Prostate Cancer

Salvage Therapy

Comprehensive Review Article

Part 7

Prof. Dr. Semir. A. Salim. Al Samarrai

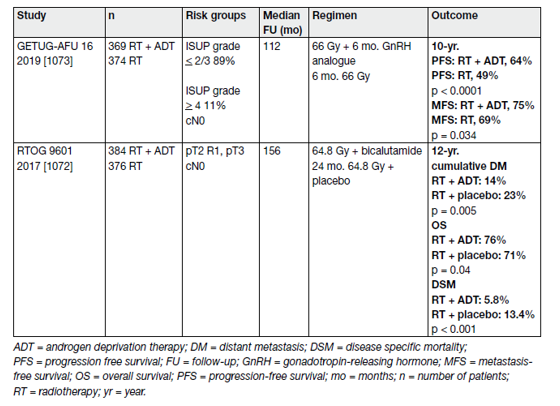

Salvage radiotherapy combined with androgen deprivation therapy (cTxcN0, without PET/CT):

Data from RTOG 9601 suggest both CSS and OS benefit when adding 2 years of bicalutamide (150 mg o.d.) to SRT [1].

However, SRT combined with either goserelin or placebo showed similar DSS and OS rates [2]. Table 1 provides an overview of these two RCTs.

Table 1. Randomised controlled trials comparing salvage radiotherapy combined with androgen deprivation therapy vs. salvage radiotherapy alone

- Target volume, dose, toxicity

There have been various attempts to define common outlines for ‘clinical target volumes‘ of PCa [3–6] and for organs at risk of normal tissue complications [7].

A benefit in biochemical PFS but not metastasis-free survival has been reported in patients receiving whole pelvis SRT (± ADT) but the advantages must be weighed against possible side effects [8].

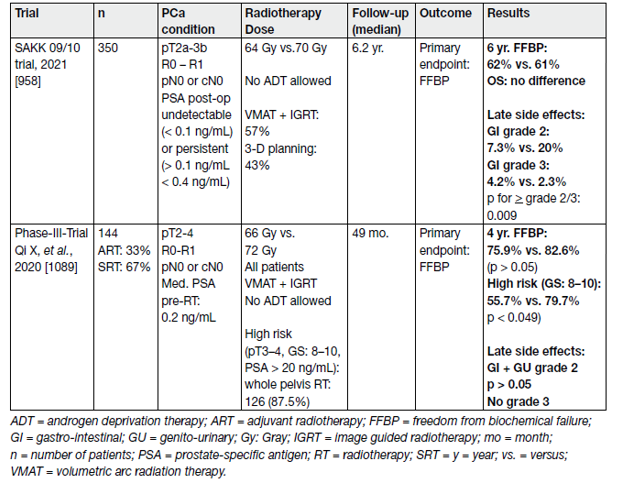

Two RCT’s were recently published (Table 2). Intensity-modulated radiation therapy plus IGRT was used in 57% of the patients in the SAKK-trial [9] and in all patients of the Chinese trial [10]. No patient had a PSMA PET/CT before randomisation.

Table 2. Randomized trials investigating dose escalation for SRT without ADT and without PET-CT

Salvage RT is associated with toxicity. In one report on 464 SRT patients receiving median 66.6 (max. 72) Gy, acute grade 2 toxicity was recorded in 4.7% for both the GI and GU tract. Two men had late grade 3 reactions of the GI tract, but overall, severe GU tract toxicity was not observed. Late grade 2 complications occurred in 4.7% (GI tract) and 4.1% (GU tract), respectively, and 4.5% of the patients developed moderate urethral stricture [11].

- Salvage RT with or without ADT (cTx CN0/1) with PET/CT

In a prospective multi-centre study of 323 patients with BCR, PSMA PET/CT changed the management intent in 62% of patients as compared to conventional staging. This was due to a significant reduction in the number of men in whom the site of disease recurrence was unknown (77% vs. 19%, p < 0.001) and a significant increase in the number of men with metastatic disease (11% vs. 57%) [12].

- Metastasis-directed therapy for rcN+ (with PET/CT)

Radiolabelled PSMA PET/CT is increasingly used as a diagnostic tool to assess metastatic disease burden in patients with BCR following prior definitive therapy. A review including 30 studies and 4,476 patients showed overall estimates of positivity in a restaging setting of 38% in pelvic LNs and 13% in extra-pelvic LN metastases [13]. The percentage positivity of PSMA PET/CT was proven to increase with higher PSA values, from 33% (95% CI: 16–51) for a PSA of < 0.2 ng/mL, to 45% (39–52), 59% (50–68), 75% (66–84), and 95% (92–97) for PSA subgroup values of 0.2–0.49, 0.5–0.99, 1.00–1.99, and > 2.00 ng/mL, respectively [13].

- Salvage lymph node dissection

The surgical management of (recurrent) nodal metastases in the pelvis has been the topic of several retrospective analyses [14-16] and a systematic review [17]. The reported 5-year BCR-free survival rates ranged from 6% to 31%. Five-year OS was approximately 84% [17]. Biochemical recurrence rates were found to be dependent on PSA at surgery and location and number of positive nodes [18]. Addition of RT to the lymphatic template after salvage LN dissection may improve the BCR rate [19].

- Management of PSA failures after radiation therapy

Therapeutic options in these patients are ADT or salvage local procedures. A systematic review and metaanalysis included studies comparing the efficacy and toxicity of salvage RP, salvage HIFU, salvage cryotherapy, SBRT, salvage LDR brachytherapy, and salvage HDR brachytherapy in the management of locally recurrent PCa after primary radical EBRT [20]. The outcomes were BCR-free survival at 2 and 5 years.

- Salvage radical prostatectomy

Salvage RP after RT is associated with a higher likelihood of adverse events (AEs) compared to primary surger because of the risk of fibrosis and poor wound healing due to radiation [21].

- Oncological outcomes

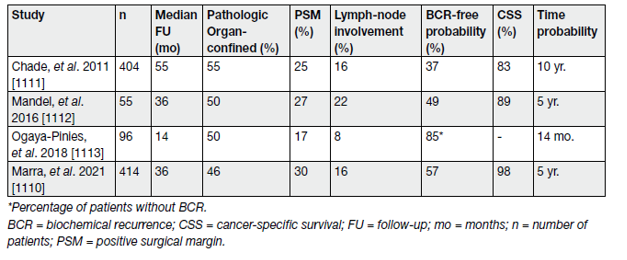

In a systematic review of the literature, Chade, et al., showed that SRP provided 5- and 10-year BCR-free survival estimates ranging from 47–82% and from 28–53%, respectively. The 10-year CSS and OS rates ranged from 70–83% and from 54–89%, respectively.

Pathological T stage > T3b (OR: 2.348) and GS (up to OR 7.183 for GS > 8) were independent predictors for BCR (see Table 3).

Table 3. Oncological results of selected salvage radical prostatectomy case series

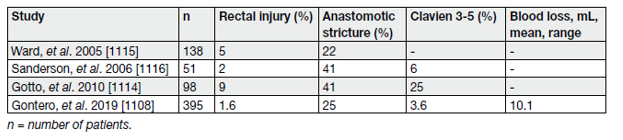

- Morbidity

Compared to primary open RP, SRP is associated with a higher risk of later anastomotic stricture (47 vs. 5.8%), urinary retention (25.3% vs. 3.5%), urinary fistula (4.1% vs. 0.06%), abscess (3.2% vs. 0.7%) and rectal injury (9.2 vs. 0.6%) [22]. In more recent series, these complications appear to be less common [21,23,24].

Functional outcomes are also worse compared to primary surgery, with urinary incontinence ranging from 21% to 90% and ED in nearly all patients (see table 4) [23,24].

