MALE INFERTILITY

Epidemiology, aetiology, pathophysiology, and risk factors

Comprehensive Review Article

Part 1

Prof. Dr. Semir. A. Salim. Al Samarrai

Definition and classification:

Infertility is defined by the inability of a sexually active, non-contraceptive couple to achieve spontaneous pregnancy within 1 year [1]. Primary infertility refers to couples that have never had a child and cannot achieve pregnancy after at least 12 consecutive months having sex without using birth control methods. Secondary infertility refers to infertile couples who have been able to achieve pregnancy at least once before (with the same or different sexual partner). Recurrent pregnancy loss is distinct from infertility and is defined as two or more failed pregnancies [2,3].

Epidemiology/aetiology/pathophysiology/risk factors:

- Introduction

About 15% of couples do not achieve pregnancy within 1 year and seek medical treatment for infertility. One in eight couples encounter problems when attempting to conceive a first child and one in six when attempting to conceive a subsequent child [4]. In 50% of involuntarily childless couples, a male-infertility-associated factor is found, usually together with abnormal semen parameters [1]. For this reason, all male patients belonging to infertile couples should undergo medical evaluation by a urologist trained in male reproduction. Male fertility can be impaired as a result of [1]:

• congenital or acquired urogenital abnormalities.

• gonadotoxic exposure (e.g., radiotherapy or chemotherapy).

• malignancies.

• urogenital tract infections.

• increased scrotal temperature (e.g., as a consequence of varicocele).

• endocrine disturbances.

• genetic abnormalities.

• immunological factors.

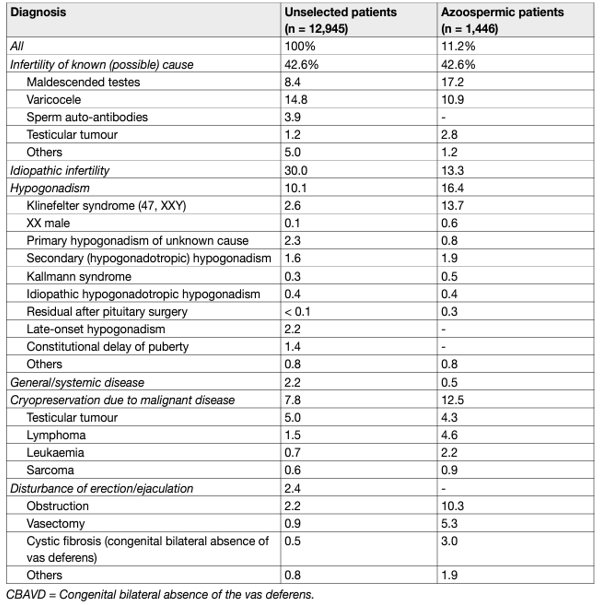

In 30-40% of cases, no male-associated factor is found to explain impairment of sperm parameters and historically was referred to as idiopathic male infertility. These men present with no previous history of diseases affecting fertility and have normal findings on physical examination and endocrine, genetic and biochemical laboratory testing, although semen analysis may reveal pathological findings. Unexplained male infertility is defined as infertility of unknown origin with normal sperm parameters and partner evaluation. Between 20 and 30% of couples will have unexplained infertility. It is now believed that idiopathic male infertility may be associated with several previously unidentified pathological factors, which include but are not limited to endocrine disruption as a result of environmental pollution, generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS)/sperm DNA damage, or genetic and epigenetic abnormalities [5]. Advanced paternal age has emerged as one of the main risk factors associated with the progressive increase in the prevalence of male factor infertility [6–13]. Likewise, advanced maternal age must be considered over the management of every infertile couple, and the consequent decisions in the diagnostic and therapeutic strategy of the male partner [14,15]. This should include the age and ovarian reserve of the female partner, since these parameters might determine decision-making in terms of timing and therapeutic strategies (e.g., assisted reproductive technology [ART] vs. surgical intervention) [6–9]. Table 1 summarises the main male-infertility-associated factors.

Table 1: Male infertility causes and associated factors and percentage of distribution in 10,469 patients

Diagnostic work-up:

Focused evaluation of male patients must always be undertaken and should include: a medical and reproductive history; physical examination; semen analysis – with strict adherence to World Health Organization (WHO) reference values for human semen characteristics [17], and hormonal evaluation. Other investigations (e.g., genetic analysis and imaging) may be required depending on the clinical features and semen parameters.

Medical/reproductive history and physical examination:

- Medical and reproductive history

Medical history should evaluate any risk factors and behavioural patterns that could affect the male partner’s fertility, such as lifestyle, family history (including, testicular cancer), comorbidity (including systemic diseases; e.g., hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obesity, MetS, testicular cancer, etc.), genito-urinary infections (including sexually transmitted infections), history of testicular surgery and exclude any potential known gonadotoxins [18]. Typical findings from the history of a patient with infertility include:

• cryptorchidism (uni- or bilateral).

• testicular torsion and trauma.

• genitourinary infections.

• exposure to environmental toxins.

• gonadotoxic medications (anabolic drugs, chemotherapeutic agents, etc.).

• exposure to radiation or cytotoxic agents.

- Physical examination

Physical examination Focused physical examination is compulsory in the evaluation of every infertile male, including presence of secondary sexual characteristics. The size, texture and consistency of the testes must be evaluated. In clinical practice, testicular volume is assessed by Prader’s orchidometer [19]; orchidometry may overestimate testicular volume when compared with US assessment [20]. There are no uniform reference values in terms of Prader’s orchidometer-derived testicular volume, due to differences in the populations studied (e.g., geographic area, nourishment, ethnicity and environmental factors) [19–21]. The mean Prader’s orchidometer-derived testis volume reported in the European general population is 20.0 ± 5.0 mL [19], whereas in infertile patients it is 18.0 ± 5.0 mL [19,22,23]. The presence of the vas deferens, fullness of epididymis and presence of a varicocele should be always determined. Likewise, palpable abnormalities of the testis, epididymis, and vas deferens should be evaluated. Other physical alterations, such as abnormalities of the penis (e.g., phimosis, short frenulum, fibrotic nodules, epispadias, hypospadias, etc.), abnormal body hair distribution and gynecomastia, should also be evaluated. Typical findings from the physical examination of a patient with characteristics suggestive for testicular deficiency include:

• abnormal secondary sexual characteristics.

• abnormal testicular volume and/or consistency.

• testicular masses (potentially suggestive of cancer).

• absence of testes (uni-bilaterally).

• gynaecomastia.

• varicocele.

- Semen analysis

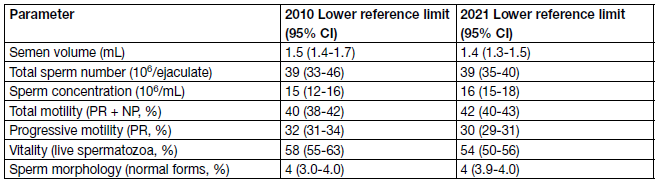

A comprehensive andrological examination is always indicated in every infertile couple, both if semen analysis shows abnormalities, and even in the case of normal sperm parameters as compared with reference values [24]. Important treatment decisions are based on the results of semen analysis and most studies evaluate semen parameters as a surrogate outcome for male fertility. However, semen analysis cannot precisely distinguish fertile from infertile men [25]; therefore, it is essential that the complete laboratory work-up is standardised according to reference values (Table 2).

