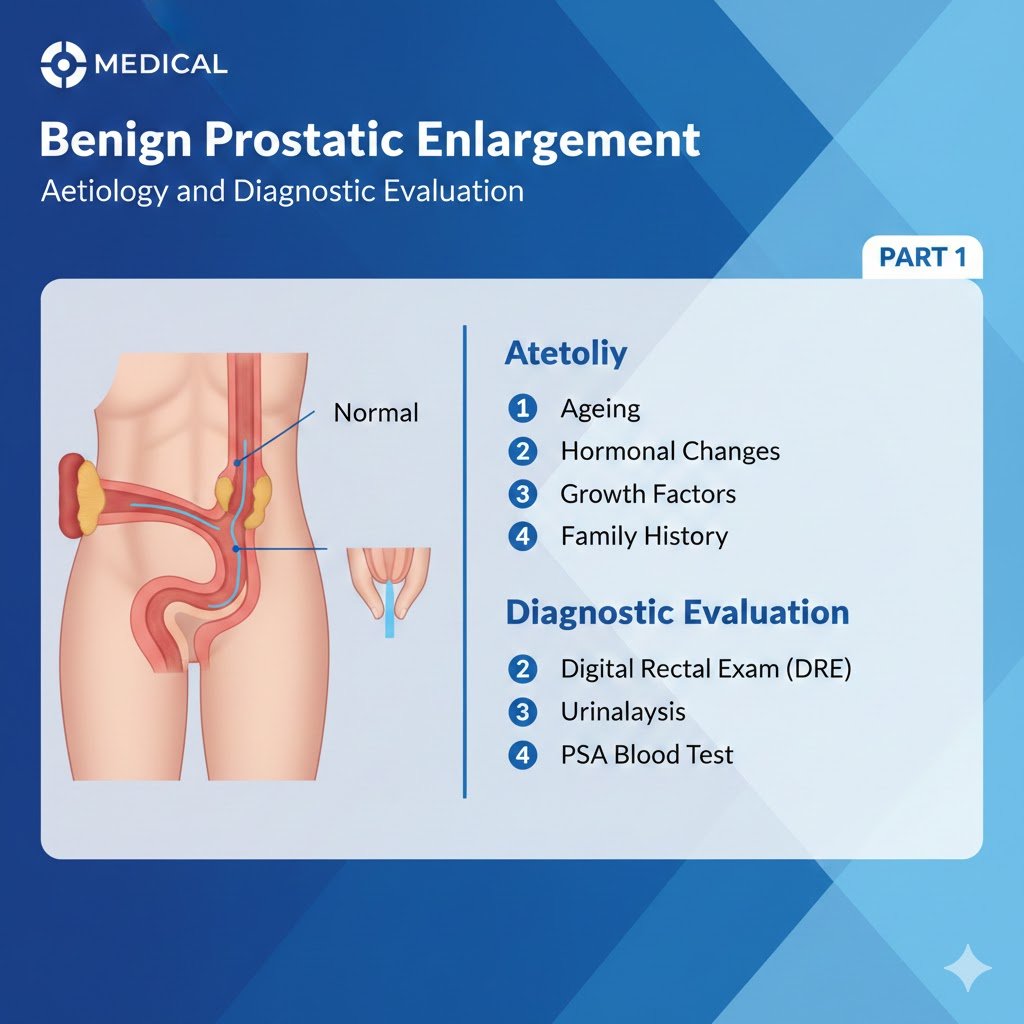

Benign Prostatic Enlargement

Aetiology and Diagnostic Evaluation

PART 1

Comprehensive Review Article

Prof. Dr. Semir. A. Salim. Al Samarrai

Lower urinary tract symptoms can be divided into storage, voiding and post-micturition symptoms [1], they are prevalent, cause bother and impair QoL [2-5]. An increasing awareness of LUTS and storage symptoms in particular, is warranted to discuss management options that could increase QoL [6]. Lower urinary tract symptoms are strongly associated with ageing [2,3], associated costs and burden are therefore likely to increase with future demographic changes [3,7]. Lower urinary tract symptoms are also associated with a number of modifiable risk factors, suggesting potential targets for prevention (e.g. metabolic syndrome) [8]. In addition, men with moderate-to-severe LUTS may have an increased risk of major adverse cardiac events [9]. Most elderly men have at least one LUTS [3]; however, symptoms are often mild or not very bothersome [5, 6, 10]. Lower urinary tract symptoms can progress dynamically: for some individuals LUTS persist and progress over long time periods, and for others they remit [3]. Lower urinary tract symptoms have traditionally been related to bladder outlet obstruction (BOO), most frequently when histological BPH progresses through benign prostatic enlargement (BPE) to BPO [1,4]. However, increasing numbers of studies have shown that LUTS are often unrelated to the prostate [3, 11]. Bladder dysfunction may also cause LUTS, including detrusor overactivity/OAB, detrusor underactivity (DU)/underactive bladder (UAB), as well as other structural or functional abnormalities of the urinary tract and its surrounding tissues [11]. Prostatic inflammation also appears to play a role in BPH pathogenesis and progression [12, 13]. In addition, many non-urological conditions also contribute to urinary symptoms, especially nocturia [3].

The definitions of the most common conditions related to male LUTS are:

• Acute retention of urine is defined as a painful, palpable or percussible bladder, when the patient is unable to pass any urine [1].

• Chronic retention of urine is defined as a non-painful bladder, which remains palpable or percussible after the patient has passed urine. Such patients may be incontinent [1].

• Bladder outlet obstruction is the generic term for obstruction during voiding and is characterised by increasing detrusor pressure and reduced urine flow rate. It is usually diagnosed by studying the synchronous values of flow-rate and detrusor pressure [1].

• Benign prostatic obstruction is a form of BOO and may be diagnosed when the cause of outlet obstruction is known to be BPE [1]. In the Guidelines the term BPO or BOO is used as reported by the original studies.

• Benign prostatic hyperplasia is a term used (and reserved) for the typical histological pattern, which defines the disease.