Table 4. Peri-operative morbidity in selected salvage radical prostatectomy case series

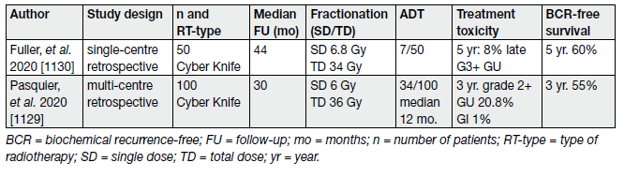

Stereotactic ablative body radiotherapy (CyberKnifeR or linac-based treatment) is a potentially viable new option to treat local recurrence after RT. Carefully selected patients with good IPSS-score, without obstruction, good PS and histologically proven localised local recurrence are potential candidates for SABR.

Table 5 summarises the results of the two larger SABR series addressing oncological outcomes and morbidity.

Table 5. Treatment-related toxicity and BCR-free survival in selected SABR studies including at least 50 patients

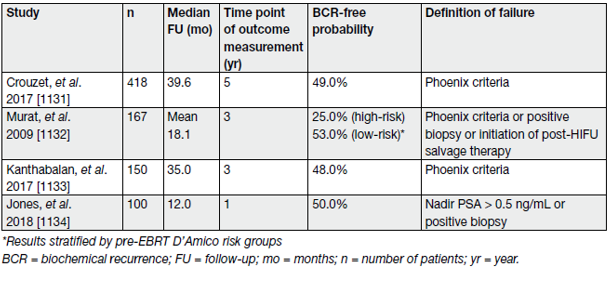

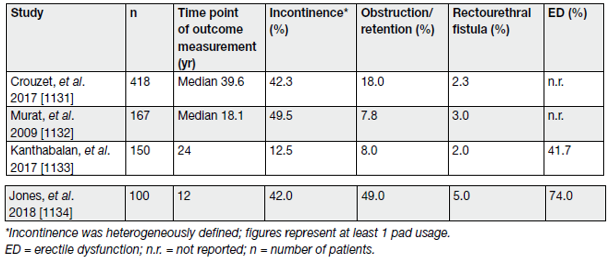

- Salvage high-intensity focused ultrasound

Salvage HIFU has emerged as an alternative thermal ablation option for radiation-recurrent PCa. Being relatively newer than SCAP the data for salvage HIFU are even more limited. A systematic review and metaanalysis included 20 studies (n = 1,783) assessing salvage HIFU [20]. The overwhelming majority of patients (86%) received whole-gland salvage HIFU. The adjusted pooled analysis for 2-year BCR-free survival for salvage HIFU was 54.14% (95% CI: 47.77–60.38%) and for 5-year BCR-free survival 52.72% (95% CI: 42.66–62.56%). However, the certainty of the evidence was low. Table 6 summarises the results of a selection of the largest series on salvage HIFU to date in relation to oncological outcomes (BCR only).

Table 6. Oncological results of selected salvage cryoablation of the prostate case series, including at least 250 patients

- Morbidity

The main adverse effects and complications relating to salvage HIFU include urinary incontinence, urinary retention due to bladder outflow obstruction, rectourethral fistula and ED. The systematic review and meta-analysis showed an adjusted pooled analysis for severe GU toxicity for salvage HIFU of 22.66% (95% CI: 16.98–28.85%) [20]. The certainty of the evidence was low. Table 7 summarises the results of a selection of the largest series on salvage HIFU to date in relation to GU outcomes.

Table 7. Peri-operative morbidity, erectile function and urinary incontinence in selected salvage HIFU case series, including at least 100 patients

There is a lack of high-certainty data which prohibits any recommendations regarding the indications for salvage HIFU in routine clinical practice. There is also a risk of significant morbidity associated with its use in the salvage setting. Consequently, salvage HIFU should only be performed in selected patients in experienced centres as part of a clinical trial or well-designed prospective cohort study.

- Hormonal therapy for relapsing patients

The European Association of Urology Guidelines 2022 conducted a systematic review including studies published from 2000 onwards [25]. Conflicting results were found on the clinical effectiveness of HT after previous curative therapy of the primary tumour.

The studied population is highly heterogeneous regarding their tumour biology and therefore clinical course. Predictive factors for poor outcomes were; CRPC, distant metastases, CSS, OS, short PSA-DT, high ISUP grade, high PSA, increased age and co-morbidities.

Non-steroidal anti-androgens have been claimed to be inferior compared to castration, but this difference was not seen in M0 patients [26]. One of the included RCTs suggested that intermittent HT is not inferior to continuous HT in terms of OS and CSS [27].

For older patients and those with co-morbidities the side effects of HT may even decrease life expectancy; in particular cardiovascular risk factors need to be considered [28,29]. Early HT should be reserved for those at the highest risk of disease progression defined mainly by a short PSA-DT at relapse (< 6–12 months) or a high initial ISUP grade (> 2/3) and a long life expectancy.

In unselected relapsing patients the median actuarial time to the development of metastasis will be 8 years and the median time from metastasis to death will be a further 5 years [30]. For patients with EAU Low-Risk BCR features, unfit patients with a life expectancy of less than 10 years or patients unwilling to undergo salvage treatment, active follow-up may represent a viable option.

- Treatment: Metastatic prostate cancer

Median survival of patients with newly diagnosed metastases is approximately 42 months with ADT alone, however, it is highly variable since the M1 population is heterogeneous [31]. Several prognostic factors for survival have been suggested including the number and location of bone metastases, presence of visceral metastases, ISUP grade, PS status and initial PSA alkaline phosphatase, but only few have been validated [32–35].

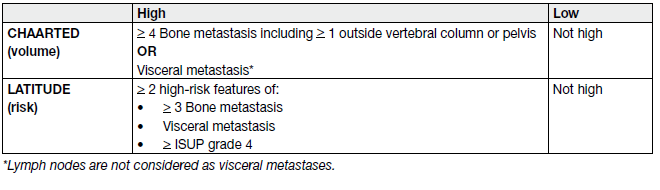

‘Volume‘ of disease as a potential predictor was introduced by CHAARTED (Chemo-hormonal Therapy versus Androgen Ablation Randomized Trial for Extensive Disease in Prostate Cancer) [35-37] and has been shown to be predictive in a powered subgroup analysis for benefit of addition of prostate RT ADT [38].

‘Metachronous’ metastatic disease vs. synchronous (or de novo) metastatic disease has also been shown to have a better prognosis [39].

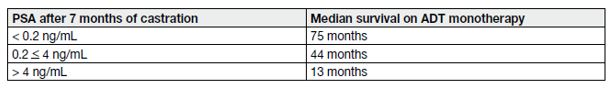

Based on a large SWOG 9346 cohort, the PSA level after 7 months of ADT was used to create 3 prognostic groups (see Table 8 and 9) [40].

Table 8. Definition of high- and low-volume and risk in CHAARTED and LATITIDE

Table 9. Prognostic factors based on the SWOG 9346 study

- First-line hormonal treatment

Primary ADT has been the SOC for over 50 years [41]. There is no high-level evidence in favour of a specific type of ADT for oncological outcomes, neither for orchiectomy nor for a LHRH agonist or antagonist. The level of testosterone is reduced much faster with orchiectomy and LHRH antagonist, therefore patients with impending spinal cord compression or other potential impending complications from the cancer should be treated with either a bilateral orchidectomy or LHRH antagonists as the preferred options.

There is a suggestion in some studies that cardiovascular side effects are less frequent in patients treated with LHRH antagonists vs. in patients treated with LHRH agonists [42,43,44]; therefore patients with pre-existing cardiovascular disease or other cardio-vascular risk factors might be considered to be treated with antagonists if a chemical castration is chosen.

- The non-steroidal anti-androgen monotherapy

Based on a Cochrane review comparing non-steroidal anti-androgen (NSAA) monotherapy to castration (either medical or surgical), NSAA was considered to be less effective in terms of OS, clinical progression, treatment failure and treatment discontinuation due to AEs [45]. The evidence quality of the studies included in this review was rated as moderate.

