematic reviews published between July 1st – June 30th 2019. Two RCTs [2,3] and a narrative systematic review were identified [4]. The narrative systematic review included both RCTs and ten non-randomised studies. CARMENA, a phase III non-inferiority RCT investigating immediate CN followed by sunitinib vs. sunitinib alone, showed that sunitinib alone was not inferior to CN followed by sunitinib with regard to OS [5]. The trial included 450 patients with metastatic ccRCC of intermediate- and MSKCC poor-risk of whom 226 were randomised to immediate CN followed by sunitinib and 224 to sunitinib alone. Patients in both arms had a median of two metastatic sites. Patients in both arms had a tumour burden of a median/mean of 140 mL of measurable disease by Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumours (RECIST) 1.1, of which 80 mL accounted for the primary tumour. The study did not reach the full accrual of 576 patients and the Independent Data Monitoring Commission (IDMC) advised the trial steering committee to close the study. In an ITT analysis after a median follow-up of 50.9 months, median OS with CN was 13.9 months vs. 18.4 months with sunitinib alone (HR: 0.89, 95% CI: 0.71–1.10). This was found in both risk groups. For MSKCC intermediate-risk patients (n = 256) median OS was 19.0 months with CN and 23.4 months with sunitinib alone (HR: 0.92, 95% CI: 0.60–1.24) and for MSKCC poor risk (n = 193) 10.2 months and 13.3 months, respectively (HR: 0.86, 95% CI: 0.62–1.17). Non-inferiority was also found in two per-protocol analyses accounting for patients in the CN arm who either did not undergo surgery (n = 16) or did not receive sunitinib (n = 40), and patients in the sunitinib-only arm who did not receive the study drug (n = 11). Median PFS in the ITT population was 7.2 months with CN and 8.3 months with sunitinib alone (HR: 0.82, 95% CI: 0.67–1.00). The clinical benefit rate, defined as disease control beyond twelve weeks was 36.6% with CN and 47.9% with sunitinib alone (p = 0.022). Of note, 38 patients in the sunitinib-only arm required secondary CN due to acute symptoms or for complete or near-complete response. The median time from randomisation to secondary CN was 11.1 months. The randomised EORTC SURTIME study revealed that the sequence of CN and sunitinib did not affect PFS (HR: 0.88, 95% CI: 0.59–1.37, p = 0.569). The trial accrued poorly and therefore results are mainly exploratory. However, in secondary endpoint analysis a strong OS benefit was observed in favour of the deferred CN approach in the ITT population with a median OS of 32.4 (range 14.5–65.3) months in the deferred CN arm vs. 15.0 (9.3–29.5) months in the immediate CN arm (HR: 0.57, 95% CI: 0.34–0.95, p = 0.032). The deferred CN approach appears to select out patients with inherent resistance to systemic therapy [6]. This confirms previous findings from single-arm phase II studies [4,7]. Moreover, deferred CN and surgery appear safe after sunitinib which supports the findings, with some caution, of the only available RCT. In patients with poor PS or IMDC poor risk, small primaries and high metastatic volume and/or a sarcomatoid tumour, CN is not recommended [8]. These data are confirmed by CARMENA [5] and upfront pre-surgical VEGFR-targeted therapy followed by CN seems to be beneficial [9]. Meanwhile first-line therapy recommendations for patients with their primary tumour in place have changed to ICI combination therapy with sunitinib and other VEGFR-TKI monotherapies reserved for those who cannot tolerate ICI combination or have no access to these drugs. High-level evidence regarding CN is not available for ICI combinations but up to 30% of patients with primary metastatic disease, treated with their tumour in place, were included in the pivotal ICI combination trials (Table 1). The subgroup HRs, where available, suggest better outcomes for the ICI combination compared to sunitinib monotherapy. In mRCC patients without a need for immediate drug treatment, a recent systematic review evaluating effects of CN demonstrated an OS advantage of CN [4]. These data were supported by a nation-wide registry study showing that patients selected for primary CN had a significant OS advantage across all age groups [10].

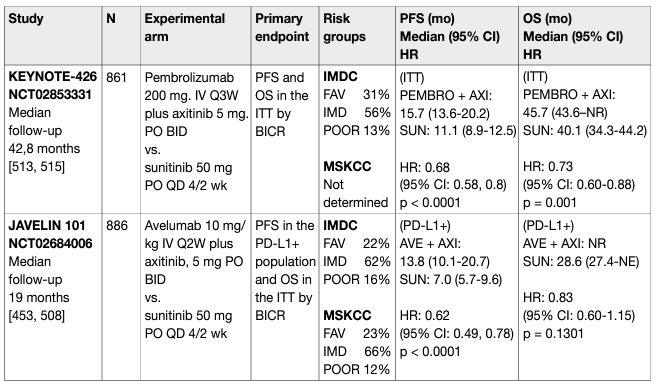

Table 1: Key trials on immune checkpoint inhibitor combinations for primary metastatic disease

The results of CARMENA and SURTIME demonstrated that patients who require systemic therapy benefit from immediate drug treatment. While randomised trials to investigate deferred vs. no cytoreductive nephrectomy with ICI and ICI combinations are ongoing, the exploratory results from the ICI combination trials demonstrate that the respective IO+IO or TKI+IO combinations have a superior effect on the primary tumour and metastatic sites when compared to sunitinib alone (Table 1). In accordance with the CARMENA and SURTIME data this suggests that mRCC patients and IMDC intermediate- and poor-risk groups with their primary tumour in place should be treated with upfront IO-based combinations. In patients with a clinical response to IO-based combinations, a subsequent CN may be considered.

- Embolisation of the primary tumour

In patients unfit for surgery or with non-resectable disease, embolisation can control symptoms including visible haematuria or flank pain [11,12,13].

- Local therapy of metastases in metastatic RCC

A systematic review of the local treatment of metastases from RCC in any organ was undertaken [14]. Interventions included metastasectomy, various radiotherapy modalities, and no local treatment. The outcomes assessed were OS, CSS and PFS, local symptom control and AEs. A risk-of-bias assessment was conducted [15]. Of the 2,235 studies identified only sixteen non-randomised comparative studies were included. Eight studies reported on local therapies of RCC-metastases in various organs [16–23]. This included metastases to any single organ or multiple organs. Three studies reported on local therapies of RCC metastases in bone, including the spine [24–26], two in the brain [27,28] and one each in the liver [29] lung [30] and pancreas [31]. Three studies were published as abstracts only [19, 21, 30]. Data were too heterogeneous to meta-analyse. There was considerable variation in the type and distribution of systemic therapies (cytokines and VEGF-inhibitors) and in reporting the results.

- Complete versus no/incomplete metastasectomy

A systematic review, including only eight studies, compared complete vs. no and/or incomplete metastasectomy of RCC metastases in various organs [16–23]. In one study complete resection was achieved in only 45% of the metastasectomy cohort, which was compared with no metastasectomy [23]. Non-surgical modalities were not applied. Six studies [17–19, 21–23] reported a significantly longer median OS or CSS following complete metastasectomy (the median value for OS or CSS was 40.75 months, range 23–122 months) compared with incomplete and/or no metastasectomy (the median value for OS or CSS was 14.8 months, range 8.4–55.5 months). Of the two remaining studies, one [16] showed no significant difference in CSS between complete and no metastasectomy, and one [20] reported a longer median OS for metastasectomy albeit no p-value was provided. Three studies reported on treatment of RCC metastases in the lung [30], liver [29], and pancreas [31], respectively. The lung study reported a significantly higher median OS for metastasectomy vs. medical therapy only for both targeted therapy and immunotherapy. Similarly, the liver and pancreas study reported a significantly higher median OS and five-year OS for metastasectomy vs. no metastasectomy.

- Local therapies for RCC bone metastases

Of the three studies identified, one compared single-dose image-guided radiotherapy (IGRT) with hypofractionated IGRT in patients with RCC bone metastases [26]. Single-dose IGRT (> 24 Gy) had a significantly better three-year actuarial local PFS rate, also shown by Cox regression analysis. Another study compared metastasectomy/curettage and local stabilisation with no surgery of solitary RCC bone metastases in various locations [24]. A significantly higher five-year CSS rate was observed in the intervention group. After adjusting for prior nephrectomy, gender and age, multi-variable analysis still favoured metastasectomy/ curettage and stabilisation. A third study compared the efficacy and durability of pain relief between singledose stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) and conventional radiotherapy in patients with RCC bone metastases to the spine [25]. Pain, ORR, time-to-pain relief and duration of pain relief were similar.

- Local therapies for RCC brain metastases

Two studies on RCC brain metastases were included. A three-armed study compared stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) vs. whole brain radiotherapy (WBRT) vs. SRS and WBRT [27]. Each group was further subdivided into recursive partitioning analysis (RPA) classes I to III (I favourable, II moderate and III poor patient status). Twoyear OS and intra-cerebral control were equivalent in patients treated with SRS alone and SRS plus WBRT. Both treatments were superior to WBRT alone in the general study population and in the RPA subgroup analyses. A comparison of SRS vs. SRS and WBRT in a subgroup analysis of RPA class I showed significantly better two-year OS and intra-cerebral control for SRS plus WBRT based on only three participants. The other study compared fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy (FSRT) with metastasectomy and conventional radiotherapy or conventional radiotherapy alone [28]. Several patients in all groups underwent alternative surgical and non-surgical treatments after initial treatment. One-, two- and three-year survival rates were higher but not significantly so for FSRT as for metastasectomy and conventional radiotherapy, or conventional radiotherapy alone. Fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy did not result in a significantly better two-year local control rate compared with metastasectomy plus conventional radiotherapy.

