Upper Urinary Tract Urothelial Carcinoma

Comprehensive Review Article

Prof. Dr. Semir. A. Salim. Al Samarrai

EPIDEMIOLOGY, AETIOLOGY AND PATHOLOGY:

- Epidemiology

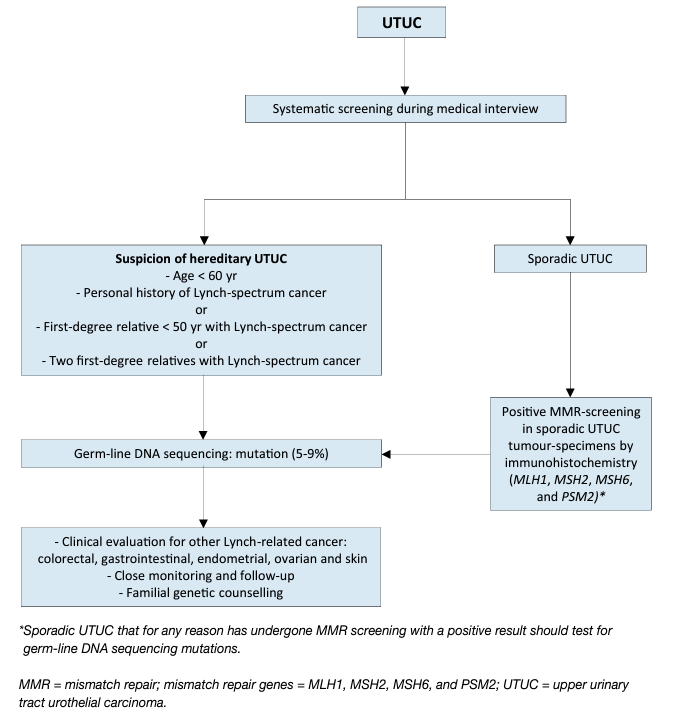

Urothelial carcinomas are the sixth most common tumours in developed countries [1]. They can be located in the lower (bladder and urethra) and/or the upper (pyelocaliceal cavities and ureter) urinary tract. Bladder tumours account for 90–95% of UCs and are the most common urinary tract malignancy [2]. Upper urinary tract UCs are uncommon and account for only 5–10% of UCs [1] with an estimated annual incidence in Western countries of almost two cases per 100,000 inhabitants. This rate has risen in the past few decades as a result of improved detection and improved bladder cancer survival [3,4]. Pyelocaliceal tumours are approximately twice as common as ureteral tumours and multifocal tumours are found in approximately 10–20% of cases [5]. The presence of concomitant carcinoma in situ of the upper tract is between 11% and 36% [3]. In 17% of cases, concurrent bladder cancer is present [6] whilst a prior history of bladder cancer is found in 41% of American men but in only 4% of Chinese men [7]. This, along with genetic and epigenetic factors, may explain why Asian patients present with more advanced and higher-grade disease compared to other ethnic groups [3]. Following treatment, recurrence in the bladder occurs in 22–47% of UTUC patients, depending on initial tumour grade [8] compared with 2–5% in the contralateral upper tract [9]. With regards to UTUC occurring following an initial diagnosis of bladder cancer, a series of 82 patients treated with bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) who had regular upper tract imaging between years 1 and 3 showed a 13% incidence of UTUC, all of which were asymptomatic [10], whilst in another series of 307 patients without routine upper tract imaging the incidence was 25% [11]. A multicentre cohort study (n = 402) with a 50-month follow-up has demonstrated a UTUC incidence of 7.5% in NMIBC receiving BCG with predictors being intravesical recurrence and non-papillary tumour at transurethral resection of the bladder [12]. Following radical cystectomy for MIBC, 3–5% of patients develop a metachronous UTUC [13, 14]. Approximately two-thirds of patients who present with UTUCs have invasive disease at diagnosis compared to 15–25% of patients presenting with muscle-invasive bladder tumours [15]. This is probably due to the absence of muscularis propria layer in the upper tract, so tumours are more likely to upstage at an earlier time-point. Approximately 9% of patients present with metastasis [3, 16, 19]. Upper urinary tract UCs have a peak incidence in individuals aged 70–90 years and are twice as common in men [18]. Upper tract UC and bladder cancer exhibit significant differences in the prevalence of common genomic alterations. In individual patients with a history of both tumours, bladder cancer and UTUC were always clonally related. Genomic characterisation of UTUC provides information regarding the risk of bladder recurrence and can identify tumours associated with Lynch syndrome [19]. The Amsterdam criteria are a set of diagnostic criteria used by doctors to help identify families which are likely to have Lynch syndrome [20]. In Lynch-related UTUC, immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis showed loss of protein expression corresponding to the disease-predisposing MMR (mismatch repair) gene mutation in 98% of the samples (46% were microsatellite instable and 54% microsatellite stable) [21]. The majority of tumours develop in MSH2 mutation carriers [28]. Patients identified at high risk for Lynch syndrome should undergo DNA sequencing for patient and family counselling [22,23]. Germline mutations in DNA MMR genes defining Lynch syndrome, are found in 9% of patients with UTUC compared to 1% of patients with bladder cancer, linking UTUC to Lynch syndrome [24]. A study of 115 consecutive UTUC patients, reported that 13.9% screened positive for potential Lynch syndrome and 5.2% had confirmed Lynch syndrome [25]. This is one of the highest rates of undiagnosed genetic disease in urological cancers, which justifies screening of all patients under 60 presenting with UTUC and those with a family history of UTUC (see Figure 1) [26,27] or positive reflexive MMR-test by IHC in sporadic UTUC [24, 28-30].

Figure 1: Selection of patients with UTUC for Lynch syndrome screening during the first medical interview

Risk factors:

A number of environmental factors have been implicated in the development of UTUC [5, 31]. Published evidence in support of a causative role for these factors is not strong, with the exception of smoking and aristolochic acid. Tobacco exposure increases the relative risk of developing UTUC from 2.5 to 7.0 [32–34]. A large population-based study assessing familial clustering in relatives of UC patients, including 229,251 relatives of case subjects and 1,197,552 relatives of matched control subjects, has demonstrated genetic or environmental roots independent of smoking-related behaviours. With more than 9% of the cohort being UTUC patients, clustering was not seen in upper tract disease. This may suggest that the familial clustering of UC is specific to lower tract cancers [35]. In Taiwan and Chile, the presence of arsenic in drinking water has been tentatively linked to UTUC [36,37]. Aristolochic acid, a nitrophenanthrene carboxylic acid produced by Aristolochia plants, which are used worldwide, especially in China and Taiwan [38], exerts multiple effects on the urinary system. Aristolochic acid irreversibly injures renal proximal tubules resulting in chronic tubulointerstitial disease, while the mutagenic properties of this chemical carcinogen lead predominantly to UTUC [38-40]. Aristolochic acid has been linked to bladder cancer, renal cell carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma [41]. Two routes of exposure to aristolochic acid are known: (i) environmental contamination of agricultural products by Aristolochia plants, as reported for Balkan endemic nephropathy [42]; and (ii) ingestion of Aristolochia- based herbal remedies [43,44]. Following bioactivation, aristolochic acid reacts with genomic DNA to form aristolactam-deoxyadenosine adducts [45]; these lesions persist for decades in target tissues, serving as robust biomarkers of exposure [1]. These adducts generate a unique mutational spectrum, characterised by A>T transversions located predominately on the non-transcribed strand of DNA [41, 56]. However, fewer than 10% of individuals exposed to aristolochic acid develop UTUC [40]. Two retrospective series found that aristolochic acid-associated UTUC is more common in females [47, 48]. However, females with aristolochic acid UTUC have a better prognosis than their male counterparts. Consumption of arsenic in drinking water and aristolochia-based herbal remedies together appears to have an additive carcinogenic effect [49]. Alcohol consumption is associated with development of UTUC. A large case-control study (1,569 cases and 506,797 controls) has evidenced a significantly higher risk of UTUC in ever-drinkers compared to neverdrinkers (OR: 1.23; 95% CI: 1.08–1.40, p = 0.001). Compared to never-drinkers, the risk threshold for UTUC was > 15 g of alcohol/day. A dose-response was observed [50]. Differences in the ability to counteract carcinogens may contribute to host susceptibility to UTUC. Some genetic polymorphisms are associated with an increased risk of cancer or faster disease progression that introduces variability in the inter-individual susceptibility to the risk factors previously mentioned. Upper urinary tract UCs may share some risk factors and described molecular pathways with bladder UC [19]. So far, two UTUC-specific polymorphisms have been reported [58]. A history of bladder cancer is associated with a higher risk of developing UTUCs. Patients who undergo ureteral stenting at the time of TURB, including prior to radical cystectomy are at higher risk for upper tract recurrence [52, 53].

Histology and classification:

- Histological types

Upper urinary tract tumours are almost always UCs and pure non-urothelial histology is rare [46, 47]. However, variants are present in approximately 25% of UTUCs [48, 49]. Pure squamous cell carcinoma of the urinary tract is often assumed to be associated with chronic inflammatory diseases and infections arising from urolithiasis [50, 51]. Urothelial carcinoma with divergent squamous differentiation is present in approximately 15% of cases [50]. Keratinising squamous metaplasia of urothelium is a risk factor for squamous cell cancers and therefore mandates surveillance. Upper urinary tract UCs with variant histology are high-grade and have a worse prognosis compared with pure UC [49, 52, 53]. Other variants, although rare, include sarcomatoid and UCs with inverted growth [53]. However, collecting duct carcinomas, which may seem to share similar characteristics with UCs, display a unique transcriptomic signature similar to renal cancer, with a putative cell of origin in the distal convoluted tubules. Therefore, collecting duct carcinomas are considered as renal tumours [54].