• Detrusor overactivity is a urodynamic observation characterised by involuntary detrusor contractions during the filling phase which may be spontaneous or provoked [1]. Detrusor overactivity is usually associated with OAB syndrome characterised by urinary urgency, with or without urgency urinary incontinence (UUI), usually with increased daytime frequency and nocturia, if there is no proven infection or other obvious pathology [14].

• Detrusor underactivity during voiding is characterised by decreased detrusor voiding pressure leading to a reduced urine flow rate. Detrusor underactivity causes OAB syndrome which is characterised by voiding symptoms similar to those caused by BPO [15].

The importance of assessing the patient’s history is well recognised [16–18]. A medical history aims to identify the potential causes and relevant comorbidities, including medical and neurological diseases. In addition, current medication, lifestyle habits, emotional and psychological factors must be reviewed. The Panel recognises the need to discuss LUTS and the therapeutic pathway from the patient’s perspective. This includes reassuring the patient that there is no definite link between LUTS and prostate cancer (PCa) [19,20 ]. As part of the urological/surgical history, a self-completed validated symptom questionnaire should be obtained to objectify and quantify LUTS. Bladder diaries or frequency volume charts (FVC) are particularly beneficial when assessing patients with nocturia and/or storage symptoms. Sexual function should also be assessed, preferably with validated symptom questionnaires such as the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) [21].

The IPSS is an eight-item questionnaire, consisting of seven symptom questions and one QoL question [22]. The IPSS score is categorised as ‘asymptomatic’ (0 points), ‘mildly symptomatic’ (1-7 points), ‘moderately symptomatic’ (8-19 points), and ‘severely symptomatic’ (20-35 points). Limitations include lack of assessment of incontinence, post-micturition symptoms, and bother caused by each separate symptom.

The ICIQ-MLUTS was created from the International Continence Society (ICS) male questionnaire. It is a widely used and validated patient completed questionnaire including incontinence questions and bother for each symptom [23]. It contains thirteen items, with subscales for nocturia and OAB, and is available in seventeen languages.

Physical examination particularly focusing on the suprapubic area, the external genitalia, the perineum, and lower limbs should be performed. Urethral discharge, meatal stenosis, phimosis, and penile cancer must be excluded.

Digital-rectal examination (DRE) is the simplest way to assess prostate volume, but the correlation to prostate volume is poor. Quality-control procedures for DRE have been described [24]. Transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) is more accurate in determining prostate volume than DRE. Underestimation of prostate volume by DRE increases with increasing TRUS volume, particularly where the volume is > 30 mL [25]. A model of visual aids has been developed to help urologists estimate prostate volume more accurately [26]. One study concluded that DRE was sufficient to discriminate between prostate volumes > or < 50 mL [27].