- Embolisation of metastases

Embolisation prior to resection of hypervascular bone or spinal metastases can reduce intra-operative blood loss [32]. In selected patients with painful bone or paravertebral metastases, embolisation can relieve symptoms [33].

- Adjuvant treatment in cM0 patients after metastasectomy

Patients after metastasectomy and no evidence of disease (cM0) have a high risk of relapse. Recent attempts to reduce RFS by offering adjuvant TKI treatment after metastasectomy did not demonstrate an improvement in RFS. In a recent phase II trial 129 patients were randomised to either pazopanib 800 mg daily vs. placebo for 52 weeks. The primary study endpoint of a 42% DFS improvement from 25% to 45% at three years was not met. Hazard ratio for DFS in pazopanib vs. placebo-treated patients was 0.85 (0.55–1.31), p = 0.47 [34]. A second phase II trial randomised 69 ccRCC patients after metastasectomy and no evidence of disease to either sorafenib (400 mg twice daily) or observation. The study was terminated early due to slow accrual and the availability of new agents and multimodal treatment options, including surgery or a locoregional approach. The primary endpoint of RFS was not reached with a RFS of 21 months in the sorafenib arms vs. 37 months in the observation arm (p = 0.404) [35].

Results for single-agent pembrolizumab post-surgery for metastatic disease are therefore difficult to interpret due to the small subgroup. Nevertheless, the DFS HR of 0.29 (95% CI: 0.12-0.69) in favour of resection of M1 to NED plus pembrolizumab shows that patients with subclinical, but progressive disease who were subjected to metastasectomy had a benefit of adjuvant systemic therapy with pembrolizumab. Based on the current data it cannot be concluded that for patients with oligo-progressive disease, metastasectomy within the first year of initial diagnosis of the primary and subsequent adjuvant pembrolizumab is superior to a period of observation and dual IO based combination first-line therapy upon progression. Data from the TKI era suggest that patients with oligometastatic disease recurrence can be observed for up to a median of sixteen months before systemic therapy is required and that this practice is common in real-world settings (30%) [36, 37]. In addition, it is possible that metastatectomy may lead to poorer outcomes compared to systemic therapy approaches as a relapse within the first twelve months and presentation with synchronous (oligo-) metastatic disease is attributed to the IMDC intermediate risk-group. The Panel of EAU Guidelines edition 2022 therefore does not encourage metastasectomy and adjuvant pembrolizumab in this advanced population with recurrent disease within one year after primary surgery. A careful reassessment of disease status to rule out rapid progressive disease should be performed. Data from other adjuvant ICI studies including M1 NED subgroups may clarify this issue further (IMmotion010, NCT03024996).

Systemic therapy for advanced/metastatic RCC:

- Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy has proven to be generally ineffective in the treatment of RCC but can be offered in rare patients, with the exception of collecting duct and medullary carcinoma [38].

- Targeted therapies

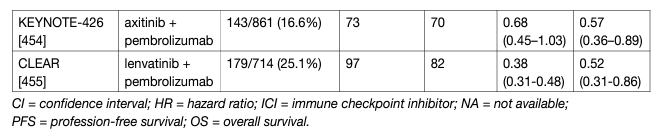

In sporadic ccRCC, hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) accumulation due to VHL-inactivation results in overexpression of VEGF and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), which promote neo-angiogenesis [39-41]. This process substantially contributes to the development and progression of RCC. Several targeting drugs for the treatment of mRCC are approved in both the USA and Europe. Most published trials have selected for clear-cell carcinoma subtypes, thus no robust evidencebased recommendations can be given for non-ccRCC subtypes. In major trials leading to registration of the approved targeted agents, patients were stratified according to the IMDC risk model (Table 2) [42].

Table 2: Median OS and percentage of patients surviving two years treated in the era of targeted therapy per IMDC risk group*

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors:

- Sorafenib

Sorafenib is an oral multi-kinase inhibitor. A trial compared sorafenib and placebo after failure of prior systemic immunotherapy or in patients unfit for immunotherapy. Sorafenib improved PFS (HR: 0.44, 95% CI: 0.35–0.55, p < 0.01) [43]. Overall survival improved in patients initially assigned to placebo who were censored at crossover [44]. In patients with previously untreated mRCC sorafenib was not superior to IFN-α (phase II study). A number of studies have used sorafenib as the control arm in sunitinib-refractory disease vs. axitinib, dovitinib or temsirolimus. None showed superior survival for the study drug compared to sorafenib.

- Sunitinib

Sunitinib is an oral TKI inhibitor and has anti-tumour and anti-angiogenic activity. First-line monotherapy with sunitinib demonstrated significantly longer PFS compared with IFN-α. Overall survival was greater in patients treated with sunitinib (26.4 months) vs. IFN-α (21.8 months) despite crossover [45]. In the EFFECT trial, sunitinib 50 mg/day (four weeks on/two weeks off) was compared with continuous uninterrupted sunitinib 37.5 mg/day in patients with cc-mRCC [46]. No significant differences in OS were seen (23.1 vs. 23.5 months, p = 0.615). Toxicity was comparable in both arms. Because of the non-significant, but numerically longer time to progression with the standard 50 mg dosage, the authors recommended using this regimen. Alternate scheduling of sunitinib (two weeks on/one week off) is being used to manage toxicity, but robust data to support its use is lacking [47,48].

- Pazopanib

Pazopanib is an oral angiogenesis inhibitor. In a trial of pazopanib vs. placebo in treatment-naïve mRCC patients and cytokine-treated patients, a significant improvement in PFS and tumour response was observed [49]. A non-inferiority trial comparing pazopanib with sunitinib (COMPARZ) established pazopanib as an alternative to sunitinib. It showed that pazopanib was not associated with significantly worse PFS or OS compared to sunitinib. The two drugs had different toxicity profiles, and QoL was better with pazopanib [50]. In another patient-preference study (PISCES), patients preferred pazopanib to sunitinib (70% vs. 22%, p < 0.05) due to symptomatic toxicity [51]. Both studies were limited in that intermittent therapy (sunitinib) was compared with continuous therapy (pazopanib).

- Axitinib

Axitinib is an oral selective second-generation inhibitor of VEGFR-1, -2, and -3. Axitinib was first evaluated as second-line treatment. In the AXIS trial, axitinib was compared to sorafenib in patients who had previously failed cytokine treatment or targeted agents (mainly sunitinib) [52]. The overall median PFS was greater for axitinib than sorafenib. Axitinib was associated with a greater PFS than sorafenib (4.8 vs. 3.4 months) after progression on sunitinib. Axitinib showed grade 3 diarrhoea in 11%, hypertension in 16%, and fatigue in 11% of patients. Final analysis of OS showed no significant differences between axitinib or sorafenib [53,54]. In a randomised phase III trial of axitinib vs. sorafenib in first-line treatment-naïve cc-mRCC, a significant difference in median PFS between the treatment groups was not demonstrated, although the study was underpowered, raising the possibility of a type II error [55]. As a result of this study, axitinib is not approved for first-line therapy.

- Cabozantinib

Cabozantinib is an oral inhibitor of tyrosine kinase, including MET, VEGF and AXL. Cabozantinib was investigated in a phase I study in patients resistant to VEGFR and mTOR inhibitors demonstrating objective responses and disease control [56]. Based on these results an RCT investigated cabozantinib vs. everolimus in patients with ccRCC failing one or more VEGF-targeted therapies (METEOR) [57, 58]. Cabozantinib delayed PFS compared to everolimus in VEGF-targeted therapy refractory disease (HR: 0.58, 95% CI: 0.45–0.75) [57]. The median OS was 21.4 months (95% CI: 18.7 to not estimable) with cabozantinib and 16.5 months (95% CI: 14.7–18.8) with everolimus in VEGF-resistant RCC. The HR for death was 0.66 (95% CI: 0.53–0.83, p = 0.0003) [58]. Grade 3 or 4 AEs were reported in 74% with cabozantinib and 65% with everolimus. Adverse events were managed with dose reductions; doses were reduced in 60% of the patients who received cabozantinib. The Alliance A031203 CABOSUN randomised phase II trial comparing cabozatinib and sunitinib in first-line in 157 intermediate- and poor-risk patients favoured cabozantinib for RR and PFS, but not OS [59, 60]. Cabozantinib significantly increased median PFS (8.2 vs. 5.6 months, adjusted HR: 0.66, 95% CI: 0.46 to 0.95; one-sided p = 0.012). Objective response rate was 46% (95% CI: 34–57) for cabozantinib vs. 18% (95% CI: 10–28) for sunitinib. All-causality grade 3 or 4 AEs were similar for cabozantinib and sunitinib. No difference in OS was seen. Due to limitations of the statistical analyses within this trial, the evidence is inferior over existing choices.

