Prostate Cancer

Hormonal therapy

Comprehensive Review Article

Part 6

Prof. Dr. Semir. A. Salim. Al Samarrai

Hormonal therapy:

- Different types of hormonal therapy

The hormonal therapy is the fourth modality of PCA treatment, there are different types of hormonal therapy.

Androgen deprivation can be achieved by suppressing the secretion of testicular androgens in different ways.

This can be combined with inhibiting the action of circulating androgens at the level of their receptor which has been known as complete (or maximal or total) androgen blockade (CAB) using the old-fashioned antiandrogens [1].

Testosterone-lowering therapy (castration):

- Castration level

The testosterone-lowering therapy (castration) aims to decrease the testosterone level to castration level, which means the castration level of testosterone is < 50 ng/dL (1.7 nmol/L), which was defined more than 40 years ago when testosterone testing was less sensitive. Current methods have shown that the mean value after surgical castration is 15 ng/dL [2]. Therefore, a more appropriate level should be defined as < 20 ng/dL (1 nmol/L).

- Bilateral orchiectomy

The castration modality with Bilateral orchiectomy or subcapsular pulpectomy is still considered the primary treatment modality for ADT. It is a simple, cheap and virtually complication-free surgical procedure. It is easily performed under local anaesthesia, and it is the quickest way to achieve a castration level which is usually reached within less than twelve hours. It is irreversible and therefore does not allow for intermittent treatment [3].

- Oestrogens

One of the hormonal therapy modality is the treatment with oestrogens results in testosterone suppression and is not associated with bone loss [4].

Early studies tested oral diethylstilboestrol (DES) at several doses. Due to severe side effects, especially thromboembolic complications, even at lower doses these drugs are not considered as standard first-line treatment [5–7].

- Luteinising-hormone-releasing hormone agonists

Long-acting LHRH agonists are currently the main forms of ADT. These synthetic analogues of LHRH are delivered as depot injections on a 1-, 2-, 3-, 6-monthly, or yearly, basis. The first injection induces a transient rise in luteinising hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) leading to the ‘testosterone surge’ or ‘flare-up’ phenomenon which starts two to three days after administration and lasts for about one week.

This may lead to detrimental clinical effects (the clinical flare) such as increased bone pain, acute bladder outlet obstruction, obstructive renal failure, spinal cord compression, and cardiovascular death due to hypercoagulation status [8].

- Luteinising-hormone-releasing hormone antagonists

Luteinising-hormone-releasing hormone antagonists immediately bind to LHRH receptors, leading to a rapid decrease in LH, FSH and testosterone levels without any flare. The practical shortcoming of these compounds is the lack of a long-acting depot formulation with, so far, only monthly formulations being available. Degarelix is a LHRH antagonist. The standard dosage is 240 mg in the first month followed by monthly injections of 80 mg. Most patients achieve a castrate level at day three [9].

Relugolix is an oral gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist. It was compared to the LHRH agonist leuprolid in a randomised phase III trial [10]. The primary endpoint was sustained testosterone suppression to castrate levels through 48 weeks. There was a significant difference of 7.9 percentage points (95% CI: 4.1–11.8) showing non-inferiority and superiority of relugolix. The incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events was significantly lower with relugolix (prespecified safety analysis). Relugolix has been approved by the FDA [11].

- The anti-androgens

The anti-androgens are oral compounds and classified according to their chemical structure as:

• steroidal, e.g., cyproterone acetate (CPA), megestrol acetate and medroxyprogesterone acetate;

• non-steroidal or pure, e.g., nilutamide, flutamide and bicalutamide.

Both classes compete with androgens at the receptor level. This leads to an unchanged or slightly elevated testosterone level. Conversely, steroidal anti-androgens have progestational properties leading to central inhibition by crossing the blood-brain barrier.

- The steroidal anti-androgens

These compounds are synthetic derivatives of hydroxyprogesterone. Their main pharmacological side effects are secondary to castration (gynaecomastia is quite rare) whilst the non-pharmacological side effects are cardiovascular toxicity (4–40% for CPA) and hepatotoxicity.

- Non-steroidal anti-androgens

Non-steroidal anti-androgen monotherapy with e.g., nilutamide, flutamide or bicalutamide does not suppress testosterone secretion and it is claimed that libido, overall physical performance and bone mineral density (BMD) are frequently preserved [12]. Non-androgen-related pharmacological side effects differ between agents. Bicalutamide shows a more favourable safety and tolerability profile than flutamide and nilutamide [800]. The dosage licensed for use in CAB is 50 mg/day, and 150 mg for monotherapy. The androgen pharmacological side effects are mainly gynaecomastia (70%) and breast pain (68%). However, non-steroidal anti-androgen monotherapy offers clear bone protection compared with LHRH analogues and probably LHRH antagonists [12,13]. All three agents share the potential for liver toxicity (occasionally fatal), requiring regular monitoring of patients’ liver enzymes.

- New androgen pathway targeting agents (ARTA)

Once on ADT the development of castration-resistance (CRPC) is only a matter of time. It is considered to be mediated through two main overlapping mechanisms: androgen-receptor (AR)-independent and AR-dependent mechanisms. In CRPC, the intracellular androgen level is increased compared to androgen sensitive cells and an over-expression of the AR has been observed, suggesting an adaptive mechanism [14].

This has led to the development of several new compounds targeting the androgen axis. In mCRPC, AAP and enzalutamide have been approved. In addition to ADT (sustained castration), AAP, apalutamide and enzalutamide have been approved for the treatment of metastatic hormone sensitive Pca (mHSPC) by the FDA and the EMA. For the updated approval status see EMA and FDA websites [15–19].

Finally, apalutamide, darolutamide and enzalutamide have been approved for non-metastatic CRPC (nmCRPC) at high risk of further metastases [20–24].

- Abiraterone acetate

Abiraterone acetate is a CYP17 inhibitor (a combination of 17α-hydrolase and 17,20-lyase inhibition). By blocking CYP17, abiraterone acetate significantly decreases the intracellular testosterone level by suppressing its synthesis at the adrenal level and inside the cancer cells (intracrine mechanism). This compound must be used together with prednisone/prednisolone to prevent drug-induced hyperaldosteronism [15,18].

- Apalutamide, darolutamide, enzalutamide (alphabetical order)

These agents are novel non-steroidal anti-androgens with a higher affinity for the AR receptor than bicalutamide. While previous non-steroidal anti-androgens still allow transfer of ARs to the nucleus and would act as partial agonists, all three agents also block AR transfer and therefore suppress any possible agonist-like activity [19–21]. Darolutamide has structurally unique properties [20]. In particular, in preclinical studies, it showed not to cross the blood-brain barrier [25,26].

New compounds:

- PARP inhibitors

Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors (PARPi) block the enzyme poly ADP ribose polymerase (PARP) and were developed aiming to selectively target cancer cells harbouring BRCA mutations and other mutations inducing homologous recombination deficiency and high level of replication pressure with a sensitivity to PARPi treatment.

- Immune checkpoint inhibitors

The immune checkpoints are key regulators of the immune system. Checkpoint proteins, such as B7-1/B7-2 on antigen-presenting cells (APC) and CTLA-4 on T cells, help keep the immune responses in an equilibrium.

Approved checkpoint inhibitors target the molecules CTLA4, programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), and programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1). Programmed death-ligand 1 is the transmembrane programmed cell death 1 protein which interacts with PD-L1 (PD-1 ligand 1).