STAGING AND CLASSIFICATION SYSTEMS:

- Classification

The classification and morphology of UTUC and bladder carcinoma are similar [2]. However, because of the difficulty in adequate sample acquisition, it is often difficult to distinguish between non-invasive papillary tumours [55], flat lesions (carcinoma in situ [CIS]), and invasive carcinoma. Therefore, histological grade is often used for clinical decision making as it is strongly associated with pathological stage [56].

- Tumour Node Metastasis staging

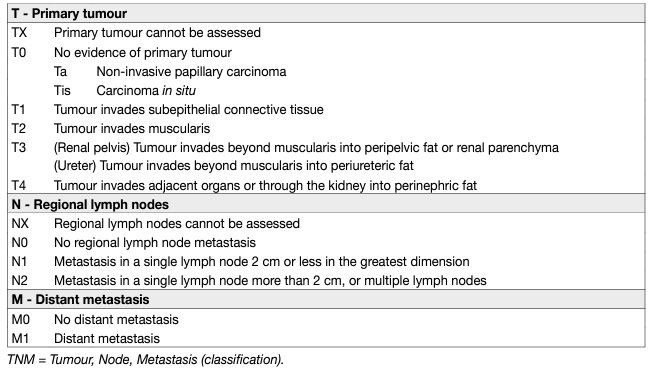

The tumour, node, metastasis (TNM) classification is shown in Table 1 [57]. The regional lymph nodes (LNs) are the hilar and retroperitoneal nodes and, for the mid- and distal ureter, the pelvic nodes. Laterality does not affect N classification.

- Tumour grade

In 2004, the WHO and the International Society of Urological Pathology published a new histological classification of UCs which provides a different patient stratification between individual categories compared to the older 1973 WHO classification [58, 59]. In 2016, an update of the 2004 WHO grading classification was published without major changes [58]. These guidelines are still based on both the 1973 and 2004/2016 WHO classifications since most published data use the 1973 classification [55].

Table 1: TNM classification 2017 for upper tract urothelial cell carcinoma

- Molecular classification of UTUCs

A number of studies focussing on molecular classification have been able to demonstrate genetically distinct groups of UTUC by evaluating DNA, RNA and protein expression. Five molecular subtypes with different gene expression, tumour location and outcome have been identified, but, as yet, it is unclear whether these subtypes will respond differently to treatment [60].

DIAGNOSIS:

- Symptoms

The diagnosis of UTUC may be incidental or symptom related. The most common symptom is visible or nonvisible haematuria (70–80%) [61, 62]. Flank pain, due to clot or tumour tissue obstruction or less often due to local growth, occurs in approximately 20–32% of cases [63]. Systemic symptoms (including anorexia, weight loss, malaise, fatigue, fever, night sweats, or cough) associated with UTUC should prompt evaluation for metastases associated with a worse prognosis [63].

Imaging:

- Computed tomography urography

Computed tomography (CT) urography has the highest diagnostic accuracy of the available imaging techniques [64]. A meta-analysis of 13 studies comprising 1,233 patients revealed a pooled sensitivity of CT urography for UTUC of 92% (CI: 0.85–0.96) and a pooled specificity of 95% (CI: 0.88–0.98) [65]. Rapid acquisition of thin sections allows high-resolution isotropic images that can be viewed in multiple planes to assist with diagnosis without loss of resolution. Epithelial “flat lesions” without mass effect or urothelial thickening are generally not visible with CT. The presence of enlarged LNs is highly predictive of metastases in UTUC [66, 67].

Magnetic resonance urography:

Magnetic resonance (MR) urography is indicated in patients who cannot undergo CT urography, usually when radiation or iodinated contrast media are contraindicated [68]. The sensitivity of MR urography is 75% after contrast injection for tumours < 2 cm [68]. The use of MR urography with gadolinium-based contrast media should be limited in patients with severe renal impairment (< 30 mL/min creatinine clearance), due to the risk of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. Computed tomography urography is more sensitive and specific for the diagnosis and staging of UTUC compared to MR urography [69].

Cystoscopy:

Urethrocystoscopy is an integral part of UTUC diagnosis to rule out concomitant bladder cancer [3,6].

Cytology:

Abnormal cytology may indicate high-grade UTUC when bladder cystoscopy is normal, and in the absence of CIS in the bladder and prostatic urethra [2, 70, 71]. Cytology is less sensitive for UTUC than bladder tumours and should be performed selectively for the affected upper tract [72]. In a recent study, barbotage cytology detected up to 91% of cancers [73]. Barbotage cytology taken from the renal cavities and ureteral lumina is preferred before application of a contrast agent for retrograde ureteropyelography as it may cause deterioration of cytological specimens [74]. Retrograde ureteropyelography remains an option to detect UTUCs [64, 75, 76]. The sensitivity of fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH) for molecular abnormalities characteristic of UTUCs is approximately 50% and therefore its use in clinical practice remains unproven [77, 78].

Diagnostic ureteroscopy:

Flexible ureteroscopy (URS) is used to visualise the ureter, renal pelvis and collecting system and for biopsy of suspicious lesions. Presence, appearance and size of tumour can be determined using URS. In addition, ureteroscopic biopsies can determine tumour grade in more than 90% of cases with a low false-negative rate, regardless of sample size [79]. Undergrading may occur following diagnostic biopsy, making intensive follow-up necessary if kidney-sparing treatment is chosen [56, 80]. Ureteroscopy also facilitates selective ureteral sampling for cytology in situ [76, 81, 82]. Stage assessment using ureteroscopic biopsy is inaccurate. Combining ureteroscopic biopsy grade, imaging findings such as hydronephrosis, and urinary cytology may help in the decision-making process between radical nephroureterectomy (RNU) and kidney-sparing therapy [82, 83]. In a meta-analysis comparing URS vs. no URS prior to RNU, 8/12 studies found an increased risk for intravesical recurrence if URS was performed before RNU [84]. Performing a biopsy at URS was also identified as a risk factor for intravesical recurrence [84]. Technical developments in flexible ureteroscopes and the use of novel imaging techniques improve visualisation and diagnosis of flat lesions [85]. Narrow-band imaging is a promising technique, but results are preliminary [86]. Optical coherence tomography and confocal laser endomicroscopy (Cellvizio®) have been used in vivo to evaluate tumour grade and/or for staging purposes, with a promising correlation with definitive histology in high-grade UTUC [87, 88].

Distant metastases:

Prior to any treatment with curative intent, it is essential to rule out distant metastases. Computed tomography is the diagnostic technique of choice for lung- and abdominal staging for metastases [65]. A SEER analysis shows that approximately 9% of patients present with distant metastases [89].

18F-Fluorodeoxglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography:

A retrospective multi-centre publication on the use of 18F-Fluorodeoxglucose positron emission tomography/ computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT) for the detection of nodal metastasis in 117 surgically-treated UTUC patients reported a promising sensitivity and specificity of 82% and 84%, respectively. Suspicious LNs on FDG-PET/CT were associated with worse recurrence-free survival [90]. These results warrant further validation and comparison with MR urography and CT.

PROGNOSIS:

- Prognostic factors

Many prognostic factors have been identified and can be used to risk-stratify patients in order to decide on the most appropriate local treatment (radical vs. conservative) and discuss peri-operative systemic therapy. Factors can be divided into patient-related factors and tumour-related factors.

- Patient-related factors

- Age and gender

Older age at the time of RNU is independently associated with decreased cancer-specific survival (CSS) [91, 92]. Gender has no impact on prognosis of UTUC [93].

- Ethnicity

One multicentre study in academic centres did not show any difference in outcomes between races [94], but U.S. population-based studies have indicated that African-American patients have worse outcomes than other ethnicities. Whether this is related to access to care or biological and/or patterns of care remains unknown. Another study has demonstrated differences between Chinese and American patients at presentation (risk factor, disease characteristics and predictors of adverse oncologic outcomes) [7].

- Tobacco consumption

Being a smoker at diagnosis increases the risk for disease recurrence, mortality [95, 96] and intravesical recurrence after RNU [97]. There is a close relationship between tobacco consumption and prognosis [98]; smoking cessation improves cancer control [96].

- Surgical delay

A delay between diagnosis of an invasive tumour and its removal may increase the risk of disease progression. Once a decision regarding RNU has been made, the procedure should be carried out within twelve weeks, when possible [99-103].

- Other factors

Comorbidity and performance indices (e.g. American Society of Anesthesiologists [ASA], performance status [PS], and Charlson Comorbidity Index) are also associated with worse survival outcomes across disease stages [104-107]. A higher ASA score confers worse CSS after RNU [108], as does poor PS [109]. Obesity and higher body mass index adversely affect cancer-specific outcomes in patients treated with RNU [110], with potential differences between races [111]. Several blood-based biomarkers have been associated with locally advanced disease and cancer-specific mortality such as high pre-treatment-derived neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio [112-115], low albumin [114, 116], high C-reactive protein [114] or modified Glasgow score [117], high De Ritis ratio (aspartate transaminase/alanine transaminase) [118], altered renal function [114, 119] and high fibrinogen [114, 119].