- The Intermittent versus continuous androgen deprivation therapy

Three independent reviews [46–48] and two meta-analyses [49,50] looked at the clinical efficacy of intermittent androgen deprivation (IAD) therapy. All of these reviews included 8 RCTs of which only 3 were conducted in patients with exclusively M1 disease. The 5 remaining trials included different patient groups, mainly locally-advanced and metastatic patients relapsing.

So far, the SWOG 9346 is the largest trial addressing IAD in M1b patients [51]. Out of 3,040 screened patients, only 1,535 patients met the inclusion criteria. This highlights that, at best, only 50% of M1b patients can be expected to be candidates for IAD, i.e. the best PSA responders.

There is a trend favouring IAD in terms of QoL, especially regarding treatment-related side effects such as hot flushes [52,53].

- Early versus deferred androgen deprivation therapy

There is an increasing body of evidence that early start of hormonal treatment also for the newer generation hormonal treatments is beneficial. Early treatment before the onset of symptoms is recommended in the majority of patients with metastatic hormone-sensitive disease despite lack of randomised phase III data in this specific setting and specifically not with the combination therapies that are standard nowadays.

- Combination therapies

All of the following combination therapies have been studied with continuous ADT, not intermittent ADT.

- Complete androgen blockade with older generation NSAA

The largest RCT in 1,286 M1b patients found no difference between surgical castration with or without flutamide [54]. However, results with other anti-androgens or castration modalities have differed and systematic reviews have shown that CAB using a NSAA appears to provide a small survival advantage (< 5%) vs. monotherapy (surgical castration or LHRH agonists) [55,56] beyond 5 years of survival [57] but this minimal advantage in a small subset of patients must be balanced against the increased side effects associated with long-term use of NSAAs. In addition, the newer combination therapies are more effective as shown specifically for enzalutamide vs. NSAA in a phase III trial [58], therefore combination with NSAAs should only be considered if the other combination therapies are not available.

- Androgen deprivation combined with other agents

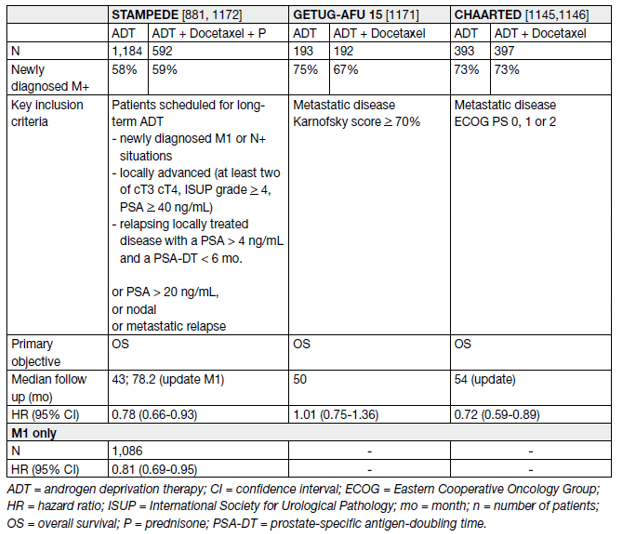

Three large RCTs were conducted [59,35,60]. All trials compared ADT alone as the SOC with ADT combined with immediate docetaxel (75 mg/sqm, every 3 weeks within 3 months of ADT initiation). The primary objective in all three studies was to assess OS. The key findings are summarized in Table 10.

Table 10. Key findings – Hormonal treatment combined with chemotherapy

Primary or secondary prophylaxis with GCSF should be based on available guidelines [61,62].

Based on these data, upfront docetaxel combined with ADT should be considered as a standard in men presenting with metastases at first presentation, provided they are fit enough to receive the drug [62].

- Combination with the new hormonal treatments (abiraterone, apalutamide, enzalutamide)

Docetaxel is used at the standard dose of 75 mg/sqm combined with steroids as pre-medication. Continuous oral corticosteroid therapy is not mandatory.

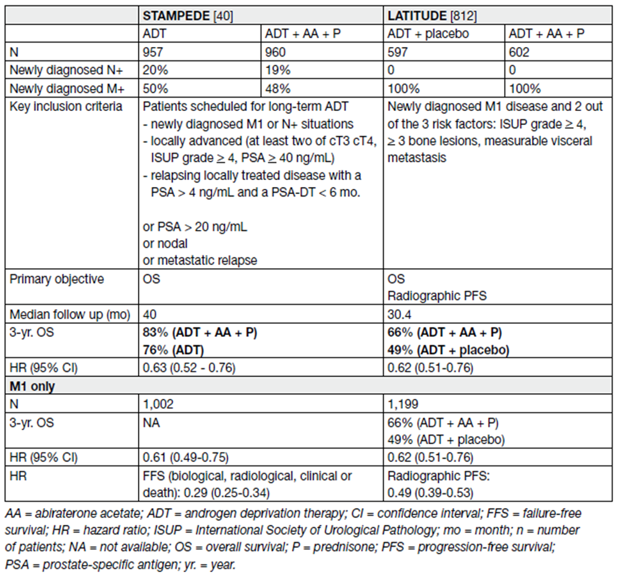

In two large RCTs (STAMPEDE, LATITUDE) the addition of abiraterone acetate (1000 mg daily) plus prednisone (5 mg daily) to ADT in men with mHSPC was studied [63,64,65]. The primary objective of both trials was an improvement in OS. Both trials showed a significant OS benefit. In LATITUDE with only high-risk metastatic patients included, the HR reached 0.62 (0.51–0.76) [64]. The HR in STAMPEDE was very similar with 0.63 (0.52–0.76) in the total patient population (metastatic and non-metastatic) and a HR of 0.61 in the subgroup of metastatic patients [63]. While only high-risk patients were included in the LATITUDE trial a post-hoc analysis from STAMPEDE showed the same benefit whatever the risk or the volume stratification [66].

All secondary objectives such as PFS, time to radiographic progression, time to pain, or time to chemotherapy were positive and in favour of the combination. The key findings are summarised in Table 11.

Table 11. Results from the STAMPEDE arm G and LATITUDE studies

No difference in treatment-related deaths was observed with the combination of ADT plus AAP compared to ADT monotherapy (HR: 1.37 [0.82–2.29]).

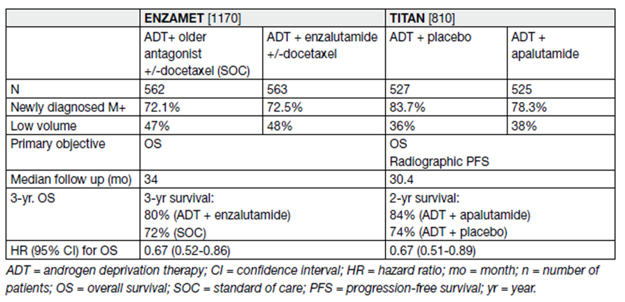

In summary, the addition of the new AR antagonists significantly improves clinical outcomes with no convincing evidence of differences between subgroups. The majority of patients treated had de novo metastatic disease and the evidence is most compelling in this situation. In the trials with the new AR antagonists, a proportion of patients had metachronous disease (see Table 12).

Table 12. Results from the ENZAMET and TITAN studies

Therefore, a combination should also be considered for men progressing after radical local therapy. Lastly, whether the addition of a new AR antagonist plus docetaxel adds further OS benefit is currently unclear.

The addition of abiraterone to ADT and docetaxel has been reported to have a benefit in rPFS and in OS in the PEACE-1 trial [67].

- Treatment selection and patient selection

An ADT-based combination therapy is the SOC for patients with newly diagnosed mHSPC. There are no head-to-head data comparing 6 cycles of docetaxel and the continuous use of AAP or of apalutamide or of enzalutamide in newly diagnosed mHSPC. However, for a period, patients in STAMPEDE were randomised to either the addition of abiraterone or docetaxel to SOC.

