Urological Infections

Peri-Procedural Antibiotic Prophylaxis

Part 3

Comprehensive Review Article

Prof. Dr. Semir. A. Salim. Al Samarrai

The General Principles of Peri-Procedural Antibiotic Prophylaxis:

- Definition of infectious complications

The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) and the CDC have both presented similar definitions recommended for the evaluation of infectious complications [1,2].

- Non-antibiotic measures for asepsis

There are a number of non-antibiotic measures designed to reduce the risk of surgical site infection (SSI), many are historically part of the routine of surgery. The effectiveness of measures tested by RCTs are summarized in systematic reviews conducted by the Cochrane Wounds Group (http://wounds.cochrane.org/news/reviews). Urological surgeons and the institutions in which they work should consider and monitor maintenance of an aseptic environment to reduce risk of infection from pathogens within patients (microbiome) and from outside the patient (nosocomial/healthcare-associated). This should include use of correct methods of instrument cleaning and sterilisation, frequent and thorough cleaning of operating rooms and recovery areas and thorough disinfection of any contamination. The surgical team should prepare to perform surgery by effective hand washing [3], donning of appropriate protective clothing and maintenance of asepsis. These measures should continue as required in recovery and ward areas. Patients should be encouraged to shower pre-operatively, but use of chlorhexidine soap does not appear to be beneficial [4]. Although evidence quality is low, any required hair removal appears best done by clipping, rather than shaving, just prior to incision [5]. Mechanical bowel preparation should not be used as evidence review suggests harm not benefit [6,7]. There is some weak evidence that skin preparation using alcoholic solutions or chlorhexidine result in a lower rate of SSI than iodine solutions [8]. Studies on the use of plastic adherent drapes showed no evidence of benefit in reducing SSI [9].

- Detection of bacteriuria prior to urological procedures

Identifying bacteriuria prior to diagnostic and therapeutic procedures aims to reduce the risk of infectious complications by controlling any pre-operative detected bacteriuria and to optimise antimicrobial coverage in conjunction with the procedure. A systematic review of the evidence identified eighteen studies comparing the diagnostic accuracy of different index tests (dipstick, automated microscopy, dipslide culture and flow cytometry), with urine culture as the reference standard [10]. The systematic review concluded that none of the alternative urinary investigations for the diagnosis of bacteriuria in adult patients prior to urological interventions can currently be recommended as an alternative to urine culture [10].

- Choice of agent

Urologists should have knowledge of local pathogen prevalence for each type of procedure, their antibiotic susceptibility profiles and virulence in order to establish written local guidelines. These guidelines should cover the five modalities identified by the ECDC following a systematic review of the literature [11]. The agent should ideally not be one that may be required for treatment of infection. When risk of skin wound infection is low or absent, an aminoglycoside (gentamicin) should provide cover against likely uropathogens provided the eGFR is > 20 mL/min; second generation cephalosporins are an alternative [12]. Recent urine culture results including presence of any multi-resistant organisms, drug allergy, history of C. difficile associated diarrhoea, recent antibiotic exposure, evidence of symptomatic infection pre-procedure and serum creatinine should be checked.

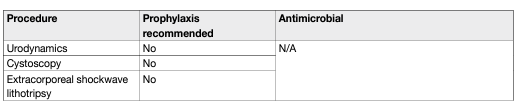

Specific procedures and evidence question:

An updated literature search from February 2017 (cut-off of last update) to June 2021 identified RCTs, systematic reviews and meta-analyses that investigated the benefits and harms of using antibiotic prophylaxis prior to specific urological procedures. The available evidence enabled the EAU Guidelines 2022-panel to make recommendations concerning urodynamics, cystoscopy, stone procedures (extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy [ESWL], ureteroscopy and percutaneous nephrolithotomy [PCNL]), transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) and transurethral resection of the bladder (TURB). The general evidence question was: Does antibiotic prophylaxis reduce the rate of post-operative symptomatic UTI in patients undergoing each named procedure?

