Prostate Cancer

Classification

Comprehensive Review Article

Part 2

Prof. Dr. Semir. A. Salim. Al Samarrai

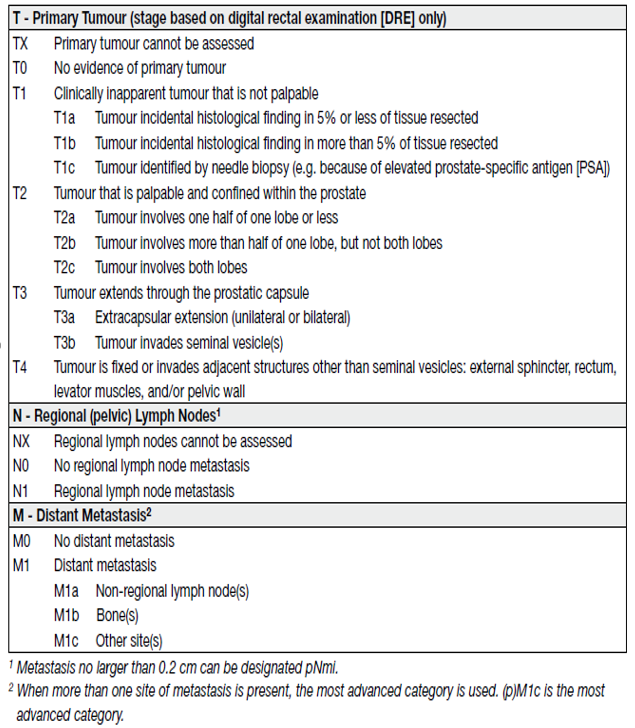

The objective of a tumour classification system is to combine patients with a similar clinical outcome. This allows for the design of clinical trials on relatively homogeneous patient populations, the comparison of clinical and pathological data obtained from different hospitals across the world, and the development of recommendations for the treatment of these patient populations. Throughout these Guidelines the 2017 Tumour, Node, Metastasis (TNM) classification for staging of PCa (Table 1) [1],

Table 1. Clinical Tumour Node Metastatis (TNM) classification of PCa

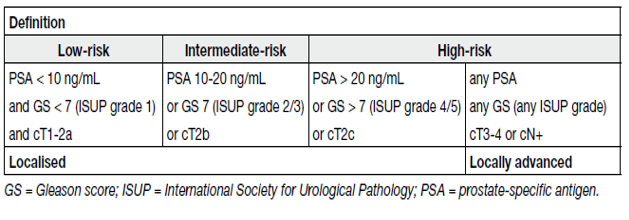

and the EAU risk group classification, which is essentially based on D’Amico’s classification system for PCa, are used (Table 2) [2].

Table 2. EAU risk groups for biochemical recurrence of localized and locally advanced prostate cancer

The latter classification is based on the grouping of patients with a similar risk of biochemical recurrence (BCR) after radical prostatectomy (RP) or external beam radiotherapy (EBRT). Magnetic resonance imaging and targeted biopsy may cause a stage shift in risk classification systems [3].

Clinical T stage only refers to digital rectal examination (DRE) findings; local imaging findings are not considered in the TNM classification. Pathological staging (pTNM) is based on histopathological tissue assessment and largely parallels the clinical TNM, except for clinical stage T1 and the T2 substages.

Pathological stages pT1a/b/c do not exist and histopathologically confirmed organ-confined PCas after RP arempathological stage pT2. The current Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) no longer recognises pT2 substages [1].

Of note: the EANM recently proposed a ‘miTNM’ (molecular imaging TNM) classification, taking into account prostate-specific membrane antigen positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PSMA PET/CT) findings [4]. The prognosis of the miT, miN and miM substages is likely to be better to their T, N and M counterparts due to the ‘Will Rogers phenomenon’; the extent of this prognosis shift remains to be assessed as well as its practical interest and impact [5].

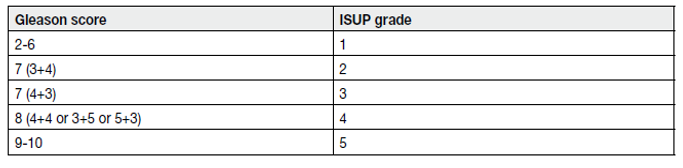

In the original Gleason grading system, 5 Gleason grades (ranging from 1–5) based on histological tumour architecture were distinguished, but in the 2005 and subsequent 2014 International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Gleason score (GS) modifications Gleason grades 1 and 2 were eliminated [6,7]. The 2005 ISUP modified GS of biopsy-detected PCa comprises the Gleason grade of the most extensive (primary) pattern, plus the second most common (secondary) pattern, if two are present. If one pattern is present, it needs to be doubled to yield the GS. For three grades, the biopsy GS comprises the most common grade plus the highest grade, irrespective of its extent. The grade of intraductal carcinoma should also be incorporated in the GS [8]. In addition to reporting of the carcinoma features for each biopsy, an overall (or global) GS based on the carcinoma-positive biopsies can be provided. The global GS takes into account the extent of each grade from all prostate biopsies. The 2014 ISUP endorsed grading system limits the number of PCa grades, ranging them from 1 to 5 (see Table 2 and table 3) [8,9].