There have been several network meta-analyses of the published data concluding that combination therapy is more efficient than ADT alone, but none of the combination therapies has been clearly proven to be superior over another [68,69]. As a consequence, patients should be offered combination treatment unless there are clear contra-indications or they present with asymptomatic disease and a very short life expectancy (based on non-cancer co-morbidities).

- Treatment of the primary tumour in newly diagnosed metastatic disease

The doses and template used in STAMPEDE should be considered (55 Gy in 20 daily fractions over 4 weeks or 36 Gy in 6-weekly fractions of 6 Gy or a biological equivalent total dose of 72 Gy). Therefore, RT of the prostate only in patients with low-volume metastatic disease should be considered.

Of note, only 18% of these patients had additional docetaxel and no patients had additional AAP, so no clear recommendation can be made about triple combinations. In addition, it is not clear if these data can be extrapolated to RP as local treatment as results of ongoing trials are awaited.

In a systematic review and meta-analysis including the above two RCTs, the authors found that, overall, there was no evidence that the addition of prostate RT to ADT improved survival in unselected patients (HR: 0.92, 95% CI: 0.81–1.04, p = 0.195) [70].

- Metastasis-directed therapy in M1-patients

In patients relapsing after a local treatment, a metastases-targeting therapy has been proposed, with the aim to delay systemic treatment.

Oligo-recurrence was defined as < 3 lesions on choline-PET/CT only [71] or conventional imaging with MRI/CT and/or bone scan [72].

Two comprehensive reviews highlighted MDT (SABR) as a promising therapeutic approach that must still be considered as experimental until the results of the ongoing RCT are available [73,74].

Treatment:

- Castration-resistant PCa (CRPC)

The definition of CRPC is when Castrate serum testosterone < 50 ng/dL or 1.7 nmol/L plus either:

a. Biochemical progression: Three consecutive rises in PSA at least one week apart resulting in two 50% increases over the nadir, and a PSA > 2 ng/mL or

b. Radiological progression: The appearance of new lesions: either two or more new bone lesions on bone scan or a soft tissue lesion using RECIST (Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours) [75].

Symptomatic progression alone must be questioned and subject to further investigation. It is not sufficient to diagnose CRPC.

- The management of mCRPC – general aspects

Selection of treatment for mCRPC is multifactorial and in general dependent on:

• previous treatment for mHSPC and for non-mHSPC;

• previous treatment for mCRPC;

• quality of response and pace of progression on previous treatment;

• known cross resistance between androgen receptor targeted agents (ARTA);

• co-medication and known drug interactions (see approved summary of product characteristics);

• known genetic alterations and microsatellite instability–high (MSI-H)/mismatch repair–deficient (dMMR) status;

• known histological variants and DNA repair deficiency (consider platinum or targeted therapy like PARPi;

• local approval status of drugs and reimbursement situation;

• available clinical trials;

• The patient and his co-morbidities.

- The molecular diagnosis

The molecular diagnosis should be offered, that means all metastatic patients should be offered somatic genomic testing for homologous repair and MMR defects,

preferably on metastatic carcinoma tissue but testing on primary tumour may also be performed. Alternatively, but still less common, genetic testing on circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA) is an option and has been used in some trials. One test, the FoundationOneR Liquid CDx, has been FDA approved [76].

Defective MMR assessment can be performed by IHC for MMR proteins (MSH2, MSH6, MLH1 and PMS2) and/or by nextgeneration sequencing (NGS) assays [77]. Germline testing for BRCA1/2, ATM and MMR is recommended for high-risk and particularly for metastatic PCa if clinically indicated.

Level 1 evidence for the use of PARP-inhibitors has been reported [78–80]. Microsatellite instability (MSI)-high (or MMR deficiency) is rare in PCa, but for those patients, pembrolizumab has been approved by the FDA and could be a valuable additional treatment option [81,82].

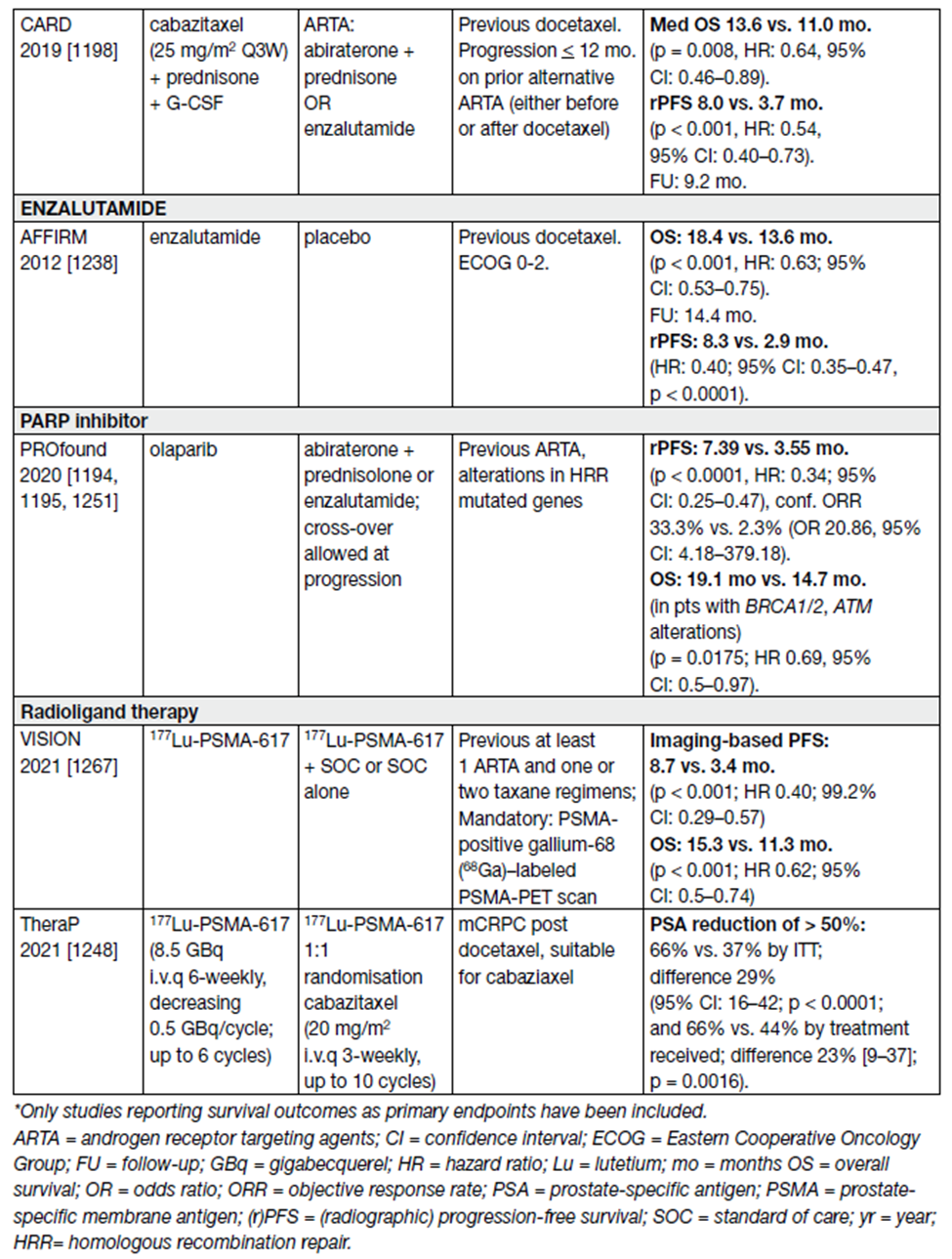

- Treatment decisions and sequence of available options

Approved agents for the treatment of mCRPC in Europe are docetaxel, abiraterone/prednisolone, enzalutamide, cabazitaxel, olaparib and radium-223. In general, sequencing of ARTAs like abiraterone and enzalutamide is not recommended particularly if the time of response to ADT and to the first ARTA was short (< 12 months) and high-risk features of rapid progression are present [83,84].