- Lenvatinib

Lenvatinib is an oral multi-target TKI of VEGFR1, VEGFR2, and VEGFR3, with inhibitory activity against fibroblast growth factor receptors (FGFR1, FGFR2, FGFR3, and FGFR4), platelet growth factor receptor (PDGFR-α), re-arranged during transfection (RET) and receptor for stem cell factor (KIT). It has recently been investigated in a randomised phase II study in combination with everolimus vs. lenvatinib or everolimus alone [61].

- Tivozanib

Tivozanib is a potent and selective TKI of VEGFR1, VEGFR2, and VEGFR3 and was compared in two phase III trials with sorafenib in patients with mRCC [62,63]. Tivozanib was approved by the EMA in front-line mRCC. While it was associated with a PFS advantage in both studies, no OS advantage was seen. In view of the choice of sorafenib as the control arm in the front-line trial, the Panel of EAU Guidelines edition 2022 considers there is too much uncertainty, and too many attractive alternatives, to support its use in this front-line setting.

- Monoclonal VEGF antibody

Bevacizumab is a humanised monoclonal antibody. The double-blind AVOREN study compared bevacizumab plus IFN-α with IFN-α monotherapy in mRCC. Overall response was higher in the bevacizumab plus IFN-α group. Median PFS increased from 5.4 months with IFN-α to 10.2 months with bevacizumab plus IFN-α. No benefit was seen in MSKCC poor-risk patients. Median OS in this trial, which allowed crossover after progression, was not greater in the bevacizumab/IFN-α group (23.3 vs. 21.3 months) [64]. An open-label trial (CALGB 90206) of bevacizumab plus IFN-α vs. IFN-α showed a higher median PFS for the combination group [65,66]. Objective response rate was also higher in the combination group. Overall toxicity was greater for bevacizumab plus IFN-α, with significantly more grade 3 hypertension, anorexia, fatigue, and proteinuria. Bevacizumab, alone, or in combinations, is not widely recommended or used in mRCC due to more attractive alternatives.

mTOR inhibitors 7.4.2.3.1 Temsirolimus Temsirolimus is a specific inhibitor of mTOR [67]. Its use has been superseded as front-line treatment option.

- Everolimus

Everolimus is an oral mTOR inhibitor, which is established in the treatment of VEGF-refractory disease. The RECORD-1 study compared everolimus plus best supportive care (BSC) vs. placebo plus BSC in patients with previously failed anti-VEGFR treatment (or previously intolerant of VEGF-targeted therapy) [68]. The data showed a median PFS of 4 vs. 1.9 months for everolimus and placebo, respectively [68].

The Panel of EAU Guidelines edition 2022 consider, even in the absence of conclusive data, that everolimus may present a therapeutic option in patients who were intolerant to, or previously failed, immune- and VEGFR-targeted therapies. Recent phase II data suggest adding lenvatinib is attractive.

Immunotherapy:

- Immune checkpoint inhibitors

- Immuno-oncology monotherapy

Immune checkpoint inhibitor with monoclonal antibodies targets and blocks the inhibitory T-cell receptor PD-1 or cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4)-signalling to restore tumour-specific T-cell immunity [69]. Immune checkpoint inhibitor monotherapy has been investigated as second- and third-line therapy. A phase III trial of nivolumab vs. everolimus after one or two lines of VEGF-targeted therapy for mRCC with a clear cell component (CheckMate 025, NCT01668784) reported a longer OS, better QoL and fewer grade 3 or 4 AEs with nivolumab than with everolimus [70]. Nivolumab has superior OS to everolimus (HR: 0.73, 95% CI: 0.57–0.93, p < 0.002) in VEGF-refractory RCC with a median OS of 25 months for nivolumab and 19.6 months for everolimus with a five-year OS probability of 26% vs. 18% [71]. Patients who had failed multiple lines of VEGF-targeted therapy were included in this trial making the results broadly applicable. The trial included 15% MSKCC poor-risk patients. There was no PFS advantage with nivolumab despite the OS advantage. Progression-free survival does not appear to be a reliable surrogate of outcome for PD-1 therapy in RCC. Currently PD-L1 biomarkers are not used to select patients for this therapy. There are no RCTs supporting the use of single-agent ICI in treatment-naïve patients. Randomised phase II data for atezolizumab vs. sunitinib showed a HR of 1.19 (95% CI: 0.82–1.71) which did not justify further assessment of atezolizumab as single agent as first-line treatment option in this group of patients, despite high complete response rates in the biomarker-positive population [72]. Single-arm phase II data for pembrolizumab from the KEYNOTE-427 trial show high response rates of 38% (up to 50% in PD-L1+ patients), but a PFS of 8.7 months (95% CI: 6.7–12.2) [72]. Based on these results and in the absence of randomised phase III data, single-agent checkpoint inhibitor therapy is not recommended as an alternative in a first-line therapy setting.

- Immunotherapy/combination therapy

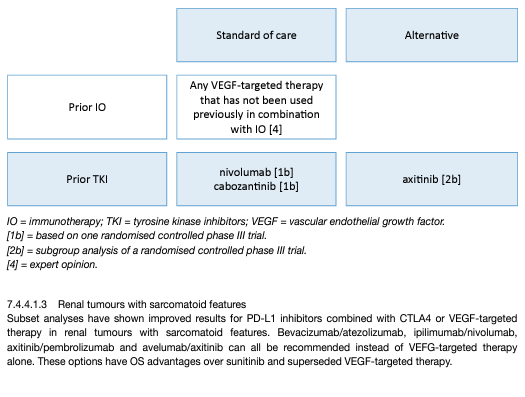

The phase III trial CheckMate 214 (NCT 02231749) showed a superiority of nivolumab and ipilimumab over sunitinib. The primary endpoint population focused on the IMDC intermediate- and poor-risk population where the combination demonstrated an OS benefit (HR: 0.63, 95% CI: 0.44–0.89) which led to regulatory approval [73] and a paradigm shift in the treatment of mRCC [74]. Results from CheckMate 214 further established that the combination of ipilimumab and nivolumab was associated with higher response rates (RR) (39% in the ITT population), complete response rates (8% in the ITT population [central radiology review]) and duration of response compared to sunitinib. Progression-free survival did not achieve the pre-defined endpoint. The exploratory analysis of OS data in the PD-L1-positive population was 0.45 (95% CI: 0.29–0.41). A recent update with 60-month data shows ongoing benefits for the immune combination with independently assessed complete response rates of 11% and a HR for OS in the IMDC intermediate- and poor-risk group of 0.68 (0.58–0.81). The 60-months OS probability was 43% for ipilimumab plus nivolumab vs. 31% for sunitinib, respectively [75]. In this update the IMDC good-risk group did not continue to perform better with sunitinib although this effect occurs due to a late overlap of the KM-curves (HR for OS: 0.94 [95% CI: 0.65–1.37]) [76]. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab was associated with 15% grade 3-5 toxicity including 1.5% treatment-related deaths. It should therefore be administered in centres with experience of immune combination therapy and appropriate supportive care within the context of a multidisciplinary team. PD-L1 biomarker is currently not used to select patients for therapy. The frequency of steroid use has generated controversy and further analysis, as well as real world data, are required. For these reasons the Panel of EAU Guidelines edition 2022 continues to recommend ipilimumab and nivolumab in the intermediate- and poor-risk population. Overall survival and PFS assessed by central independent review in the ITT population were the co-primary endpoints. Response rates and assessment in the PD-L1-positive patient population were secondary endpoints. With a median follow-up of 12.8 months, at first interim analysis both primary endpoints were reached, the median PFS in the pembrolizumab plus axitinib arm was 15.1 months vs. 11.1 in the sunitinib arm (HR: 0.69, 95% CI: 0.57–0.84, p < 0.001). Median OS has not been reached initially in either arm, but the risk of death was 47% lower in the axitinib plus pembrolizumab arm when compared to the sunitinib arm (OS HR: 0.53, 95% CI: 0.38–0.74, p < 0.0001). Response rates were also higher in the experimental arm (59.3% vs. 35.7%). Efficacy occurred irrespective of IMDC group and PD-L1 status. Treatment-related AEs (> grade 3) occurred in 63% of patients receiving axitinib and pembrolizumab vs. 58% of patients receiving sunitinib. Treatment-related deaths occurred in approximately 1% in both arms.