- Urodynamics

The literature search identified one systematic review for antibiotic prophylaxis in women only [13]. This included three RCTs (n=325) with the authors reporting that prophylactic antibiotics reduced the risk of bacteriuria but not clinical UTI after urodynamics [13]. A previous Cochrane review identified nine RCTs enrolling 973 patients with overall low quality and high or unclear risks of bias [14]. The outcome of clinical UTI was reported in four trials with no benefit found for antibiotic prophylaxis vs. placebo [RR (95%CI) 0.73 (0.52-1.03)]. A meta-analysis of nine trials showed that use of antibiotics reduced the rate of post-procedural bacteriuria [RR (95%CI) 0.35 (0.22-0.56)] [14].

- Cystoscopy

Three systematic reviews and meta-analyses [15–17] and one additional RCT [18] on cystoscopy for stent removal were identified. Garcia-Perdomo et al., included seven RCTs with a total of 3,038 participants. The outcome of symptomatic UTI was measured by five trials of moderate overall quality and meta-analysis showed a benefit for using antibiotic prophylaxis [RR (95%CI) 0.53 (0.31 – 0.90)]; ARR 1.3% (from 2.8% to 1.5%) with a NNT of 74 [16]. This benefit was not seen if only the two trials with low risk of bias were used in the meta-analysis. Carey et al., included seven RCTs with 5,107 participants. Six trials were included in metaanalysis of the outcome of symptomatic bacteriuria which found benefit for use of antibiotic prophylaxis [RR (95%CI) 0.34 (0.27 – 0.47)]; ARR 3.4% (from 6% to 2.6%) with NNT of 28 [15]. Zeng et al., included twenty RCTs and two quasi-RCTs with a total of 7,711 participants. The outcome of symptomatic UTI was measured by eleven RCTs of low overall quality and meta-analysis showed a possible benefit for using antibiotic prophylaxis [RR (95% CI) 0.49 (0.28 – 0.86)] [17]. For systemic UTI, antibiotic prophylaxis showed no effect compared with placebo or no treatment in five RCTs [RR (95% CI) 1.12 (0.38 – 3.32)]. However, prophylactic antibiotics may increase bacterial resistance [(RR (95% CI) 1.73 (1.04 – 2.87)]. Given the low absolute risk of post-procedural UTI in well-resourced countries, the high number of procedures being performed, and the high risk of contributing to increasing antimicrobial resistance the EAU Guidelines 2022-panel consensus was to strongly recommend not to use antibiotic prophylaxis in patients undergoing urethrocystoscopy (flexible or rigid).

Interventions for urinary stone treatment:

- Extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy

For patients without bacteriuria undergoing ESWL two systematic reviews and meta-analyses were identified with latest search dates of November 2011 and October 2012, respectively [19,20] and one further RCT [21]. Lu et al., included nine RCTs with a total of 1,364 patients and found no evidence of benefit in terms of reducing the rate of post-procedural fever or bacteriuria [19]. Mrkobrada et al., included eight RCTs with a total of 940 participants and found no evidence of benefit for antibiotic prophylaxis to reduce rate of fever or trial-defined infection [20]. A RCT with 274 patients and severe risk of bias found no reduction in fever at up to one-week post-procedure using a single dose of levofloxacin 500 mg and no difference in the rate of bacteriuria [21]. Another RCT (n=600) again with severe risk of bias found no difference in UTI and positive urine culture rates at two weeks post-procedure using 200 mg ofloxacin post-operatively for three-days vs. placebo [22]. For patients with bacteriuria or deemed at high risk of complications one RCT comparing the use of ofloxacin or trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole for three days prior and four days subsequent to ESWL in 56 patients with ureteric stents was identified [23]. They found no difference in rate of clinical UTI at seven days (no events) and no difference in post-ESWL bacteriuria.