Examples of PD-1 inhibitors are pembrolizumab and nivolumab; of PD-L1 inhibitors, atezolizumab, avelumab and durvalumab and an example of CTLA4 inhibitors is ipilimumab [27,28].

- Protein kinase B (AKT) inhibitors

Protein kinase B (AKT) inhibitors are small molecules which are designed to target and bind to all three isoforms of AKT. Aberrant activation of the PI3K (phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase)/AKT pathway, predominately due to PTEN loss (phosphatase and tensin homologue deleted from chromosome 10), is common in Pca (40–60% of mCRPC) and is associated with worse prognosis. The androgen receptor signalling and AKT pathway are reciprocally cross-regulated, so that inhibition of one leads to upregulation of the other.

- Radiopharmaceutical therapy

Radiopharmaceutical therapy (RPT) is based on the delivery of radioactive atoms to tumour-associated targets.

The mechanism of action for RPT is radiation-induced killing of cells. Radionuclides with different emission properties are used to deliver radiation.

- Investigational therapies

The investigational therapies are modalities options, which have besides RP, EBRT and brachytherapy emerged as potential therapeutic options in patients with clinically localised PCa [29–32]. Both whole gland- and focal treatment will be considered, looking particularly at high-intensity focused US (HIFU), cryotherapeutic ablation of the prostate (cryotherapy) and focal photodynamic therapy.

- Cryotherapy

Cryotherapy uses freezing techniques to induce cell death by dehydration resulting in protein denaturation, direct rupture of cellular membranes by ice crystals and vascular stasis and microthrombi, resulting in stagnation of the microcirculation with consecutive ischaemic apoptosis [29–32].

- High-intensity focused ultrasound

The High-intensity focused US consists of focused US waves emitted from a transducer that cause tissue damage by mechanical and thermal effects as well as by cavitation [33]. The goal of HIFU is to heat malignant tissue above 65°C so that it is destroyed by coagulative necrosis. High-intensity focused US is performed under general or spinal anaesthesia, with the patient lying in the lateral or supine position. High-intensity focused US has previously been widely used for whole-gland therapy. The major adverse effects of HIFU include acute urinary retention (10%), ED (23%), urethral stricture (8%), rectal pain or bleeding (11%), recto-urethral fistula (0–5%) and urinary incontinence (10%) [34]. Disadvantages of HIFU include difficulty in achieving complete ablation of the prostate, especially in glands larger than 40 mL, and in targeting cancers in the anterior zone of the prostate.

- Focal therapy

Most focal therapies to date have been achieved with ablative technologies: cryotherapy, HIFU, photodynamic therapy, electroporation, and focal RT by brachytherapy or CyberKnifeR Robotic Radiosurgery System technology (Accuray Inc., Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The main purpose of focal therapy is to ablate tumours selectively whilst limiting toxicity by sparing the neurovascular bundles, sphincter and urethra [35–37].

Treatment by disease stages:

- Treatment of low-risk disease

The treatment of prostate cancer by disease stage includes treatment of low-risk disease. The active surveillance (AC) should be considered for all such patients because the main risk for these men is over treatment.

- Active surveillance – inclusion criteria

Guidance regarding selection criteria for active surveillance (AS) is limited by the lack of data from prospective RCTs. As a consequence, the Panel undertook an international collaborative study involving healthcare practitioners and patients to develop consensus statements for deferred treatment with curative intent for localised PCa, covering all domains of AS (DETECTIVE Study) [38], as well as a formal systematic review on the various AS protocols [39]. The criteria most often published include: ISUP grade 1, clinical stage cT1c or cT2a, PSA < 10 ng/mL and PSA-D < 0.15 ng/mL/cc [40,41]. The latter threshold remains controversial [41,42].

- The treatment of intermediate-risk disease

When managed with non-curative intent, intermediate-risk PCa is associated with 10-year and 15-year PCSM rates of 13.0% and 19.6%, respectively [43]. These estimates are based on systematic biopsies and may be overestimated in the era of MRI-targeted biopsies.

Consequently, active surveillance (AS) can be cautiously considered in patients with low-volume ISUP 2 (defined as < 3 positive cores and cancer involvement < 50% core involvement CI/per core) or another single element of intermediate-risk disease (i.e. favourable intermediate-risk disease) except ISUP 3 disease, which should be excluded.

- Radical prostatectomy

The radical prostatectomy by patients with intermediate-risk PCa should be informed about the results of two RCTs (SPCG-4 and PIVOT) comparing RRP vs. WW in localised PCa. An eLND should be performed in intermediate-risk Pca if the estimated risk for pN+ exceeds 5% [44] or 7% if using the nomogram by Gandaglia et al., which incorporates MRI-guided biopsies [45]. In all other cases eLND can be omitted, which means accepting a low risk of missing positive nodes.

Radiation therapy:

- Recommended IMRT/VMAT for intermediate-risk Pca

The radiation therapy IMRT/VMAT is recommended for intermediate-risk PCa. Patients suitable for ADT can be given combined IMRT/VMAT with short-term ADT (4–6 months) [46–48]. For patients unsuitable (e.g., due to co-morbidities) or unwilling to accept ADT (e.g. to preserve their sexual health) the recommended treatment is IMRT/VMAT (76–78 Gy) or a combination of IMRT/VMAT and brachytherapy as described below.

- Brachytherapy for intermediate-risk Pca

The authors of a systematic review of LDR brachytherapy recommend that LDR brachytherapy monotherapy can be offered to patients with NCCN favourable intermediate-risk disease and good urinary function [49].

- The treatment of high risk localized disease

Patients with high-risk PCa are at an increased risk of PSA failure, need for secondary therapy, metastatic progression and death from PCa.

- Radical prostatectomy

Radical prostatectomy is provided when the tumour is not fixed to the pelvic wall or there is no invasion of the urethral sphincter, RP is a reasonable option in selected patients with a low tumour volume. Extended PLND should be performed in all high-risk PCa cases [44,50].

- ISUP grade 4–5

The incidence of organ-confined disease is 26–31% in men with an ISUP grade > 4 on systematic biopsy. Several retrospective case series have demonstrated CSS rates over 60% at 15 years after RP in the context of a multi-modal approach (adjuvant or salvage ADT and/or RT) in patients with a biopsy ISUP grade 5 [51,52,53,54].

- Prostate-specific antigen > 20 ng/mL

Reports in patients with a PSA > 20 ng/mL who underwent surgery as initial therapy within a multi-modal approach demonstrated a CSS at 15 years of over 70% [51,52,55,56–58].

At 15 years follow-up cN0 patients who undergo RP but who were found to have pN1 were reported to havean overall CSS and OS of 45% and 42%, respectively [59-65].

- External beam radiation therapy

For high-risk localised PCa, a combined modality approach should be used consisting of IMRT/VMAT plus long-term ADT.

- Brachytherapy boost

In men with intermediate- or high-risk PCa, brachytherapy boost with supplemental EBRT and hormonal treatment may be considered.

- Treatment of locally advanced Pca

The treatment of locally advanced PCa in the absence of high-level evidence, a recent systematic review could not define the most optimal treatment option [66]. Randomised controlled trials are only available for EBRT. A local treatment combined with a systemic treatment provides the best outcome, provided the patient is ready and fit enough to receive both.