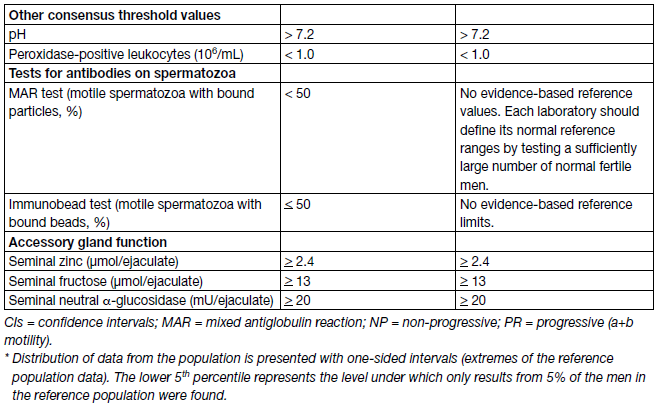

Table 2: Lower reference limits (5th centiles and their 95% CIs) for semen characteristics

There is consensus that modern semen analysis must follow these guidelines. Ejaculate analysis has been standardised by the WHO and disseminated by publication of the most updated version of the WHO Laboratory Manual for the Examination and Processing of Human Semen. Of note, the 6th edition the WHO Manual for the Examination and Processing of Human Semen [26] has been published on July 2021 and reports some differences compared to the previous edition (5th edn.) [27] that has been used throughout the last eleven years. Therefore, it is possible that the worldwide implementation in the everyday clinical practice of the newly-released version could be gradual.

Overall, the procedures for semen examination are divided into three chapters:

• Basic examinations, which contains fewer investigations than the previous edition that should be performed by every laboratory, based on step-wise procedures and evidence-based techniques.

• Extended analyses, which are performed by choice of the laboratory or by special request from the clinicians.

• Advanced examinations, that are classified as focused on very specialized as well as mainly research methods and other emerging technologies. Overall, a few relevant differences have been identified between 6th and 5th editions.

Basic examination:

- Assessment of sperm numbers: the laboratory should not stop assessing the number of sperm at low concentrations (2 million/mL), as suggested in the 5th edition, but report lower concentrations, noting that the errors associated with counting a small number of spermatozoa may be very high. In this edition, it is recognised that the total sperm numbers per ejaculate (sperm output) have more diagnostic value than sperm concentration; therefore, semen volume must be measured accurately.

- Assessment of sperm motility: the categorisation of sperm motility has reverted back to fast progressively motile, slow progressively motile, non-progressively motile and immotile (grade a, b, c or d) because presence (or absence) of rapid progressive spermatozoa is recognised to be clinically important.

• Assessment of sperm morphology: the 6th edition has recommended the Tygerberg strict criteria by sperm adapted Papanicolaou staining. Moreover, vitality test should not be performed in all samples and only if few motile sperm are found.

- Extended examinations: contain procedures to detect leukocytes and markers of genital tract inflammation, sperm antibodies, indices of multiple sperm defects, sequence of ejaculation, methods to detect sperm aneuploidy, semen biochemistry and sperm DNA fragmentation.

Research tests include assessment of ROS and oxidative stress, membrane ion channels, acrosome reaction and sperm chromatin structure and stability, computer assisted sperm analysis (CASA).

In the latest edition of the WHO Manual, the data presented in the 5th edition have been further evaluated and complemented with data from around 3,500 men in 12 countries [24]. Of note, the distributions do not differ much from the compilation of 2010. Table 41 reports the lower reference limits for semen characteristics according to the 2010 and 2021 version of the WHO Manual. According to the new WHO Manual, the lower fifth percentile of data from men in the reference population (Table 2) does not represent a limit between fertile and infertile men. For a general prediction of live birth in vivo as well as in vitro, a multiparametric interpretation of the entire men’s and partner’s reproductive potential are needed. It has also become clear from studies that more complex testing than semen analysis may be required in everyday clinical practice, particularly in men belonging to couples with recurrent pregnancy loss from natural conception or ART and men with unexplained male infertility. Although definitive conclusions cannot be drawn, given the heterogeneity of the studies, in these patients there is evidence that sperm DNA may be damaged, thus resulting in pregnancy failure [5,28,29].

If semen analysis is normal according to WHO criteria, a single test is sufficient. If the results are abnormal on at least two tests, further andrological investigation is indicated. According to WHO reference criteria 5th end, it is important to differentiate between the following [27]:

• oligozoospermia: < 15 million spermatozoa/Ml.

• asthenozoospermia: < 32% progressive motile spermatozoa.

• teratozoospermia: < 4% normal forms.

None of the individual sperm parameters (e.g., concentration, morphology and motility), are diagnostic per se of infertility. Often, all three anomalies occur simultaneously, which is defined as oligo-astheno-terato-zoospermia (OAT) syndrome. As in azoospermia (namely, the complete absence of spermatozoa in semen), in severe cases of oligozoospermia (spermatozoa < 5 million/mL) [30], there is an increased incidence of obstruction of the male genital tract and genetic abnormalities. In those cases, a more comprehensive assessment of the hormonal profile may be helpful to further and more accurately differentially diagnose among pathological conditions. In azoospermia, the semen analysis may present with normal ejaculate volume and azoospermia after centrifugation. A recommended method is semen centrifugation at 3,000 g for 15 minutes and a thorough microscopic examination by phase contrast optics at ×200 magnification of the pellet. All samples can be stained and re-examined microscopically [26]. This is to ensure that small quantities of sperm are detected, which may be potentially used for intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI); therefore, removing the need for surgical intervention.

The measurement of sperm DNA Fragmentation Index (DFI) is an important measure in the diagnostic evaluation of infertility:

Semen analysis is a descriptive evaluation and may be unable to discriminate between the sperm of fertile and infertile men. Therefore, it is now apparent that sperm DNA damage may occur in men with infertility. DNA fragmentation, or the accumulation of single- and double-strand DNA breaks, is a common property of sperm, and an increase in the level of sperm DNA fragmentation has been shown to reduce the chances of natural conception. Although no studies have unequivocally and directly tested the impact of sperm DNA damage on clinical management of infertile couples, sperm DNA damage is more common in infertile men and has been identified as a major contributor to male infertility, as well as poorer outcomes following ART [31,32], including impaired embryo development [31], miscarriage, recurrent pregnancy loss [28,29,33], and birth defects [31]. Sperm DNA damage can be increased by several factors including hormonal anomalies, varicocele, chronic infection and lifestyle factors (e.g., smoking) [32].