Tumour-related factors:

- Tumour stage and grade

The main prognostic factors are tumour stage and grade [15, 82, 92, 120]. Upper urinary tract UCs that invade the muscle wall have a poor prognosis. In a large Dutch series of UTUC, 5-year CSS was 86% for non-muscleinvasive tumours, 70% for muscle-invasive organ-confined tumours and 44% for locally-advanced tumours [121]. A SEER contemporary analysis of RNUs for high-risk disease showed that 5-year CSS was 86% for T1N0, 77% for T2N0, 63% for T3N0 and 39% for T4N0/T any N1-3 [122].

- Tumour location, multifocality, size and hydronephrosis

Initial location of the UTUC is a prognostic factor in some studies [123, 124]. After adjustment for the effect of tumour stage, patients with ureteral and/or multifocal tumours seem to have a worse prognosis than patients diagnosed with renal pelvic tumours [125-130]. Hydronephrosis is associated with advanced disease and poor oncological outcome [66, 74, 131]. Increasing tumour size is associated with a higher risk of muscleinvasive and/or non-organ-confined disease, both in ureteral and renal pelvis UTUC. A large multi-institutional retrospective study including 932 RNUs performed for non-metastatic UTUC demonstrated that 2 cm appears to be the best cut-off in identifying patients at risk of harbouring > pT2 UTUC [132]. In a SEER database analysis of 4,657 patients with renal pelvis UTUC, each gain of 1 cm in tumour size was associated with a 1.25-fold higher risk of pT2–T4 histology at RNU [89].

- Variant histology

Pathological variants are associated with worse cancer-specific and overall survival (OS) [133]. Most studied variants are micropapillary [134], squamous [135] and sarcomatoid [134] which are consistently associated with locally-advanced disease and worse outcome.

- Lymph node involvement

Patients with nodal metastasis experience very poor survival after surgery [136]. Lymph node density (cut-off 30%) and extranodal extension are powerful predictors of survival outcomes in N+ UTUC [137-139]. Lymph node dissection (LND) performed at the time of RNU allows for optimal tumour staging, although its curative role remains controversial [138, 140-142].

- Lymphovascular invasion

Lymphovascular invasion (LVI) is present in approximately 20% of invasive UTUCs and is an independent predictor of survival [143-145]. Lymphovascular invasion status should be specifically reported in the pathological reports of all UTUC specimens [143, 146, 147].

- Surgical margins

Positive soft tissue surgical margin is associated with a higher disease recurrence after RNU. Pathologists should look for and report positive margins at the level of ureteral transection, bladder cuff, and around the tumour [148].

- Other pathological factors

Extensive tumour necrosis (> 10% of the tumour area) is an independent prognostic predictor in patients who undergo RNU [149, 150]. In case neoadjuvant treatment was administered, pathological downstaging is associated with better OS [151, 152]. The architecture of UTUC, as determined from pathological examination of RNU specimens, is also a strong prognosticator with sessile growth pattern being associated with worse outcome [153-155]. Concomitant CIS in organ-confined UTUC and a history of bladder CIS are associated with a higher risk of recurrence and cancer-specific mortality [156, 157]. Macroscopic infiltration or invasion of peri-pelvic adipose tissue confers a higher risk of disease recurrence after RNU compared to microscopic infiltration of renal parenchyma [158, 159].

Molecular markers:

Because of the rarity of UTUC, the main limitations of molecular studies are their retrospective design and, for most studies, small sample size. None of the investigated markers have been validated yet to support their introduction in daily clinical decision making [125, 160].

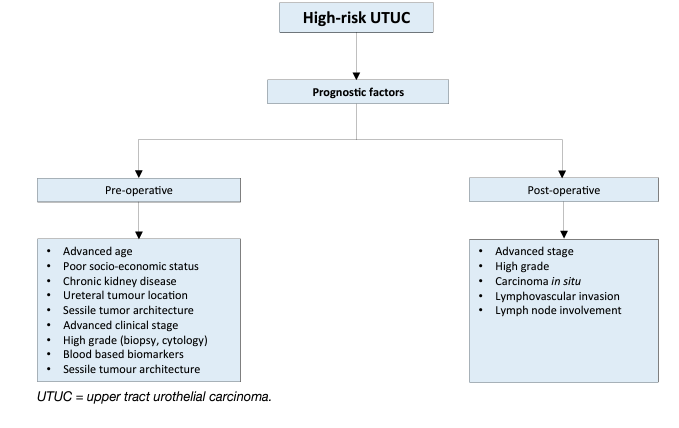

Risk stratification for clinical decision making:

- Low- versus high-risk UTUC

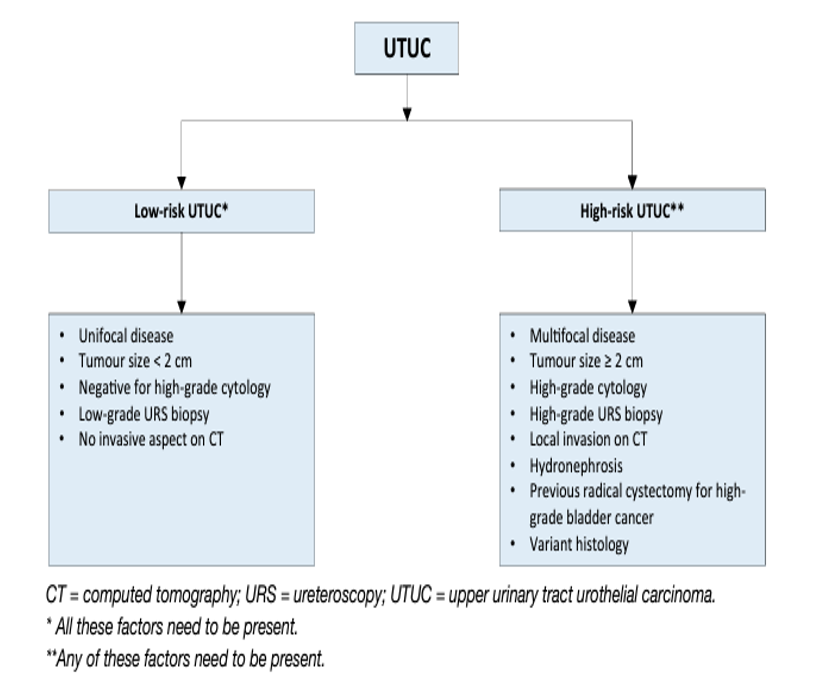

As tumour stage is difficult to assess clinically in UTUC, it is useful to “risk stratify” UTUC between low- and high risk of progression to identify those patients who are more likely to benefit from kidney-sparing treatment and those who should be treated radically [163, 162] (see Figure 2). The factors to consider for risk stratification are presented in Figure 3.

Several new risk stratification models have been assessed to improve upon the dichotomous EAU risk grouping, with the main aim to avoid overtreatment (i.e., better stratify patients eligible for kidney-sparing surgery). Examples include multivariable models with novel clinical characteristics [163] a tumour grade-and stage-based model [164] and a three-tier risk stratification model (i.e., low-, intermediate-, and high risk) [165]. These models need further validation.

Figure 2: UTUC prognostic factors included in prognostic models

Figure 3: Risk stratification of non-metastatic UTUC

Bladder recurrence:

A meta-analysis of available data has identified significant predictors of bladder recurrence after RNU [166]. Three categories of predictors for increased risk of bladder recurrence were identified:

1. Patient-specific factors such as male gender, previous bladder cancer, smoking and preoperative chronic kidney disease.

2. Tumour-specific factors such as positive pre-operative urinary cytology, tumour grade, ureteral location, multifocality, tumour diameter, invasive pT stage, and necrosis [167].

3. Treatment-specific factors such as laparoscopic approach, extravesical bladder cuff removal, and positive surgical margins [166].

In addition, the use of diagnostic URS has been associated with a higher risk of developing bladder recurrence after RNU [168, 169]. Based on low-level evidence only, a single dose of intravesical chemotherapy after diagnostic/therapeutic ureteroscopy of non-metastatic UTUC has been suggested to lower the rate of intravesical recurrence, similarly to that after RNU [166].

DISEASE MANAGEMENT:

- Localised non-metastatic disease

- Kidney-sparing surgery

Kidney-sparing surgery for low-risk UTUC reduces the morbidity associated with radical surgery (e.g., loss of kidney function), without compromising oncological outcomes [170]. In low-risk cancers, it is the preferred approach as survival is similar to that after RNU [170]. This option should therefore be discussed in all low-risk cases, irrespective of the status of the contralateral kidney. In addition, it can also be considered in selected high-risk patients with a serious renal insufficiency or having a solitary kidney.

- Ureteroscopy

Endoscopic ablation should be considered in patients with clinically low-risk cancer [171, 172]. A flexible ureteroscope is useful in the management of pelvicalyceal tumours [173]. The patient should be informed of the need and be willing to comply with an early second-look URS [174] and stringent surveillance; complete tumour resection or destruction is necessary [174]. Nevertheless, a risk of disease progression remains with endoscopic management due to the suboptimal performance of imaging and biopsy for risk stratification and tumour biology [175].

- Percutaneous access

Percutaneous management can be considered for low-risk UTUC in the renal pelvis [171, 176]. This may also be offered for low-risk tumours in the lower caliceal system that are inaccessible or difficult to manage by flexible URS. However, this approach is being used less due to the availability of improved endoscopic tools such as distal-tip deflection of recent ureteroscopes [172, 176]. Moreover, a risk of tumour seeding remains with a percutaneous access [176].