- Ureteroscopy

One updated systematic review and meta-analysis with last search date of June 2017 was identified and included eleven RCTs with 4,591 patients [24]. The meta-analysis found that post-operative pyuria and bacteriuria rates were significantly lower in patients who received pre-operative antibiotic prophylaxis pyuria (OR: 0.42, 95% CI 0.25–0.69 and OR: 0.25, 95% CI 0.11–0.58, respectively). Five studies assessed postoperative febrile UTI (fUTI) and found no difference in the rate of fUTIs between patients who did or did not receive antibiotic prophylaxis (OR: 0.82, 95% CI 0.40– 1.67). However, a significantly higher risk of postoperative fever in the pre-operative antibiotic prophylaxis group (OR: 1.75, 95% CI 1.22–2.50) was reported. A subgroup analysis on the type of pre-operative antibiotic prophylaxis found no difference between a single dose of oral vs. intravenous antibiotics [24]. A RCT comparing different ciprofloxacin-based antibiotic prophylaxis regimens on the incidence of SIRS after URS found there was no difference in the incidences of SIRS between the regimens including the zero-dose regime [25]. However, there was a greater risk of SIRS in patients who did not receive antibiotic prophylaxis when the stone size was > 200 mm2 [25]. Another RCT comparing the use of two oral doses of 3 g fosfomycine tromethamine before surgery to standard of care did not find any difference in the incidence of infections, bacteriuria or fever [26].

- Percutaneous neprolithotomy (PNL)

The largest systematic review and meta-analysis performed, latest search date April 2019, included 1,549 patients in thirteen comparative studies on antibiotic prophylaxis strategies for PNL [27]. Compared with a single dose before surgery pre-operative antibiotic prophylaxis significantly reduced post-operative sepsis and fever (OR 0.31, 95%CI 0.20-0.50 and OR 0.26, 95%CI 0.14-0.48, respectively) [27]. Similarly, the rate of positive pelvic urine and positive stones culture were reduced when pre-operative prophylaxis was given. There was no difference in sepsis rates between patients receiving or not receiving post-operative prophylaxis; however, patients who received post-operative antibiotic prophylaxis had more fever [27]. Four RCTs with overall low risk of bias comparing different antibiotic regimes in PNL were identified [28–31]. Seyrek et al., compared the rate of SIRS following PNL in 191 patients receiving either a combination of sulbactam/ampicillin or cefuroxime. There was no difference in SIRS or urosepsis rates [28]. Tuzel et al., investigated single dose ceftriaxone vs. ceftriaxone and subsequently an oral third-generation cephalosporin until after nephrostomy catheter withdrawal at mean of three days in 73 participants undergoing PNL. They found no difference in rate of infectious complications between the two antibiotic regimens [29]. Taken et al., compared the administration of 1 g ceftriaxone and 1 g cefazoline both administered 30 minutes before surgery and continued till nephrostomy removal. They found no difference in terms of SRIS or sepsis between groups [31]. Omar et al., compared ciprofloxacin 200 mg i.v. vs. 2 mg cefotaxime 30 minutes before and 12 hours after surgery and found a higher rate of fever in the cefotaxime group [30]. However, these results remain limited by the high risk of bias and the lack of data regarding post-operative infection. These studies give moderate evidence that a single dose of a suitable agent was adequate for prophylaxis against clinical infection after PNL.

- Transurethral resection of the prostate

A systematic review of 39 RCTs with search date up to 2009 was identified [32]. The update search to February 2017 did not reveal any further relevant studies. Of the 39 RCTs reviewed by Dahm et al., six trials involving 1,666 men addressed the risk of septic episodes, seventeen trials reported procedure related fever and 39 investigated bacteriuria. Use of prophylactic antibiotics compared to placebo showed a relative risk reduction (95% CI) for septic episode of 0.51 (0.27-0.96) with ARR of 2% (3.4% – 1.4%) and a NNT of 50. The risk reduction (95% CI) for fever was 0.64 (0.55-0.75) and 0.37 (0.32-0.41) for bacteriuria.