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate nick end labelling (TUNEL) and the alkaline comet test (COMET) directly measure DNA damage. Conversely, sperm chromatin structure assay (SCSA) and sperm chromatic dispersion test (SCD) are indirect tools for DNA fragmentation assessment. Sperm chromatin structure assay is still the most widely studied and one of the most commonly used techniques to detect DNA damage [34,35]. In SCSA, the number of cells with DNA damage is indicated by the DNA fragmentation index (DFI) [36], whereas the proportion of immature sperm with defects in the histone-toprotamine transition is indicated by high DNA stainability [37]. It is suggested that a threshold DFI of 25% as measured with SCSA, is associated with reduced pregnancy rates via natural conception or intra-uterine insemination (IUI) [35]. Furthermore, DFI values > 50% on SCSA are associated with poorer outcomes from in vitro fertilisation (IVF). More recently, the mean COMET score and scores for proportions of sperm with high or low DNA damage have been shown to be of value in diagnosing male infertility and providing additional discriminatory information for the prediction of both IVF and ICSI live births [32]. Testicular sperm is reported to have lower levels of sperm DFI when compared to ejaculated sperm [38]. Couples with elevated DNA fragmentation may benefit from combination of testicular sperm extraction (TESE) and ICSI, an approach called TESE-ICSI, which may not overcome infertility when applied to an unselected population of infertile men with untested DFI values [35,38]. However, further evidence is needed to support this practice in the routine clinical setting [38].

The hormonal determinations are as well very important measure in the diagnostic evaluation of male infertility:

In men with testicular deficiency, hypergonadotropic hypogonadism (also called primary hypogonadism) is usually present, with high levels of FSH and LH, with or without low levels of testosterone. Generally, the levels of FSH negatively correlate with the number of spermatogonia [39]. When spermatogonia are absent or markedly diminished, FSH level is usually elevated; when the number of spermatogonia is normal, but maturation arrest exists at the spermatocyte or spermatid level, FSH level is usually within the normal range [39]. However, for patients undergoing TESE, FSH levels do not accurately predict the presence of spermatogenesis, as men with maturation arrest on histology can have both normal FSH and testicular volume [40,41]. Furthermore, men with non-obstructive azoospermia (NOA) and high levels of FSH may still harbour focal areas of spermatogenesis at the time of TESE or microdissection TESE (mTESE) [41,42].

The genetic testing is also so important measure in the diagnostic evaluation of male infertility:

All urologists working in andrology must have an understanding of the genetic abnormalities most commonly associated with infertility, so that they can provide correct advice to couples seeking fertility treatment. Men with low sperm counts can still be offered a reasonable chance of paternity, using IVF, ICSI and sperm extraction from the testes in cases of azoospermia. However, the spermatozoa of infertile men show an increased rate of aneuploidy, structural chromosomal abnormalities, and DNA damage, carrying the risk of passing genetic abnormalities to the next generation. Current routine clinical practice is based on the screening of genomic DNA from peripheral blood samples. However, screening of chromosomal anomalies in spermatozoa (sperm aneuploidy) is also feasible and can be performed in selected cases (e.g., recurrent miscarriage) [43–45].

Chromosomal abnormalities:

can be numerical (e.g., trisomy) or structural (e.g., inversions or translocations). In a survey of pooled data from 11 publications, including 9,766 infertile men, the incidence of chromosomal abnormalities was 5.8% [46]. Of these, sex chromosome abnormalities accounted for 4.2% and autosomal abnormalities for 1.5%. In comparison, the incidence of abnormalities was 0.38% in pooled data from three series, with a total of 94,465 new-born male infants, of whom 131 (0.14%) had sex chromosomal abnormalities and 232 (0.25%) autosomal abnormalities [46]. The frequency of chromosomal abnormalities increases as testicular deficiency becomes more severe. Patients with sperm count < 5 million/mL already show a 10-fold higher incidence (4%) of mainly autosomal structural abnormalities compared with the general population [47,48]. Men with NOA are at highest risk, especially for sex chromosomal anomalies (e.g., Klinefelter syndrome) [49,50]. Based on the frequencies of chromosomal aberrations in patients with different sperm concentration, karyotype analysis is currently indicated in men with azoospermia or oligozoospermia (spermatozoa < 10 million/mL) [48]. This broad selection criterion has been recently externally validated, with the finding that the suggested threshold has a low sensitivity, specificity, and discrimination (80%, 37%, and 59%, respectively) [51].

In this context, a novel nomogram, with a 2% probability cut-off, which allows for a more careful detection of karyotype alterations has been developed [51]. Notwithstanding, the clinical value of spermatozoa < 10 million/mL remains a valid threshold until further studies, evaluating the cost-effectiveness, in which costs of adverse events due to chromosomal abnormalities (e.g., miscarriages and children with congenital anomalies) are performed [52]. If there is a family history of recurrent spontaneous abortions, malformations or mental retardation, karyotype analysis should be requested, regardless of the sperm concentration.

Klinefelter syndrome is the most common sex chromosomal abnormality [53]. Adult men with Klinefelter syndrome usually have small firm testes along with features of primary hypogonadism. The phenotype is the final result of a combination between genetic, hormonal and age-related factors [54]. The phenotype varies from that of a normally virilised male to one with the stigmata of androgen deficiency. In most cases infertility and reduced testicular volume are the only clinical features that can be detected. Leydig cell function is also commonly impaired in men with Klinefelter syndrome and thus testosterone deficiency is more frequently observed than in the general population [55], although rarely observed during the peri-pubertal period, which usually occurs in a normal manner [54,56]. Rarely, more pronounced signs and symptoms of hypogonadism can be present, along with congenital abnormalities including heart and renal problems [57]. The presence of germ cells and sperm production are variable in men with Klinefelter syndrome and are more frequently observed in mosaicism, 46,XY/47,XXY. Based on sperm fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) studies showing an increased frequency of sex chromosomal abnormalities and increased incidence of autosomal aneuploidy (disomy for chromosomes 13, 18 and 21), concerns have been raised about the chromosomal normality of the embryos generated through ICSI [58]. The production of 24,XY sperm has been reported in 0.9% and 7.0% of men with Klinefelter mosaicism [59,60] and in 1.36-25% of men with somatic karyotype 47,XXY [61–64]. In patients with azoospermia, TESE or mTESE are therapeutic options as spermatozoa can be recovered in up to 50% of cases [65,66]. Although the data are not unique [66], there is growing evidence that TESE or mTESE yields higher sperm recovery rates when performed at a younger age [67,68]. Numerous healthy children have been born using ICSI without pre-implantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) although the conception of one 47,XXY foetus has been reported [53]. Although data published so far have not reported any difference in the prevalence of aneuploidy in children conceived using ICSI in Klinefelter syndrome compared to the general population, men with Klinefelter syndrome undergoing fertility treatments should be counselled regarding the potential genetic abnormalities in their offspring. Regular medical follow-up of men with Klinefelter syndrome is recommended as testosterone therapy may be considered if testosterone levels are in the hypogonadal range when fertility issues have been addressed [69]. Since this syndrome is associated with several general health problems, appropriate medical follow-up is therefore advised [70,71,72]. In particular, men with Klinefelter syndrome are at higher risk of metabolic and cardiovasculardiseases (CVD), including venous thromboembolism (VTE). Therefore, men with Klinefelter syndrome should be made aware of this risk, particularly when starting testosterone therapy [73]. In addition, a higher risk of haematological malignancies has been reported in men with Klinefelter syndrome [70]. Testicular sperm extraction in peri-pubertal or pre-pubertal boys with Klinefelter syndrome aiming at cryopreservation of testicular spermatogonial stem cells is still considered experimental and should only be performed within a research setting [74]. The same applies to sperm retrieval in older boys who have not considered their fertility potential [75].