- Ureteral resection

Segmental ureteral resection with wide margins provides adequate pathological specimens for staging and grading while preserving the ipsilateral kidney. Lymphadenectomy can also be performed during segmental ureteral resection [170]. Segmental resection of the proximal two-thirds of ureter is associated with higher failure rates than for the distal ureter [177, 178]. Distal ureterectomy with ureteroneocystostomy are indicated for low-risk tumours in the distal ureter that cannot be removed completely endoscopically and for high-risk tumours when kidney-sparing surgery for renal function preservation is desired (in case of an imperative indication) [179, 177, 180]. A total ureterectomy with an ileal-ureteral substitution is technically feasible, but only in selected cases when a renalsparing procedure is mandatory and the tumour is low risk [181].

- Upper urinary tract instillation of topical agents

The antegrade instillation of BCG or mitomycin C in the upper urinary tract via percutaneous nephrostomy after complete tumour eradication has been studied for CIS after kidney-sparing management [157, 182]. Retrograde instillation through a single J open-ended ureteric stent is also used. Both the antegrade and retrograde approach can be dangerous due to possible ureteric obstruction and consecutive pyelovenous influx during instillation/perfusion. The reflux obtained from a double-J stent has been used but this approach is suboptimal because the drug often does not reach the renal pelvis [183-186]. A systematic review and meta-analysis assessing the oncologic outcomes of patients with papillary UTUC or CIS of the upper tract treated with kidney-sparing surgery and adjuvant endocavitary treatment analysed the effect of adjuvant therapies (i.e., chemotherapeutic agents and/or immunotherapy with BCG) after kidney-sparing surgery for papillary non-invasive (Ta-T1) UTUCs and of adjuvant BCG for the treatment of upper tract CIS, finding no difference between the method of drug administration (antegrade vs. retrograde vs. combined approach) in terms of recurrence, progression, CSS, and OS. Furthermore, the recurrence rates following adjuvant instillations are comparable to those reported in the literature in untreated patients, questioning their efficacy [187]. The analyses were based on retrospective small studies suffering from publication and reporting bias. Recent evidence suggests that early single adjuvant intracavitary instillation of mitomycin C in patients with low-grade UTUC might reduce the risk of local recurrence [188]. This needs to be confirmed in further studies. The authors report limited complications related to the instillations, but propose a retrograde pyelography before instillations are commenced to exclude contrast extravasation. This concept will need further evaluation in a randomised context [188]. A single-arm phase III trial showed that the use of mitomycin-containing reverse thermal gel (UGN-101) instillations in a chemoablation setting via retrograde catheter to the renal pelvis and calyces was associated with a complete response rate in a total of 42 patients (59%) with biopsy-proven low-grade UTUC measuring less than 15 mm. The most frequently reported all-cause adverse events were ureteric stenosis in 31 (44%) of 71 patients, urinary tract infection in 23 (32%), haematuria in 22 (31%), flank pain in 21 (30%), and nausea in 17 (24%). A total of 19 (27%) of 71 patients had drug-related or procedure-related serious adverse events. No deaths were regarded as related to treatment [189].

Management of high-risk non-metastatic UTUC:

- Surgical approach

- Open radical nephroureterectomy

Open RNU with bladder cuff excision is the standard treatment of high-risk UTUC, regardless of tumour location [15]. Radical nephroureterectomy must be performed according to oncological principles preventing tumour seeding [15].

- Minimal invasive radical nephroureterectomy

Retroperitoneal metastatic dissemination and metastasis along the trocar pathway following manipulation of large tumours in a pneumoperitoneal environment have been reported in few cases [190, 191]. Several precautions may lower the risk of tumour spillage:

- avoid entering the urinary tract;

- avoid direct contact between instruments and the tumour;

- perform the procedure in a closed system. Avoid morcellation of the tumour and use an endobag for tumour extraction;

- the kidney and ureter must be removed en bloc with the bladder cuff;

- invasive or large (T3/T4 and/or N+/M+) tumours are contraindications for minimal-invasive RNU as the outcome is worse compared to an open approach [192, 193].

Laparoscopic RNU is safe in experienced hands when adhering to strict oncological principles. There is a tendency towards equivalent oncological outcomes after laparoscopic or open RNU [191, 194-197]. One prospective randomised study has shown that laparoscopic RNU is inferior to open RNU for non-organ-confined UTUC. However, this was a small trial (n = 80), which was likely underpowered [193]. Oncological outcomes after RNU have not changed significantly over the past three decades despite staging and surgical refinements [198]. In a population-based data set, a hospital volume of > 6 patients per year treated with RNU showed improvement of short-term outcomes (30- and 90-day mortality) and overall long-term survival [199]. A robot-assisted laparoscopic approach can be considered with recent data suggesting oncologic equivalence with the other approaches [200-202].

- Management of bladder cuff

Resection of the distal ureter and its orifice is performed because there is a considerable risk of tumour recurrence in this area and in the bladder [166, 177, 203-205]. Several techniques have been considered to simplify distal ureter resection, including the pluck technique, stripping, transurethral resection of the intramural ureter, and intussusception. None of these techniques has convincingly been shown to be equal to complete bladder cuff excision [9, 203, 204].

- Lymph node dissection

The use of a LND template is likely to have a greater impact on patient survival than the number of removed LNs [206]. Template-based and completeness of LND improves CSS in patients with muscle-invasive disease and reduces the risk of local recurrence [207]. Even in clinically [208] and pathologically [209] node-negative patients, LND improves survival. The risk of LN metastasis increases with advancing tumour stage [141]. Lymph node dissection appears to be unnecessary in cases of TaT1 UTUC because of the low risk of LN metastasis [210-213], however, tumour staging is inaccurate pre-operatively; therefore, a template-based LND should be offered to all patients who are scheduled for RNU for high-risk non-metastatic UTUC. The templates for LND have been described [207, 214, 215].

Peri-operative chemotherapy:

- Neoadjuvant chemotherapy

In patients treated prior to losing their renal reserve several retrospective studies evaluating the role of neoadjuvant chemotherapy have shown promising pathological downstaging and complete response rates [151, 216-219]. No RCTs have been published yet but prospective data from a phase II trial showed that the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy was associated with a 14% pathological complete response rate for highgrade UTUC [220]. In addition, final pathological stage was < ypT1 in more than 60% of included patients with acceptable toxicity profile. In a systematic review and meta-analysis comprising more than 800 patients, neoadjuvant chemotherapy has shown a pathologic partial response of 43% and a downstaging in 33% of patients, and also an OS and CSS survival benefit compared with RNU alone [221]. Furthermore, neoadjuvant chemotherapy has been shown to result in lower disease recurrence and mortality rates compared to RNU alone without compromising the use of definitive surgical treatment [218, 222-224].

- Adjuvant chemotherapy

- Chemotherapy

A phase III prospective randomised trial (n = 261) evaluating the benefit of adjuvant gemcitabine-platinum combination chemotherapy initiated within 90 days after RNU vs. surveillance has reported a significant improvement in disease-free survival in patients with pT2–pT4, N (any) or LN-positive (pT any, N1–3) M0 UTUC [225]. The main limitation of using adjuvant chemotherapy for advanced UTUC remains the limited ability to deliver full dose cisplatin-based regimen after RNU, given that this surgical procedure is likely to impact renal function [226, 227]. In a retrospective study histological variants of UTUC exhibit different survival rates and adjuvant chemotherapy was only associated with an OS benefit in patients with pure UC [228].

- Immunotherapy

In a phase 3, multicentre, double-blind RCT involving patients with high-risk muscle-invasive UC who had undergone radical surgery, adjuvant nivolumab improved disease-free survival compared to placebo in the intention-to-treat population (20.8 vs 10.8 months) and among patients with a PD-L1 expression level of 1% or more [229]. The median survival free from recurrence outside the urothelial tract in the intention-to-treat population was 22.9 months with nivolumab and 13.7 months with placebo. Treatment-related adverse events > grade 3 occurred in 17.9% of the nivolumab group and 7.2% of the placebo group. The subgroup of patients with UTUC in this study needs further analysis to better understand the effect of adjuvant nivolumab for high-risk muscle-invasive UC after RNU.

Adjuvant radiotherapy after radical nephroureterectomy:

Adjuvant radiation therapy has been suggested to control loco-regional disease after surgical removal. The data remains controversial and insufficient for conclusions [230-233]. Moreover, its added value to chemotherapy remains questionable [232].

Post-operative bladder instillation:

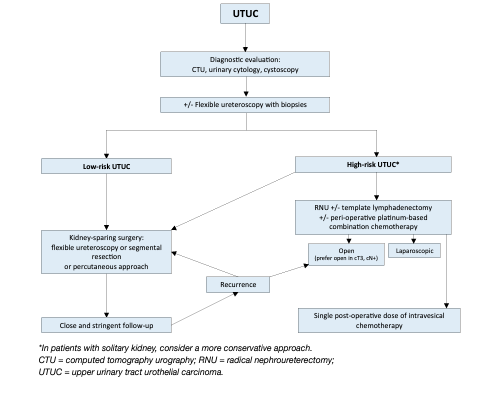

The rate of bladder recurrence after RNU for UTUC is 22–47% [162, 203]. Two prospective randomised trials [234, 235] and two meta-analyses [236, 237] have demonstrated that a single post-operative dose of intravesical chemotherapy (mitomycin C, pirarubicin) 2–10 days after surgery reduces the risk of bladder tumour recurrence within the first years post-RNU. Prior to instillation, a cystogram might be considered in case of any concerns about drug extravasation. Based on current evidence it is unlikely that additional instillations beyond one peri-operative instillation of chemotherapy further substantially reduces the risk of intravesical recurrence [238]. Whilst there is no direct evidence supporting the use of intravesical instillation of chemotherapy after kidney-sparing surgery, single dose chemotherapy might be effective in that setting as well. Management is outlined in Figures 4 and 5. One low-level evidence study suggested that bladder irrigation might reduce the risk of bladder recurrence after RNU [239].