- Radical prostatectomy

Radical prostatectomy for locally advanced disease as part of a multi-modal therapy has been reported [67,68,69].

However, the comparative oncological effectiveness of RP as part of a multi-modal treatment strategy vs. upfront EBRT with ADT for locally advanced PCa remains unknown, although a prospective phase III RCT (SPCG-15) comparing RP (with or without adjuvant or salvage EBRT) against primary EBRT and ADT among patients with locally advanced (T3) disease is currently recruiting [70].

- Radiotherapy for locally advanced Pca

In locally advanced disease RCTs have clearly established that the additional use of long-term ADT combined with RT produces better OS than ADT or Radiotherapy (RT) alone [66].

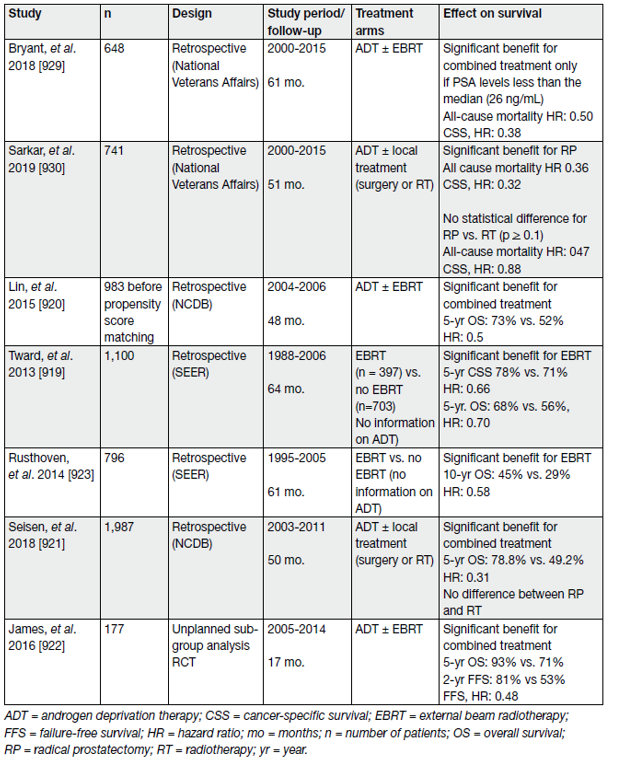

The management of cN1M0 PCa is mainly based on long-term ADT combined with a local treatment. The benefit of adding local treatment has been assessed in various retrospective studies, summarised in one systematic review [71] including 5 studies only [72–76]. The findings suggested an advantage in both OS and CSS after local treatment (RT or RP) combined with ADT as compared to ADT alone. (table 1)

Table 1. Selected studies assessing local treatment in (any cT) cN1 M0 prostate cancer patients

- Adjuvant treatment after radical prostatectomy

The adjuvant treatment after radical prostatectomy is by definition additional to the primary or initial therapy with the aim of decreasing the risk of relapse. A post-operative detectable PSA is an indication of persistent prostate. All information listed below refers to patients with a post-operative undetectable PSA.

- Risk factors for relapse

Patients with ISUP grade > 2 in combination with EPE (pT3a) and particularly those with SV invasion (pT3b) and/or positive surgical margins are at high risk of progression, which can be as high as 50% after 5 years [77]. Irrespective of the pT stage, the number of removed nodes [78–85], tumour volume within the LNs and capsular perforation of the nodal metastases are predictors of early recurrence after RP for pN1 disease [86].

A LN density (defined as ‘the percentage of positive LNs in relation to the total number of analysed/removed LNs’) of over 20% was found to be associated with poor prognosis [87]. The number of involved nodes seems to be a major factor for predicting relapse [80,81,88]; the threshold considered is less than 3 positive nodes from an ePLND [89,80,88]. However, prospective data are needed before defining a definitive threshold value.

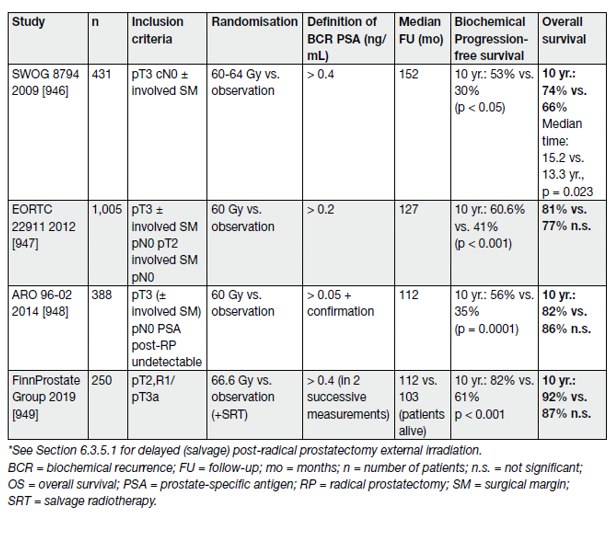

Four prospective RCTs have assessed the role of immediate post-operative RT (adjuvant RT [ART]), demonstrating an advantage (endpoint, development of BCR) in high-risk patients (e.g., pT2/pT3 with positive surgical margins and GS 8–10) post-RP (Table 2).

Table 2. Overview of all four randomised trials for adjuvant surgical bed radiation therapy after RP

- Persistent PSA after radical prostatectomy

Between 5 and 20% of men continue to have detectable is associated with more advanced disease (such as positive surgical margins, pathologic stage > T3a, positive nodal status and/or pathologic ISUP grade > 3) and poor prognosis. Initially defined as > 0.1 ng/mL, improvements in the sensitivity of PSA assays now allow for the detection of PSA at much lower levels.

- Management of PSA-only recurrence after treatment with curative intent

The management of PSA-only recurrence after treatment with curative intent is to establish when PSA rise clinically.

Between 27% and 53% of all patients undergoing RP or RT develop a rising PSA (PSA recurrence). Whilst a rising PSA level universally precedes metastatic progression, physicians must inform the patient that the natural history of PSA-only recurrence may be prolonged and that a measurable PSA may not necessarily lead to clinically apparent metastatic disease. Physicians treating patients with PSA-only recurrence face a difficult set of decisions in attempting to delay the onset of metastatic disease and death while avoiding overtreating patients whose disease may never affect their OS or QoL. It should be emphasised that the treatment recommendations for these patients should be given after discussion in a multidisciplinary team.

- Controversies in the definitions of clinically relevant PSA relapse

After RP, the threshold that best predicts further metastases is a PSA > 0.4 ng/mL and rising [90–92]. However, with access to ultra-sensitive PSA testing, a rising PSA much below this level will be a cause for concern for patients.

After HIFU or cryotherapy no endpoints have been validated against clinical progression or survival; therefore, it is not possible to give a firm recommendation of an acceptable PSA threshold after these alternative local treatments [93].

- Natural history of biochemical recurrence

Once a PSA recurrence has been diagnosed, it is important to determine whether the recurrence has developed at local or distant sites.

After primary RP its impact ranges from HR 1.03 (95% CI: 1.004–1.06) to HR 2.32 (95% CI: 1.45–3.71) [94,95]. After primary RT, OS rates are approximately 20% lower at 8 to 10 years follow-up even in men with minimal co-morbidity [96,97].