Autosomal karyotype:

Genetic counselling should be offered to all couples seeking fertility treatment (including IVF/ICSI) when the male partner has an autosomal karyotype abnormality. The most common autosomal karyotype abnormalities are Robertsonian translocations, reciprocal translocations, paracentric inversions, and marker chromosomes. It is important to look for these structural chromosomal anomalies because there is an increased associated risk of aneuploidy or unbalanced chromosomal complements in the foetus. As with Klinefelter syndrome, sperm FISH analysis provides a more accurate risk estimation of affected offspring. However, the use of this genetic test is largely limited by the availability of laboratories able to perform this analysis [76]. When IVF/ICSI is carried out for men with translocations, PGD or amniocentesis should be performed [77,78].

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is an autosomal-recessive disorder [79]. It is the most common genetic disease of Caucasians; 4% are carriers of gene mutations involving the CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene located on chromosome 7p. It encodes a membrane protein that functions as an ion channel and influences the formation of the ejaculatory duct, seminal vesicle, vas deferens and distal two-thirds of the epididymis. Approximately 2,000 CFTR mutations have been identified and any CFTR alteration may lead to congenital bilateral absence of the vas deferens (CBAVD).

Clinical diagnosis of absent vasa is easy to miss and all men with azoospermia should be carefully examined to exclude CBAVD, particularly those with a semen volume < 1.0 mL and acidic pH < 7.0 [80–82]. In patients with CBAVD-only or CF, TESA, microsurgical epididymal sperm aspiration (MESA) or TESE with ICSI can be used to achieve pregnancy. However, higher sperm quality, easier sperm retrieval and better ICSI outcomes are associated with CBAVD-only patients compared with CF patients [83].

Y Microdeletions-Partial and Complete:

Microdeletions on the Y-chromosome are termed AZFa, AZFb and AZFc deletions [84]. Clinically relevant deletions remove partially, or in most cases completely, one or more of the AZF regions, and are the most frequent molecular genetic cause of severe oligozoospermia and azoospermia [85]. In each AZF region, there are several spermatogenesis candidate genes [86]. Deletions occur en bloc (i.e., removing more than one gene), it is not possible to determine the role of a single AZF gene from the AZF deletion phenotype and it is unclear if they all participate in spermatogenesis.

Clinical implications of Y microdeletions:

The clinical significance of Yq microdeletions can be summarised as follows:

• They are not found in normozoospermic men, proving there is a clear-cut cause-and-effect relationship between Y-deletions and spermatogenic failure [87].

• The highest frequency of Y-deletions is found in azoospermic men (8-12%), followed by oligozoospermic (3-7%) men [88,89].

The clinical significance of Yq microdeletions can be summarised as follows:

• They are not found in normozoospermic men, proving there is a clear-cut cause-and-effect relationship between Y-deletions and spermatogenic failure [87].

• The highest frequency of Y-deletions is found in azoospermic men (8-12%), followed by oligozoospermic (3-7%) men [88,89].

• Deletions are extremely rare with a sperm concentration > 5 million/mL (~0.7%) [90].

• AZFc deletions are most common (65-70%), followed by Y-deletions of the AZFb and AZFb+c or AZFa+b+c regions (25-30%). AZFa region deletions are rare (5%) [91]. • Complete deletion of the AZFa region is associated with severe testicular phenotype (Sertoli cell only syndrome), while complete deletions of the AZFb region is associated with spermatogenic arrest. Complete deletions that include the AZFa and AZFb regions are of poor prognostic significance for retrieving sperm at the time of TESE and sperm is not found in these patients. Therefore, TESE should not be attempted in these patients [92,93].

• Deletions of the AZFc region causes a variable phenotype ranging from azoospermia to oligozoospermia.

• Sperm can be found in 50-75% of men with AZFc microdeletions [92–94].

• Men with AZFc microdeletions who are oligo-zoospermic or in whom sperm is found at the time of TESE must be counselled that any male offspring will inherit the deletion.

• Classical (complete) AZF deletions do not confer a risk for cryptorchidism or testicular cancer [90,95].

Testing for Y Microdeletions:

Historically, indications for AZF deletion screening are based on sperm count and include azoospermia and severe oligozoospermia (spermatozoa count < 5 million/mL). A recent meta-analysis assessing the prevalence of microdeletions on the Y chromosome in oligo-zoospermic men in 37 European and North American studies (n = 12,492 oligo-zoospermic men) showed that the majority of microdeletions occurred in men with sperm concentrations < 1 million sperm/mL, with < 1% identified in men with > 1 million sperm/mL [90]. In this context, while an absolute threshold for clinical testing cannot be universally given, patients may be offered testing if sperm counts are < 5 million sperm/mL, but must be tested if <1 million sperm/mL. With the efforts of the European Academy of Andrology (EAA) guidelines and the European Molecular Genetics Quality Network external quality control programme (http://www.emqn.org/emqn/), Yq testing has become more reliable in different routine genetic laboratories. The EAA guidelines provide a set of primers capable of detecting > 95% of clinically relevant deletions [96].

Genetic counselling of AZF deletions:

After conception, any Y-deletions are transmitted to the male offspring, and genetic counselling is therefore mandatory. In most cases, father and son will have the same microdeletion [96], but occasionally the son may have a more extensive deletion [97]. The extent of spermatogenic failure (still in the range of azoo-/ oligo-zoospermia) cannot be predicted entirely in the sun, due to the different genetic background and the presence or absence of environmental factors with potential toxicity on reproductive function. A significant proportion of spermatozoa from men with complete AZFc deletion are nullisomic for sex chromosomes [98,99], indicating a potential risk for any offspring to develop 45, X0 Turner’s syndrome and other phenotypic anomalies associated with sex chromosome mosaicism, including ambiguous genitalia [100]. Despite this theoretical risk, babies born from fathers affected by Yq microdeletions are phenotypically normal [95,96]. This could be due to the reduced implantation rate and a likely higher risk of spontaneous abortion of embryos bearing a 45, X0 karyotype.

Autosomal defects with severe phenotypic abnormalities and infertility:

Several inherited disorders are associated with severe or considerable generalised abnormalities and infertility (e.g., Prader-Willi syndrome [101], Bardet-Biedl syndrome [102] Noonan’s syndrome, Myotonic dystrophy, dominant polycystic kidney disease [103,104], and 5 α-reductase deficiency [105–108], etc.) Preimplantation genetic screening may be necessary in order to improve the ART outcomes among men with autosomal chromosomal defects [109,110].