Urinalysis (dipstick or sediment) must be included in the primary evaluation of any patient presenting with LUTS to identify conditions, such as urinary tract infections (UTI), microhaematuria and diabetes mellitus. If abnormal findings are detected further tests are recommended according to other EAU Guidelines, e.g., Guidelines on urinary tract cancers and urological infections [28-31]. Urinalysis is recommended in most Guidelines in the primary management of patients with LUTS [32, 33]. There is limited evidence, but general expert consensus suggests that the benefits outweigh the costs [34]. The value of urinary dipstick/microscopy for diagnosing UTI in men with LUTS without acute frequency and dysuria has been questioned [35].

Pooled analysis of placebo-controlled trials of men with LUTS and presumed BPO showed that prostate specific antigen (PSA) has a good predictive value for assessing prostate volume, with areas under the curve (AUC) of 0.76-0.78 for various prostate volume thresholds (30 mL, 40 mL, and 50 mL). To achieve a specificity of 70%, whilst maintaining a sensitivity between 65-70%, approximate age-specific criteria for detecting men with prostate glands exceeding 40 mL are PSA > 1.6 ng/mL, > 2.0 ng/mL, and > 2.3 ng/mL, for men with BPH in their 50s, 60s, and 70s, respectively [36]. A strong association between PSA and prostate volume was found in a large community-based study in the Netherlands [37]. A PSA threshold value of 1.5 ng/mL could best predict a prostate volume of > 30 mL, with a positive predictive value (PPV) of 78%. The prediction of prostate volume can also be based on total and free PSA. Both PSA forms predict the TRUS prostate volume (± 20%) in > 90% of the cases [38, 39].

The role of PSA in the diagnosis of PCa is presented by the EAU Guidelines on Prostate Cancer [40]. The potential benefits and harms of using serum PSA testing to diagnose PCa in men with LUTS should be discussed with the patient.

Serum PSA is a stronger predictor of prostate growth than prostate volume [41]. In addition, the PLESS study showed that PSA also predicted the changes in symptoms, QoL/bother, and maximum flow-rate (Qmax) [42]. In a longitudinal study of men managed conservatively, PSA was a highly significant predictor of clinical progression [43, 44]. In the placebo arms of large double-blind studies, baseline serum PSA predicted the risk of acute urinary retention (AUR) and BPO-related surgery [45, 46]. An equivalent link was also confirmed by the Olmsted County Study. The risk for treatment was higher in men with a baseline PSA of > 1.4 ng/mL [47]. Patients with BPO seem to have a higher PSA level and larger prostate volumes. The Positive Predictive Value (PPV) of PSA for the detection of BPO was recently shown to be 68% [48]. Furthermore, in an epidemiological study, elevated free PSA levels could predict clinical BPH, independent of total PSA levels [49].

Renal function may be assessed by serum creatinine or estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). Hydronephrosis, renal insufficiency or urinary retention are more prevalent in patients with signs or symptoms of BPO [50]. Even though BPO may be responsible for these complications, there is no conclusive evidence on the mechanism [51]. One study reported that 11% of men with LUTS had renal insufficiency [50]. Neither symptom score nor QoL was associated with the serum creatinine level. Diabetes mellitus or hypertension were the most likely causes of the elevated creatinine concentration. Comiter et al., [52] reported that non-neurogenic voiding dysfunction is not a risk factor for elevated creatinine levels. Koch et al., [53] concluded that only those with an elevated creatinine level require investigational ultrasound (US) of the kidney. In the Olmsted County Study community-dwelling men there was a cross-sectional association between signs and symptoms of BPO (though not prostate volume) and chronic kidney disease (CKD) [54]. In 2,741 consecutive patients who presented with LUTS, decreased Qmax, a history of hypertension and/or diabetes were associated with CKD [55]. Another study demonstrated a correlation between Qmax and eGFR in middle-aged men with moderate-to-severe LUTS [56]. Patients with renal insufficiency are at an increased risk of developing post-operative complications [57].