Figure 4: Proposed flowchart for the management of UTUC

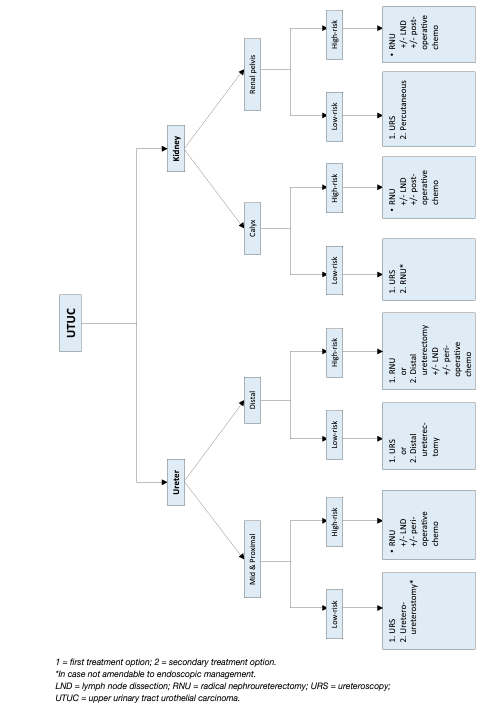

Figure 5: Surgical treatment according to location and risk status

Metastatic disease:

- Radical nephroureterectomy

The role of RNU in the treatment of patients with metastatic UTUC has recently been explored in several observational studies [240-243]. Although evidence remains very limited, RNU may be associated with cancer specific [240, 242, 243] and OS benefit in selected patients, especially those fit enough to receive cisplatin-based chemotherapy [241, 242]. It is noteworthy that these benefits may be limited to those patients with only one metastatic site [242]. Nonetheless, given the high risk of bias of the observational studies addressing RNU for metastatic UTUC, indications for RNU in this setting should mainly be reserved for palliative patients, aimed at controlling symptomatic disease [11, 95].

- Metastasectomy

There is no UTUC-specific study supporting the role of metastasectomy in patients with advanced disease. However, several reports including both UTUC and bladder cancer patients suggested that resection of metastatic lesions could be safe and oncologically beneficial in selected patients with a life expectancy of more than 6 months [244-246]. This was confirmed in the most recent and largest study to date [247]. In patients with metastases limited to lung and/or lymph nodes, whose disease responded to systemic chemotherapy, metastasectomy can improve oncological outcomes in individual cases [248]. Nonetheless, in the absence of data from RCTs, patients should be evaluated on an individual basis and the decision to perform a metastasectomy (surgically) should be made following a shared decision-making process with the patient.

- Systemic treatments

- First-line setting

- Patients fit enough to tolerate cisplatin-based combination chemotherapy

Data from the bladder cancer literature and from small, single-centre UTUC studies suggest that platinumbased combination chemotherapy, especially cisplatin, is efficacious as first-line treatment of metastatic UTUC. Cisplatin-containing combination chemotherapy is standard in advanced or metastatic patients fit enough to tolerate cisplatin [249]. A number of cisplatin-containing chemotherapy regimens are acceptable although gemcitabine and cisplatin is the most widely used. A retrospective analysis of three RCTs showed that primary tumour location in the lower- or upper urinary tract had no impact on progression-free survival (PFS) or OS in patients with locally advanced or metastatic UC treated with platinum-based combination chemotherapy [250]. The efficacy of immunotherapy using programmed death-1 (PD1) or programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitors has been evaluated in the first-line setting for the treatment of cisplatin-fit patients with metastatic UC, including those with UTUC [251]. The combination of platinum-based chemotherapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors have not resulted in positive significant survival advantages and are not currently recommended [252].

- Patients fit for carboplatin (but unfit for cisplatin-based combination chemotherapy)

Carboplatin-based chemotherapy is recommended in patients unfit for cisplatin [249]. Carboplatin with gemcitabine is the preferred regimen [253].

- Maintenance therapy after first-line platinum-based treatment

Platinum-based chemotherapy followed by maintenance avelumab is preferred to upfront immune checkpoint inhibitors in both PD-L1 biomarker positive and negative patients. Data from a phase III RCT showed that the use of avelumab maintenance therapy after 4 to 6 cycles of gemcitabine plus cisplatin or carboplatin (started within 10 weeks of completion of first-line platinum-based chemotherapy) significantly prolonged OS as compared to best supportive care alone in those patients with advanced or metastatic UC who did not progress during, or responded to, first-line chemotherapy (HR 0.69; 95% CI 0.56–0.86) [254, 255]. An increase in median OS from 14 to 21 months was observed with avelumab. Although no subgroup analysis based on tumour location was available in this study, almost 30% of the included patients had UTUC. Similarly, in a phase II study comprising 108 patients with metastatic UC achieving at least stable disease on first-line platinum-based chemotherapy, maintenance pembrolizumab improved PFS compared to placebo (5.4 vs. 3.0 months) [256].

- Immunotherapy in cisplatin-unfit patients

Pembrolizumab or atezolizumab are alternative choices for patients who are PD-L1 positive and not eligible for cisplatin-based chemotherapy, although RCTs failed to show significant superiority compared with chemotherapy [252, 257]. Final data from randomised trials with durvalumab are similar with no OS benefit [258]. Biomarkers (SP142 for atezolizumab; 22C3 for pembrolizumab) should be used to match the drug, as recommended by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) [259, 260]. In a single-arm phase II trial (n = 370) of cisplatin-ineligible UC, pembrolizumab monotherapy was associated with an objective response rate of 26% in 69 metastatic UTUC patients [261]. In the overall cohort, a PD-L1 expression of 10% was associated with a greater response rate to pembrolizumab. Treatment-related toxicity was in line with previous studies. In a single-arm phase II trial (n = 119) of cisplatin-ineligible UC, atezolizumab monotherapy was associated with an objective response rate of 39% in 33 (28%) metastatic UTUC patients [262]. Median OS in the overall cohort was 15.9 months and treatment-related toxicity was in line with previous studies. Data from a phase III RCT including 1,213 patients with metastatic cisplatin-eligible and cisplatin-ineligible UC, of which 312 (26%) were diagnosed with UTUC, showed that the combination of atezolizumab with platinum-based chemotherapy prolonged both PFS and OS [257]. No subgroup analysis based on tumour location was performed in this study.

- Second-line setting

- Immunotherapy

A phase III RCT including 542 patients who received prior platinum-based chemotherapy for advanced UC showed that pembrolizumab could decrease the risk of death compared to second-line chemotherapy (the investigator’s choice of paclitaxel, docetaxel, or vinflunine); median OS: 10.3 months for pembrolizumab and 7.4 months for chemotherapy, HR 0.73, 95% CI: 0.59–0.91 [263]. Responses were more frequent and durable for pembrolizumab compared with chemotherapy (21% vs. 11%). In the UTUC subgroup (n = 75, 13.8%), the OS benefit seemed larger (50%). The IMVigor211 trial explored atezolizumab in PD-L1 biomarker positive tumours in patients with tumours which have relapsed after platinum-based therapy and failed to show a significant OS advantage [264]. In a phase II study, 48 patients with platinum-refractory UC (18/48 patients with UTUC) were treated with cabozantinib. There was one complete response and 7 partial responses (objective response rate 19%, 95% CI: 9–34). Median PFS was 3.7 months (95% CI: 3–6) [265]. Other immunotherapies such as nivolumab [266], avelumab [287, 288] and durvalumab [269] have shown objective response rates ranging from 17.8% [269] to 19.6% [286] and median OS ranging from 7.7 months to 18.2 months in patients with platinum-resistant metastatic UC. These results were obtained from singlearm phase I or II trials only and the number of UTUC patients included in these studies was only specified for avelumab (n = 7/15.9%) without any subgroup analysis based on primary tumour location [286]. The immunotherapy combination of nivolumab plus ipilimumab has shown significant anti-tumour activity with objective response rate up to 38% in a phase I/II multicentre trial including 78 patients with metastatic UC progressing after platinum-based chemotherapy [270]. Although UTUC patients were included in this trial, no subgroup analysis was available. Other immunotherapy combinations may be effective in the second-line setting but data are currently limited [271].

- Novel agents

Fibroblast growth factor receptors (FGFR) inhibition Erdafitinib, a pan-FGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor of FGFR1–4, was associated with a 40% response rate in a phase II trial in 99 patients with locally advanced or metastatic UC who progressed after first-line chemotherapy and harboured a FGFR DNA genomic alterations (FGFR2 or 3 mutations, or FGFR3 fusions) [272]. This study included 23 UTUC patients with visceral metastases showing a 43% response rate.

- Antibody drug conjugates (ADC)

A phase II study enrolled 89 patients (of whom 43% had UTUC) with metastatic UC progressing after therapy with PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitors. All patients received the antibody–drug conjugate enfortumab vedotin. The objective response rate was 52%, 20% of patients achieved complete response [273].