The use of chemotherapy with docetaxel and subsequent cabazitaxel in the treatment sequence is recommended and should be applied early enough when the patient is still fit for chemotherapy. This is supported by high-level evidence [83].

- Non-metastatic CRPC

Frequent PSA testing in men treated with ADT has resulted in earlier detection of biochemical progression.

Of these men approximately one-third will develop bone metastases within two years, detected by conventional imaging [85].

In men with CRPC and no detectable clinical metastases using bone scan and CT-scan, baseline PSA level, PSA velocity and PSA-DT have been associated with time to first bone metastasis, bone metastasisfree survival and OS [85,86]. These factors may be used when deciding which patients should be evaluated for metastatic disease. A consensus statement by the PCa Radiographic Assessments for Detection

of Advanced Recurrence (RADAR) group suggested a bone scan and a CT scan when the PSA reached 2 ng/mL and if this was negative, it should be repeated when the PSA reached 5 ng/mL, and again after every doubling of the PSA based on PSA testing every three months in asymptomatic men [87].

Symptomatic patients should undergo relevant investigations regardless of PSA level. With more sensitive imaging techniques like PSMA PET/CT or whole-body MRI, more patients are diagnosed with early mCRPC [88]. It remains unclear if the use of PSMA PET/CT in this setting improves outcome.

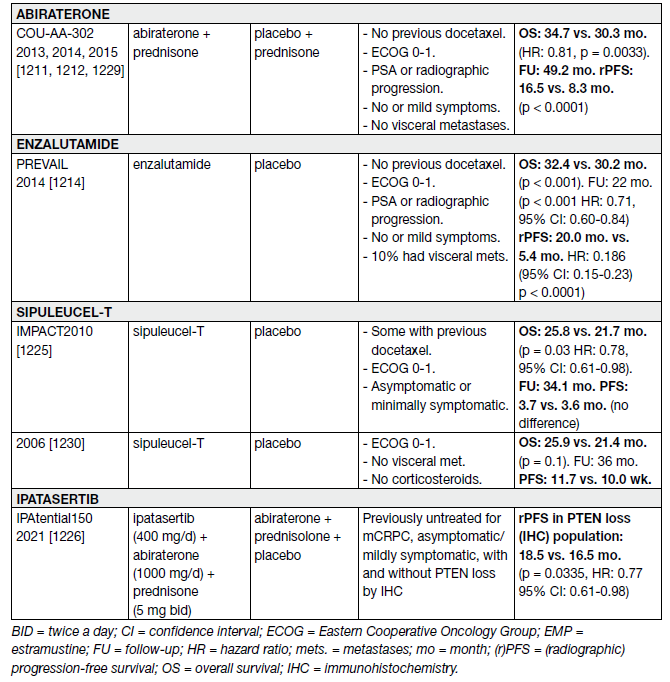

- First-line treatment of metastatic CRPC

Abiraterone was evaluated in 1,088 chemo-naive, asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic mCRPC patients in the phase III COU-AA-302 trial.

At the final analysis with a median follow-up of 49.2 months, the OS endpoint was significantly positive (34.7 vs. 30.3 months, HR: 0.81, 95% CI: 0.70–0.93, p = 0.0033) [89]. Adverse events related to mineralocorticoid excess and liver function abnormalities were more frequent with abiraterone, but mostly grade 1–2. Subset analysis of this trial showed the drug to be equally effective in an elderly population (> 75 years) [90].

Enzalutamide was equally effective and well tolerated in men > 75 years [91] as well as in those with or without visceral metastases [92]. However, for men with liver metastases, there seemed to be no discernible benefit [92,93].

Enzalutamide has also been compared with bicalutamide 50 mg/day in a randomised double blind phase II study (TERRAIN) showing a significant improvement in PFS (15.7 months vs. 5.8 months, HR: 0.44, p < 0.0001) in favour of enzalutamide [93]. With extended follow-up and final analysis the benefit in OS and rPFS were confirmed [94].

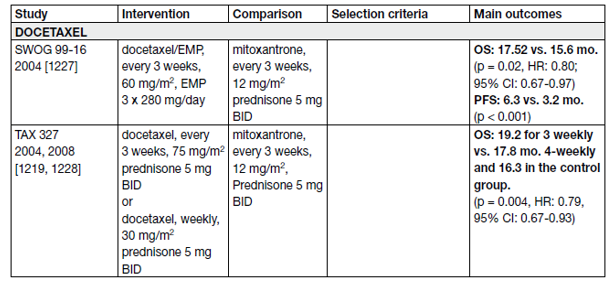

A statistically significant improvement in median survival of 2.0–2.9 months has been shown with docetaxelbased chemotherapy compared to mitoxantrone plus prednisone [95,96]. The standard first-line chemotherapy is docetaxel 75 mg/m2, 3-weekly doses combined with prednisone 5 mg twice a day (BID), up to 10 cycles. Prednisone can be omitted if there are contraindications or no major symptoms.

In men with mCRPC who are thought to be unable to tolerate the standard dose and schedule, docetaxel 50 mg/m2 every two weeks seems to be well tolerated with less grade 3–4 AEs and a prolonged time to treatment failure [97].

Table 13. Randomised phase III controlled trials – first-line treatment of mCRPC

- Second-line treatment for mCRPC and sequence

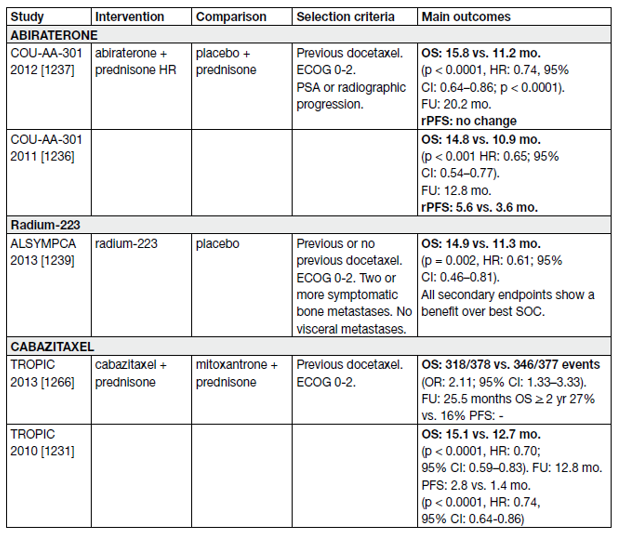

All patients who receive treatment for mCRPC will eventually progress. All treatment options in this setting are presented in Table 14. High-level evidence exists for second-line treatments after first-line treatment with docetaxel and for third-line therapy.

Table 14. Randomized controlled II/III – second-line/third-line trials in mCRPC

- Second-line treatment for mCRPC and sequencing of therapy

During the 90s several radiopharmaceuticals including phosphorous-32, strontium-89, yttrium-90, samarium-153, and rhenium-186 were developed for the treatment of bone pain secondary to metastasis from PCa [98]. They were effective at palliation; relieving pain and improving QoL, especially in the setting of diffuse bone metastasis. However, they never gained widespread adoption. The first radioisotope to demonstrate a survival benefit was radium-223.

- PSMA-based therapy

The increasing use of PSMA PET as a diagnostic tracer and the realisation that this allowed identification of a greater number of metastatic deposits led to attempts to treat cancer by replacing the imaging isotope with a therapeutic isotope which accumulates where the tumour is demonstrated (theranostics) [99].

Therefore, after identification of the target usually with diagnostic 68Gallium-labelled PSMA, therapeutic radiopharmaceuticals labelled with β (lutetium-177 or ytrium-90) or α(actinium-225)-emitting isotopes could be used to treat metastatic PCa.

More than 800 patients were randomised. 177Lu-PSMA-617 plus SOC significantly prolonged both imaging-based PFS and OS as compared with SOC alone (see Table 14).