Sperm chromosomal abnormalities:

Sperm can be examined for their chromosomal constitution using FISH both in men with normal karyotype and with anomalies. Aneuploidy in sperm, particularly sex chromosome aneuploidy, is associated with severe damage to spermatogenesis [46,111–113] and with translocations and may lead to recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL) or recurrent implantation failure [114]. In a large retrospective series, couples with normal sperm FISH had similar outcomes from IVF and ICSI on pre-implantation genetic screening (PGS). However, couples with abnormal FISH had better clinical outcomes after PGS, suggesting a potential contribution of sperm to aneuploidic abnormalities in the embryo [115]. In men with sperm aneuploidy, PGS combined with IVF and ICSI can increase chances of live births [45].

Measurement of Oxidative Stress:

Oxidative stress is considered to be central in male infertility by affecting sperm quality, function, as well as the integrity of sperm [116]. Oxidative stress may lead to sperm DNA damage and poorer DNA integrity, which are associated with poor embryo development, miscarriage and infertility [117,118]. Spermatozoa are vulnerable to oxidative stress and have limited capacity to repair damaged DNA. Oxidative stress is generally associated with poor lifestyle (e.g., smoking) and environmental exposure, and therefore antioxidant regimens and lifestyle interventions may reduce the risk of DNA fragmentation and improve sperm quality [119]. However, these data have not been supported by RCTs. Furthermore, there are no standardised testing methods for ROS and the duration of antioxidant treatments. Although ROS can be measured by various assays (e.g., chemiluminescence), routine measurement of ROS testing should remain experimental until these tests are validated in RCTs [120].

Outcomes from assisted reproductive technology and long-term health implications to the male and Offspring:

It is estimated that > 4 million babies have been born with ART since the first baby was conceived by IVF in 1978 [121]. As the number of couples undergoing ART has increased [122,123], safety concerns related to ART have been raised. Assisted reproductive technology-conceived offspring have poorer prenatal outcomes, such as lower birth weight, lower gestational age, premature delivery, and higher hospital admissions compared with naturally conceived offspring [124,125]. However, the exact mechanisms resulting in these complications remain obscure. Birth defects have also been associated with children conceived via ART [126–128]. Meta-analyses have shown a 30-40% increase in major malformations linked with ART [129-131]. However, debate continues as to whether the increased risk of birth defects is related to parental age, ART or the intrinsic defects in spermatogenesis in infertile men [132-137].

The imaging in infertile men is an important measure in the diagnostic evaluation of infertility.

In addition to physical examination, a scrotal US may be helpful in: (i) measuring testicular volume; (ii) assessing testicular anatomy and structure in terms of US patterns, thus detecting signs of testicular dysgenesis often related to impaired spermatogenesis (e.g., non-homogeneous testicular architecture and microcalcifications) and testicular tumours; and, (iii) finding indirect signs of obstruction (e.g., dilatation of rete testis, enlarged epididymis with cystic lesions, or absent vas deferens) [20].

Scrotal US:

Scrotal US is widely used in everyday clinical practice in patients with oligo-zoospermia or azoospermia, as infertility has been found to be an additional risk factor for testicular cancer [138,139]. It can be used in the diagnosis of several diseases causing infertility including testicular neoplasms and varicocele.

In one study, men with infertility had an increased risk of testicular cancer (hazard ratio [HR] 3.3). When infertility was refined according to individual semen parameters, oligo-zoospermic men had an increased risk of cancer compared with fertile control subjects (HR 11.9) [140]. In a recent systematic review infertile men with testicular microcalcification (TM) were found to have a ~18-fold higher prevalence of testicular cancer [141]. However, the utility of US as a routine screening tool in men with infertility to detect testicular cancer remains a matter of debate [138, 139].

Small hypoechoic/hyperechoic areas may be diagnosed as intra-testicular cysts, focal Leydig cell hyperplasia, fibrosis and focal testicular inhomogeneity after previous pathological conditions. Hence, they require careful periodic US assessment and follow-up, especially if additional risk factors for malignancy are present (i.e., infertility, bilateral TM, history of cryptorchidism, testicular atrophy, inhomogeneous parenchyma, history of testicular tumour, history of/contralateral tumour)

In summary, if an indeterminate lesion is detected incidentally on US in an infertile man, MDT discussion is highly recommended. Based upon the current literature, lesions < 5mm in size are likely to be benign and serial US and self-examination can be performed. However, men with larger sized lesions (> 5mm), which are hypoechoic or demonstrate vascularity, may be considered for open US-guided testicular biopsy, testis sparing surgery with tumour enucleation for frozen section examination or radical orchidectomy. Therefore, in making a definitive treatment decision for surveillance vs. intervention, consideration should be given to the size of the lesion, echogenicity, vascularity and previous history (e.g., cryptorchidism, previous history of germ cell tumour [GCT]). If intervention is to be undertaken in men with severe hypo spermatogenesis (e.g., azoospermia), then a simultaneous TESE can be undertaken, along with sperm banking.

REFERENCES:

- WHO, WHO Manual for the Standardized Investigation and Diagnosis of the Infertile Couple. 2000, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

- Bender Atik, R., et al. ESHRE guideline: recurrent pregnancy loss. Hum Reprod Open, 2018. 2018: hoy004.

- Zegers-Hochschild, F., et al. The International Glossary on Infertility and Fertility Care, 2017. Fertil Steril, 2017. 108: 393.

- Greenhall, E., et al. The prevalence of subfertility: a review of the current confusion and a report of two new studies. Fertil Steril, 1990. 54: 978.

- Agarwal, A., et al. Male Oxidative Stress Infertility (MOSI): Proposed Terminology and Clinical Practice Guidelines for Management of Idiopathic Male Infertility. World J Mens Health, 2019. 37: 296.

- Brandt, J.S., et al. Advanced paternal age, infertility, and reproductive risks: A review of the literature. Prenat Diagn, 2019. 39: 81.

- Avellino, G., et al. Common urologic diseases in older men and their treatment: how they impact fertility. Fertil Steril, 2017. 107: 305.

- Jennings, M.O., et al. Management and counseling of the male with advanced paternal age. Fertil Steril, 2017. 107: 324.

- Ramasamy, R., et al. Male biological clock: a critical analysis of advanced paternal age. Fertil Steril, 2015. 103: 1402.

- Starosta, A., et al. Predictive factors for intrauterine insemination outcomes: a review. Fertil Res Pract, 2020. 6: 23.

- Van Opstal, J., et al. Male age interferes with embryo growth in IVF treatment. Hum Reprod, 2020.

- Vaughan, D.A., et al. DNA fragmentation of sperm: a radical examination of the contribution of oxidative stress and age in 16 945 semen samples. Human Reprod, 2020. 35: 2188.

- du Fossé, N.A., et al. Advanced paternal age is associated with an increased risk of spontaneous miscarriage: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Human Reprod Update, 2020. 26: 650.

- Wennberg, A.L., et al. Effect of maternal age on maternal and neonatal outcomes after assisted reproductive technology. Fertil Steril, 2016. 106: 1142.