- Third-line setting

In an open-label phase II trial a total of 108 patients with metastatic UC with progression on platinum-based and checkpoint inhibitors were treated with the antibody-drug conjugate sacituzumab govitecan. The objective response rate was 27%, with median duration of response 7.2 months, median PFS 5.4 months and OS 10.9 months. The site of primary UC is not mentioned in the publication [274]. A pre-planned subgroup analysis from the phase III RANGE trial assessed the impact on outcomes and safety of ramucirumab added to docetaxel after disease progression on both platinum and immune checkpoint inhibitors therapy [275]. Median PFS was 3.15 months on ramucirumab/docetaxel vs 2.73 months on placebo/ docetaxel (HR = 0.786, 95%, CI: 0.404–1.528, p = 0.4877). This trend for ramucirumab benefit occurred despite the ramucirumab arm having a higher percentage of patients with poorer prognosis. However, these findings need confirmation by further studies, as this analysis is limited by patient numbers and an imbalance in the treatment arms.

FOLLOW-UP:

The risk of recurrence and death evolves during the follow-up period after surgery [296]. A direct relationship exists between event-free follow-up and survival probability after RNU [122]. Stringent follow-up is mandatory to detect metachronous bladder tumours (probability increases over time [277]), local recurrence, and distant metastases. Surveillance regimens are based on cystoscopy and urinary cytology [8, 277]. Bladder recurrence is not considered a distant recurrence. When kidney-sparing surgery is performed, the ipsilateral UUT requires careful and long-term follow-up due to the high risk of disease recurrence [173, 278, 279] and progression to RNU beyond 5 years [280]. Despite endourological improvements, follow-up after kidney-sparing management is difficult and frequent, and repeated endoscopic procedures are necessary. Following kidney-sparing surgery, and as done in bladder cancer, an early repeated (second look) ureteroscopy within 6 to 8 weeks after primary endoscopic treatment has been proposed, but is not yet routine practice [249, 174].

REFERENCES:

1. Siegel, R.L., et al. Cancer Statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin, 2021. 71: 7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33433946/

2. Babjuk, M., et al., EAU Guidelines on Non-muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer (T1, T1 and CIS), in EAU Guidelines, Edn. presented at the 37th EAU Annual Congress Amsterdam. 2022, EAU Guidelines Office, Arnhem, The Netherlands. https://uroweb.org/guideline/non-muscle-invasive-bladder-cancer/

3. Soria, F., et al. Epidemiology, diagnosis, preoperative evaluation and prognostic assessment of upper-tract urothelial carcinoma (UTUC). World J Urol, 2017. 35: 379. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27604375/

4. Almås, B., et al. Higher than expected and significantly increasing incidence of upper tract urothelial carcinoma. A population based study. World J Urol, 2021. 39: 3385. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33420812/

5. Green, D.A., et al. Urothelial carcinoma of the bladder and the upper tract: disparate twins. J Urol, 2013. 189: 1214. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23023150/

6. Cosentino, M., et al. Upper urinary tract urothelial cell carcinoma: location as a predictive factor for concomitant bladder carcinoma. World J Urol, 2013. 31: 141. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22552732/

7. Singla, N., et al. A Multi-Institutional Comparison of Clinicopathological Characteristics and Oncologic Outcomes of Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinoma in China and the United States. J Urol, 2017. 197: 1208. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27887951/

8. Xylinas, E., et al. Multifocal Carcinoma In Situ of the Upper Tract Is Associated With High Risk of Bladder Cancer Recurrence. Eur Urol, 2012. 61: 1069. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22402109/

9. Li, W.M., et al. Oncologic outcomes following three different approaches to the distal ureter and bladder cuff in nephroureterectomy for primary upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma. Eur Urol, 2010. 57: 963. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20079965/

10. Miller, E.B., et al. Upper tract transitional cell carcinoma following treatment of superficial bladder cancer with BCG. Urology, 1993. 42: 26. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8328123/

11. Herr, H.W. Extravesical tumor relapse in patients with superficial bladder tumors. J Clin Oncol, 1998. 16: 1099. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9508196/

12. Nishiyama, N., et al. Upper tract urothelial carcinoma following intravesical bacillus Calmette-Guérin therapy for nonmuscle-invasive bladder cancer: Results from a multi-institutional retrospective study. Urol Oncol, 2018. 36: 306.e9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29550096/

13. Sanderson, K.M., et al. Upper urinary tract tumour after radical cystectomy for transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: an update on the risk factors, surveillance regimens and treatments. BJU Int, 2007. 100: 11. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17428248/

14. Ayyathurai, R., et al. Monitoring of the upper urinary tract in patients with bladder cancer. Indian J Urol, 2011. 27: 238. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21814316/

15. Margulis, V., et al. Outcomes of radical nephroureterectomy: a series from the Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinoma Collaboration. Cancer, 2009. 115: 1224. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19156917/

16. Aziz, A., et al. Stage Migration for Upper Tract Urothelial Cell Carcinoma. Clin Genitourin Cancer, 2021. 19: e184. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33153919/

17. Browne, B.M., et al. An Analysis of Staging and Treatment Trends for Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinoma in the National Cancer Database. Clin Genitourin Cancer, 2018. 16: e743. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29506950/

18. Shariat, S.F., et al. Gender differences in radical nephroureterectomy for upper tract urothelial carcinoma. World J Urol, 2011. 29: 481. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20886219/

19. Audenet, F., et al. Clonal Relatedness and Mutational Differences between Upper Tract and Bladder Urothelial Carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res, 2019. 25: 967. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30352907/

20. Umar, A., et al. Revised Bethesda Guidelines for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome) and microsatellite instability. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2004. 96: 261. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14970275/

21. Therkildsen, C., et al. Molecular subtype classification of urothelial carcinoma in Lynch syndrome. Mol Oncol, 2018. 12: 1286. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29791078/

22. Roupret, M., et al. Upper urinary tract urothelial cell carcinomas and other urological malignancies involved in the hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (lynch syndrome) tumor spectrum. Eur Urol, 2008. 54: 1226. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18715695/

23. Acher, P., et al. Towards a rational strategy for the surveillance of patients with Lynch syndrome (hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer) for upper tract transitional cell carcinoma. BJU Int, 2010. 106: 300. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20553255/

24. Ju, J.Y., et al. Universal Lynch Syndrome Screening Should be Performed in All Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol, 2018. 42: 1549. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30148743/

25. Metcalfe, M.J., et al. Universal Point of Care Testing for Lynch Syndrome in Patients with Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinoma. J Urol, 2018. 199: 60. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28797715/

26. Pradere, B., et al. Lynch syndrome in upper tract urothelial carcinoma: significance, screening, and surveillance. Curr Opin Urol, 2017. 27: 48. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27533503/

27. Audenet, F., et al. A proportion of hereditary upper urinary tract urothelial carcinomas are misclassified as sporadic according to a multi-institutional database analysis: proposal of patientspecific risk identification tool. BJU Int, 2012. 110: E583. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22703159/

28. Gayhart, M.G., et al. Universal Mismatch Repair Protein Screening in Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol, 2020. 154: 792. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32789450/

29. Schneider, B., et al. Loss of Mismatch-repair Protein Expression and Microsatellite Instability in Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinoma and Clinicopathologic Implications. Clin Genitourin Cancer, 2020. 18: e563. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32340874/

30. Ito, T., et al. Prevalence of Lynch syndrome among patients with upper urinary tract carcinoma in a Japanese hospital-based population. Jpn J Clin Oncol, 2020. 50: 80. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31665498/

31. Colin, P., et al. Environmental factors involved in carcinogenesis of urothelial cell carcinomas of the upper urinary tract. BJU Int, 2009. 104: 1436. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19689473/

32. Dickman K.G., et al. Epidemiology and Risk Factors for Upper Urinary Urothelial Cancers, In: Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinoma. 2015, Springer: New York, NY, USA.

33. McLaughlin, J.K., et al. Cigarette smoking and cancers of the renal pelvis and ureter. Cancer Res, 1992. 52: 254. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1728398/

34. Crivelli, J.J., et al. Effect of smoking on outcomes of urothelial carcinoma: a systematic review of the literature. Eur Urol, 2014. 65: 742. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23810104/

35. Martin, C., et al. Familial Cancer Clustering in Urothelial Cancer: A Population-Based Case-Control Study. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2018. 110: 527. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29228305/

36. Chen C-H., et al. Arsenics and urothelial carcinoma. In: Health Hazards of Environmental Arsenic Poisoning from Epidemic to Pandemic, Chen C.J., Editor. 2011, World Scientific: Taipei.

https://tmu.pure.elsevier.com/en/publications/health-hazards-of-environmental-arsenic-poisoningfrom-epidemic-t

37. López, J.F., et al. Arsenic exposure is associated with significant upper tract urothelial carcinoma health care needs and elevated mortality rates. Urol Oncol, 2020. 38: 638.e7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32088105/

38. Grollman, A.P. Aristolochic acid nephropathy: Harbinger of a global iatrogenic disease. Environ Mol Mutagen, 2013. 54: 1. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23238808/

39. Aristolochic acids. Rep Carcinog, 2011. 12: 45. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21822318/

40. Cosyns, J.P. Aristolochic acid and ‘Chinese herbs nephropathy’: a review of the evidence to date. Drug Saf, 2003. 26: 33. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12495362/

41. Rosenquist, T.A., et al. Mutational signature of aristolochic acid: Clue to the recognition of a global disease. DNA Repair (Amst), 2016. 44: 205. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27237586/