Grade 3 or above AEs were higher with 177Lu-PSMA-617 than without (52.7% vs. 38.0%), but QoL was not adversely affected. 177Lu–PSMA-617 has shown to be a valuable additional treatment option in this mCRPC population [100].

- Immunotherapy for mCRPC

The immune checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab was approved by the FDA for all MMR–deficient cancers or in those with instable microsatellite status (MSI-high) [81]. This also applies to PCa but it is a very rare finding in this tumour entity [82].

- Platinum chemotherapy

Cisplatin or carboplatin as monotherapy or combinations have shown limited activity in unselected patients in the pre-docetaxel era [101].

Patients with mCRPC and alterations in DDR genes are more sensitive to platinum chemotherapy than unselected patients [102], also after progression on PARP inhibitors.

Preventing skeletal-related events:

- Bisphosphonates

Zoledronic acid has been evaluated in mCRPC to reduce skeletal-related events (SRE). This study was conducted when no active anti-cancer treatments, but for docetaxel, were available.

However, at 15 and 24 months of follow-up, patients treated with 4 mg zoledronic acid had fewer SREs compared to the placebo group (44 vs. 33%, p = 0.021) and in particular fewer pathological fractures (13.1 vs. 22.1%, p = 0.015).

- RANK ligand inhibitors

Denosumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody directed against RANKL (receptor activator of nuclear factor κ-B ligand), a key mediator of osteoclast formation, function, and survival. In M0 CRPC, denosumab has been associated with increased bone-metastasis-free survival compared to placebo (median benefit: 4.2 months, HR: 0.85, p = 0.028) [103].

The potential toxicity (e.g., osteonecrosis of the jaw, hypocalcaemia) of these drugs must always be kept in mind (5–8.2% in M0 CRPC and mCRPC, respectively) [104-106].

Daily calcium (> 500 mg) and vitamin D + (> 400 IU equivalent) are recommended in all patients, unless in case of hypercalcaemia [106,107,108].

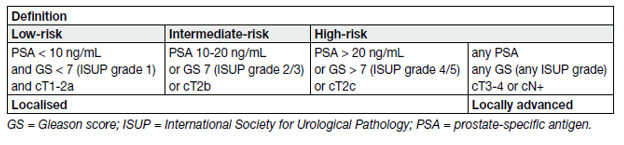

Table 15. EAU risk groups for biochemical recurrence of localised and locally advanced prostate cancer

REFERENCES:

1. Shipley, W., et al. Radiation with or without Antiandrogen Therapy in Recurrent Prostate Cancer. N Eng J Med, 2017. 376: 417. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28146658/

2. Carrie, C., et al. Short-term androgen deprivation therapy combined with radiotherapy as salvage treatment after radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer (GETUG-AFU 16): a 112-month follow-up of a phase 3, randomised trial. Lancet Oncol, 2019. 20: 1740. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31629656/

3. Michalski, J.M., et al. Development of RTOG consensus guidelines for the definition of the clinical target volume for postoperative conformal radiation therapy for prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2010. 76: 361. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19394158/

4. Poortmans, P., et al. Guidelines for target volume definition in post-operative radiotherapy for prostate cancer, on behalf of the EORTC Radiation Oncology Group. Radiother Oncol, 2007. 84: 121. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17706307/

5. Wiltshire, K.L., et al. Anatomic boundaries of the clinical target volume (prostate bed) after radical prostatectomy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2007. 69: 1090. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17967303/

6. Sassowsky, M., et al. Use of EORTC target definition guidelines for dose-intensified salvage radiation therapy for recurrent prostate cancer: results of the quality assurance program of the randomized trial SAKK 09/10. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2013. 87: 534. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23972722/

7. Gay, H.A., et al. Pelvic normal tissue contouring guidelines for radiation therapy: a Radiation Therapy Oncology Group consensus panel atlas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2012. 83: e353. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22483697/

8. Ramey, S.J., et al. Multi-institutional Evaluation of Elective Nodal Irradiation and/or Androgen Deprivation Therapy with Postprostatectomy Salvage Radiotherapy for Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol, 2018. 74: 99. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29128208/

9. Ghadjar, P., et al. Postoperative radiotherapy in prostate cancer. Lancet, 2021. 397: 1623. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33933203/

10. Qi, X., et al. Toxicity and Biochemical Outcomes of Dose-Intensified Postoperative Radiation Therapy for Prostate Cancer: Results of a Randomized Phase III Trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2020. 106: 282. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31669564/

11. Bartkowiak, D., et al. Prostate-specific antigen after salvage radiotherapy for postprostatectomy biochemical recurrence predicts long-term outcome including overall survival. Acta Oncol, 2018. 57: 362. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28816074/

12. Roach, P.J., et al. The Impact of (68)Ga-PSMA PET/CT on Management Intent in Prostate Cancer: Results of an Australian Prospective Multicenter Study. J Nucl Med, 2018. 59: 82. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28646014/

13. Krauss, D., et al. Lack of benefit for the addition of androgen deprivation therapy to dose-escalated radiotherapy in the treatment of intermediate- and high-risk prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2011. 80: 1064. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20584576/

14. Suardi, N., et al. Long-term outcomes of salvage lymph node dissection for clinically recurrent prostate cancer: results of a single-institution series with a minimum follow-up of 5 years. Eur Urol, 2015. 67: 299. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24571959/

15. Tilki, D., et al. Salvage lymph node dissection for nodal recurrence of prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy. J Urol, 2015. 193: 484. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25180792/

16. Fossati, N., et al. Identifying the Optimal Candidate for Salvage Lymph Node Dissection for Nodal Recurrence of Prostate Cancer: Results from a Large, Multi-institutional Analysis. Eur Urol, 2019. 75: 176. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30301694/

17. Ploussard, G., et al. Salvage Lymph Node Dissection for Nodal Recurrent Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review. Eur Urol, 2019. 76: 493. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30391078/

18. Ost, P., et al. Metastasis-directed therapy of regional and distant recurrences after curative treatment of prostate cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Eur Urol, 2015. 67: 852. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25240974/

19. Rischke, H.C., et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy after salvage lymph node dissection because of nodal relapse of prostate cancer versus salvage lymph node dissection only. Strahlenther Onkol, 2015. 191: 310. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25326142/

20. Valle, L.F., et al. A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Local Salvage Therapies After Radiotherapy for Prostate Cancer (MASTER). Eur Urol, 2021. 80: 280. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33309278/

21. Gontero, P., et al. Salvage Radical Prostatectomy for Recurrent Prostate Cancer: Morbidity and Functional Outcomes from a Large Multicenter Series of Open versus Robotic Approaches. J Urol, 2019. 202: 725. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31075058/

22. Gotto, G.T., et al. Impact of prior prostate radiation on complications after radical prostatectomy. J Urol, 2010. 184: 136. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20478594/

23. Chade, D.C., et al. Cancer control and functional outcomes of salvage radical prostatectomy for radiation-recurrent prostate cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Eur Urol, 2012. 61: 961. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22280856/

24. Mandel, P., et al. Salvage radical prostatectomy for recurrent prostate cancer: verification of European Association of Urology guideline criteria. BJU Int, 2016. 117: 55. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25711672/

25. van den Bergh, R.C., et al. Role of Hormonal Treatment in Prostate Cancer Patients with Nonmetastatic Disease Recurrence After Local Curative Treatment: A Systematic Review. Eur Urol, 2016. 69: 802. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26691493/

26. Trock, B.J., et al. Prostate cancer-specific survival following salvage radiotherapy vs observation in men with biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy. Jama, 2008. 299: 2760. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18560003/

27. Crook, J.M., et al. Intermittent androgen suppression for rising PSA level after radiotherapy. N Engl J Med, 2012. 367: 895. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22931259/