- Transurethral resection of the bladder

One systematic review which included seven trials with a total of 1,725 participants was identified [33]. Antimicrobial prophylaxis showed no significant effect on post-operative UTIs [OR (95% CI) 1.55 (0.73 – 3.31)] and asymptomatic bacteriuria [OR (95% CI) 0.43 (0.18 – 1.04)] [33]. The review did not attempt sub-group analysis according to presence of risk factors for post-operative infection such as tumour size. Risk factors for development of post-operative UTIs were evaluated only by three of the included studies and most of the parameters were analysed by no more than one study. A RCT (n=100) comparing oral fosfomycin 3 g (the night before surgery) vs. intravenous cefoxitin 2 g (30 minutes pre- and 24 hours post-surgery) on post-operative UTIs found that a single oral administration of fosfomycin was non-inferior to intravenous administration of cefoxitin in the prevention of post-TURB UTI, even in patients considered at higher risk [34].

- Midurethral slings

One systematic review and meta-analysis identified one study assessing the role of pre-operative antibiotics for midurethral sling surgery alone [35]. The study was halted due to low rate of infectious outcomes seen at the first scheduled interim analysis. The study enrolled 29 women in the antibiotic prophylaxis (cefazolin) group and 30 in the placebo group with a total follow-up of six months. No statistically significant difference between the cefazolin and placebo groups, with respect to wound infections [1 (3.3%) vs. 0 (0%)] or bacteriuria [3 (10%) vs. 1 (3.5%)] was found [35].

- Renal tumour ablation

One systematic review publication date 2018 included 6,952 patients across 51 studies [36]. Infectious complications were reported in 74 patients including fever (60.8%), abscess (21.6%) and UTI (8.1%). Prophylactic antibiotic use was reported in 5.4% of patients, but it was not possible to study its association to infectious complications due to lack of reporting.

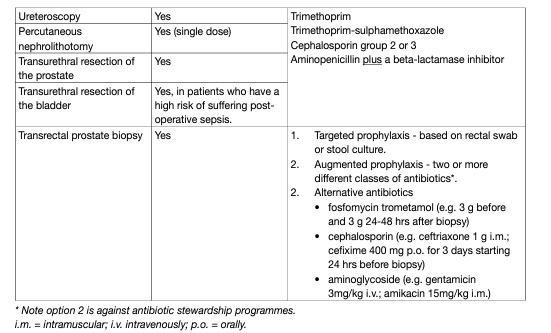

Prostate biopsy:

- Transperineal prostate biopsy

A total of seven randomised studies including 1,330 patients compared the impact of biopsy route on infectious complications. Infectious complications were significantly higher following transrectal biopsy (37 events among 657 men) compared to transperineal biopsy (22 events among 673 men), [RR (95% CIs) 1.81 (1.09 to 3.00)] [37]. In addition, a systematic review including 165 studies with 162,577 patients described sepsis rates of 0.1% and 0.9% for transperineal and transrectal biopsies, respectively [38]. Finally, a population-based study from the UK (n=73,630) showed lower re-admission rates for sepsis in patients who had transperineal vs. transrectal biopsies (1.0% vs. 1.4%, respectively) [39]. The available evidence demonstrates that the transrectal approach should be abandoned in favour of the transperineal approach despite any possible logistical challenges. To date, no RCT has been published investigating different antibiotic prophylaxis regimens for transperineal prostate biopsy.