Post-void residual (PVR) urine can be assessed by transabdominal US, bladder scan or catheterisation. Post-void residual is not necessarily associated with BOO, since high PVR volumes can be a consequence of obstruction and/or poor detrusor function/DU [58, 59]. Using a PVR threshold of 50 mL, the diagnostic accuracy of PVR measurement has a PPV of 63% and a negative predictive value (NPV) of 52% for the prediction of BOO [60]. A large PVR is not a contraindication to watchful waiting (WW) or medical therapy, although it may indicate a poor response to treatment and especially to WW. In both the MTOPS and ALTESS studies, a high baseline PVR was associated with an increased risk of symptom progression [45, 46]. Monitoring of changes in PVR over time may allow for identification of patients at risk of AUR [61]. This is of particular importance for the treatment of patients using antimuscarinic medication. In contrast, baseline PVR has little prognostic value for the risk of BPO-related invasive therapy in patients on α1-blockers or WW [62]. However, due to large test-retest variability and lack of outcome studies, no PVR threshold for treatment decision has yet been established; this is a research priority.

Urinary flow rate assessment is a widely used non-invasive urodynamic test. Key parameters are Qmax and flow pattern. Uroflowmetry parameters should preferably be evaluated with voided volume > 150 mL. As Qmax is prone to within-subject variation [63, 64], it is useful to repeat uroflowmetry measurements, especially if the voided volume is < 150 mL, or Qmax or flow pattern is abnormal. The diagnostic accuracy of uroflowmetry for detecting BOO varies considerably and is substantially influenced by threshold values. A threshold Qmax of 10 mL/s has a specificity of 70%, a PPV of 70% and a sensitivity of 47% for BOO. The specificity using a threshold Qmax of 15 mL/s was 38%, the PPV 67% and the sensitivity 82% [65]. If Qmax is > 15 mL/s, physiological compensatory processes mean that BOO cannot be excluded. Low Qmax can arise as a consequence of BOO [66], DU or an under-filled bladder [67]. Therefore, it is limited as a diagnostic test as it is unable to discriminate between the underlying mechanisms. Specificity can be improved by repeated flow rate testing. Uroflowmetry can be used for monitoring treatment outcomes [68] and correlating symptoms with objective findings.

Men with LUTS are not at increased risk for upper tract malignancy or other abnormalities when compared to the overall population [53, 69-71]. Several arguments support the use of renal ultrasound (US) in preference to intravenous urography. Ultrasound allows for better characterisation of renal masses, the possibility of investigating the liver and retroperitoneum, and simultaneous evaluation of the bladder, PVR and prostate, together with a lower cost, no radiation dose and less side effects [69]. Ultrasound can be used for the evaluation of men with large PVR, haematuria, or a history of urolithiasis.

Imaging of the prostate can be performed by transabdominal US, TRUS, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). However, in daily practice, prostate imaging is performed by transabdominal (suprapubic) US or TRUS [69].

Assessment of prostate size is important for the selection of interventional treatment, i.e., open prostatectomy (OP), enucleation techniques, transurethral resection, transurethral incision of the prostate (TUIP), or minimally invasive therapies. It is also important prior to treatment with 5α-reductase inhibitors (5-ARIs). Prostate volume predicts symptom progression and the risk of complications [71]. Transrectal US is superior to transabdominal volume measurement [72, 73]. The presence of a median lobe may guide treatment choice in patients scheduled for a minimally invasive approach since medial lobe presence can be a contraindication for some minimally invasive treatments.

Voiding cysto-urethrogram (VCUG) is not recommended in the routine diagnostic work-up of men with LUTS, but it may be useful for the detection of vesico-ureteral reflux, bladder diverticula, or urethral pathologies. Retrograde urethrography may additionally be useful for the evaluation of suspected urethral strictures.

Patients with a history of microscopic or gross haematuria, urethral stricture, or bladder cancer, who present with LUTS, should undergo urethrocystoscopy during diagnostic evaluation. The evaluation of a prostatic middle lobe with urethrocystoscopy should be performed when considering interventional treatments for which the presence of middle lobe is a contraindication. A prospective study evaluated 122 patients with LUTS using uroflowmetry and urethrocystoscopy [74]. The pre-operative Qmax was normal in 25% of 60 patients who had no bladder trabeculation, 21% of 73 patients with mild trabeculation and 12% of 40 patients with marked trabeculation on cystoscopy. All 21 patients who presented with diverticula had a reduced Qmax.