The risk of subsequent metastases, PCa-specific- and overall mortality may be predicted by the initial clinical and pathologic factors (e.g., T-category, PSA, ISUP grade) and PSA kinetics (PSA-DT and interval to PSA failure), which was further investigated by the systematic review [93].

For patients with BCR after RP, the following outcomes were found to be associated with significant prognostic factors:

• Distant metastatic recurrence: positive surgical margins, high RP specimen pathological ISUP grade, high pT category, short PSA-DT, high pre-SRT PSA;

• Prostate-cancer-specific mortality: high RP specimen pathological ISUP grade, short interval to biochemical failure as defined by investigators, short PSA-DT;

• Overall mortality: high RP specimen pathological ISUP grade, short interval to biochemical failure, high PSA-DT.

For patients with BCR after RT, the corresponding outcomes are:

• Distant metastatic recurrence: high biopsy ISUP grade, high cT category, short interval to biochemical failure;

• Prostate-cancer-specific mortality: short interval to biochemical failure;

• Overall mortality: high age, high biopsy ISUP grade, short interval to biochemical failure, high initial (pretreatment)

PSA.

- The role of imaging in PSA-only reccurence

Imaging is only of value if it leads to a treatment change which results in an improved outcome. In practice, however, there are very limited data available regarding the outcomes consequent on imaging at recurrence.

- Assessment of metastases

Because BCR after RP or RT precedes clinical metastases by 7 to 8 years on average [82,98], the diagnostic yield of common imaging techniques (bone scan and abdominopelvic CT) is low in asymptomatic patients [99].

- Choline PET/CT

In two different meta-analyses the combined sensitivities and specificities of choline PET/CT for all sites of recurrence in patients with BCR were 86–89% and 89–93%, respectively [100,101].

Choline PET/CT may detect multiple bone metastases in patients showing a single metastasis on bone scan [102] and may be positive for bone metastases in up to 15% of patients with BCR after RP and negative bone scan [103].

In patients with BCR after RP, PET/CT detection rates are only 5–24% when the PSA level is < 1 ng/mL but rises to 67–100% when the PSA level is > 5 ng/mL.

Despite its limitations, choline PET/CT may change medical management in 18–48% of patients with BCR after primary treatment [104-106]. Choline PET/CT should only be recommended in patients fit enough for curative loco-regional salvage treatment.

- 18F-Fluciclovine PET and PET/CT

18F-Fluciclovine PET/CT has been approved in the U.S. and Europe and it is therefore one of the PCa-specific radiotracers widely commercially available [107-109].

18F-Fluciclovine PET/CT has a slightly higher sensitivity than choline PET/CT in detecting the site of relapse in BCR [110].

- Prostate-specific membrane antigen based PET/CT

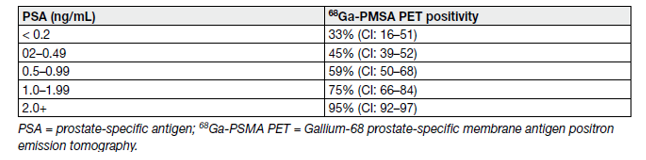

Prostate-specific membrane antigen PET/CT has shown good potential in patients with BCR, although most studies are limited by their retrospective design. Reported predictors of 68Ga-PSMA PET in the recurrence setting were recently updated based on a high-volume series (see Table 3) [111]. High sensitivity (75%) and specificity (99%) were observed on per-lesion analysis.

Table 3. PSMA-positivity separated by PSA level category [982]

Prostate-specific membrane antigen PET/CT seems substantially more sensitive than choline PET/CT, especially for PSA levels < 1 ng/mL [112,113].

- Whole-body and axial MRI

Whole body MRI has not been widely evaluated in BCR because of its limited value in the detection of early metastatic involvement in normal-sized LNs [114,115]. In a prospective series of 68 patients with BCR, the diagnostic performance of DW-MRI was significantly lower than that of 68Ga-PSMA PET/CT and 18NaF PET/CT for diagnosing bone metastases [116].

Assessment of local recurrences:

- Local recurrence after radical prostatectomy

Because the sensitivity of anastomotic biopsies is low, especially for PSA levels < 1 ng/mL [99], salvage RT is usually decided on the basis of BCR without histological proof of local recurrence. The dose delivered to the prostatic fossa tends to be uniform since it has not been demonstrated that a focal dose escalation at the site of recurrence improves the outcome. Therefore, most patients undergo salvage RT without local imaging.

The detection rates of 68Ga-PSMA PET/CT in patients with BCR after RP increase with the PSA level [117]. Prostate-specific membrane antigen PET/CT studies showed that a substantial part of recurrences after RP were located outside the prostatic fossa even at low PSA levels [118,119]. Combining 68Ga-PSMA PET and MRI may improve the detection of local recurrences, as compared to 68Ga-PSMA PET/CT [120-122].

- Local recurrence after radiation therapy

In patients with BCR after RT, biopsy status is a major predictor of outcome, provided the biopsies are obtained 18–24 months after initial treatment. Given the morbidity of local salvage options it is necessary to obtain histological proof of the local recurrence before treating the patient [99].

Transrectal US is not reliable in identifying local recurrence after RT. In contrast, MRI has yielded excellent results and can be used for biopsy targeting and guiding local salvage treatment [99,123-126], even if it slightly underestimates the volume of the local recurrence [127].

- Treatment of PSA-only recurrences after radical prostatectomy

Salvage radiotherapy for PSA-only recurrence after radical prostatectomy (cTxcNOMO, Without PET/CT).

Early SRT provides the possibility of cure for patients with an increasing PSA after RP.

The PSA level at BCR was shown to be prognostic [1028]. More than 60% of patients who are treated before the PSA level rises to > 0.5 ng/mL will achieve an undetectable PSA level [129-132], corresponding to a ~80% chance of being progression-free 5 years later [133].

The EAU BCR definitions have been externally validated and may be helpful for individualised treatment decisions [134]. Despite the indication for salvage RT, a ‘wait and see‘ strategy remains an option for the EAU BCR ‘Low-Risk’ group [93,135]. For an overview see Table 4 and 5.