- Transrectal prostate biopsy

Meta-analysis of eight RCTs including 1,786 men showed that use of a rectal povidone-iodine preparation before biopsy, in addition to antimicrobial prophylaxis, resulted in a significantly lower rate of infectious complications [RR (95% CIs) 0.55 (0.41 to 0.72)] [37]. Single RCTs showed no evidence of benefit for perineal skin disinfection [40], but reported an advantage for rectal povidone-iodine preparation before biopsy compared to after biopsy [41]. A meta-analysis of four RCTs including 671 men evaluated the use of rectal preparation by enema before transrectal biopsy. No significant advantage was found regarding infectious complications [RR (95% CIs) 0.96 (0.64 to 1.54)] [37]. A meta-analysis of 26 RCTs with 3,857 patients found no evidence that use of peri-prostatic injection of local anaesthesia resulted in more infectious complications than no injection [RR (95% CIs) 1.07 (0.77 to 1.48)] [37]. A meta-analysis of nine RCTs including 2,230 patients found that extended biopsy templates showed comparable infectious complications to standard templates [RR (95% CIs) 0.80 (0.53 to 1.22)] [37]. Additional meta-analyses found no difference in infections complications regarding needle guide type (disposable vs. reusable), needle type (coaxial vs. non-coaxial), needle size (large vs. small), and number of injections for peri-prostatic nerve block (standard vs. extended) [37]. A meta-analysis of eleven studies with 1,753 patients showed significantly reduced infections after transrectal prostate biopsy when using antimicrobial prophylaxis as compared to placebo/control [RR (95% CIs) 0.56 (0.40 to 0.77)] [42]. Fluoroquinolones have been traditionally used for antibiotic prophylaxis in this setting; however, overuse and misuse of fluoroquinolones has resulted in an increase in fluoroquinolone resistance. In addition, the European Commission has implemented stringent regulatory conditions regarding the use of fluoroquinolones resulting in the suspension of the indication for peri-operative antibiotic prophylaxis including prostate biopsy [43]. A systematic review and meta-analysis on antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of infectious complications following prostate biopsy concluded that in countries where fluoroquinolones are allowed as antibiotic prophylaxis, a minimum of a full one-day administration, as well as targeted therapy in case of fluoroquinolone resistance, or augmented prophylaxis (combination of two or more different classes of antibiotics) is recommended [42]. In countries where use of fluoroquinolones are suspended cephalosporins or aminoglycosides can be used as individual agents with comparable infectious complications based on meta-analysis of two RCTs [42]. A meta-analysis of three RCTs reported that fosfomycin trometamol was superior to fluoroquinolones [RR (95% CIs) 0.49 (0.27 to 0.87)] [42], but routine general use should be critically assessed due to the relevant infectious complications reported in non-randomised studies [44]. Another possibility is the use of augmented prophylaxis without fluoroquinolones, although no standard combination has been established to date. Finally, targeted prophylaxis based on rectal swap/stool culture is plausible, but no RCTs are available on non-fluoroquinolones. See figure 1 for prostate biopsy workflow to reduce infections complications.

Table 1: Suggested regimens for antimicrobial prophylaxis prior to urological procedures.

Figure 1: Prostate biopsy workflow to reduce infectious complications

1. No RCTs available, but reasonable intervention.

2. Be informed about local antimicrobial resistance.

3. Banned by European Commission due to side effects.

4. Contradicts principles of Antimicrobial Stewardship.

5. Fosfomycin trometamol (3 RCTs), cephalosporins (2 RCTs), aminoglycosides (2 RCTs).

6. Only one RCT comparing targeted and augmented prophylaxis.

7. Originally introduced to use alternative antibiotics in case of fluoroquinolone resistance.

8. Various schemes: fluoroquinolone plus aminoglycoside (3 RCTs); and fluoroquinolone plus cephalosporin (1 RCT).

9. Significantly inferior to targeted and augmented prophylaxis.

Suggested workflow on how to reduce post biopsy infections. GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High certainty: (⊕⊕⊕⊕) very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: (⊕⊕⊕⊖) moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: (⊕⊕⊖⊖) confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: (⊕⊖⊖⊖) very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. Figure reproduced from Pilatz et al., [479] with permission from Elsevier. i.m. = intramuscular; i.v. intravenously; p.o. = orally.