28. Levine, G.N., et al. Androgen-deprivation therapy in prostate cancer and cardiovascular risk: a science advisory from the American Heart Association, American Cancer Society, and American Urological Association: endorsed by the American Society for Radiation Oncology. Circulation, 2010. 121: 833. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20124128/

29. O’Farrell, S., et al. Risk and Timing of Cardiovascular Disease After Androgen-Deprivation Therapy in Men With Prostate Cancer. J Clin Oncol, 2015. 33: 1243. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25732167/

30. Pound, C.R., et al. Natural history of progression after PSA elevation following radical prostatectomy. JAMA, 1999. 281: 1591. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10235151/

31. James, N.D., et al. Survival with Newly Diagnosed Metastatic Prostate Cancer in the “Docetaxel Era”: Data from 917 Patients in the Control Arm of the STAMPEDE Trial (MRC PR08, CRUK/06/019). Eur Urol, 2015. 67: 1028. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25301760/

32. Glass, T.R., et al. Metastatic carcinoma of the prostate: identifying prognostic groups using recursive partitioning. J Urol, 2003. 169: 164. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12478127/

33. Gravis, G., et al. Prognostic Factors for Survival in Noncastrate Metastatic Prostate Cancer: Validation of the Glass Model and Development of a Novel Simplified Prognostic Model. Eur Urol, 2015. 68: 196. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25277272/

34. Gravis, G., et al. Androgen Deprivation Therapy (ADT) Plus Docetaxel Versus ADT Alone in Metastatic Non castrate Prostate Cancer: Impact of Metastatic Burden and Long-term Survival Analysis of the Randomized Phase 3 GETUG-AFU15 Trial. Eur Urol, 2016. 70: 256. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26610858/

35. Sweeney, C.J., et al. Chemohormonal Therapy in Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med, 2015. 373: 737. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26244877/

36. Kyriakopoulos, C.E., et al. Chemohormonal Therapy in Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer: Long-Term Survival Analysis of the Randomized Phase III E3805 CHAARTED Trial. J Clin Oncol, 2018. 36: 1080. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29384722/

37. Gravis, G., et al. Burden of Metastatic Castrate Naive Prostate Cancer Patients, to Identify Men More Likely to Benefit from Early Docetaxel: Further Analyses of CHAARTED and GETUG-AFU15 Studies. Eur Urol, 2018. 73: 847. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29475737/

38. Parker, C.C., et al. Radiotherapy to the primary tumour for newly diagnosed, metastatic prostate cancer (STAMPEDE): a randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet, 2018. 392: 2353. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30355464/

39. Francini, E., et al. Time of metastatic disease presentation and volume of disease are prognostic for metastatic hormone sensitive prostate cancer (mHSPC). Prostate, 2018. 78: 889. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29707790/

40. Hussain, M., et al. Absolute prostate-specific antigen value after androgen deprivation is a strong independent predictor of survival in new metastatic prostate cancer: data from Southwest Oncology Group Trial 9346 (INT-0162). J Clin Oncol, 2006. 24: 3984. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16921051/

41. Pagliarulo, V., et al. Contemporary role of androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. Eur Urol, 2012. 61: 11. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21871711/

42. Shore, N.D., et al. Oral Relugolix for Androgen-Deprivation Therapy in Advanced Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med, 2020. 382: 2187. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32469183/

43. Davey, P., et al. Cardiovascular risk profiles of GnRH agonists and antagonists: real-world analysis from UK general practice. World J Urol, 2021. 39: 307. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32979057/

44. Boland, J., et al. Cardiovascular Toxicity of Androgen Deprivation Therapy. Curr Cardiol Rep, 2021. 23: 109. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34216282/

45. Kunath, F., et al. Non-steroidal antiandrogen monotherapy compared with luteinising hormonereleasing hormone agonists or surgical castration monotherapy for advanced prostate cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2014. 6: CD009266. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24979481/

46. Niraula, S., et al. Treatment of prostate cancer with intermittent versus continuous androgen deprivation: a systematic review of randomized trials. J Clin Oncol, 2013. 31: 2029. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23630216/

47. Botrel, T.E., et al. Intermittent versus continuous androgen deprivation for locally advanced, recurrent or metastatic prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Urol, 2014. 14: 9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24460605/

48. Tsai, H.T., et al. Efficacy of intermittent androgen deprivation therapy vs conventional continuous androgen deprivation therapy for advanced prostate cancer: a meta-analysis. Urology, 2013. 82: 327. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23896094/

49. Brungs, D., et al. Intermittent androgen deprivation is a rational standard-of-care treatment for all stages of progressive prostate cancer: results from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis, 2014. 17: 105. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24686773/

50. Magnan, S., et al. Intermittent vs Continuous Androgen Deprivation Therapy for Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol, 2015. 1: 1261. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26378418/

51. Hussain, M., et al. Intermittent versus continuous androgen deprivation in prostate cancer. N Engl J Med, 2013. 368: 1314. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23550669/

52. Verhagen, P.C., et al. Intermittent versus continuous cyproterone acetate in bone metastatic prostate cancer: results of a randomized trial. World J Urol, 2014. 32: 1287. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24258313/

53. Calais da Silva, F., et al. Locally advanced and metastatic prostate cancer treated with intermittent androgen monotherapy or maximal androgen blockade: results from a randomised phase 3 study by the South European Uroncological Group. Eur Urol, 2014. 66: 232. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23582949/

54. Eisenberger, M.A., et al. Bilateral orchiectomy with or without flutamide for metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med, 1998. 339: 1036. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9761805/

55. Maximum androgen blockade in advanced prostate cancer: an overview of the randomised trials. Prostate Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group. Lancet, 2000. 355: 1491. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10801170/

56. Schmitt, B., et al. Maximal androgen blockade for advanced prostate cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2000: CD001526. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10796804/

57. Akaza, H., et al. Combined androgen blockade with bicalutamide for advanced prostate cancer: long-term follow-up of a phase 3, double-blind, randomized study for survival. Cancer, 2009. 115: 3437. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19536889/

58. Davis, I.D., et al. Enzalutamide with Standard First-Line Therapy in Metastatic Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med, 2019. 381: 121. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31157964/

59. James, N.D., et al. Addition of docetaxel, zoledronic acid, or both to first-line long-term hormone therapy in prostate cancer (STAMPEDE): survival results from an adaptive, multiarm, multistage, platform randomised controlled trial. Lancet, 2016. 387: 1163. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26719232/

60. Gravis, G., et al. Androgen-deprivation therapy alone or with docetaxel in non-castrate metastatic prostate cancer (GETUG-AFU 15): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol, 2013. 14: 149. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23306100/

61. Smith, T.J., et al. Recommendations for the Use of WBC Growth Factors: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol, 2015. 33: 3199. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26169616/

62. Sathianathen, N.J., et al. Taxane-based chemohormonal therapy for metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2018. 10: CD012816. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30320443/

63. James, N.D., et al. Abiraterone for Prostate Cancer Not Previously Treated with Hormone Therapy. N Engl J Med, 2017. 377: 338. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28578639/

64. Fizazi, K., et al. Abiraterone plus Prednisone in Metastatic, Castration-Sensitive Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med, 2017. 377: 352. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28578607/

65. Rydzewska, L.H.M., et al. Adding abiraterone to androgen deprivation therapy in men with

metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer, 2017. 84: 88. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28800492/

66. Hoyle, A.P., et al. Abiraterone in “High-” and “Low-risk” Metastatic Hormone-sensitive Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol, 2019. 76: 719. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31447077/

67. Fizazi, K., et al. A phase 3 trial with a 2×2 factorial design of abiraterone acetate plus prednisone and/or local radiotherapy in men with de novo metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (mCSPC): First results of PEACE-1. J Clin Oncol, 2021. 15 Suppl: 5000. https://ascopubs.org/doi/abs/10.1200/JCO.2021.39.15_suppl.5000