- Sunderam, S., et al. Comparing fertilization rates from intracytoplasmic sperm injection to conventional in vitro fertilization among women of advanced age with non-male factor infertility: a meta-analysis. Feril Steril, 2020. 113: 354.

- Andrology, In: Male reproductive health and dysfunction. Nieschlag E, Behre HM and Nieschlag S (eds). 2010, Springer Verlag: Berlin.

- Cooper, T.G., et al. World Health Organization reference values for human semen characteristics. Hum Reprod Update, 2010. 16: 231.

- Kasman, A.M., et al. Association between preconception paternal health and pregnancy loss in the USA: an analysis of US claims data. Hum Reprod, 2020.

- Nieschlag E, et al., Andrology: Male Reproductive Health and Dysfunction, 3rd edn. Anamnesis and physical examination, ed. Nieschlag E, Behre HM & Nieschlag S. 2010, Berlin.

- Lotti, F., et al. Ultrasound of the male genital tract in relation to male reproductive health. Hum Reprod Update, 2015. 21: 56.

- Bahk, J.Y., et al. Cut-off value of testes volume in young adults and correlation among testes volume, body mass index, hormonal level, and seminal profiles. Urology, 2010. 75: 1318.

- Jorgensen, N., et al. East-West gradient in semen quality in the Nordic-Baltic area: a study of men from the general population in Denmark, Norway, Estonia and Finland. Hum Reprod, 2002. 17: 2199.

- Jensen, T.K., et al. Association of in utero exposure to maternal smoking with reduced semen quality and testis size in adulthood: a cross-sectional study of 1,770 young men from the general population in five European countries. Am J Epidemiol, 2004. 159: 49.

- Campbell, M.J., et al. Distribution of semen examination results 2020 – A follow up of data collated for the WHO semen analysis manual 2010. Andrology, 2021. 9: 817.

- Boeri, L., et al. Normal sperm parameters per se do not reliably account for fertility: A case–control study in the real-life setting. Andrologia, 2020. n/a: e13861.

- WHO. WHO laboratory manual for the examination and processing of human semen Sixth edition. 2021.

- WHO, WHO Laboratory Manual for the Examination and Processing of Human Semen, in 5th edn. 2010.

- Yifu, P., et al. Sperm DNA fragmentation index with unexplained recurrent spontaneous abortion: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod, 2020: 101740.

- McQueen, D.B., et al. Sperm DNA fragmentation and recurrent pregnancy loss: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Fertil Steril, 2019. 112: 54.

- Grimes, D.A., et al. “Oligozoospermia,” “azoospermia,” and other semen-analysis terminology: the need for better science. Feril Steril, 2007. 88: 1491.

- Simon, L., et al. Sperm DNA Fragmentation: Consequences for Reproduction. Adv Exp Med Biol, 2019. 1166: 87.

- Nicopoullos, J., et al. Novel use of COMET parameters of sperm DNA damage may increase its utility to diagnose male infertility and predict live births following both IVF and ICSI. Hum Reprod, 2019.

- Tan, J., et al. Association between sperm DNA fragmentation and idiopathic recurrent pregnancy loss: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Biomed Online, 2019. 38: 951.

- Kim, G.Y. What should be done for men with sperm DNA fragmentation? Clin Exp Reprod Med, 2018. 45: 101.

- Evenson, D.P. Sperm chromatin structure assay (SCSA(R)). Methods Mol Biol, 2013. 927: 147.

- Evenson, D.P., et al. Sperm chromatin structure assay: its clinical use for detecting sperm DNA fragmentation in male infertility and comparisons with other techniques. J Androl, 2002. 23: 25.

- Tarozzi, N., et al. Clinical relevance of sperm DNA damage in assisted reproduction. Reprod Biomed Online, 2007. 14: 746.

- Esteves, S.C., et al. Reproductive outcomes of testicular versus ejaculated sperm for intracytoplasmic sperm injection among men with high levels of DNA fragmentation in semen: systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril, 2017. 108: 456.

- Martin-du-Pan, R.C., et al. Increased follicle stimulating hormone in infertile men. Is increased plasma FSH always due to damaged germinal epithelium? Hum Reprod, 1995. 10: 1940.

- Ishikawa, T., et al. Clinical and hormonal findings in testicular maturation arrest. BJU international, 2004. 94: 1314.

- Ramasamy, R., et al. High serum FSH levels in men with nonobstructive azoospermia does not affect success of microdissection testicular sperm extraction. Fertil Steril, 2009. 92: 590.

- Zeadna, A., et al. Prediction of sperm extraction in non-obstructive azoospermia patients: a machine-learning perspective. Hum Reprod, 2020. 35: 1505.

- Carrell, D.T. The clinical implementation of sperm chromosome aneuploidy testing: pitfalls and promises. J Androl, 2008. 29: 124.

- Aran, B., et al. Screening for abnormalities of chromosomes X, Y, and 18 and for diploidy in spermatozoa from infertile men participating in an in vitro fertilization-intracytoplasmic sperm injection program. Feril Steril, 1999. 72: 696.

- Kohn, T.P., et al. Genetic counseling for men with recurrent pregnancy loss or recurrent implantation failure due to abnormal sperm chromosomal aneuploidy. J Assist Reprod Genet, 2016. 33: 571.

- Johnson, M.D. Genetic risks of intracytoplasmic sperm injection in the treatment of male infertility: recommendations for genetic counseling and screening. Fertil Steril, 1998. 70: 397.

- Clementini, E., et al. Prevalence of chromosomal abnormalities in 2078 infertile couples referred for assisted reproductive techniques. Hum Reprod, 2005. 20: 437.

- Vincent, M.C., et al. Cytogenetic investigations of infertile men with low sperm counts: a 25-year experience. J Androl, 2002. 23: 18.

- Deebel, N.A., et al. Age-related presence of spermatogonia in patients with Klinefelter syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update, 2020. 26: 58.

- Vockel, M., et al. The X chromosome and male infertility. Hum Genet, 2019.

- Ventimiglia, E., et al. When to Perform Karyotype Analysis in Infertile Men? Validation of the European Association of Urology Guidelines with the Proposal of a New Predictive Model. Eur Urol, 2016. 70: 920.

- Dul, E.C., et al. The prevalence of chromosomal abnormalities in subgroups of infertile men. Hum Reprod, 2012. 27: 36.

- Davila Garza, S.A., et al. Reproductive outcomes in patients with male infertility because of Klinefelter’s syndrome, Kartagener’s syndrome, round-head sperm, dysplasia fibrous sheath, and ‘stump’ tail sperm: an updated literature review. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol, 2013. 25: 229.

- Bonomi, M., et al. Klinefelter syndrome (KS): genetics, clinical phenotype and hypogonadism. J Endocrinol Invest, 2017. 40: 123.

- Pozzi, E., et al. Rates of hypogonadism forms in Klinefelter patients undergoing testicular sperm extraction: A multicenter cross-sectional study. Andrology, 2020. 8: 1705.