REFERENCES:

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Annual Epidemiological Report 2016 – Healthcareassociated infections acquired in intensive care units. 2016. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/healthcare-associated-infections-intensive-care-units-annualepidemiological-0

- CDC. Procedure-associated Module 9: Surgical Site Infection (SSI) Event. 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/9pscssicurrent.pdf

- Tanner, J., et al. Surgical hand antisepsis to reduce surgical site infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2016: CD004288. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26799160/

- Webster, J., et al. Preoperative bathing or showering with skin antiseptics to prevent surgical site infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2015: CD004985. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25927093/

- Webster, J., et al. Preoperative bathing or showering with skin antiseptics to prevent surgical site infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2015: CD004985. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25927093/

- Tanner, J., et al. Preoperative hair removal to reduce surgical site infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2011: CD004122. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22071812/

- Arnold, A., et al. Preoperative Mechanical Bowel Preparation for Abdominal, Laparoscopic, and Vaginal Surgery: A Systematic Review. J Minim Invasive Gynecol, 2015. 22: 737. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25881881/

- Guenaga, K.F., et al. Mechanical bowel preparation for elective colorectal surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2011: CD001544. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21901677/

- Dumville, J.C., et al. Preoperative skin antiseptics for preventing surgical wound infections after clean surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2015: CD003949. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25897764/

- Webster, J., et al. Use of plastic adhesive drapes during surgery for preventing surgical site infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2015: CD006353. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25901509/

- Bonkat, G., et al. Non-molecular Methods to Detect Bacteriuria Prior to Urological Interventions: A Diagnostic Accuracy Systematic Review. Eur Urol Focus, 2017. 3: 535. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29627196/

- ECDC. Systematic review and evidence-based guidance on perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis. 2013. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/portal/files/media/en/publications/Publications/Perioperative%20 antibiotic%20prophylaxis%20-%20June%202013.pdf Antibacterial prophylaxis in surgery: 2 – Urogenital, obstetric and gynaecological surgery. Drug Ther Bull, 2004. 42: 9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38220205/

- Benseler, A., et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for urodynamic testing in women: a systematic review. Int Urogynecol J, 2021. 32: 27. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32845398/

- Foon, R., et al. Prophylactic antibiotics to reduce the risk of urinary tract infections after urodynamic studies [Systematic Review]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2012. 10: 10. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23076941/

- Carey, M.M., et al. Should We Use Antibiotic Prophylaxis for Flexible Cystoscopy? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Urol Int, 2015. 95: 249. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26138144/

- Garcia-Perdomo, H.A., et al. Efficacy of antibiotic prophylaxis in cystoscopy to prevent urinary tract infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Braz J Urol, 2015. 41: 412. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26200530/

- Zeng, S., et al. Antimicrobial agents for preventing urinary tract infections in adults undergoing cystoscopy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2019. 2: CD012305. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30789676/

- Bradshaw, A.W., et al. Antibiotics are not necessary during routine cystoscopic stent removal: A randomized controlled trial at UC San Diego. Urol Ann, 2020. 12: 373. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33776335/

- Lu, Y., et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for shock wave lithotripsy in patients with sterile urine before treatment may be unnecessary: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Urol, 2012. 188: 441. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/52059642/

- Mrkobrada, M., et al. CUA Guidelines on antibiotic prophylaxis for urologic procedures. Can Urol Assoc J, 2015. 9: 13. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25737749/

- Hsieh, C.H., et al. The Effectiveness of Prophylactic Antibiotics with Oral Levofloxacin against Post-Shock Wave Lithotripsy Infectious Complications: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Surg Infect, 2016. 17: 346. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26910613/

- Shafi, H., et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis in the prevention of urinary tract infection in patients with sterile urine before extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy. Caspain J Intern Med, 2018. 9: 296. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30197776/

- Liker, Y., et al. The role of antibiotics in patients with increased risk of infection during extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) treatment. Marmara Med J, 1996. 9: 174. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26377368/

- Deng, T., et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis in ureteroscopic lithotripsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. BJU Int, 2018. 122: 29. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29232047/

- Zhao, Z., et al. Recommended antibiotic prophylaxis regimen in retrograde intrarenal surgery: evidence from a randomised controlled trial. BJU Int, 2019. 124: 496. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31136070/.