68. Marchioni, M., et al. New Antiandrogen Compounds Compared to Docetaxel for Metastatic Hormone Sensitive Prostate Cancer: Results from a Network Meta-Analysis. J Urol, 2020. 203: 751. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31689158/

69. Sathianathen, N.J., et al. Indirect Comparisons of Efficacy between Combination Approaches in Metastatic Hormone-sensitive Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. Eur Urol, 2020. 77: 365. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31679970/

70. Burdett, S., et al. Prostate Radiotherapy for Metastatic Hormone-sensitive Prostate Cancer: A STOPCAP Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Eur Urol, 2019. 76: 115. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30826218/

71. Ost, P., et al. Surveillance or Metastasis-Directed Therapy for Oligometastatic Prostate Cancer Recurrence: A Prospective, Randomized, Multicenter Phase II Trial. J Clin Oncol, 2018. 36: 446. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29240541/

72. Phillips, R., et al. Outcomes of Observation vs Stereotactic Ablative Radiation for Oligometastatic Prostate Cancer: The ORIOLE Phase 2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol, 2020. 6: 650. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32215577/

73. Battaglia, A., et al. Novel Insights into the Management of Oligometastatic Prostate Cancer: A Comprehensive Review. Eur Urol Oncol, 2019. 2: 174. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31017094/

74. Connor, M.J., et al. Targeting Oligometastasis with Stereotactic Ablative Radiation Therapy or Surgery in Metastatic Hormone-sensitive Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review of Prospective Clinical Trials. Eur Urol Oncol, 2020. 3: 582. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32891600/

75. Eisenhauer, E.A., et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer, 2009. 45: 228. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19097774/

76. U.S. Food & Drug Adminstration. FDA approves liquid biopsy NGS companion diagnostic test for multiple cancers and biomarkers. [Access date March 2022]. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-liquid-biopsy-ngscompanion-diagnostic-test-multiple-cancers-and-biomarkers

77. Lotan, T.L., et al. Report From the International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Consultation Conference on Molecular Pathology of Urogenital Cancers. I. Molecular Biomarkers in Prostate Cancer. Am J Surg Pathol, 2020. 44: e15. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32044806/

78. Hussain, M., et al. LBA12_PRPROfound: Phase III study of olaparib versus enzalutamide or abiraterone for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) with homologous recombination repair (HRR) gene alterations. Ann Oncol, 2019. 30. https://www.annalsofoncology.org/article/S0923-7534(19)60399-6/pdf

79. de Bono, J., et al. Olaparib for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med, 2020. 382: 2091. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32343890/

80. Hussain, M., et al. Survival with Olaparib in Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med, 2020. 383: 2345. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32955174/

81. European Medicines Agency. Pembrolizumab (KEYTRUDA). 2016. [Access date March 2022]. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/keytruda

82. Le, D.T., et al. PD-1 Blockade in Tumors with Mismatch-Repair Deficiency. N Engl J Med, 2015. 372: 2509. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26028255/

83. de Wit, R., et al. Cabazitaxel versus Abiraterone or Enzalutamide in Metastatic Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med, 2019. 381: 2506. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31566937/

84. Loriot, Y., et al. Prior long response to androgen deprivation predicts response to next-generation androgen receptor axis targeted drugs in castration resistant prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer, 2015. 51: 1946. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26208462/

85. Smith, M.R., et al. Natural history of rising serum prostate-specific antigen in men with castrate nonmetastatic prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol, 2005. 23: 2918. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15860850/

86. Smith, M.R., et al. Disease and host characteristics as predictors of time to first bone metastasis and death in men with progressive castration-resistant nonmetastatic prostate cancer. Cancer, 2011. 117: 2077. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21523719/

87. Crawford, E.D., et al. Challenges and recommendations for early identification of metastatic disease in prostate cancer. Urology, 2014. 83: 664. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24411213/

88. Fendler, W.P., et al. Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen Ligand Positron Emission Tomography in Men with Nonmetastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Clin Cancer Res, 2019. 25: 7448. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31511295/

89. Ryan, C.J., et al. Abiraterone acetate plus prednisone versus placebo plus prednisone in chemotherapy-naive men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (COU-AA-302): final overall survival analysis of a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol, 2015. 16: 152. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25601341/

90. Roviello, G., et al. Targeting the androgenic pathway in elderly patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer: A meta-analysis of randomized trials. Medicine (Baltimore), 2016. 95: e4636. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27787354/

91. Graff, J.N., et al. Efficacy and safety of enzalutamide in patients 75 years or older with chemotherapy-naive metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: results from PREVAIL. Ann Oncol, 2016. 27: 286. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26578735/

92. Evans, C.P., et al. The PREVAIL Study: Primary Outcomes by Site and Extent of Baseline Disease for Enzalutamide-treated Men with Chemotherapy-naive Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol, 2016. 70: 675. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27006332/

93. Shore, N.D., et al. Efficacy and safety of enzalutamide versus bicalutamide for patients with metastatic prostate cancer (TERRAIN): a randomised, double-blind, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol, 2016. 17: 153. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26774508/

94. Beer, T.M., et al. Enzalutamide in Men with Chemotherapy-naive Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer: Extended Analysis of the Phase 3 PREVAIL Study. Eur Urol, 2017. 71: 151. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27477525/

95. Tannock, I.F., et al. Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer. N Engl J Med, 2004. 351: 1502. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15470213/

96. Scher, H.I., et al. Trial Design and Objectives for Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer: Updated Recommendations From the Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Working Group 3. J Clin Oncol, 2016. 34: 1402. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26903579/

97. Kellokumpu-Lehtinen, P.L., et al. 2-Weekly versus 3-weekly docetaxel to treat castration-resistant advanced prostate cancer: a randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol, 2013. 14: 117. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23294853/

98. Serafini, A.N. Current status of systemic intravenous radiopharmaceuticals for the treatment of painful metastatic bone disease. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 1994. 30: 1187. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7525518/

99. Ballinger, J.R. Theranostic radiopharmaceuticals: established agents in current use. Br J Radiol, 2018. 91: 20170969. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29474096/

100. Sartor, O., et al. Lutetium-177-PSMA-617 for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med, 2021. 385: 1091. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34161051/

101. Hager, S., et al. Anti-tumour activity of platinum compounds in advanced prostate cancer-a systematic literature review. Ann Oncol, 2016. 27: 975. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27052650/

102. Mota, J.M., et al. Platinum-Based Chemotherapy in Metastatic Prostate Cancer With DNA Repair Gene Alterations. JCO Precis Oncol, 2020. 4: 355. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32856010/

103. Cereceda, L.E., et al. Management of vertebral metastases in prostate cancer: a retrospective analysis in 119 patients. Clin Prostate Cancer, 2003. 2: 34. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15046682/

104. Smith, M.R., et al. Denosumab and bone-metastasis-free survival in men with castration-resistant prostate cancer: results of a phase 3, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet, 2012. 379: 39. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22093187/

105. Marco, R.A., et al. Functional and oncological outcome of acetabular reconstruction for the treatment of metastatic disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2000. 82: 642. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10819275/

106. Stopeck, A.T., et al. Safety of long-term denosumab therapy: results from the open label extension phase of two phase 3 studies in patients with metastatic breast and prostate cancer. Support Care Cancer, 2016. 24: 447. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26335402/

107. Stopeck, A.T., et al. Denosumab compared with zoledronic acid for the treatment of bone metastases in patients with advanced breast cancer: a randomized, double-blind study. J Clin Oncol, 2010. 28: 5132. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21060033/

108. Body, J.J., et al. Hypocalcaemia in patients with metastatic bone disease treated with denosumab. Eur J Cancer, 2015. 51: 1812. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26093811/

Author Correspondence:

Prof. Dr. Semir A. Salim. Al Samarrai

Medical Director of Professor Al Samarrai Medical Center.

Dubai Healthcare City, Al-Razi Building 64, Block D, 2nd Floor, Suite 2018

E-mail: semiralsamarrai@hotmail.com

Tel: +97144233669