- Wang, C., et al. Hormonal studies in Klinefelter’s syndrome. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf), 1975. 4: 399.

- Calogero, A.E., et al. Klinefelter syndrome: cardiovascular abnormalities and metabolic disorders. J Endocrinol Invest, 2017. 40: 705.

- Staessen, C., et al. PGD in 47,XXY Klinefelter’s syndrome patients. Hum Reprod Update, 2003. 9: 319.

- Chevret, E., et al. Increased incidence of hyperhaploid 24,XY spermatozoa detected by three-colour FISH in a 46,XY/47,XXY male. Hum Genet, 1996. 97: 171.

- Martini, E., et al. Constitution of semen samples from XYY and XXY males as analysed by in-situ hybridization. Hum Reprod, 1996. 11: 1638.

- Cozzi, J., et al. Achievement of meiosis in XXY germ cells: study of 543 sperm karyotypes from an XY/XXY mosaic patient. Hum Genet, 1994. 93: 32.

- Estop, A.M., et al. Meiotic products of a Klinefelter 47,XXY male as determined by sperm fluorescence in-situ hybridization analysis. Hum Reprod, 1998. 13: 124.

- Foresta, C., et al. High incidence of sperm sex chromosomes aneuploidies in two patients with Klinefelter’s syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 1998. 83: 203.

- Guttenbach, M., et al. Segregation of sex chromosomes into sperm nuclei in a man with 47,XXY Klinefelter’s karyotype: a FISH analysis. Hum Genet, 1997. 99: 474.

- Aksglaede, L., et al. Testicular function and fertility in men with Klinefelter syndrome: a review. Eur J Endocrinol, 2013. 168: R67.

- Corona, G., et al. Sperm recovery and ICSI outcomes in Klinefelter syndrome: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Hum Reprod Update, 2017. 23: 265.

- Deebel, N.A., et al. Age-related presence of spermatogonia in patients with Klinefelter syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update, 2020. 26: 58.

- Okada, H., et al. Age as a limiting factor for successful sperm retrieval in patients with nonmosaic Klinefelter’s syndrome. Fertil Steril, 2005. 84: 1662.

- Pizzocaro, A., et al. Testosterone treatment in male patients with Klinefelter syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Endocrinol Invest, 2020. 43: 1675.

- Kanakis, G.A., et al. Klinefelter syndrome: more than hypogonadism. Metabolism, 2018. 86: 135.

- Groth, K.A., et al. Clinical review: Klinefelter syndrome–a clinical update. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2013. 98: 20.

- Gravholt, C.H., et al. Klinefelter Syndrome: Integrating Genetics, Neuropsychology, and Endocrinology. Endocr Rev, 2018. 39: 389.

- Glueck, C.J., et al. Thrombophilia in Klinefelter Syndrome With Deep Venous Thrombosis, Pulmonary Embolism, and Mesenteric Artery Thrombosis on Testosterone Therapy: A Pilot Study. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost, 2017. 23: 973.

- Gies, I., et al. Spermatogonial stem cell preservation in boys with Klinefelter syndrome: to bank or not to bank, that’s the question. Fertil Steril, 2012. 98: 284.

- Franik, S., et al. Klinefelter syndrome and fertility: sperm preservation should not be offered to children with Klinefelter syndrome. Hum Reprod, 2016. 31: 1952.

- Ferlin, A., et al. Contemporary genetics-based diagnostics of male infertility. Expert Rev Mol Diagn, 2019. 19: 623.

- Nguyen, M.H., et al. Balanced complex chromosome rearrangement in male infertility: case report and literature review. Andrologia, 2015. 47: 178.

- Siffroi, J.P., et al. Assisted reproductive technology and complex chromosomal rearrangements: the limits of ICSI. Mol Hum Reprod, 1997. 3: 847.

- De Boeck, K. Cystic fibrosis in the year 2020: a disease with a new face. Acta Paediatr, 2020.

- Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive, M. Diagnostic evaluation of the infertile male: a committee opinion. Feril Steril, 2015. 103: e18.

- Oates, R. Evaluation of the azoospermic male. Asian J Androl, 2012. 14: 82.

- Daudin, M., et al. Congenital bilateral absence of the vas deferens: clinical characteristics, biological parameters, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene mutations, and implications for genetic counseling. Feril Steril, 2000. 74: 1164.

- McBride, J.A., et al. Sperm retrieval and intracytoplasmic sperm injection outcomes in men with cystic fibrosis disease versus congenital bilateral absence of the vas deferens. Asian J Androl, 2020.

- Vogt, P.H., et al. Human Y chromosome azoospermia factors (AZF) mapped to different subregions in Yq11. Hum Mol Genet, 1996. 5: 933.

- Krausz, C., et al. Spermatogenic failure and the Y chromosome. Hum Genet, 2017. 136: 637.

- Skaletsky, H., et al. The male-specific region of the human Y chromosome is a mosaic of discrete sequence classes. Nature, 2003. 423: 825.

- Krausz, C., et al. The Y chromosome and male fertility and infertility. Int J Androl, 2003. 26: 70.

- Hinch, A.G., et al. Recombination in the human Pseudoautosomal region PAR1. PLoS Genet, 2014. 10: e1004503.

- Colaco, S., et al. Genetics of the human Y chromosome and its association with male infertility. Reprod Biol Endocrinol, 2018. 16: 14.

- Kohn, T.P., et al. The Prevalence of Y-chromosome Microdeletions in Oligozoospermic Men: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of European and North American Studies. Eur Urol, 2019. 76: 626.

- Ferlin, A., et al. Molecular and clinical characterization of Y chromosome microdeletions in infertile men: a 10-year experience in Italy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2007. 92: 762.

- Hopps, C.V., et al. Detection of sperm in men with Y chromosome microdeletions of the AZFa, AZFb and AZFc regions. Hum Reprod, 2003. 18: 1660.

- Park, S.H., et al. Success rate of microsurgical multiple testicular sperm extraction and sperm presence in the ejaculate in korean men with y chromosome microdeletions. Korean J Urol, 2013. 54: 536.

- Abur, U., et al. Chromosomal and Y-chromosome microdeletion analysis in 1,300 infertile males and the fertility outcome of patients with AZFc microdeletions. Andrologia, 2019. 51: e13402.

- Krausz, C., et al. Y chromosome and male infertility: update, 2006. Front Biosci, 2006. 11: 3049.

- Krausz, C., et al. EAA/EMQN best practice guidelines for molecular diagnosis of Y-chromosomal microdeletions: state-of-the-art 2013. Andrology, 2014. 2: 5.

- Stuppia, L., et al. A quarter of men with idiopathic oligo-azoospermia display chromosomal abnormalities and microdeletions of different types in interval 6 of Yq11. Hum Genet, 1998. 102: 566.

- Le Bourhis, C., et al. Y chromosome microdeletions and germinal mosaicism in infertile males. Mol Hum Reprod, 2000. 6: 688.