Table 3. International Society of Urological Pathology 2014 grade (group) system

Further sub-stratification of the intermediate-risk group can be made and specifically the National Cancer Center Network (NCCN) Guidelines subdivide intermediate-risk disease into favourable intermediate-risk and unfavourable intermediate-risk, with unfavourable features including ISUP grade 3, and/or > 50% positive biopsy cores and/or at least two intermediate-risk factors [10].

The descriptor ‘clinically significant’ is widely used to differentiate PCa that may cause morbidity or death from types of PCa that do not. This distinction is particularly important as insignificant PCa that does not cause harm is so common [11]. Unless this distinction is made, such cancers are at high risk of being overtreated, with the treatment itself risking harmful side effects to patients. The over-treatment of insignificant PCas has been criticised as a major drawback of PSA testing [12].

However, defining what is clinically significant and what is insignificant PCa is difficult. In large studies of RP specimens which showed only ISUP grade 1 disease, extra prostatic extension (EPE) was extremely rare (0.28% of 2,502 cases) and seminal vesicle (SV) invasion or lymph node (LN) metastasis did not occur at all [13,14]. International Society for Urological Pathology grade 1 disease itself can therefore be considered clinically insignificant. Whilst ISUP grade 1 bears the hallmarks of cancer histologically, ISUP grade 1 itself does not behave in a clinically malignant fashion.

However, ISUP grade 1 is first diagnosed at biopsy and guides management decisions, not after the prostate has been removed. The current standard practice of MRI-targeted and template biopsies has reduced diagnostic inaccuracy [15], however sampling error may still occur such that higher grade cancer could be missed. This should be especially considered if the prior MRI showed a suspicious lesion, but only ISUP grade 1 was found at biopsy.

Another complexity in defining insignificant cancer is that ISUP grade 1 may progress to higher grades over time, becoming clinically significant at a later biopsy [16].

Therefore, although ISUP grade 1 itself can be described as clinically insignificant, it is important to take into account other factors, including imaging prior to biopsy and adequate sampling core number. When combined with low-risk clinical factors (see Table 2), ISUP grade 1 represents low-risk PCa, with its recommendation of preferred management being active surveillance (AS) or watchful waiting (WW).

It should be noted, therefore, that defining ISUP grade 1 as insignificant cancer does not mean it should be ignored, but safely observed.

Epidemiological and autopsy data also suggest that a proportion of ISUP grade 2 PCas would remain undetectable during a man’s life [17] and therefore may be overtreated. In current guidelines deferred treatment may be offered to select patients with intermediate-risk PCa [10], but evidence is lacking for appropriate selection criteria [18].

Recent papers have defined clinically significant cancer differently, commonly using ISUP grade 2 and above and even ISUP grade 3 and above, demonstrating the lack of consensus and evolution of its definition [19-22]. Some papers even provide more than one definition within a single study [23,24]. Although there is insufficient evidence to define clearly what clinically significant (cs) PCa is, it is imperative that authors define and state it in their own studies, including exactly how the disease was diagnosed.

A more precise stratification of the clinically heterogeneous subset of intermediate-risk group patients could provide a better framework for their management [25,26]. However, as yet, the best stratification and optimal treatment remain controversial.

REFERENCES:

1. Brierley, J.D., et al., TNM classification of malignant tumors. UICC International Union Against

Cancer. 8th edn. 2017.

https://www.uicc.org/resources/tnm-classification-malignant-tumours-8th-edition

2. Cooperberg, M.R., et al. The University of California, San Francisco Cancer of the Prostate Risk

Assessment score: a straightforward and reliable preoperative predictor of disease recurrence after

radical prostatectomy. J Urol, 2005. 173: 1938.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15879786/

3. Ploussard, G., et al. Decreased accuracy of the prostate cancer EAU risk group classification in the

era of imaging-guided diagnostic pathway: proposal for a new classification based on MRI-targeted

biopsies and early oncologic outcomes after surgery. World J Urol, 2020. 38: 2493.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31838560/

4. Ceci, F., et al. E-PSMA: the EANM standardized reporting guidelines v1.0 for PSMA-PET. Eur J Nucl

Med Mol Imaging, 2021. 48: 1626.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33604691/

5. van den Bergh, R.C.N., et al. Re: Andrew Vickers, Sigrid V. Carlsson, Matthew Cooperberg. Routine

Use of Magnetic Resonance Imaging for Early Detection of Prostate Cancer Is Not Justified by the

Clinical Trial Evidence. Eur Urol 2020;78:304-6: Prebiopsy MRI: Through the Looking Glass. Eur