A recent update of KEYNOTE-426 with a minimum follow-up of 35.6 months (median 42.8 months) demonstrated an ongoing OS benefit for axitinib plus pembrolizumab in the ITT population (HR: 0.73, 95% CI: 0.60–0.88, p < 0.001). Median OS for axitinib plus pembrolizumab was 45.7 months (95% CI: 43.6 – NR) vs. 40.1 month (95% CI: 34.3 – 44.2) for sunitinib with a PFS benefit (HR: 0.68, 95% CI: 0.58–0.80, p < 0.0001) which was across all IMDC subgroups for PFS, while OS was similar between axitinib plus pembrolizumab vs. sunitinib in the favourable subgroup with an OS benefit in the IMDC intermediate- and poor-risk groups. The complete response rate by independent review was 10% in the pembrolizumab plus axitinib arm and 4% in the sunitinib arm [77]. The phase III CheckMate 9ER trial randomised 651 patients to nivolumab plus cabozantinib (n = 323) or vs. sunitinib (n = 328) in treatment-naïve cc-mRCC patients. The primary endpoint of PFS assessed by central independent review in the ITT population was significantly prolonged for nivolumab plus cabozantinib (16.6 months) vs. sunitinib (8.3 months, HR: 0.51, 95% CI: 0.41–0.64, p < 0.0001). The nivolumab/cabozantinib combination also demonstrated a significant OS benefit in the secondary endpoint compared with sunitinib (HR: 0.60, CI: 0.40–0.89, p = 0.0010) after a median follow-up of 18.1 months. The independently assessed ORR was 55.7% vs. 27.1% with a complete response rate of 8% for nivolumab plus cabozantinib vs. 4.6% with sunitinib. The efficacy was observed independent of IMDC group and PD-L1 status. Treatment-related AEs (> grade 3) occurred in 61% of patients receiving cabozantinib and nivolumab vs. 51% of patients receiving sunitinib. Treatment-related deaths occurred in one patient in the nivolumab/cabozantinib arm and in two patients in the sunitinib arm. Recently, the randomised phase III trial CLEAR (Lenvatinib/Everolimus or Lenvatinib/Pembrolizumab Versus Sunitinib Alone as Treatment of Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma) was published [78]. CLEAR randomised a total of 1,069 patients (in a 1:1:1 ratio) to lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab (n = 355) vs. lenvatinib plus everolimus (n = 357) vs. sunitinib (n = 357). The trial reached its primary endpoint of independently assessed PFS at a median of 23.9 vs. 9.2 months, for lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab vs. sunitinib, respectively (HR: 0.39, 95% CI: 0.32–0.49, p < 0.001). Overall survival significantly improved with lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab vs. sunitinib (HR: 0.66, 95% CI: 0.49–0.88, p = 0.005). Objective response for lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab was 71% with 16% of the patients having a complete remission. Efficacy was observed across all IMDC risk groups, independently of PD-L1 status. Treatment-related AEs of grade 3 and higher with lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab were 72%. Treatment-related death occurred in four patients in the lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab arm and in one patient in the sunitinib arm. The JAVELIN trial investigated 886 patients in a phase III RCT of avelumab plus axitinib vs. sunitinib [79]. The trial met one of its co-primary endpoints (PFS in the PD-L1-positive population at first interim analysis [median follow up 11.5 months]). Hazard ratios for PFS and OS in the ITT population were 0.69 (95% CI: 0.56–0.84) and 0.78 (95% CI: 0.55–1.08), respectively. The same applies to the atezolizumab/bevacizumab combination which also achieved a PFS advantage over sunitinib in the PD-L1-positive population at interim analysis and ITT (HR: 0.74, 95% CI: 0.57–0.96), but has not yet shown a significant OS advantage (HR: 0.81, 95% CI: 0.63–1.03) [80]. Final OS results are awaited and the combination cannot currently be recommended.

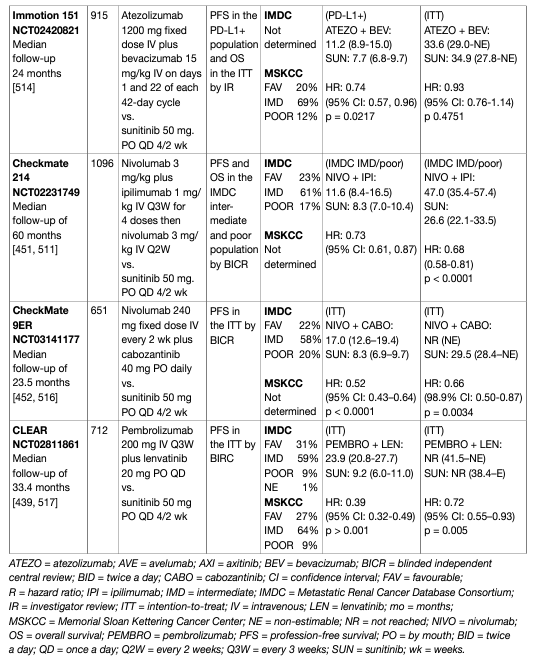

Table 3: First line immune checkpoint inhibitor combination trials for clear-cell RCC

Cross trial comparison is not recommended and should occur with caution

Patients who stop nivolumab plus ipilimumab because of toxicity require expert guidance and support from a multi-disciplinary team before re-challenge can occur. Patients who do not receive the full four doses of ipilimumab due to toxicity should continue on single-agent nivolumab, where safe and feasible. Treatment past progression with nivolumab plus ipilimumab can be justified but requires close scrutiny and the support of an expert multi-disciplinary team [80,81]. Patients who stop TKI and IO due to immune-related toxicity can receive single-agent TKI once the adverse event has resolved. Adverse event management, including transaminitis and diarrhoea, require particular attention as both agents may be causative. Expert advice should be sought on re-challenge of ICIs after significant toxicity. Treatment past progression on axitinib plus pembrolizumab or nivolumab plus cabozantinib requires careful consideration as it is biologically distinct from treatment past progression on ipilimumab and nivolumab. Generally, the Panel of EAU Guidelines edition 2022 is of the opinion that nivolumab plus ipilimumab, pembrolizumab plus axitinib and nivolumab plus cabozantinib should be administered in centres with experience of immune combination therapy and appropriate supportive care within the context of a multi-disciplinary team.

Therapeutic strategies:

- Treatment-naïve patients with clear-cell metastatic RCC

The combination of pembrolizumab plus axitinib as well as nivolumab plus cabozantinib and lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab is the standard of care in all IMDC-risk patients and ipilimumab plus nivolumab in IMDC intermediate- and poor-risk patients (Figure 1). Therefore, the role of VEGFR-TKIs alone in front-line mRCC has been superseded. Sunitinib, pazopanib, and cabozantinib (IMDC intermediate- and poor-risk disease), remain alternative treatment options for patients who cannot receive or tolerate immune checkpoint inhibition in this setting (Figure 1).

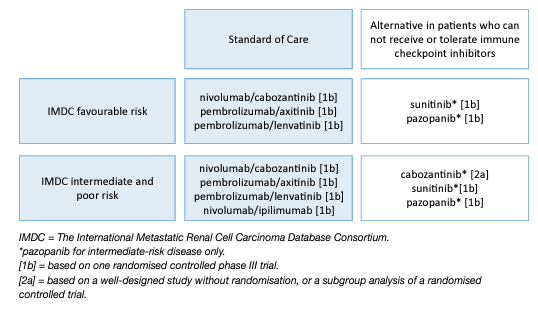

- Sequencing systemic therapy in clear-cell metastatic RCC

The sequencing of targeted therapies is established in mRCC and maximises outcomes [61,70]. Pembrolizumab plus axitinib, nivolumab plus cabozantinib, lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab and nivolumab plus ipilimumab are the new standard of care in front-line therapy. The impact of front-line immune checkpoint inhibition on subsequent therapies is unclear. Randomised data on patients with disease refractory to either nivolumab plus ipilimumab or TKI plus IO in a first-line setting are lacking, and available cohorts are limited [82]. Prospective data on tivozanib, cabozantinib and axitinib are available for patients progressing on immunotherapy, but these studies do not focus solely on the front-line setting, involve subset analyses, and are too small for definitive conclusions [70,83]. Retrospective data on VEGFR-TKI therapy after progression on front-line immune combinations exist but have significant limitations. When considering this data in totality, there is some activity but it is still too early to recommend one VEGFR-TKI over another after immunotherapy/immunotherapy or immunotherapy/VEGFR combination (Figure 2). After the axitinib plus pembrolizumab combination, changing the VEGFR-TKI at progression to cabozantinib or any other TKI not previously used is recommended. The Panel of EAU Guidelines edition 2022 do not support the use of mTOR inhibitors unless VEGF-targeted therapy is contraindicated as they have been outperformed by other VEGF-targeted therapies in mRCC [84]. Drug choice in the third-line setting, after ICI combinations and subsequent VEGF-targeted therapy, is unknown. The Panel of EAU Guidelines edition 2022 recommends a subsequent agent which is approved in VEGF-refractory disease, with the exception of re-challenge with immune checkpoint blockade. Cabozantinib is the only agent in VEGF-refractory disease with RCT data showing a survival advantage and should be used preferentially [26]. Axitinib has positive PFS data in VEGFrefractory disease. Both sorafenib and everolimus have been outperformed by other agents in VEGF-refractory disease and are therefore less attractive [84]. The lenvatinib plus everolimus combination appears superior to everolimus alone and has been granted EMA regulatory approval based on randomised phase II data. This is an alternative despite the availability of phase II data only [61]. As shown in a study which also included patients on ICIs tivozinib provides PFS superiority over sorafenib in VEGF-refractory disease [85].

Figure 1: Updated EAU Guidelines recommendations for the first-line treatment of cc-mRCC

Figure 2: EAU Guidelines recommendations for later-line therapy

Table 4: Subgroup analysis of first-line immune checkpoint inhibitor combinations in RCC patients with sarcomatoid histology Cross trial comparison is not recommended and should occur with caution

- Treatment of patients with non-clear-cell metastatic RCC

No phase III trials of patients with non-cc-mRCC have been reported. Expanded access programmes and subset analyses from RCC studies suggest the outcome of these patients with targeted therapy is poorer than for ccRCC. Targeted treatment in non-cc-mRCC has focused on temsirolimus, everolimus, sorafenib, sunitinib and pembrolizumab [86–89].