Another study showed that there was no significant correlation between the degree of bladder trabeculation (graded from I to IV), and the pre-operative Qmax value in 39 symptomatic men aged 53-83 years [75]. The largest study published on this issue examined the relation of urethroscopic findings to urodynamic studies in 492 elderly men with LUTS [76]. The authors noted a correlation between cystoscopic appearance (grade of bladder trabeculation and urethral occlusion) and urodynamic indices, Detrusor Overactivity (DO) and low compliance. It should be noted, however, that BOO was present in 15% of patients with normal cystoscopic findings, while 8% of patients had no obstruction, even in the presence of severe trabeculation [76].

In male LUTS, the most widespread invasive urodynamic techniques employed are filling cystometry and pressure flow studies (PFS). The major goal of urodynamics (UDS) is to explore the functional mechanisms of LUTS, to identify risk factors for adverse outcomes and to provide information for shared decision-making. Most terms and conditions (e.g. DO, low compliance, BOO/BPO, DU) are defined by urodynamic investigation.

Pressure flow studies are used to diagnose and define the severity of BOO, which is characterised by increased detrusor pressure and decreased urinary flow rate during voiding. Bladder outlet obstruction/BPO has to be differentiated from Detrusor Underactivity (DU), which exhibits decreased detrusor pressure during voiding in combination with decreased urinary flow rate [1]. Urodynamic testing may also identify DO. Studies have described an association between BOO and DO [77,78]. In men with LUTS attributed to BPO, DO was present in 61% and independently associated with BOO grade and ageing [77]. The prevalence of DU in men with LUTS is 11-40% [79,80]. Detrusor contractility does not appear to decline in long-term BOO and surgical relief of BOO does not improve contractility [81,82]. An RCT investigated whether urodynamics would reduce surgery without increasing urinary symptoms. The UPSTREAM study was a non-inferiority, RCT in men with bothersome LUTS, in whom surgery was an option, in 26 hospitals in England. From the 820 men, 153/408 (38%) were in the UDS arm and received surgery compared with 138/384 (36%) in the routine care (RC) arm. A total of 428 adverse events were recorded, with related events similar in both arms and eleven unrelated deaths. The UDS group was non-inferior to the RC group for IPSS, but UDS did not reduce surgical rates. The authors concluded that routine use of UDS in the evaluation of uncomplicated LUTS has a limited role and should be used selectively [83]. If urodynamic investigation is performed, a rigorous quality control is mandatory [84]. Due to the invasive nature of the test, a urodynamic investigation is generally only offered if conservative treatment has failed.

Prostatic configuration can be evaluated with TRUS, using the concept of the presumed circle area ratio (PCAR) [85]. The PCAR evaluates how closely the transverse US image of the prostate approaches a circular shape. The ratio tends toward one as the prostate becomes more circular. The sensitivity of PCAR was 77% for diagnosing BPO when PCAR was > 0.8, with 75% specificity [85]. Ultrasound measurement of intravesical prostatic protrusion (IPP) assesses the distance between the tip of the prostate median lobe and bladder neck in the midsagittal plane, using a suprapubically positioned US scanner, with a bladder volume of 150-250 mL; grade I protrusion is 0-4.9 mm, grade II is 5-10 mm and grade III is > 10 mm. Intravesical prostatic protrusion correlates well with BPO (presence and severity) on urodynamic testing, with a PPV of 94% and a NPV of 79% [86]. Intravesical prostatic protrusion may also correlate with prostate volume, DO, bladder compliance, detrusor pressure at maximum urinary flow, BOO index and PVR, and negatively correlates with Qmax [87]. Furthermore, IPP also appears to successfully predict the outcome of a trial without catheter after AUR [88,89]. However, no information with regards to intra- or inter-observer variability and learning curve is yet available. Therefore, whilst IPP may be a feasible option to infer BPO in men with LUTS, the role of IPP as a non-invasive alternative to PFS in the assessment of male LUTS remains under evaluation.