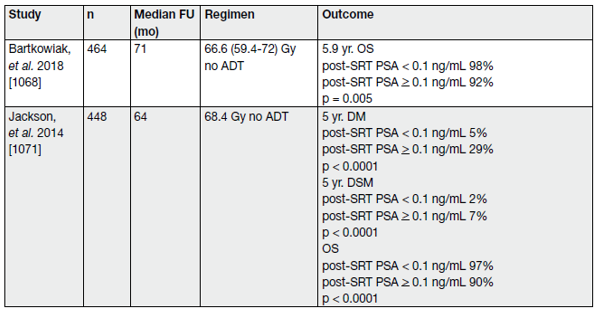

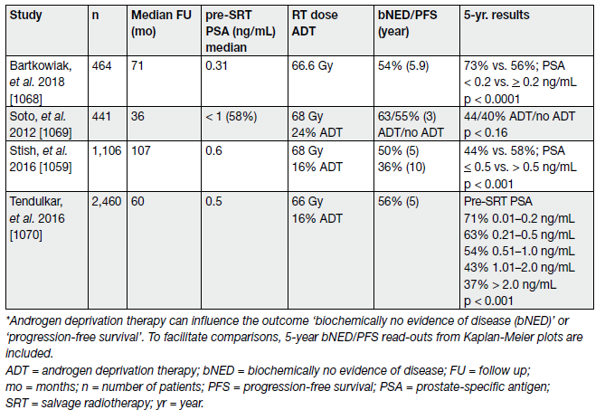

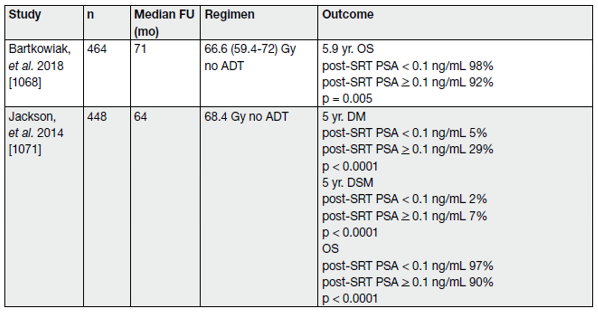

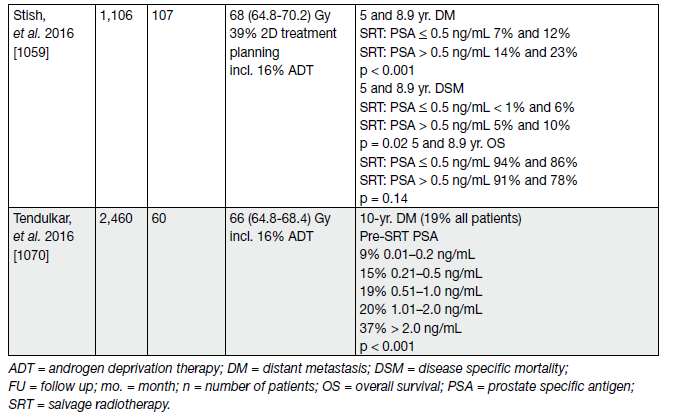

Table 4. Selected studies of post-prostatectomy salvage radiotherapy, stratified by pre-salvage radiotherapy PSA level* (cTxcN0M0, without PET/CT)

Table 5. Recent studies reporting clinical endpoints after SRT (cTxcN0M0, without PET/CT) (the majority of included patients did not receive ADT)

Although biochemical progression is now widely accepted as a surrogate marker of PCa recurrence; metastatic disease, disease-specific and OS are more meaningful endpoints to support clinical decision-making. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the impact of BCR after RP reports salvage radiotherapy (SRT) to be favourable for OS and PCa-specific mortality.

REFERENCES:

1. Pagliarulo, V., et al. Contemporary role of androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. Eur Urol, 2012. 61: 11. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21871711/

2. Oefelein, M.G., et al. Reassessment of the definition of castrate levels of testosterone: implications for clinical decision making. Urology, 2000. 56: 1021. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11113751/

3. Desmond, A.D., et al. Subcapsular orchiectomy under local anaesthesia. Technique, results and implications. Br J Urol, 1988. 61: 143. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3349279/

4. Scherr, D.S., et al. The nonsteroidal effects of diethylstilbestrol: the rationale for androgen deprivation therapy without estrogen deprivation in the treatment of prostate cancer. J Urol, 2003. 170: 1703. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14532759/

5. Klotz, L., et al. A phase 1-2 trial of diethylstilbestrol plus low dose warfarin in advanced prostate carcinoma. J Urol, 1999. 161: 169. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10037391/

6. Farrugia, D., et al. Stilboestrol plus adrenal suppression as salvage treatment for patients failing treatment with luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone analogues and orchidectomy. BJU Int, 2000. 85: 1069. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10848697/

7. Hedlund, P.O., et al. Parenteral estrogen versus combined androgen deprivation in the treatment of metastatic prostatic cancer: part 2. Final evaluation of the Scandinavian Prostatic Cancer Group (SPCG) Study No. 5. Scand J Urol Nephrol, 2008. 42: 220. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18432528/

8. Bubley, G.J. Is the flare phenomenon clinically significant? Urology, 2001. 58: 5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11502435/

9. Klotz, L., et al. The efficacy and safety of degarelix: a 12-month, comparative, randomized, openlabel, parallel-group phase III study in patients with prostate cancer. BJU Int, 2008. 102: 1531. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19035858/

10. Shore, N.D., et al. Oral Relugolix for Androgen-Deprivation Therapy in Advanced Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med, 2020. 382: 2187. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32469183/

11. U.S. Food & Drug Adminstration. FDA approves relugolix for advanced prostate cancer. 2020. [Access date March 2022]. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-relugolixadvanced-prostate-cancer

12. Smith, M.R., et al. Bicalutamide monotherapy versus leuprolide monotherapy for prostate cancer: effects on bone mineral density and body composition. J Clin Oncol, 2004. 22: 2546. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15226323/

13. Wadhwa, V.K., et al. Long-term changes in bone mineral density and predicted fracture risk in patients receiving androgen-deprivation therapy for prostate cancer, with stratification of treatment based on presenting values. BJU Int, 2009. 104: 800. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19338564/

14. Montgomery, R.B., et al. Maintenance of intratumoral androgens in metastatic prostate cancer: a mechanism for castration-resistant tumor growth. Cancer Res, 2008. 68: 4447. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18519708/

15. U.S. Food & Drug Adminstration. FDA approves abiraterone acetate in combination with prednisone for high-risk metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer. 2018. [Access date March 2022]. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-abirateroneacetate-combination-prednisone-high-risk-metastatic-castration-sensitive

16. U.S. Food & Drug Adminstration. FDA approves enzalutamide for metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer. 2019. [Access date March 2022]. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-enzalutamidemetastatic-castration-sensitive-prostate-cancer

17. U.S. Food & Drug Adminstration. FDA approves apalutamide for metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer. 2019. [Access date March 2022]. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-apalutamidemetastatic-castration-sensitive-prostate-cancer

18. European Medicines Agency. Zytiga. 2011. [Access date March 2022]. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/zytiga

19. European Medicines Agency. Erleada (apalutamide). 2019. [Access date March 2022]. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/erleada

20. European Medicines Agency. Nubeqa (darolutamide). 2020. [Access date March 2022]. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/nubeqa

21. European Medicines Agency. Xtandi (enzalutamide). 2013. [Access date March 2022]. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/xtandi

22. Chi, K.N., et al. Apalutamide for Metastatic, Castration-Sensitive Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med, 2019. 381: 13. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31150574/

23. Armstrong, A.J., et al. ARCHES: A Randomized, Phase III Study of Androgen Deprivation Therapy With Enzalutamide or Placebo in Men With Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer. J Clin Oncol, 2019. 37: 2974. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31329516/

24. Fizazi, K., et al. Abiraterone plus Prednisone in Metastatic, Castration-Sensitive Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med, 2017. 377: 352. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28578607/

25. Moilanen, A.M., et al. Discovery of ODM-201, a new-generation androgen receptor inhibitor targeting resistance mechanisms to androgen signaling-directed prostate cancer therapies. Sci Rep, 2015. 5: 12007. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26137992/

26. Zurth, C., et al. Blood-brain barrier penetration of [14C]darolutamide compared with [14C] enzalutamide in rats using whole body autoradiography. J Clin Oncol, 2018. 36: 345. https://ascopubs.org/doi/abs/10.1200/JCO.2018.36.6_suppl.345#

27. Darvin, P., et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors: recent progress and potential biomarkers. Exp Molecular Med, 2018. 50: 1. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30546008/