- Papillary metastatic RCC

The most common non-cc subtypes are type I and non-type I pRCCs. There are small single-arm trials for sunitinib and everolimus [90, 89–93]. A trial of both types of pRCC treated with everolimus (RAPTOR), showed a median PFS of 3.7 months per central review in the ITT population with a median OS of 21.0 months [93]. In a non-randomised phase II trial, type 2 pRCC associated with HLRCC, a familial cancer syndrome caused by germline mutations in the fumarate hydratase enzyme gene, the combination of bevacizumab 10 mg/kg IV every two weeks and erlotinib 150 mg orally daily has been evaluated [94]. The combination regimen reports interesting activity with an ORR of 64% (27/42, 95% CI: 49–77) in the HLRCC cohort, with a median PFS of 21.1 months (95% CI: 15.6–26.6). Grade > 3 treatment-related AEs occurred in 47% of patients, including hypertension (34%) and proteinuria (13%). For pRCC new evidence is available from the SWOG PAPMET randomised phase II trial which compared sunitinib to cabozantinib, crizotinib and savolitinib in 152 patients with papillary mRCC [95]. Progressionfree survival was longer in patients in the cabozantinib group (median 9.0 months, 95% CI: 6–12) than in the sunitinib group (5.6 months, CI: 3–7; HR for progression or death 0.60 [0.37–0.97, one-sided p = 0.019]). Response rate for cabozantinib was 23% vs. 4% for sunitinib (two-sided p = 0.010). Savolitinib and crizotinib did not improve PFS compared with sunitinib. Grade 3 or 4 AEs occurred in 69% (31/45) of patients receiving sunitinib, 74% (32/43) of patients receiving cabozantinib, 37% (10/27) receiving crizotinib, and 39% (11/28) receiving savolitinib; one grade 5 thromboembolic event was recorded in the cabozantinib group. These results support adding cabozantinib as an option for patients with papillary mRCC based on superior PFS results compared to sunitinib. In addition, savolitinib was investigated in the SAVOIR trial [96] as first-line treatment for MET-driven tumours defined as chromosome 7 gain, MET amplification, MET kinase domain variations or hepatocyte growth factor amplification by DNA alteration analysis (~30% of screened patients were MET positive). In a limited patient group, savolitinib (n = 27) was compared with sunitinib (n = 33). The trial was stopped early, largely due to poor accrual. The efficacy data appeared to favour savolitinib (median PFS 7.0 months, 95% CI: 2.8 months-NR vs. 5.6 months, 95% CI: 4.1–6.9 months, PFS HR: 0.71, 95% CI: 0.37–1.36, OS HR: 0.51,94% CI: 0.21–1.17, RR: 27% vs. 7%, for savolitinib and sunitinib, respectively). The median OS for savolitinib was NR. Savolitinib was better tolerated compared with sunitinib with 42% grade > 3 AEs compared to 81% with sunitinib. Efficacy for pembrolizumab in the pRCC subset (118/165) was; RR: 29%, PFS: 5.5 months (95% CI: 3.9–6.1 months) and OS: 31.5 months (95% CI: 25.5 months-NR), but these results are based on a single-arm phase II study [72]. Pembrolizumab can be conceded in this setting due to the high unmet need. Patients with non-cc-mRCC should be referred to a clinical trial, where appropriate.

Treatment of patients with rare tumours:

- Renal medullary carcinoma

Renal medullary carcinoma is one of the most aggressive RCCs [97,98] and most patients (~67%) will present with metastatic disease [97,99]. Even patients who present with seemingly localised disease may develop macrometastases shortly thereafter, often within a few weeks. Despite treatment, median OS is thirteen months in the most recent series [100]. Due to the infiltrative nature and medullary epicentre of RMC, RN is favoured over PN even in very early-stage disease. Retrospective data indicate that nephrectomy in localised disease results in superior OS (16.4 vs. 7 months) compared with systemic chemotherapy alone, but longer survival was noted in patients who achieved an objective response to first-line chemotherapy [100,101]. There is currently no established role for distant metastasectomy or nephrectomy in the presence of metastases. Palliative radiation therapy is an option and may achieve regression in the targeted areas but it will not prevent progression outside the radiation field [102,103]. Renal medullary carcinoma is refractory to monotherapies with targeted anti-angiogenic regimens including TKIs and mTOR inhibitors [100, 104]. The mainstay systemic treatments for RMC are cytotoxic combination regimens which produce partial or complete responses in ~29% of patients [104]. There are no prospective comparisons between different chemotherapy regimens but most published series used various combinations of platinum agents, taxanes, gemcitabine, and/or anthracyclines [100,105]. High-dose-intensity combination of MVAC has also shown efficacy against RMC [106] although a retrospective comparison did not show superiority of MVAC over cisplatin, paclitaxel, and gemcitabine [105]. Single-agent anti-PD-1 immune checkpoint therapy has produced responses in a few case reports, although, as yet, insufficient data are available to determine the response rate to this approach [102, 103]. Whenever possible, patients should be enrolled in clinical trials of novel therapeutic approaches, particularly after failing first-line cytotoxic chemotherapy.

Treatment of hereditary RCC:

- von-Hippel-Lindau-disease-associated RCC

Patients with VHL disease often develop RCC and tumours in other organs including CNS, retinal haemangioblastomas, and pancreatic tumours, and commonly undergo several surgical resections in their lifetime. In VHL disease, belzutifan, a hypoxia-inducible factor 2α (HIF-2α) inhibitor, has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of ccRCC and other neoplasms associated with VHL for the treatment of tumours that do not require immediate surgery. Approval was based on the results from a phase II, open-label, single-arm trial in patients with tumours not larger than 3 cm [107]. Belzutifan induced partial responses with an RCC ORR of 49%, and a disease control rate of 98.4% after 21.8 months treatment. All patients with pancreatic lesions had an ORR of 77%, and those with CNS haemangioblastoma had a 30% response rate. In total, 33% of patients reported > grade 3 AEs, and seven patients (11.5%) discontinued the treatment. In the treatment with pazopanib for VHL only 52% continued with the treatment after 24 weeks [108]. With favourable efficacy results and with relatively low-grade side effects, belzutifan seems to be a valuable contribution to the treatment of patients with the VHL disease, and it is currently under review by the EMA.

- Locally recurrent RCC after treatment of localised disease

Most studies reporting on local recurrent disease after removal of the kidney have not considered the true definition of local recurrence after RN, PN and thermal ablation, which are: local recurrence in the tumourbearing kidney, tumour growth exclusively confined to the true renal fossa, recurrences within the renal vein, the ipsilateral adrenal gland or the regional LNs. In the existing literature the topic is weakly investigated and often regarded as local recurrent disease.

- Locally recurrent RCC after nephron-sparing approaches

Locally recurrent disease can affect the tumour-bearing kidney after PN or focal ablative therapy such as RFA and cryotherapy. Local relapse may be due to the incomplete resection of the primary tumour, in a minority of the cases to the local spread of the tumour by microvascular embolisation, or true multifocality [109, 110]. The prognosis of recurrent disease not due to multifocality is poor, despite salvage nephrectomy [110]. Recurrent tumour growth in the regional LNs or ipsilateral adrenal gland may reflect metachronous metastatic spread. After treatment solely for localised disease, systemic progression is common [111, 112]. Following thermal ablation or cryotherapy generally intra-renal, but also peri-renal, recurrences have been reported in up to 14% of cases [113]. Whereas repeat ablation is still recommended as the preferred therapeutic option after treatment failure, the most effective salvage procedure as an alternative to complete nephrectomy has not yet been defined.