For bladder wall thickness (BWT) assessment, the distance between the mucosa and the adventitia is measured. For detrusor wall thickness (DWT) assessment, the only measurement needed is the detrusor sandwiched between the mucosa and adventitia [90]. A correlation between BWT and PFS parameters has been reported. A threshold value of 5 mm at the anterior bladder wall with a bladder filling of 150 mL was best at differentiating between patients with or without BOO [91]. Detrusor wall thickness at the anterior bladder wall with a bladder filling > 250 mL (threshold value for BOO > 2 mm) has a PPV of 94% and a specificity of 95%, achieving 89% agreement with pressure-flow studies PFS [53]. Threshold values of 2.0, 2.5, or 2.9 mm for DWT in patients with LUTS are able to identify 81%, 89%, and 100% of patients with BOO, respectively [92]. All studies found that BWT or DWT measurements have a higher diagnostic accuracy for detecting BOO than Qmax or Qave of free uroflowmetry, measurements of PVR, prostate volume, or symptom severity. One study could not demonstrate any difference in BWT between patients with normal UDS, BOO or DO. However, the study did not use a specific bladder filling volume for measuring BWT [93]. Disadvantages of the method include the lack of standardisation, and lack of evidence to indicate which measurement (BWT/DWT) is preferable [94]. Measurement of BWT/DWT is therefore not recommended for the diagnostic work-up of men with LUTS. Ultrasound-estimated bladder weight (UEBW) may identify BOO with a diagnostic accuracy of 86% at a cut-off value of 35 g [95,96]. Severe LUTS and a high UEBW (> 35 g) are risk factors for prostate/BPH surgery in men on α-blockers [97].

The penile cuff method, in which flow is interrupted to estimate isovolumetric bladder pressure, shows promising data, with good test repeatability [98] and interobserver agreement [99]. A nomogram has also been derived [100] whilst a method in which flow is not interrupted is also under investigation [101].

The data generated with the external condom method [102] correlates with invasive PFS in a high proportion of patients [103]. Resistive index [104] and prostatic urethral angle [105] have also been proposed, but are still experimental.

The diagnostic performance of non-invasive tests in diagnosing BOO in men with LUTS compared with PFS has been investigated in a SR [106]. A total of 42 studies were included is this review. The majority were prospective cohort studies, and the diagnostic accuracy of the following non-invasive tests were assessed: penile cuff test; uroflowmetry; DWT/BWT; bladder weight; external condom catheter method; IPP; Doppler US; prostate volume/height; and near-infrared spectroscopy. Overall, although the majority of studies have a low risk of bias, data regarding the diagnostic accuracy of these non-invasive tests is limited by the heterogeneity of the studies in terms of the threshold values used to define BOO, the different urodynamic definitions of BOO used across different studies and the small number of studies for each test. It was found that specificity, sensitivity, PPV and NPV of the non-invasive tests were highly variable. Therefore, even though several tests have shown promising results regarding non-invasive diagnosis of BOO, invasive urodynamics remains the modality of choice.

A novel visual prostate symptom score (VPSS) has been prospectively tested vs. the IPSS and correlated positively with the IPSS score [107, 108]. This visual score can be used as an option in men with limited literacy.

The use of Micro RNA has been shown to have the potential to be used as a biomarker and novel target in the early diagnosis and therapy of BPH [109].

REFERENCES:

1. Abrams, P., et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn, 2002. 21: 167. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11857671/

2. Martin, S.A., et al. Prevalence and factors associated with uncomplicated storage and voiding lower urinary tract symptoms in community-dwelling Australian men. World J Urol, 2011. 29: 179. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20963421/

3. Société Internationale d’Urologie (SIU), Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (LUTS): An International Consultation on Male LUTS. C. Chapple & P. Abrams, Editors. 2013. https://www.siu-urology.org/themes/web/assets/files/ICUD/pdf/Male%20Lower%20Urinary%20 Tract%20Symptoms%20(LUTS).

6. Kupelian, V., et al. Prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms and effect on quality of life in a racially and ethnically diverse random sample: the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey. Arch Intern Med, 2006. 166: 2381. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17130393/

5. Agarwal, A., et al. What is the most bothersome lower urinary tract symptom? Individual- and population-level perspectives for both men and women. Eur Urol, 2014. 65: 1211. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24486308/

6. De Ridder, D., et al. Urgency and other lower urinary tract symptoms in men aged ≥ 40 years: a Belgian epidemiological survey using the ICIQ-MLUTS questionnaire. Int J Clin Pract, 2015. 69: 358. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25648652/

7. Taub, D.A., et al. The economics of benign prostatic hyperplasia and lower urinary tract symptoms in the United States. Curr Urol Rep, 2006. 7: 272. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16930498/