28. Hargadon, K.M., et al. Immune checkpoint blockade therapy for cancer: An overview of FDAapproved immune checkpoint inhibitors. Int Immunopharmacol, 2018. 62: 29. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29990692/

29. Fahmy, W.E., et al. Cryosurgery for prostate cancer. Arch Androl, 2003. 49: 397. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12893518/

30. Rees, J., et al. Cryosurgery for prostate cancer. BJU Int, 2004. 93: 710. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15049977/

31. Han, K.R., et al. Third-generation cryosurgery for primary and recurrent prostate cancer. BJU Int, 2004. 93: 14. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14678360/

32. Beerlage, H.P., et al. Current status of minimally invasive treatment options for localized prostate carcinoma. Eur Urol, 2000. 37: 2. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10671777/

33. Madersbacher, S., et al. High-energy shockwaves and extracorporeal high-intensity focused ultrasound. J Endourol, 2003. 17: 667. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14622487/

34. Ramsay, C.R., et al. Ablative therapy for people with localised prostate cancer: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess, 2015. 19: 1. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26140518/

35. Ahmed, H.U., et al. Will focal therapy become a standard of care for men with localized prostate cancer? Nat Clin Pract Oncol, 2007. 4: 632. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17965641/

36. Eggener, S.E., et al. Focal therapy for localized prostate cancer: a critical appraisal of rationale and modalities. J Urol, 2007. 178: 2260. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17936815/

37. Crawford, E.D., et al. Targeted focal therapy: a minimally invasive ablation technique for early prostate cancer. Oncology (Williston Park), 2007. 21: 27. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17313155/

38. Lam, T.B.L., et al. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-SIOG Prostate Cancer Guideline Panel Consensus Statements for Deferred Treatment with Curative Intent for Localised Prostate Cancer from an International Collaborative Study (DETECTIVE Study). Eur Urol, 2019. 76: 790. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31587989/

39. Willemse, P.-P., et al. Systematic review of active surveillance for clinically localized prostate cancer to develop recommendations regarding inclusion of intermediate-risk disease, biopsy characteristics at inclusion and monitoring, and surveillance repeat biopsy strategy. Eur Urol, 2021. prior to print. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34980492/

40. Thomsen, F.B., et al. Active surveillance for clinically localized prostate cancer–a systematic review. J Surg Oncol, 2014. 109: 830. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24610744/

41. Loeb, S., et al. Active surveillance for prostate cancer: a systematic review of clinicopathologic variables and biomarkers for risk stratification. Eur Urol, 2015. 67: 619. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25457014/

42. Ha, Y.S., et al. Prostate-specific antigen density toward a better cutoff to identify better candidates for active surveillance. Urology, 2014. 84: 365. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24925834/

43. Immediate versus deferred treatment for advanced prostatic cancer: initial results of the Medical Research Council Trial. The Medical Research Council Prostate Cancer Working Party Investigators Group. Br J Urol, 1997. 79: 235. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9052476/

44. Briganti, A., et al. Updated nomogram predicting lymph node invasion in patients with prostate cancer undergoing extended pelvic lymph node dissection: the essential importance of percentage of positive cores. Eur Urol, 2012. 61: 480. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22078338/

45. Gandaglia, G., et al. A Novel Nomogram to Identify Candidates for Extended Pelvic Lymph Node Dissection Among Patients with Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer Diagnosed with Magnetic Resonance Imaging-targeted and Systematic Biopsies. Eur Urol, 2019. 75: 506. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30342844/

46. James, N.D., et al. Addition of docetaxel, zoledronic acid, or both to first-line long-term hormone therapy in prostate cancer (STAMPEDE): survival results from an adaptive, multiarm, multistage, platform randomised controlled trial. Lancet, 2016. 387: 1163. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26719232/

47. Krauss, D., et al. Lack of benefit for the addition of androgen deprivation therapy to dose-escalated radiotherapy in the treatment of intermediate- and high-risk prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2011. 80: 1064. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20584576/

48. Kupelian, P.A., et al. Effect of increasing radiation doses on local and distant failures in patients with localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2008. 71: 16. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17996382/

49. King, M.T., et al. Low dose rate brachytherapy for primary treatment of localized prostate cancer: A systemic review and executive summary of an evidence-based consensus statement. Brachytherapy, 2021. 20: 1114. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34509378/

50. Gandaglia, G., et al. Development and Internal Validation of a Novel Model to Identify the Candidates for Extended Pelvic Lymph Node Dissection in Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol, 2017. 72: 632. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28412062/

51. Bill-Axelson, A., et al. Radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting in early prostate cancer. N Engl J Med, 2014. 370: 932. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24597866/

52. Yaxley, J.W., et al. Robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy versus open radical retropubic prostatectomy: early outcomes from a randomised controlled phase 3 study. Lancet, 2016. 388: 1057. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27474375/

53. Bianco, F.J., Jr., et al. Radical prostatectomy: long-term cancer control and recovery of sexual and urinary function (“trifecta”). Urology, 2005. 66: 83. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16194712/

54. Walz, J., et al. A nomogram predicting 10-year life expectancy in candidates for radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy for prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol, 2007. 25: 3576. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17704404/

55. Allan, C., et al. Laparoscopic versus Robotic-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy for the Treatment of Localised Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review. Urol Int, 2016. 96: 373. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26201500/

56. Eastham, J.A., et al. Variations among individual surgeons in the rate of positive surgical margins in radical prostatectomy specimens. J Urol, 2003. 170: 2292. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14634399/

57. Vickers, A.J., et al. The surgical learning curve for laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol, 2009. 10: 475. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19342300/

58. Trinh, Q.D., et al. A systematic review of the volume-outcome relationship for radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol, 2013. 64: 786. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23664423/

59. Pisansky, T.M., et al. Correlation of pretherapy prostate cancer characteristics with histologic findings from pelvic lymphadenectomy specimens. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 1996. 34: 33. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12118563/

60. Joniau, S., et al. Pretreatment tables predicting pathologic stage of locally advanced prostate cancer. Eur Urol, 2015. 67: 319. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24684960/

61. Loeb, S., et al. Intermediate-term potency, continence, and survival outcomes of radical prostatectomy for clinically high-risk or locally advanced prostate cancer. Urology, 2007. 69: 1170. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17572209/

62. Carver, B.S., et al. Long-term outcome following radical prostatectomy in men with clinical stage T3 prostate cancer. J Urol, 2006. 176: 564. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16813890/

63. Freedland, S.J., et al. Radical prostatectomy for clinical stage T3a disease. Cancer, 2007. 109: 1273. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17315165/

64. Joniau, S., et al. Radical prostatectomy in very high-risk localized prostate cancer: long-term outcomes and outcome predictors. Scand J Urol Nephrol, 2012. 46: 164. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22364377/

65. Johnstone, P.A., et al. Radical prostatectomy for clinical T4 prostate cancer. Cancer, 2006. 106: 2603. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16700037/

66. Moris, L., et al. Benefits and Risks of Primary Treatments for High-risk Localized and Locally Advanced Prostate Cancer: An International Multidisciplinary Systematic Review. Eur Urol, 2020. 77: 614. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32146018/

67. Donohue, J.F., et al. Poorly differentiated prostate cancer treated with radical prostatectomy: longterm outcome and incidence of pathological downgrading. J Urol, 2006. 176: 991. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16890678/