- Locally recurrent RCC after radical nephrectomy

Isolated local fossa recurrence is rare and occurs in about 1-3% after radical nephrectomy. More commonly in pT3-4 than pT1-2 and grade 3-4. Most patients with local recurrence of RCC are diagnosed by either CT/MRI scans as part of the post-operative follow-up [114]. The median time to recurrence after RN was 19-36 months in isolated local recurrence or 14.5 months in group including metastatic cases as well [114–116]. Isolated local recurrence is associated with worse survival [109, 117]. Based on retrospective and noncomparative data only, several approaches such as surgical excision, radiotherapy, systemic treatment and observation have been suggested for the treatment of isolated local recurrence [118–120]. Among these alternatives, surgical resection with negative margins remains the only therapeutic option shown to be associated with improved survival [117]. Open surgery has been successfully reported in studies [121, 122]. One of the largest series including 2,945 patients treated with RN reported on 54 patients with recurrent disease localised in the renal fossa, the ipsilateral adrenal gland or the regional LNs as sole metastatic sites [118]. Another recent series identified 33 patients with isolated local recurrences and 30 local recurrences with synchronous metastases within a cohort of 2,502 surgically treated patients, confirming the efficacy of locally directed treatment vs. conservative approaches (observation, systemic therapy) [123]. A five-year OS with isolated local recurrence was 60% (95% CI: 0.44–0.73) and ten-year OS was 32% (95% CI: 0.15–0.51). Overall survival differed significantly by the time period between primary surgery and occurrence of recurrence (< two years vs. > two years: ten-year OS rate 31% (95% CI: 10.2–55.0) vs. 45% (95% CI: 21.5–65.8; HR: 0.26; p = 0.0034) [114]. Metastatic progression was observed in 60 patients (58.8%) after surgery [115]. Patient survival can be linked to the type of treatment received, as shown by Marchioni, et al. In a cohort of 96 patients, 45.8% were metastatic at the time of recurrence; three-year CSS rates after local recurrence were 92.3% (± 7.4%) for those who were treated with surgery and systemic therapy, 63.2% (± 13.2%) for those who only underwent surgery, 22.7% (± 0.9%) for those who only received systemic therapy and 20.5% (± 10.4%) for those who received no treatment (p < 0.001). However, minimally invasive approaches, including standard and hand-assisted laparoscopic- and robotic approaches for the resection of isolated RCC recurrences have been occasionally reported. Recently, Martini et al., published the largest surgical cohort of robotic surgery in this setting (n = 35) providing a standardisation of the nomenclature, describing the surgical technique for each scenario and reporting on complications, renal function, and oncologic outcomes [124]. Ablative therapies including cryoablation, radiofrequency and microwave ablation, may also have a role in managing recurrent RCC patients, but further validation will be needed [125, 126]. In summary, the limited available evidence suggests that in selected patients’ surgical removal of locally recurrent disease with negative margins can induce durable tumour control, although with expected high risk of complications. Johnson et al. published on 51 planned repeat PNs in 47 patients with locally recurrent disease, reporting a total of 40 peri-operative complications, with temporary urinary extravasation being the most prevalent [127]. Since local recurrences develop early, with a median time interval of 10–20 months after treatment of the primary tumour [128], a guideline-adapted follow-up scheme for early detection is recommended (see Chapter 8 – Follow-up) even though benefit in terms of cancer control has not yet been demonstrated [129]. Adverse prognostic parameters are a short time interval since treatment of the primary tumour (< 3–12 months) [130], sarcomatoid differentiation of the recurrent lesion and incomplete surgical resection [118]. In case complete surgical removal is unlikely to be performed or when significant comorbidities are present (especially when combined with poor prognostic tumour features), palliative therapeutic approaches including radiation therapy aimed at symptom control and prevention of local complications should be considered. Following metastasectomy of local recurrence after nephrectomy, adjuvant therapy can be considered. Neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapy). Local recurrence combined with other metastases is treated as a metastatic RCC.

FOLLOW-UP IN RCC:

- Introduction

Surveillance after treatment for RCC allows the urologist to monitor or identify:

• post-operative complications;

• renal function;

• local recurrence;

• recurrence in the contralateral kidney;

• distant metastases;

• cardiovascular events.

There is no consensus on follow-up strategies after RCC treatment, with limited evidence suggesting that more frequent post-operative imaging intervals do not provide any improvement for early detection of recurrence that would lead to improved survival [129]. As such, intensive radiological surveillance may not be necessary for all patients. Follow-up is also important to assess functional outcomes and to limit long-term sequelae such as renal function impairment, end-stage renal disease and cardiovascular events [131]. Currently, the key question is whether any recurrence detection during follow-up and subsequent treatment will lead to any meaningful change in survival outcome for these patients. In contrast to high-grade and/or locally advanced disease, the outcome after surgery for T1a low-grade tumours is almost always excellent. It is therefore reasonable to stratify follow-up, taking into account the risk of each different RCC to develop a local or distant recurrence. Although there is no randomised evidence, large studies have examined prognostic factors with long follow-up [132, 133, 134]. One study has shown a survival benefit in patients who were followed within a structured surveillance protocol vs. patients who were not [135]; patients undergoing follow-up seem to have a longer OS when compared to patients not undergoing routine follow-up [135]. Furthermore, an individualised and risk-based approach to RCC follow-up has recently been proposed. The authors used competing risk models, incorporating patient age, pathologic stage, relapse location and comorbidities, to calculate when the risk of non-RCC death exceeds the risk of RCC recurrence [136]. For patients with low-stage disease but with a Charlson comorbidity index > 2, the risk of non-RCC death exceeded that of abdominal recurrence risk already one month after surgery, regardless of patient age.

The RECUR consortium, initiated by this Panel of EAU Guidelines edition 2022, collects similar data with the aim to provide comparators for guideline recommendations. Recently published RECUR data support a risk-based approach; more specifically a competing-risk analysis showed that for low-risk patients, the risk of non-RCC related death exceeded the risk of RCC recurrence shortly after the initial surgery. For intermediate-risk patients, the corresponding time point was reached around four to five years after surgery. In high-risk patients, the risk of RCC recurrence continuously exceeded the risk of non-RCC related death [137]. In the near future, genetic profiling may refine the existing prognostic scores and external validation in datasets from adjuvant trials have been promising in improving stratification of patient’s risk of recurrence [137, 138]. Recurrence after PN is rare, but early diagnosis is relevant, as the most effective treatment is surgery [121, 139]. Recurrence in the contralateral kidney is rare (1–2%) and can occur late (median 5–6 years) [140]. Follow-up can identify local recurrences or metastases at an early stage. In metastatic disease, extended tumour growth can limit the opportunity for surgical resection, which is considered the standard therapy in cases of resectable and preferably solitary lesions. In addition, early diagnosis of tumour recurrence may enhance the efficacy of systemic treatment if the tumour burden is low.

- Which imaging investigations for which patients, and when?

• The sensitivity of chest radiography and US for detection of small RCC metastases is poor. The sensitivity of chest radiography is significantly lower than CT-scans, as proven in comparative studies including histological evaluation [141–143]. Therefore, follow-up for recurrence detection with chest radiography and US are less sensitive [144].

• Positron-emission tomography and PET-CT as well as bone scintigraphy should not be used routinely in RCC follow-up, due to their limited specificity and sensitivity [145, 146].

• Surveillance should also include evaluation of renal function and cardiovascular risk factors [131].

• Outside the scope of regular follow-up imaging of the chest and abdomen, targeted imaging should be considered in patients with organ-specific symptoms, e.g., CT or MRI imaging of the brain in patients experiencing neurological symptoms [147].

Controversy exists on the optimal duration of follow-up. Some authors argue that follow-up with imaging is not cost-effective after five years; however, late metastases are more likely to be solitary and justify more aggressive therapy with curative intent. In addition, patients with tumours that develop in the contralateral kidney can be treated with NSS if the tumours are detected early. Several authors have designed scoring systems and nomograms to quantify the likelihood of patients to develop tumour recurrences, metastases, and subsequent death [148, 149, 150, 151]. These models, of which the most utilised are summarised in Chapter 6 – Prognosis, have been compared and validated [152]. Using prognostic variables, several stage-based follow-up regimens have been proposed, although, none propose follow-up strategies after ablative therapies [153, 154]. A post-operative nomogram is available to estimate the likelihood of freedom from recurrence at five years [155]. Recently, a pre-operative prognostic model based on age, symptoms and TNM staging has been published and validated [156]. A follow-up algorithm for monitoring patients after treatment for RCC is needed, recognising not only the patient’s risk of recurrence profile, but also the efficacy of the treatment given (Table 5). These prognostic systems can be used to adapt the follow-up schedule according to predicted risk of recurrence. Ancillary to the above, life-expectancy calculations based on comorbidity and age at diagnosis may be useful in counselling patients on duration of follow-up [157].

Table 5: Proposed follow-up schedule following treatment for localised RCC, taking into account patient risk of recurrence profile and treatment efficacy (based on expert opinion)

REFERENCES:

- Flanigan, R.C., et al. Cytoreductive nephrectomy in patients with metastatic renal cancer: a combined analysis. J Urol, 2004. 171: 1071. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14767273/

- Tsui, K.H., et al. Prognostic indicators for renal cell carcinoma: a multivariate analysis of 643 patients using the revised 1997 TNM staging criteria. J Urol, 2000. 163: 1090. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10737472/

- Clinical Trial to Assess the Importance of Nephrectomy (CARMENA). 2009. 2019 p. NCT00930033. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00930033

- Bhindi, B., et al. Systematic Review of the Role of Cytoreductive Nephrectomy in the Targeted Therapy Era and Beyond: An Individualized Approach to Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma. Eur Urol, 2019. 75: 111. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30467042/

- Mejean, A., et al. Sunitinib Alone or after Nephrectomy in Metastatic Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med, 2018. 379: 417. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29860937/

- Bex, A., et al. Comparison of Immediate vs Deferred Cytoreductive Nephrectomy in Patients With Synchronous Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Receiving Sunitinib: The SURTIME Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol, 2019. 5: 164. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30543350/

- Powles, T., et al. The outcome of patients treated with sunitinib prior to planned nephrectomy in metastatic clear cell renal cancer. Eur Urol, 2011. 60: 448. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21612860/

- Heng, D.Y., et al. Cytoreductive nephrectomy in patients with synchronous metastases from renal cell carcinoma: results from the International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium. Eur Urol, 2014. 66: 704. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24931622/

- de Bruijn, R., et al. Deferred Cytoreductive Nephrectomy Following Presurgical Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor-targeted Therapy in Patients with Primary Metastatic Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Pooled Analysis of Prospective Trial Data. Eur Urol Oncol, 2020. 3: 168. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31956080/

- Ljungberg, B., et al. Survival advantage of upfront cytoreductive nephrectomy in patients with primary metastatic renal cell carcinoma compared with systemic and palliative treatments in a realworld setting. Scand J Urol, 2020. 54: 487. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32897123/

- Maxwell, N.J., et al. Renal artery embolisation in the palliative treatment of renal carcinoma. Br J Radiol, 2007. 80: 96. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17495058/

- Lamb, G.W., et al. Management of renal masses in patients medically unsuitable for nephrectomy-natural history, complications, and outcome. Urology, 2004. 64: 909. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15533476/

- Hallscheidt, P., et al. [Preoperative and palliative embolization of renal cell carcinomas: follow-up of 49 patients]. Rofo, 2006. 178: 391. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16612730/

- Dabestani, S., et al. Local treatments for metastases of renal cell carcinoma: a systematic review. Lancet Oncol, 2014. 15: e549. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25439697/

- Dabestani, S., et al. EAU Renal Cell Carcinoma Guideline Panel. Systematic review methodology for the EAU RCC Guideline 2013. [No abstract available].