8. Gacci, M., et al. Metabolic syndrome and benign prostatic enlargement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJU Int, 2015. 115: 24. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24602293/

9. Gacci, M., et al. Male Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms and Cardiovascular Events: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Eur Urol, 2016. 70: 788. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27451136/

10. Kogan, M.I., et al. Epidemiology and impact of urinary incontinence, overactive bladder, and other lower urinary tract symptoms: results of the EPIC survey in Russia, Czech Republic, and Turkey. Curr Med Res Opin, 2014. 30: 2119. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24932562/

11. Chapple, C.R., et al. Lower urinary tract symptoms revisited: a broader clinical perspective. Eur Urol, 2008. 54: 563. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18423969/

12. Ficarra, V., et al. The role of inflammation in lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) due to benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and its potential impact on medical therapy. Curr Urol Rep, 2014. 15: 463. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25312251/

13. He, Q., et al. Metabolic syndrome, inflammation and lower urinary tract symptoms: possible translational links. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis, 2016.

14. 7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26391088/ 19. Drake, M.J. Do we need a new definition of the overactive bladder syndrome? ICI-RS 2013. Neurourol Urodyn, 2014. 33: 622. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24838519/

15. Chapple, C.R., et al. Terminology report from the International Continence Society (ICS) Working Group on Underactive Bladder (UAB). Neurourol Urodyn, 2018. 37: 2928. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30203560/

16. Novara, G., et al. Critical Review of Guidelines for BPH Diagnosis and Treatment Strategy. Eur Urol Suppl 2006. 4: 418. https://www.eu-openscience.europeanurology.com/article/S1569-9056(06)00012-1/fulltext

17. McVary, K.T., et al. Update on AUA guideline on the management of benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol, 2011. 185: 1793. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21420124/

18. Bosch, J., et al. Etiology, Patient Assessment and Predicting Outcome from Therapy. International Consultation on Urological Diseases Male LUTS Guideline 2013. https://snucm.elsevierpure.com/en/publications/lower-urinary-tract-symptoms-in-men-male-lutsetiology-patient-as

19. Martin, R.M., et al. Lower urinary tract symptoms and risk of prostate cancer: the HUNT 2 Cohort, Norway. Int J Cancer, 2008. 123: 1924. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18661522/

20. Young, J.M., et al. Are men with lower urinary tract symptoms at increased risk of prostate cancer? A systematic review and critique of the available evidence. BJU Int, 2000. 85: 1037. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10848691/

21. De Nunzio, C., et al. Erectile Dysfunction and Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms. Eur Urol Focus, 2017. 3: 352. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29191671/

22. Barry, M.J., et al. The American Urological Association symptom index for benign prostatic hyperplasia. The Measurement Committee of the American Urological Association. J Urol, 1992. 148: 1549. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1279218/

23. Donovan, J.L., et al. Scoring the short form ICSmaleSF questionnaire. International Continence Society. J Urol, 2000. 164: 1948. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11061889/

24. Weissfeld, J.L., et al. Quality control of cancer screening examination procedures in the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial. Control Clin Trials, 2000. 21: 390s. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11189690/

25. Roehrborn, C.G. Accurate determination of prostate size via digital rectal examination and transrectal ultrasound. Urology, 1998. 51: 19. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9586592/

26. Roehrborn, C.G., et al. Interexaminer reliability and validity of a three-dimensional model to assess prostate volume by digital rectal examination. Urology, 2001. 57: 1087. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11377314/

27. Bosch, J.L., et al. Validity of digital rectal examination and serum prostate specific antigen in the estimation of prostate volume in community-based men aged 50 to 78 years: the Krimpen Study. Eur Urol, 2004. 46: 753. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15548443/

28. Babjuk, M., et al. EAU Guidelines on Non-muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer Edn. presented at EAU Annual Congress, Amsterdam 2022. https://uroweb.org/guideline/non-muscle-invasive-bladder-cancer

29. Bonkat, G., et al. EAU Guidelines on Urological Infections Edn. presented at EAU Annual Congress, Amsterdam, 2022. https://uroweb.org/guideline/urological-infections/

30. Palou, J., et al. ICUD-EAU International Consultation on Bladder Cancer 2012: Urothelial carcinoma of the prostate. Eur Urol, 2013. 63: 81. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22938869/