68. Yossepowitch, O., et al. Radical prostatectomy for clinically localized, high risk prostate cancer: critical analysis of risk assessment methods. J Urol, 2007. 178: 493. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17561152/

69. Bastian, P.J., et al. Clinical and pathologic outcome after radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer patients with a preoperative Gleason sum of 8 to 10. Cancer, 2006. 107: 1265. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16900523/

70. Surgery Versus Radiotherapy for Locally Advanced Prostate Cancer (SPCG-15). 2014. [Access date March 2022]. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02102477

71.Ventimiglia, E., et al. A Systematic Review of the Role of Definitive Local Treatment in Patients with Clinically Lymph Node-positive Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol Oncol, 2019. 2: 294. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31200844/

72. Tward, J.D., et al. Radiation therapy for clinically node-positive prostate adenocarcinoma is correlated with improved overall and prostate cancer-specific survival. Pract Radiat Oncol, 2013. 3: 234. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24674370/

73. Lin, C.C., et al. Androgen deprivation with or without radiation therapy for clinically node-positive prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2015. 107. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25957435/

74. Seisen, T., et al. Efficacy of Local Treatment in Prostate Cancer Patients with Clinically Pelvic Lymph Node-positive Disease at Initial Diagnosis. Eur Urol, 2017. 73: 452. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28890245/

75. James, N.D., et al. Failure-Free Survival and Radiotherapy in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Nonmetastatic Prostate Cancer: Data from Patients in the Control Arm of the STAMPEDE Trial. JAMA Oncol, 2016. 2: 348. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26606329/

76. Rusthoven, C.G., et al. The impact of definitive local therapy for lymph node-positive prostate cancer: a population-based study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2014. 88: 1064. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24661660/

77. Wurnschimmel, C., et al. Radical prostatectomy for localized prostate cancer: 20-year oncological outcomes from a German high-volume center. Urol Oncol, 2021. 39: 830.e17. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34092484/

78. Bader, P., et al. Is a limited lymph node dissection an adequate staging procedure for prostate cancer? J Urol, 2002. 168: 514. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12131300/

79. Briganti, A., et al. Two positive nodes represent a significant cut-off value for cancer specific survival in patients with node positive prostate cancer. A new proposal based on a two-institution experience on 703 consecutive N+ patients treated with radical prostatectomy, extended pelvic lymph node dissection and adjuvant therapy. Eur Urol, 2009. 55: 261. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18838212/

80. Schumacher, M.C., et al. Good outcome for patients with few lymph node metastases after radical retropubic prostatectomy. Eur Urol, 2008. 54: 344. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18511183/

81. Abdollah, F., et al. More extensive pelvic lymph node dissection improves survival in patients with node-positive prostate cancer. Eur Urol, 2015. 67: 212. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24882672/

82. Pound, C.R., et al. Natural history of progression after PSA elevation following radical prostatectomy. JAMA, 1999. 281: 1591. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10235151/

83. Aus, G., et al. Prognostic factors and survival in node-positive (N1) prostate cancer-a prospective study based on data from a Swedish population-based cohort. Eur Urol, 2003. 43: 627. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12767363/

84. Cheng, L., et al. Risk of prostate carcinoma death in patients with lymph node metastasis. Cancer, 2001. 91: 66. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11148561/

85. Seiler, R., et al. Removal of limited nodal disease in patients undergoing radical prostatectomy: long-term results confirm a chance for cure. J Urol, 2014. 191: 1280. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24262495/

86. Passoni, N.M., et al. Prognosis of patients with pelvic lymph node (LN) metastasis after radical prostatectomy: value of extranodal extension and size of the largest LN metastasis. BJU Int, 2014. 114: 503. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24053552/

87. Daneshmand, S., et al. Prognosis of patients with lymph node positive prostate cancer following radical prostatectomy: long-term results. J Urol. 172: 2252. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15538242/

88. Touijer, K.A., et al. Long-term outcomes of patients with lymph node metastasis treated with radical prostatectomy without adjuvant androgen-deprivation therapy. Eur Urol, 2014. 65: 20. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23619390/

89. Fossati, N., et al. The Benefits and Harms of Different Extents of Lymph Node Dissection During Radical Prostatectomy for Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review. Eur Urol, 2017. 72: 84.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28126351/

90. Amling, C.L., et al. Defining prostate specific antigen progression after radical prostatectomy: what is the most appropriate cut point? J Urol, 2001. 165: 1146. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11257657/

91. Toussi, A., et al. Standardizing the Definition of Biochemical Recurrence after Radical Prostatectomy-What Prostate Specific Antigen Cut Point Best Predicts a Durable Increase and Subsequent Systemic Progression? J Urol, 2016. 195: 1754. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26721226/

92. Stephenson, A.J., et al. Defining biochemical recurrence of prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy: a proposal for a standardized definition. J Clin Oncol, 2006. 24: 3973. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16921049/

93. Van den Broeck, T., et al. Prognostic Value of Biochemical Recurrence Following Treatment with Curative Intent for Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review. Eur Urol, 2019. 75: 967. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30342843/

94. Jackson, W.C., et al. Intermediate Endpoints After Postprostatectomy Radiotherapy: 5-Year Distant Metastasis to Predict Overall Survival. Eur Urol, 2018. 74: 413. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29306514/

95. Choueiri, T.K., et al. Impact of postoperative prostate-specific antigen disease recurrence and the use of salvage therapy on the risk of death. Cancer, 2010. 116: 1887. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20162710/

96. Freiberger, C., et al. Long-term prognostic significance of rising PSA levels following radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer – focus on overall survival. Radiat Oncol, 2017. 12: 98. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28615058/

97. Royce, T.J., et al. Surrogate End Points for All-Cause Mortality in Men With Localized Unfavorable-Risk Prostate Cancer Treated With Radiation Therapy vs Radiation Therapy Plus Androgen Deprivation Therapy: A Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol, 2017. 3: 652. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28097317/

98. Zagars, G.K., et al. Kinetics of serum prostate-specific antigen after external beam radiation for clinically localized prostate cancer. Radiother Oncol, 1997. 44: 213. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9380819/

99. Rouviere, O., et al. Imaging of prostate cancer local recurrences: why and how? Eur Radiol, 2010. 20: 1254. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19921202/

100. Evangelista, L., et al. Choline PET or PET/CT and biochemical relapse of prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Nucl Med, 2013. 38: 305. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23486334/

101. Fanti, S., et al. PET/CT with (11)C-choline for evaluation of prostate cancer patients with biochemical recurrence: meta-analysis and critical review of available data. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging, 2016. 43: 55. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26450693/

102. Fuccio, C., et al. Role of 11C-choline PET/CT in the restaging of prostate cancer patients showing a single lesion on bone scintigraphy. Ann Nucl Med, 2010. 24: 485. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20544323/

103. Fuccio, C., et al. Role of 11C-choline PET/CT in the re-staging of prostate cancer patients with biochemical relapse and negative results at bone scintigraphy. Eur J Radiol, 2012. 81: e893. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22621862/

104. Mitchell, C.R., et al. Operational characteristics of (11)c-choline positron emission tomography/ computerized tomography for prostate cancer with biochemical recurrence after initial treatment. J Urol, 2013. 189: 1308. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23123372/

105. Soyka, J.D., et al. Clinical impact of 18F-choline PET/CT in patients with recurrent prostate cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging, 2012. 39: 936. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22415598/