- Siffroi, J.P., et al. Sex chromosome mosaicism in males carrying Y chromosome long arm deletions. Hum Reprod, 2000. 15: 2559.

- Patsalis, P.C., et al. Effects of transmission of Y chromosome AZFc deletions. Lancet, 2002. 360: 1222.

- Haltrich, I. Chromosomal Aberrations with Endocrine Relevance (Turner Syndrome, Klinefelter Syndrome, PraderWilli Syndrome). Exp Suppl, 2019. 111: 443.

- Tsang, S.H., et al. Ciliopathy: Bardet-Biedl Syndrome. Adv Exp Med Biol, 2018. 1085: 171.

- Mieusset, R., et al. The spectrum of renal involvement in male patients with infertility related to excretory-system abnormalities: phenotypes, genotypes, and genetic counseling. J Nephrol, 2017. 30: 211.

- Luciano, R.L., et al. Extra-renal manifestations of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD): considerations for routine screening and management. Nephrol Dial Transplant, 2014. 29: 247.

- Van Batavia, J.P., et al. Fertility in disorders of sex development: A review. J Pediatr Urol, 2016. 12: 418.

- Kosti, K., et al. Long-term consequences of androgen insensitivity syndrome. Maturitas, 2019. 127: 51.

- Hsieh, M.H., et al. The genetic and phenotypic basis of infertility in men with pediatric urologic disorders. Urology, 2010. 76: 25.

- Okutman, O., et al. Genetic evaluation of patients with non-syndromic male infertility. J Assist Reprod Genet, 2018. 35: 1939.

- Luo, K., et al. Next-generation sequencing analysis of embryos from mosaic patients undergoing in vitro fertilization and preimplantation genetic testing. Feril Steril, 2019. 112: 291.

- Kohn, T.P., et al. Reproductive outcomes in men with karyotype abnormalities: Case report and review of the literature. Can Urol Assoc, 2015. 9: E667.

- Gianaroli, L., et al. Frequency of aneuploidy in sperm from patients with extremely severe male factor infertility. Hum Reprod, 2005. 20: 2140.

- Pang, M.G., et al. The high incidence of meiotic errors increases with decreased sperm count in severe male factor infertilities. Hum Reprod, 2005. 20: 1688.

- Tempest, H.G., et al. Cytogenetic risks in chromosomally normal infertile men. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol, 2009. 21: 223.

- Baccetti, B., et al. Ultrastructural studies of spermatozoa from infertile males with Robertsonian translocations and 18, X, Y aneuploidies. Hum Reprod, 2005. 20: 2295.

- Rodrigo, L., et al. Sperm chromosomal abnormalities and their contribution to human embryo aneuploidy. Biol Reprod, 2019. 101: 1091.

- Agarwal, A., et al. Sperm DNA damage assessment: a test whose time has come. Fertil Steril, 2005. 84: 850.

- Zini, A., et al. Correlations between two markers of sperm DNA integrity, DNA denaturation and DNA fragmentation, in fertile and infertile men. Fertil Steril, 2001. 75: 674.

- Iommiello, V.M., et al. Ejaculate oxidative stress is related with sperm DNA fragmentation and round cells. Int J Endocrinol, 2015. 2015: 321901.

- Bisht, S., et al. Oxidative stress and male infertility. Nat Rev Urol, 2017. 14: 470.

- Agarwal, A., et al. Oxidation-reduction potential as a new marker for oxidative stress: Correlation to male infertility. Investig Clin Urol, 2017. 58: 385.

- Lu, Y., et al. Long-term follow-up of children conceived through assisted reproductive technology*. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B, 2013. 14: 359.

- Kushnir, V.A., et al. Systematic review of worldwide trends in assisted reproductive technology 2004-2013. Reprod Biol Endocrinol, 2017. 15: 6.

- Rinaudo, P., et al. Transitioning from Infertility-Based (ART 1.0) to Elective (ART 2.0) Use of Assisted Reproductive Technologies and the DOHaD Hypothesis: Do We Need to Change Consenting? Semin Reprod Med, 2018. 36: 204.

- Kallen, B., et al. In vitro fertilization in Sweden: child morbidity including cancer risk. Fertil Steril, 2005. 84: 605.

- Schieve, L.A., et al. Low and very low birth weight in infants conceived with use of assisted reproductive technology. N Engl J Med, 2002. 346: 731.

- Bonduelle, M., et al. A multi-centre cohort study of the physical health of 5-year-old children conceived after intracytoplasmic sperm injection, in vitro fertilization and natural conception. Hum Reprod, 2005. 20: 413.

- El-Chaar, D., et al. Risk of birth defects increased in pregnancies conceived by assisted Human Reprod. Fertil Steril, 2009. 92: 1557.

- Davies, M.J., et al. Reproductive technologies and the risk of birth defects. N Engl J Med, 2012. 366: 1803.

- Rimm, A.A., et al. A meta-analysis of controlled studies comparing major malformation rates in IVF and ICSI infants with naturally conceived children. J Assist Reprod Genet, 2004. 21: 437.

- Hansen, M., et al. Assisted reproductive technologies and the risk of birth defects–a systematic review. Hum Reprod, 2005. 20: 328.

- Wen, J., et al. Birth defects in children conceived by in vitro fertilization and intracytoplasmic sperm injection: a meta-analysis. Fertil Steril, 2012. 97: 1331.

- Rumbold, A.R., et al. Impact of male factor infertility on offspring health and development. Fertil Steril, 2019. 111: 1047.

- La Rovere, M., et al. Epigenetics and Neurological Disorders in ART. Int J Mol Sci, 2019. 20.

- Bertoncelli Tanaka, M., et al. Paternal age and assisted reproductive technology: problem solver or trouble maker? Panminerva Med, 2019. 61: 138.

- Kissin, D.M., et al. Association of assisted reproductive technology (ART) treatment and parental infertility diagnosis with autism in ART-conceived children. Hum Reprod, 2015. 30: 454.

- Pinborg, A., et al. Epigenetics and assisted reproductive technologies. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand, 2016. 95: 10.

- Jiang, Z., et al. Genetic and epigenetic risks of assisted reproduction. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol, 2017. 44: 90.

- Bieniek, J.M., et al. Prevalence and Management of Incidental Small Testicular Masses Discovered on Ultrasonographic Evaluation of Male Infertility. J Urol, 2018. 199: 481.

- Tournaye, H., et al. Novel concepts in the aetiology of male reproductive impairment. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol, 2017. 5: 544.

- Hanson, H.A., et al. Subfertility increases risk of testicular cancer: evidence from population-based semen samples. Fertil Steril, 2016. 105: 322.

- Barbonetti, A., et al. Testicular Cancer in Infertile Men With and Without Testicular Microlithiasis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Case-Control Studies. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 2019. 10: 164.

Author Correspondence:

Prof. Dr. Semir A. Salim. Al Samarrai

Medical Director of Professor Al Samarrai Medical Center.

Dubai Healthcare City, Al-Razi Building 64, Block D, 2nd Floor, Suite 2018

E-mail: semiralsamarrai@hotmail.com

Tel: +97144233669