Urol, 2020. 78: 310.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32660749/

6. Epstein, J.I., et al. The 2005 International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Consensus

Conference on Gleason Grading of Prostatic Carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol, 2005. 29: 1228.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16096414/

7. Epstein, J.I., et al. The 2014 International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Consensus

Conference on Gleason Grading of Prostatic Carcinoma: Definition of Grading Patterns and

Proposal for a New Grading System. Am J Surg Pathol, 2016. 40: 244.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26492179/

8. van Leenders, G., et al. The 2019 International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Consensus

Conference on Grading of Prostatic Carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol, 2020. 44: e87.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32459716/

9. Epstein, J.I., et al. A Contemporary Prostate Cancer Grading System: A Validated Alternative to the

Gleason Score. Eur Urol, 2016. 69: 428.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26166626/

10. Preisser, F., et al. Intermediate-risk Prostate Cancer: Stratification and Management. Eur Urol Oncol,

2020. 3: 270.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32303478/

11. Bell, K.J., et al. Prevalence of incidental prostate cancer: A systematic review of autopsy studies. Int

J Cancer, 2015. 137: 1749.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25821151/

12. Moyer, V.A. Screening for prostate cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation

statement. Ann Intern Med, 2012. 157: 120.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22801674/

13. Anderson, B.B., et al. Extraprostatic Extension Is Extremely Rare for Contemporary Gleason Score 6

Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol, 2017. 72: 455.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27986368/

14. Ross, H.M., et al. Do adenocarcinomas of the prostate with Gleason score (GS) <6 have the

potential to metastasize to lymph nodes? Am J Surg Pathol, 2012. 36: 1346.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22531173/

15. Goel, S., et al. Concordance Between Biopsy and Radical Prostatectomy Pathology in the Era of

Targeted Biopsy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Eur Urol Oncol, 2020. 3: 10.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31492650/

16. Inoue, L.Y., et al. Modeling grade progression in an active surveillance study. Stat Med, 2014.

33: 930.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24123208/

17. Van der Kwast, T.H., et al. Defining the threshold for significant versus insignificant prostate cancer.

Nat Rev Urol, 2013. 10: 473.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23712205/

18. Overland, M.R., et al. Active surveillance for intermediate-risk prostate cancer: yes, but for whom?

Curr Opin Urol, 2019. 29: 605.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31436567/

19. Kasivisvanathan, V., et al. MRI-Targeted or Standard Biopsy for Prostate-Cancer Diagnosis. N Engl

J Med, 2018. 378: 1767.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29552975/

20. Rouviere, O., et al. Use of prostate systematic and targeted biopsy on the basis of multiparametric

MRI in biopsy-naive patients (MRI-FIRST): a prospective, multicentre, paired diagnostic study.

Lancet Oncol, 2019. 20: 100.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30470502/

21. van der Leest, M., et al. Head-to-head Comparison of Transrectal Ultrasound-guided Prostate

Biopsy Versus Multiparametric Prostate Resonance Imaging with Subsequent Magnetic Resonanceguided

Biopsy in Biopsy-naive Men with Elevated Prostate-specific Antigen: A Large Prospective

Multicenter Clinical Study. Eur Urol, 2019. 75: 570.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30477981/

22. Emmett, L., et al. The Additive Diagnostic Value of Prostate-specific Membrane Antigen Positron

Emission Tomography Computed Tomography to Multiparametric Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Triage in the Diagnosis of Prostate Cancer (PRIMARY): A Prospective Multicentre Study. Eur Urol,

2021. 80: 682.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34465492/

23. Ahmed, H.U., et al. Diagnostic accuracy of multi-parametric MRI and TRUS biopsy in prostate

cancer (PROMIS): a paired validating confirmatory study. Lancet, 2017. 389: 815.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28110982/

24. Thompson, J.E., et al. Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging guided diagnostic biopsy

detects significant prostate cancer and could reduce unnecessary biopsies and over detection: a

prospective study. J Urol, 2014. 192: 67.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24518762/

25. Kane, C.J., et al. Variability in Outcomes for Patients with Intermediate-risk Prostate Cancer

(Gleason Score 7, International Society of Urological Pathology Gleason Group 2-3) and

Implications for Risk Stratification: A Systematic Review. Eur Urol Focus, 2017. 3: 487.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28753804/

26. Zumsteg, Z.S., et al. Unification of favourable intermediate-, unfavourable intermediate-, and very

high-risk stratification criteria for prostate cancer. BJU Int, 2017. 120: E87.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28464446/

Author Correspondence:

Prof. Dr. Semir A. Salim. Al Samarrai

Medical Director of Professor Al Samarrai Medical Center.

Dubai Healthcare City, Al-Razi Building 64, Block D, 2nd Floor, Suite 2018

E-mail: semiralsamarrai@hotmail.com

Tel: +97144233669