106. Ceci, F., et al. Impact of 11C-choline PET/CT on clinical decision making in recurrent prostate cancer: results from a retrospective two-centre trial. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging, 2014. 41: 2222. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25182750/

107. Songmen, S., et al. Axumin Positron Emission Tomography: Novel Agent for Prostate Cancer Biochemical Recurrence. J Clin Imaging Sci, 2019. 9: 49. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31819826/

108. U.S. Food & Drug Adminstration. FDA approves new diagnostic imaging agent to detect recurrent prostate cancer – axumin. 2016. [Access date March 2022]. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-new-diagnostic-imagingagent-detect-recurrent-prostate-cancer

109. European Medicines Agency. Axumin 2017. [Access date March 2022]. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/

110. Nanni, C., et al. (18)F-FACBC (anti1-amino-3-(18)F-fluorocyclobutane-1-carboxylic acid) versus (11)C-choline PET/CT in prostate cancer relapse: results of a prospective trial. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging, 2016. 43: 1601. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26960562/

111. Perera, M., et al. Sensitivity, Specificity, and Predictors of Positive 68Ga-Prostate-specific Membrane Antigen Positron Emission Tomography in Advanced Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Eur Urol, 2016. 70: 926. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27363387/

112. Morigi, J.J., et al. Prospective Comparison of 18F-Fluoromethylcholine Versus 68Ga-PSMA PET/CT in Prostate Cancer Patients Who Have Rising PSA After Curative Treatment and Are Being Considered for Targeted Therapy. J Nucl Med, 2015. 56: 1185. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26112024/

113. Afshar-Oromieh, A., et al. Comparison of PET imaging with a (68)Ga-labelled PSMA ligand and (18)F-choline-based PET/CT for the diagnosis of recurrent prostate cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging, 2014. 41: 11. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24072344/

114. Van Nieuwenhove, S., et al. Whole-body magnetic resonance imaging for prostate cancer assessment: Current status and future directions. J Magn Reson Imaging, 2020. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33382151/

115. Eiber, M., et al. Whole-body MRI including diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) for patients with recurring prostate cancer: technical feasibility and assessment of lesion conspicuity in DWI. J Magn Reson Imaging, 2011. 33: 1160. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21509875/

116. Zacho, H.D., et al. Prospective comparison of (68)Ga-PSMA PET/CT, (18)F-sodium fluoride PET/ CT and diffusion weighted-MRI at for the detection of bone metastases in biochemically recurrent prostate cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging, 2018. 45: 1884. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29876619/

117. Luiting, H.B., et al. Use of gallium-68 prostate-specific membrane antigen positron-emission tomography for detecting lymph node metastases in primary and recurrent prostate cancer and location of recurrence after radical prostatectomy: an overview of the current literature. BJU Int, 2020. 125: 206. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31680398/

118. Farolfi, A., et al. (68)Ga-PSMA-11 PET/CT in prostate cancer patients with biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy and PSA <0.5 ng/ml. Efficacy and impact on treatment strategy. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging, 2019. 46: 11. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29905907/

119. Boreta, L., et al. Location of Recurrence by Gallium-68 PSMA-11 PET Scan in Prostate Cancer Patients Eligible for Salvage Radiotherapy. Urology, 2019. 129: 165. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30928607/

120. Guberina, N., et al. Whole-Body Integrated [(68)Ga]PSMA-11-PET/MR Imaging in Patients with Recurrent Prostate Cancer: Comparison with Whole-Body PET/CT as the Standard of Reference. Mol Imaging Biol, 2020. 22: 788. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31482413/

121. Metser, U., et al. The Contribution of Multiparametric Pelvic and Whole-Body MRI to Interpretation of (18)F-Fluoromethylcholine or (68)Ga-HBED-CC PSMA-11 PET/CT in Patients with Biochemical Failure After Radical Prostatectomy. J Nucl Med, 2019. 60: 1253. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30902875/

122. Freitag, M.T., et al. Local recurrence of prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy is at risk to be missed in (68)Ga-PSMA-11-PET of PET/CT and PET/MRI: comparison with mpMRI integrated in simultaneous PET/MRI. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging, 2017. 44: 776. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27988802/

123. Donati, O.F., et al. Multiparametric prostate MR imaging with T2-weighted, diffusion-weighted, and dynamic contrast-enhanced sequences: are all pulse sequences necessary to detect locally recurrent prostate cancer after radiation therapy? Radiology, 2013. 268: 440. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23481164/

124. Abd-Alazeez, M., et al. Multiparametric MRI for detection of radiorecurrent prostate cancer: added value of apparent diffusion coefficient maps and dynamic contrast-enhanced images. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis, 2015. 18: 128. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25644248/

125. Alonzo, F., et al. Detection of locally radio-recurrent prostate cancer at multiparametric MRI: Can dynamic contrast-enhanced imaging be omitted? Diagn Interv Imaging, 2016. 97: 433. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26928245/

126. Dinis Fernandes, C., et al. Quantitative 3T multiparametric MRI of benign and malignant prostatic tissue in patients with and without local recurrent prostate cancer after external-beam radiation therapy. J Magn Reson Imaging, 2019. 50: 269. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30585368/

127. Dinis Fernandes, C., et al. Quantitative 3-T multi-parametric MRI and step-section pathology of recurrent prostate cancer patients after radiation therapy. Eur Radiol, 2019. 29: 4160. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30421016/

128. Boorjian, S.A., et al. Radiation therapy after radical prostatectomy: impact on metastasis and survival. J Urol, 2009. 182: 2708. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19836762/

129. Stish, B.J., et al. Improved Metastasis-Free and Survival Outcomes With Early Salvage Radiotherapy in Men With Detectable Prostate-Specific Antigen After Prostatectomy for Prostate Cancer. J Clin Oncol, 2016. 34: 3864. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27480153/

130. Pfister, D., et al. Early salvage radiotherapy following radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol, 2014. 65: 1034. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23972524/

131. Siegmann, A., et al. Salvage radiotherapy after prostatectomy – what is the best time to treat? Radiother Oncol, 2012. 103: 239. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22119375/

132. Ohri, N., et al. Can early implementation of salvage radiotherapy for prostate cancer improve the therapeutic ratio? A systematic review and regression meta-analysis with radiobiological modelling. Eur J Cancer, 2012. 48: 837. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21945099/

133. Wiegel, T., et al. Achieving an undetectable PSA after radiotherapy for biochemical progression after radical prostatectomy is an independent predictor of biochemical outcome–results of a retrospective study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2009. 73: 1009. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18963539/

134. Tilki, D., et al. External Validation of the European Association of Urology Biochemical Recurrence Risk Groups to Predict Metastasis and Mortality After Radical Prostatectomy in a European Cohort. Eur Urol, 2019. 75: 896. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30955970/

135. Boorjian, S.A., et al. Long-term risk of clinical progression after biochemical recurrence following radical prostatectomy: the impact of time from surgery to recurrence. Eur Urol, 2011. 59: 893. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21388736/

Author Correspondence:

Prof. Dr. Semir A. Salim. Al Samarrai

Medical Director of Professor Al Samarrai Medical Center.

Dubai Healthcare City, Al-Razi Building 64, Block D, 2nd Floor, Suite 2018

E-mail: semiralsamarrai@hotmail.com

Tel: +97144233669