42. Jelakovic, B., et al. Aristolactam-DNA adducts are a biomarker of environmental exposure to aristolochic acid. Kidney Int, 2012. 81: 559. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22071594/

43. Chen, C.H., et al. Aristolochic acid-associated urothelial cancer in Taiwan. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2012. 109: 8241. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22493262/

44. Nortier, J.L., et al. Urothelial carcinoma associated with the use of a Chinese herb (Aristolochia fangchi). N Engl J Med, 2000. 342: 1686. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10841870/

45. Sidorenko, V.S., et al. Bioactivation of the human carcinogen aristolochic acid. Carcinogenesis, 2014. 35: 1814. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24743514/

46. Hoang, M.L., et al. Mutational signature of aristolochic acid exposure as revealed by whole-exome sequencing. Sci Transl Med, 2013. 5: 197ra102. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23926200/

47. Huang, C.C., et al. Gender Is a Significant Prognostic Factor for Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinoma: A Large Hospital-Based Cancer Registry Study in an Endemic Area. Front Oncol, 2019. 9: 157. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30949449/

48. Xiong, G., et al. Aristolochic acid containing herbs induce gender-related oncological differences in upper tract urothelial carcinoma patients. Cancer Manag Res, 2018. 10: 6627. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30584358/

49. Chen, C.H., et al. Additive Effects of Arsenic and Aristolochic Acid in Chemical Carcinogenesis of Upper Urinary Tract Urothelium. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 2021. 30: 317. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33277322/

50. Zaitsu, M., et al. Alcohol consumption and risk of upper-tract urothelial cancer. Cancer Epidemiol, 2017. 48: 36. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28364670/

51. Roupret, M., et al. Genetic variability in 8q24 confers susceptibility to urothelial carcinoma of the upper urinary tract and is linked with patterns of disease aggressiveness at diagnosis. J Urol, 2012. 187: 424. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22177160/

52. Kiss, B., et al. Stenting Prior to Cystectomy is an Independent Risk Factor for Upper Urinary Tract Recurrence. J Urol, 2017. 198: 1263. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28603003/

53. Sountoulides, P., et al. Does Ureteral Stenting Increase the Risk of Metachronous Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinoma in Patients with Bladder Tumors? A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Urol, 2021. 205: 956. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33284711/

54. Sakano, S., et al. Impact of variant histology on disease aggressiveness and outcome after nephroureterectomy in Japanese patients with upper tract urothelial carcinoma. Int J Clin Oncol, 2015. 20: 362. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24964974/

55. Soukup, V., et al. Prognostic Performance and Reproducibility of the 1973 and 2004/2016 World Health Organization Grading Classification Systems in Non-muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer: A European Association of Urology Non-muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer Guidelines Panel Systematic Review. Eur Urol, 2017. 72: 801. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28457661/

56. Subiela, J.D., et al. Diagnostic accuracy of ureteroscopic biopsy in predicting stage and grade at final pathology in upper tract urothelial carcinoma: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol, 2020. 46: 1989. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32674841/

57. Brierley, J.D., et al. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours. 8th ed. 2016.

https://www.uicc.org/resources/tnm-classification-malignant-tumours-8th-edition

58. Moch H, H.P., et al. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs. Fourth edition. 2016, Lyon.

https://publications.iarc.fr/Book-And-Report-Series/Who-Classification-Of-Tumours/WHOClassification-Of-Tumours-Of-The-Urinary-System-And-Male-Genital-Organs-2016

59. Sauter, G., et al. Tumours of the urinary system: non-invasive urothelial neoplasias, In: WHO classification of classification of tumours of the urinary system and male genital organs. 2004, IARC Press: Lyon.

https://isbndata.org/978-92-832-2415-0/pathology-and-genetics-of-tumours-of-the-urinarysystemand-male-genital-organs-iarc-who-classification-of-tumours

60. Fujii, Y., et al. Molecular classification and diagnostics of upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma. Cancer Cell, 2021. 39: 793. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34129823/

61. Inman, B.A., et al. Carcinoma of the upper urinary tract: predictors of survival and competing causes of mortality. Cancer, 2009. 115: 2853. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19434668/

62. Cowan, N.C. CT urography for hematuria. Nat Rev Urol, 2012. 9: 218. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22410682/

63. Baard, J., et al. Contemporary patterns of presentation, diagnostics and management of upper tract urothelial cancer in 101 centres: the Clinical Research Office of the Endourological Society Global upper tract urothelial carcinoma registry. Curr Opin Urol, 2021. 31: 354. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34009177/

64. Cowan, N.C., et al. Multidetector computed tomography urography for diagnosing upper urinary tract urothelial tumour. BJU Int, 2007. 99: 1363. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17428251/

65. Janisch, F., et al. Diagnostic performance of multidetector computed tomographic (MDCTU) in upper tract urothelial carcinoma (UTUC): a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Urol, 2020. 38: 1165. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31321509/

66. Verhoest, G., et al. Predictive factors of recurrence and survival of upper tract urothelial carcinomas. World J Urol, 2011. 29: 495. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMC3526475/

67. Millán-Rodríguez, F., et al. Conventional CT signs in staging transitional cell tumors of the upper urinary tract. Eur Urol, 1999. 35: 318. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10087395/

68. Takahashi, N., et al. Gadolinium enhanced magnetic resonance urography for upper urinary tract malignancy. J Urol, 2010. 183: 1330. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20171676/

69. Razavi, S.A., et al. Comparative effectiveness of imaging modalities for the diagnosis of upper and lower urinary tract malignancy: a critically appraised topic. Acad Radiol, 2012. 19: 1134. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22717592/

70. Witjes, J.A., et al. Hexaminolevulinate-guided fluorescence cystoscopy in the diagnosis and follow-up of patients with non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: review of the evidence and recommendations. Eur Urol, 2010. 57: 607. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20116164/

71. Rosenthal DL, W.E., et al. The Paris System for Reporting Urinary Cytology. 2016, Switzerland.

https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9783319228631

72. Messer, J., et al. Urinary cytology has a poor performance for predicting invasive or high-grade upper-tract urothelial carcinoma. BJU Int, 2011. 108: 701. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21320275/

73. Malm, C., et al. Diagnostic accuracy of upper tract urothelial carcinoma: how samples are collected matters. Scand J Urol, 2017. 51: 137. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28385123/

74. Messer, J.C., et al. Multi-institutional validation of the ability of preoperative hydronephrosis to predict advanced pathologic tumor stage in upper-tract urothelial carcinoma. Urol Oncol, 2013. 31: 904. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21906967/

75. Wang, L.J., et al. Diagnostic accuracy of transitional cell carcinoma on multidetector computerized tomography urography in patients with gross hematuria. J Urol, 2009. 181: 524. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19100576/

76. Lee, K.S., et al. MR urography versus retrograde pyelography/ureteroscopy for the exclusion of upper urinary tract malignancy. Clin Radiol, 2010. 65: 185. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20152273/

77. McHale, T., et al. Comparison of urinary cytology and fluorescence in situ hybridization in the detection of urothelial neoplasia: An analysis of discordant results. Diagn Cytopathol, 2019. 47: 282. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30417563/

78. Jin, H., et al. A comprehensive comparison of fluorescence in situ hybridization and cytology for the detection of upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore), 2018. 97: e13859. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30593189/

79. Rojas, C.P., et al. Low biopsy volume in ureteroscopy does not affect tumor biopsy grading in upper tract urothelial carcinoma. Urol Oncol, 2013. 31: 1696. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22819696/

80. Smith, A.K., et al. Inadequacy of biopsy for diagnosis of upper tract urothelial carcinoma: implications for conservative management. Urology, 2011. 78: 82. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21550642/

81. Ishikawa, S., et al. Impact of diagnostic ureteroscopy on intravesical recurrence and survival in patients with urothelial carcinoma of the upper urinary tract. J Urol, 2010. 184: 883. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20643446/

82. Clements, T., et al. High-grade ureteroscopic biopsy is associated with advanced pathology of upper-tract urothelial carcinoma tumors at definitive surgical resection. J Endourol, 2012. 26: 398. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22192113/

83. Brien, J.C., et al. Preoperative hydronephrosis, ureteroscopic biopsy grade and urinary cytology can improve prediction of advanced upper tract urothelial carcinoma. J Urol, 2010. 184: 69. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20478585/

84. Sharma, V., et al. The Impact of Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinoma Diagnostic Modality on Intravesical Recurrence after Radical Nephroureterectomy: A Single Institution Series and Updated Meta-Analysis. J Urol, 2021. 206: 558. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33908802/

85. Bus, M.T., et al. Optical diagnostics for upper urinary tract urothelial cancer: technology, thresholds, and clinical applications. J Endourol, 2015. 29: 113. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25178057/

86. Knoedler, J.J., et al. Advances in the management of upper tract urothelial carcinoma: improved endoscopic management through better diagnostics. Ther Adv Urol, 2018. 10: 421. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30574202/

87. Breda, A., et al. Correlation Between Confocal Laser Endomicroscopy (Cellvizio((R))) and Histological Grading of Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinoma: A Step Forward for a Better Selection of Patients Suitable for Conservative Management. Eur Urol Focus, 2018. 4: 954. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28753800/

88. Bus, M.T., et al. Optical Coherence Tomography as a Tool for In Vivo Staging and Grading of Upper Urinary Tract Urothelial Carcinoma: A Study of Diagnostic Accuracy. J Urol, 2016. 196: 1749. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27475968/