- Qiao, L.D., et al. Evaluation of perioperative prophylaxis with fosfomycin tromethamine in ureteroscopic stone removal: an investigator-driven prospective, multicenter, randomized, controlled study. Int Urol Nephrol, 2018. 50: 427. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29290000/

- Yu, J., et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis in perioperative period of percutaneous nephrolithotomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. World J Urol, 2020. 38: 1685. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31562533/

- Seyrek, M., et al. Perioperative prophylaxis for percutaneous nephrolithotomy: Randomized study concerning the drug and dosage. J Endourol, 2012. 26: 1431. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22612061/

- Tuzel, E., et al. Prospective comparative study of two protocols of antibiotic prophylaxis in percutaneous nephrolithotomy. J Endourol, 2013. 27: 172. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22908891/

- Omar, M., et al. Ciprofloxacin infusion versus third generation cephalosporin as a surgical prophylaxis for percutaneous nephrolithotomy: a randomized study. Centr Eur J Urol, 2019. 72: 57. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31011442/

- Taken, K., et al. Comparison of Ceftriaxone and Cefazolin Sodium Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Terms of SIRS/ Urosepsis Rates in Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy. J Urol Surg, 2019. 6: 111. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/333236810

- Dahm, P., et al. Evidence-based Urology. BMJ Books London, 2010: 50.

- Bausch, K., et al. Antimicrobial Prophylaxis for Postoperative Urinary Tract Infections in Transurethral Resection of Bladder Tumors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Urol, 2021. 205: 987. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33284673/

- Yang, J., et al. Prospective, randomized controlled study of the preventive effect of fosfomycin tromethamine on post-transurethral resection of bladder tumor urinary tract infection. Int J Urol, 2018. 25: 894. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29999216/

- Sanaee, M.S., et al. Urinary tract infection prevention after midurethral slings in pelvic floor reconstructive surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand, 2019. 98: 1514. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31112286/

- Crawford, D., et al. Infectious Outcomes from Renal Tumor Ablation: Prophylactic Antibiotics or Not? Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol, 2018. 41: 1573. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30062444/

- Pradere, B., et al. Non-antibiotic Strategies for the Prevention of Infectious Complications following Prostate Biopsy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Urol, 2021. 205: 653. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33026903/

- Bennett, H.Y., et al. The global burden of major infectious complications following prostate biopsy. Epidemiol Infect, 2016. 144: 1784. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26645476/

- Berry, B., et al. Comparison of complications after transrectal and transperineal prostate biopsy: a national population-based study. BJU Int, 2020. 126: 97. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32124525/

- Taher, Y., et al. MP48-11 Prospective randomized controlled study to assess the effect of perineal region cleansing with povidone iodine before transrectal needle biopsy of the prostate on infectious complications. Urology 84, S306 https://www.auajournals.org/doi/full/10.1016/j.juro.2015.02.1685

- Yu, L., et al. Impact of insertion timing of iodophor cotton ball on the control of infection complications after transrectal ultrasound guided prostate biopsy. Nat Med J China, 2014. 94: 609. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24762693/

- Pilatz, A., et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of infectious complications following prostate biopsy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Urol, 2020. 204: 224. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32105195/

- European Medicines Agency. Disabling and potentially permanent side effects lead to suspension or restrictions of quinolone and fluoroquinolone antibiotics. Quinolone and fluoroquinolone Article-31 referral, 2019. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/referral/quinolone-fluoroquinolone-article-31-referral-disablingpotentially-permanent-side-effects-lead_en.pdf

- Carignan, A., et al. Effectiveness of fosfomycin tromethamine prophylaxis in preventing infection following transrectal ultrasound-guided prostate needle biopsy: Results from a large Canadian cohort. J Glob Antimicrob Resist, 2019. 17: 112. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30553114/

Author Correspondence:

Prof. Dr. Semir A. Salim. Al Samarrai

Medical Director of Professor Al Samarrai Medical Center.

Dubai Healthcare City, Al-Razi Building 64, Block D, 2nd Floor, Suite 2018

E-mail: semiralsamarrai@hotmail.com

Tel: +97144233669