- Brinkmann, O.A., et al. The Role of Residual Tumor Resection in Patients with Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma and Partial Remission following Immunochemotherapy. Eur Urol Suppl, 2007. 6: 641. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1569905607000978

- Alt, A.L., et al. Survival after complete surgical resection of multiple metastases from renal cell carcinoma. Cancer, 2011. 117: 2873. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21692048/

- Kwak, C., et al. Metastasectomy without systemic therapy in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: comparison with conservative treatment. Urol Int, 2007. 79: 145. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17851285/

- Petralia, G., et al. 450 Complete metastasectomy is an independent predictor of cancer-specific survival in patients with clinically metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol Suppl, 2010. 9: 162. https://www.eusupplements.europeanurology.com/article/S1569-9056(10)60446-0/abstract

- Russo, P., et al. Cytoreductive nephrectomy and nephrectomy/complete metastasectomy for metastatic renal cancer. Sci World J, 2007. 7: 768. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17619759/

- Staehler, M.D., et al. Metastasectomy significantly prolongs survival in patients with metastatic renal cell cancer. J Urol, 2009. 181: 498. https://www.auajournals.org/article/S0022-5347(09)61409-9/pdf

- Eggener, S.E., et al. Risk score and metastasectomy independently impact prognosis of patients with recurrent renal cell carcinoma. J Urol, 2008. 180: 873. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18635225/

- Lee, S.E., et al. Metastatectomy prior to immunochemotherapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Urol Int, 2006. 76: 256. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16601390/

- Fuchs, B., et al. Solitary bony metastasis from renal cell carcinoma: significance of surgical treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2005: 187. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15685074/

- Hunter, G.K., et al. The efficacy of external beam radiotherapy and stereotactic body radiotherapy for painful spinal metastases from renal cell carcinoma. Pract Radiat Oncol, 2012. 2: e95. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24674192/

- Zelefsky, M.J., et al. Tumor control outcomes after hypofractionated and single-dose stereotactic image-guided intensity-modulated radiotherapy for extracranial metastases from renal cell carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2012. 82: 1744. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21596489/

- Fokas, E., et al. Radiotherapy for brain metastases from renal cell cancer: should whole-brain radiotherapy be added to stereotactic radiosurgery?: analysis of 88 patients. Strahlenther Onkol, 2010. 186: 210. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20165820/

- Ikushima, H., et al. Fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy of brain metastases from renal cell carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2000. 48: 1389. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11121638/

- Staehler, M.D., et al. Liver resection for metastatic disease prolongs survival in renal cell carcinoma: 12-year results from a retrospective comparative analysis. World J Urol, 2010. 28: 543. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20440505/

- Amiraliev, A. Treatment strategy in patients with pulmonary metastases of renal cell cancer. Int Cardiovasc Thor Surg, 2012. S20. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/284295837

- Zerbi, A., et al. Pancreatic metastasis from renal cell carcinoma: which patients benefit from surgical resection? Ann Surg Oncol, 2008. 15: 1161. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18196343/

- Kickuth, R., et al. Interventional management of hypervascular osseous metastasis: role of embolotherapy before orthopedic tumor resection and bone stabilization. AJR Am J Roentgenol, 2008. 191: W240. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19020210/

- Forauer, A.R., et al. Selective palliative transcatheter embolization of bony metastases from renal cell carcinoma. Acta Oncol, 2007. 46: 1012. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17851849/

- Appleman, L.J., et al. Randomized, double-blind phase III study of pazopanib versus placebo in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma who have no evidence of disease following metastasectomy: A trial of the ECOG-ACRIN cancer research group (E2810). J Clin Oncol, 2019. 37: 4502. https://ascopubs.org/doi/abs/10.1200/JCO.2019.37.15_suppl.4502

- Procopio, G., et al. Sorafenib Versus Observation Following Radical Metastasectomy for Clear-cell Renal Cell Carcinoma: Results from the Phase 2 Randomized Open-label RESORT Study. Eur Urol Oncol, 2019. 2: 699. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31542243/

- Hebbadj, S., et al. Safety Considerations and Local Tumor Control Following Percutaneous ImageGuided Cryoablation of T1b Renal Tumors. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol, 2018. 41: 449. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29075877/

- Grange, R., et al. Computed tomography-guided percutaneous cryoablation of T1b renal tumors: safety, functional and oncological outcomes. Int J Hyperthermia, 2019. 36: 1065. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31648584/

- Amato, R.J. Chemotherapy for renal cell carcinoma. Semin Oncol, 2000. 27: 177. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10768596/

- Pecoraro, A., et al. Cryoablation Predisposes to Higher Cancer Specific Mortality Relative to Partial Nephrectomy in Patients with Nonmetastatic pT1b Kidney Cancer. J Urol, 2019. 202: 1120. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31347950/

- Andrews, J.R., et al. Oncologic Outcomes Following Partial Nephrectomy and Percutaneous Ablation for cT1 Renal Masses. Eur Urol, 2019. 76: 244. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31060824/

- Sundelin, M.O., et al. Repeated Cryoablation as Treatment Modality after Failure of Primary Renal Cryoablation: A European Registry for Renal Cryoablation Multinational Analysis. J Endourol, 2019. 33: 909. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31507206/

- Heng, D.Y., et al. External validation and comparison with other models of the International Metastatic Renal-Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium prognostic model: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol, 2013. 14: 141. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23312463/

- Escudier, B., et al. Sorafenib in advanced clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med, 2007. 356: 125. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17215530/

- Bellmunt, J., et al. The medical treatment of metastatic renal cell cancer in the elderly: position paper of a SIOG Taskforce. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol, 2009. 69: 64. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18774306/

- Motzer, R.J., et al. Overall survival and updated results for sunitinib compared with interferon alfa in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol, 2009. 27: 3584. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19487381/

- Motzer, R.J., et al. Randomized phase II trial of sunitinib on an intermittent versus continuous dosing schedule as first-line therapy for advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol, 2012. 30: 1371. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22430274/

- Bracarda, S., et al. Sunitinib administered on 2/1 schedule in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: the RAINBOW analysis. Ann Oncol, 2016. 27: 366. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26685011/

- Jonasch, E., et al. A randomized phase 2 study of MK-2206 versus everolimus in refractory renal cell carcinoma. Ann Oncol, 2017. 28: 804. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28049139/

- Sternberg, C.N., et al. Pazopanib in locally advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma: results of a randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol, 2010. 28: 1061. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20100962/

- Motzer, R.J., et al. Pazopanib versus sunitinib in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med, 2013. 369: 722. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23964934/

- Escudier, B., et al. Randomized, controlled, double-blind, cross-over trial assessing treatment preference for pazopanib versus sunitinib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: PISCES Study. J Clin Oncol, 2014. 32: 1412. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24687826/

- Rini, B.I., et al. Comparative effectiveness of axitinib versus sorafenib in advanced renal cell carcinoma (AXIS): a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet, 2011. 378: 1931. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22056247/

- Dror Michaelson M., et al. Phase III AXIS trial of axitinib versus sorafenib in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: Updated results among cytokine-treated patients. J Clin Oncol 2012. J Clin Oncol 30, 2012 (suppl; abstr 4546). https://ascopubs.org/doi/abs/10.1200/jco.2012.30.15_suppl.4546

- Motzer, R.J., et al. Axitinib versus sorafenib as second-line treatment for advanced renal cell carcinoma: overall survival analysis and updated results from a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol, 2013. 14: 552. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23598172/

- Hutson, T.E., et al. Axitinib versus sorafenib as first-line therapy in patients with metastatic renal-cell carcinoma: a randomised open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol, 2013. 14: 1287. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24206640/

- Choueiri, T.K., et al. A phase I study of cabozantinib (XL184) in patients with renal cell cancer. Ann Oncol, 2014. 25: 1603. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24827131/

- Choueiri, T.K., et al. Cabozantinib versus Everolimus in Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med, 2015. 373: 1814. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26406150/