89. Collà Ruvolo, C., et al. Tumor Size Predicts Muscle-invasive and Non-organ-confined Disease in Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinoma at Radical Nephroureterectomy. Eur Urol Focus, 2021. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33737024/

90. Voskuilen, C.S., et al. Diagnostic Value of (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography with Computed Tomography for Lymph Node Staging in Patients with Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinoma. Eur Urol Oncol, 2020. 3: 73. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31591037/

91. Kim, H.S., et al. Association between demographic factors and prognosis in urothelial carcinoma of the upper urinary tract: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget, 2017. 8: 7464. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27448978/

92. Collà Ruvolo, C., et al. Incidence and Survival Rates of Contemporary Patients with Invasive Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinoma. Eur Urol Oncol, 2020. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33293235/

93. Mori, K., et al. Differential Effect of Sex on Outcomes after Radical Surgery for Upper Tract and Bladder Urothelial Carcinoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Urol, 2020. 204: 58. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31995432/

94. Matsumoto, K., et al. Racial differences in the outcome of patients with urothelial carcinoma of the upper urinary tract: an international study. BJU Int, 2011. 108: E304. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21507184/

95. Simsir, A., et al. Prognostic factors for upper urinary tract urothelial carcinomas: stage, grade, and smoking status. Int Urol Nephrol, 2011. 43: 1039. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21547471/

96. Rink, M., et al. Impact of smoking on oncologic outcomes of upper tract urothelial carcinoma after radical nephroureterectomy. Eur Urol, 2013. 63: 1082. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22743166/

97. Xylinas, E., et al. Impact of smoking status and cumulative exposure on intravesical recurrence of upper tract urothelial carcinoma after radical nephroureterectomy. BJU Int, 2014. 114: 56. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24053463/

98. Shigeta, K., et al. A Novel Risk-based Approach Simulating Oncological Surveillance After Radical Nephroureterectomy in Patients with Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinoma. Eur Urol Oncol, 2020. 3: 756. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31395480/

99. Sundi, D., et al. Upper tract urothelial carcinoma: impact of time to surgery. Urol Oncol, 2012. 30: 266. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20869888/

100. Gadzinski, A.J., et al. Long-term outcomes of immediate versus delayed nephroureterectomy for upper tract urothelial carcinoma. J Endourol, 2012. 26: 566. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21879886/

101. Lee, J.N., et al. Impact of surgical wait time on oncologic outcomes in upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma. J Surg Oncol, 2014. 110: 468. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25059848/

102. Waldert, M., et al. A delay in radical nephroureterectomy can lead to upstaging. BJU Int, 2010. 105: 812. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19732052/

103. Xia, L., et al. Impact of surgical waiting time on survival in patients with upper tract urothelial carcinoma: A national cancer database study. Urol Oncol, 2018. 36: 10 e15. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29031419/

104. Kluth, L.A., et al. Predictors of survival in patients with disease recurrence after radical nephroureterectomy. BJU Int, 2014. 113: 911. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24053651/

105. Aziz, A., et al. Comparative analysis of comorbidity and performance indices for prediction of oncological outcomes in patients with upper tract urothelial carcinoma who were treated with radical nephroureterectomy. Urol Oncol, 2014. 32: 1141. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24856977/

106. Chromecki, T.F., et al. Chronological age is not an independent predictor of clinical outcomes after radical nephroureterectomy. World J Urol, 2011. 29: 473. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21499902/

107. Tanaka, N., et al. Patient characteristics and outcomes in metastatic upper tract urothelial carcinoma after radical nephroureterectomy: the experience of Japanese multi-institutions. BJU Int, 2013. 112: E28. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23795795/

108. Berod, A.A., et al. The role of American Society of Anesthesiologists scores in predicting urothelial carcinoma of the upper urinary tract outcome after radical nephroureterectomy: results from a national multi-institutional collaborative study. BJU Int, 2012. 110: E1035. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22568669/

109. Carrion, A., et al. Intraoperative prognostic factors and atypical patterns of recurrence in patients with upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma treated with laparoscopic radical nephroureterectomy. Scand J Urol, 2016. 50: 305. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26926709/

110. Ehdaie, B., et al. Obesity adversely impacts disease specific outcomes in patients with upper tract urothelial carcinoma. J Urol, 2011. 186: 66. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21571333/

111. Yeh, H.C., et al. Interethnic differences in the impact of body mass index on upper tract urothelial carcinoma following radical nephroureterectomy. World J Urol, 2021. 39: 491. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32318857/

112. Dalpiaz, O., et al. Validation of the pretreatment derived neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic factor in a European cohort of patients with upper tract urothelial carcinoma. Br J Cancer, 2014. 110: 2531. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24691424/

113. Vartolomei, M.D., et al. Is neutrophil-to-lymphocytes ratio a clinical relevant preoperative biomarker in upper tract urothelial carcinoma? A meta-analysis of 4385 patients. World J Urol, 2018. 36: 1019. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29468284/

114. Mori, K., et al. Prognostic value of preoperative blood-based biomarkers in upper tract urothelial carcinoma treated with nephroureterectomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Urol Oncol, 2020. 38: 315. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32088103/

115. Zheng, Y., et al. Combination of Systemic Inflammation Response Index and Platelet-toLymphocyte Ratio as a Novel Prognostic Marker of Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinoma After Radical Nephroureterectomy. Front Oncol, 2019. 9: 914. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31620369/

116. Liu, J., et al. The prognostic significance of preoperative serum albumin in urothelial carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biosci Rep, 2018. 38. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29685957/

117. Soria, F., et al. Prognostic value of the systemic inflammation modified Glasgow prognostic score in patients with upper tract urothelial carcinoma (UTUC) treated with radical nephroureterectomy: Results from a large multicenter international collaboration. Urol Oncol, 2020. 38: 602.e11. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32037197/

118. Mori, K., et al. Prognostic role of preoperative De Ritis ratio in upper tract urothelial carcinoma treated with nephroureterectomy. Urol Oncol, 2020. 38: 601.e17. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32127252/

119. Xu, H., et al. Pretreatment elevated fibrinogen level predicts worse oncologic outcomes in upper tract urothelial carcinoma. Asian J Androl, 2020. 22: 177. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31169138/

120. Mbeutcha, A., et al. Prognostic factors and predictive tools for upper tract urothelial carcinoma: a systematic review. World J Urol, 2017. 35: 337. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27101100/

121. van Doeveren, T., et al. Rising incidence rates and unaltered survival rates for primary upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma: a Dutch population-based study from 1993 to 2017. BJU Int, 2021. 128: 343. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33690922/

122. Rosiello, G., et al. Contemporary conditional cancer-specific survival after radical nephroureterectomy in patients with nonmetastatic urothelial carcinoma of upper urinary tract. J Surg Oncol, 2020. 121: 1154. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32107785/

123. Yafi, F.A., et al. Impact of tumour location versus multifocality in patients with upper tract urothelial carcinoma treated with nephroureterectomy and bladder cuff excision: a homogeneous series without perioperative chemotherapy. BJU Int, 2012. 110: E7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22177329/

124. Ouzzane, A., et al. Ureteral and multifocal tumours have worse prognosis than renal pelvic tumours in urothelial carcinoma of the upper urinary tract treated by nephroureterectomy. Eur Urol, 2011. 60: 1258. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21665356/

125. Lughezzani, G., et al. Prognostic factors in upper urinary tract urothelial carcinomas: a comprehensive review of the current literature. Eur Urol, 2012. 62: 100. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22381168/

126. Kaczmarek, K., et al. Survival differences of patients with ureteral versus pelvicalyceal tumours: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Med Sci, 2021. 17: 603. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34025829/

127. Chromecki, T.F., et al. The impact of tumor multifocality on outcomes in patients treated with radical nephroureterectomy. Eur Urol, 2012. 61: 245. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21975249/

128. Williams, A.K., et al. Multifocality rather than tumor location is a prognostic factor in upper tract urothelial carcinoma. Urol Oncol, 2013. 31: 1161. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23415596/

129. Hurel, S., et al. Influence of preoperative factors on the oncologic outcome for upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma after radical nephroureterectomy. World J Urol, 2015. 33: 335. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24810657/

130. Lwin, A.A., et al. Urothelial Carcinoma of the Renal Pelvis and Ureter: Does Location Make a Difference? Clin Genitourin Cancer, 2020. 18: 45. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31786118/

131. Ito, Y., et al. Preoperative hydronephrosis grade independently predicts worse pathological outcomes in patients undergoing nephroureterectomy for upper tract urothelial carcinoma. J Urol, 2011. 185: 1621. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21419429/

132. Foerster, B., et al. The Performance of Tumor Size as Risk Stratification Parameter in Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinoma (UTUC). Clin Genitourin Cancer, 2021. 19: 272.e1. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33046411/

133. Mori, K., et al. Prognostic Value of Variant Histology in Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinoma Treated with Nephroureterectomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Urol, 2020. 203: 1075. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31479406/

134. Zamboni, S., et al. Incidence and survival outcomes in patients with upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma diagnosed with variant histology and treated with nephroureterectomy. BJU Int, 2019. 124: 738. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30908835/

135. Yu, J., et al. Impact of squamous differentiation on intravesical recurrence and prognosis of patients with upper tract urothelial carcinoma. Ann Transl Med, 2019. 7: 377. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31555691/

136. Pelcovits, A., et al. Outcomes of upper tract urothelial carcinoma with isolated lymph node involvement following surgical resection: implications for multi-modal management. World J Urol, 2020. 38: 1243. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31388818/