- Choueiri, T.K., et al. Cabozantinib versus everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma (METEOR): final results from a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol, 2016. 17: 917. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27279544/

- Choueiri, T.K., et al. Cabozantinib Versus Sunitinib As Initial Targeted Therapy for Patients With Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma of Poor or Intermediate Risk: The Alliance A031203 CABOSUN Trial. J Clin Oncol, 2017. 35: 591. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28199818/

- Choueiri, T.K., et al. Cabozantinib versus sunitinib as initial therapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma of intermediate or poor risk (Alliance A031203 CABOSUN randomised trial): Progressionfree survival by independent review and overall survival update. Eur J Cancer, 2018. 94: 115. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29550566/

- Motzer, R.J., et al. Lenvatinib, everolimus, and the combination in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a randomised, phase 2, open-label, multicentre trial. Lancet Oncol, 2015. 16: 1473. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26482279/

- Motzer, R.J., et al. Tivozanib versus sorafenib as initial targeted therapy for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: results from a phase III trial. J Clin Oncol, 2013. 31: 3791. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24019545/

- Molina, A.M., et al. Efficacy of tivozanib treatment after sorafenib in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma: crossover of a phase 3 study. Eur J Cancer, 2018. 94: 87. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29547835/

- Escudier B., et al. Phase III trial of bevacizumab plus interferon alfa-2a in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (AVOREN): final analysis of overall survival. J Clin Oncol, 2010. 28: 2144. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20368553/

- Rini, B.I., et al. Bevacizumab plus interferon alfa compared with interferon alfa monotherapy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: CALGB 90206. J Clin Oncol, 2008. 26: 5422. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18936475/

- Rini, B.I., et al. Phase III trial of bevacizumab plus interferon alfa versus interferon alfa monotherapy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: final results of CALGB 90206. J Clin Oncol, 2010. 28: 2137. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20368558/

- Larkin, J.M., et al. Kinase inhibitors in the treatment of renal cell carcinoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol, 2006. 60: 216. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16860997/

- Motzer, R.J., et al. Efficacy of everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase III trial. Lancet, 2008. 372: 449. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18653228/

- Ribas, A. Tumor immunotherapy directed at PD-1. N Engl J Med, 2012. 366: 2517. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22658126/

- Motzer, R.J., et al. Nivolumab versus Everolimus in Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med, 2015. 373: 1803. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26406148/

- Motzer, R.J., et al. Nivolumab versus everolimus in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma: Updated results with long-term follow-up of the randomized, open-label, phase 3 CheckMate 025 trial. Cancer, 2020. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32673417/

- McDermott, D.F.L., et al. Pembrolizumab monotherapy as first-line therapy in advanced clear cell renal cell carcinoma (accRCC): Results from cohort A of KEYNOTE-427. J Clin Oncol, 2018. 36. https://ascopubs.org/doi/abs/10.1200/JCO.2018.36.15_suppl.4500

- Bissada, N.K., et al. Long-term experience with management of renal cell carcinoma involving the inferior vena cava. Urology, 2003. 61: 89. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12559273/

- Ljungberg, B., et al. European Association of Urology Guidelines on Renal Cell Carcinoma: The 2019 Update. Eur Urol, 2019. 75: 799. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30803729/

- Albiges, L., et al. 711P Nivolumab + ipilimumab (N+I) vs sunitinib (S) for first-line treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma (aRCC) in CheckMate 214: 4-year follow-up and subgroup analysis of patients (pts) without nephrectomy. Ann Oncol, 2020. 31: S559. https://www.annalsofoncology.org/article/S0923-7534(20)40779-3/fulltext

- Motzer, R.J., et al. 661P Conditional survival and 5-year follow-up in CheckMate 214: First-line nivolumab + ipilimumab (N+I) versus sunitinib (S) in advanced renal cell carcinoma (aRCC). Ann Oncol, 2021. 32: S685. https://www.annalsofoncology.org/article/S0923-7534(21)02271-7/fulltext

- Rini, B.I., et al. Pembrolizumab (pembro) plus axitinib (axi) versus sunitinib as first-line therapy for advanced clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC): Results from 42-month follow-up of KEYNOTE-426. J Clin Oncol, 2021. 39: 4500. https://www.urotoday.com/conference-highlights/asco-2021/asco-2021-kidney-cancer/130182

- Motzer, R., et al. Lenvatinib plus Pembrolizumab or Everolimus for Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med, 2021. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33616314/

- Motzer, R.J., et al. Avelumab plus Axitinib versus Sunitinib for Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med, 2019. 380: 1103. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30779531/

- Tannir, N.M., et al. Thirty-month follow-up of the phase III CheckMate 214 trial of first-line nivolumab + ipilimumab (N+I) or sunitinib (S) in patients (pts) with advanced renal cell carcinoma (aRCC). J Clin Oncol, 2019. 37: 547. https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.2019.37.7_suppl.547

- Motzer R.J., et al. Nivolumab + Ipilimumab (N+I) vs Sunitinib (S) for treatment─naïve advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma (aRCC): results from CheckMate 214, including overall survival by subgroups J Immunother Cancer, 2017. Late breaking abstracts, 32nd Annual Meeting and Precomference Programs of the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer: 038.

- Auvray, M., et al. Second-line targeted therapies after nivolumab-ipilimumab failure in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Eur J Cancer, 2019. 108: 33. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30616146/

- Ornstein, M.C., et al. phase II multi-center study of individualized axitinib (Axi) titration for metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) after treatment with PD-1 / PD-L1 inhibitors. J Clin Oncol, 2018. 36. https://ascopubs.org/doi/abs/10.1200/JCO.2018.36.15_suppl.4517

- Coppin, C., et al. Targeted therapy for advanced renal cell cancer (RCC): a Cochrane systematic review of published randomised trials. BJU Int, 2011. 108: 1556. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21952069/

- Rini, B.I., et al. Tivozanib versus sorafenib in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma (TIVO-3): a phase 3, multicentre, randomised, controlled, open-label study. Lancet Oncol, 2020. 21: 95. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31810797/

- Hudes, G., et al. Temsirolimus, interferon alfa, or both for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med, 2007. 356: 2271. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17538086/

- Gore, M.E., et al. Safety and efficacy of sunitinib for metastatic renal-cell carcinoma: an expandedaccess trial. Lancet Oncol, 2009. 10: 757. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19615940/

- Sánchez P., et al. Non-clear cell advanced kidney cancer: is there a gold standard? Anticancer Drugs 2011. 22 S9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21173605/

- Koh, Y., et al. Phase II trial of everolimus for the treatment of nonclear-cell renal cell carcinoma. Ann Oncol, 2013. 24: 1026. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23180114/

- Fernández-Pello, S., et al. A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Comparing the Effectiveness and Adverse Effects of Different Systemic Treatments for Non-clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Eur Urol, 2017. 71: 426. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27939075/

- Tannir, N.M., et al. A phase 2 trial of sunitinib in patients with advanced non-clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol, 2012. 62: 1013. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22771265/

- Ravaud A., et al. First-line sunitinib in type I and II papillary renal cell carcinoma (PRCC): SUPAP, a phase II study of the French Genito-Urinary Group (GETUG) and the Group of Early Phase trials (GEP) J. Clin Oncol, 2009. Vol 27, No 15S: 5146. https://ascopubs.org/doi/abs/10.1200/jco.2009.27.15_suppl.5146

- Escudier, B., et al. Open-label phase 2 trial of first-line everolimus monotherapy in patients with papillary metastatic renal cell carcinoma: RAPTOR final analysis. Eur J Cancer, 2016. 69: 226. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27680407/

- Srinivasan, R., et al. Results from a phase II study of bevacizumab and erlotinib in subjects with advanced hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC) or sporadic papillary renal cell cancer. J Clin Oncol, 2020. 38: 5004. https://ascopubs.org/doi/abs/10.1200/JCO.2020.38.15_suppl.5004

- Pal, S.K., et al. A comparison of sunitinib with cabozantinib, crizotinib, and savolitinib for treatment of advanced papillary renal cell carcinoma: a randomised, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet, 2021. 397: 695. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33592176/

- Choueiri, T.K., et al. Efficacy of Savolitinib vs Sunitinib in Patients With MET-Driven Papillary Renal Cell Carcinoma: The SAVOIR Phase 3 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol, 2020. 6: 1247. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32469384/

- Keegan, K.A., et al. Histopathology of surgically treated renal cell carcinoma: survival differences by subtype and stage. J Urol, 2012. 188: 391. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22698625/

- Linehan, W.M., et al. Comprehensive Molecular Characterization of Papillary Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med, 2016. 374: 135. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26536169/

- Hora, M. Re: Philip S. Macklin, Mark E. Sullivan, Charles R. Tapping, et al. Tumour Seeding in the Tract of Percutaneous Renal Tumour Biopsy: A Report on Seven Cases from a UK Tertiary Referral Centre. Eur Urol 2019;75:861-7. Eur Urol, 2019. 76: e96. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31255420/

- Shah, A.Y., et al. Management and outcomes of patients with renal medullary carcinoma: a multicentre collaborative study. BJU Int, 2017. 120: 782. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27860149/