31. Roupret, M., et al. EAU Guidelines on Upper Urinary Tract Urothelial Cell Carcinoma Edn. presented at EAU Annual Congress, Amsterdam, 2022. https://uroweb.org/guideline/upper-urinary-tract-urothelial-cell-carcinoma/

32. Roehrborn, C.G., et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia: a

comparative, international overview. Urology, 2001. 58: 642.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11711329/

33. Abrams, P., et al. Evaluation and treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms in older men. J Urol,

2013. 189: S93.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23234640/

34. Medicine., E.C.o.L. European urinalysis guidelines. Scand J Clin Lab Invest Suppl, 2000. 231: 1.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12647764/

35. Khasriya, R., et al. The inadequacy of urinary dipstick and microscopy as surrogate markers of

urinary tract infection in urological outpatients with lower urinary tract symptoms without acute

frequency and dysuria. J Urol, 2010. 183: 1843.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20303096/

36. Roehrborn, C.G., et al. Serum prostate-specific antigen as a predictor of prostate volume in men

with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology, 1999. 53: 581.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10096388/

37. Bohnen, A.M., et al. Serum prostate-specific antigen as a predictor of prostate volume in the

community: the Krimpen study. Eur Urol, 2007. 51: 1645.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17320271/

38. Kayikci, A., et al. Free prostate-specific antigen is a better tool than total prostate-specific antigen at

predicting prostate volume in patients with lower urinary tract symptoms. Urology, 2012. 80: 1088.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23107399/

39. Morote, J., et al. Prediction of prostate volume based on total and free serum prostate-specific

antigen: is it reliable? Eur Urol, 2000. 38: 91.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10859448/

40. Mottet, N., et al., EAU Guidelines on Prostate Cancer. Edn. presented at the EAU Annual Congress

Amsterdam, 2022.

https://uroweb.org/guideline/prostate-cancer/

41. Roehrborn, C.G., et al. Serum prostate specific antigen is a strong predictor of future prostate

growth in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. PROSCAR long-term efficacy and safety study.

J Urol, 2000. 163: 13.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10604304/

42. Roehrborn, C.G., et al. Serum prostate-specific antigen and prostate volume predict long-term

changes in symptoms and flow rate: results of a four-year, randomized trial comparing finasteride

versus placebo. PLESS Study Group. Urology, 1999. 54: 662.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10510925/

43. Djavan, B., et al. Longitudinal study of men with mild symptoms of bladder outlet obstruction

treated with watchful waiting for four years. Urology, 2004. 64: 1144.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15596187/

44. Patel, D.N., et al. PSA predicts development of incident lower urinary tract symptoms: Results from

the REDUCE study. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis, 2018. 21: 238.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29795141/

45. McConnell, J.D., et al. The long-term effect of doxazosin, finasteride, and combination therapy on

the clinical progression of benign prostatic hyperplasia. N Engl J Med, 2003. 349: 2387.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14681504/

46. Roehrborn, C.G. Alfuzosin 10 mg once daily prevents overall clinical progression of benign prostatic

hyperplasia but not acute urinary retention: results of a 2-year placebo-controlled study. BJU Int,

2006. 97: 734.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16536764/

47. Jacobsen, S.J., et al. Treatment for benign prostatic hyperplasia among community dwelling men:

the Olmsted County study of urinary symptoms and health status. J Urol, 1999. 162: 1301.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10492184/

48. Lim, K.B., et al. Comparison of intravesical prostatic protrusion, prostate volume and serum

prostatic-specific antigen in the evaluation of bladder outlet obstruction. Int J Urol, 2006. 13: 1509.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17118026/

49. Meigs, J.B., et al. Risk factors for clinical benign prostatic hyperplasia in a community-based

population of healthy aging men. J Clin Epidemiol, 2001. 54: 935.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11520654/

50. Gerber, G.S., et al. Serum creatinine measurements in men with lower urinary tract symptoms

secondary to benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology, 1997. 49: 697.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9145973/

51. Oelke, M., et al. Can we identify men who will have complications from benign prostatic obstruction

(BPO)? ICI-RS 2011. Neurourol Urodyn, 2012. 31: 322.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22415947/

52. Comiter, C.V., et al. Urodynamic risk factors for renal dysfunction in men with obstructive and

nonobstructive voiding dysfunction. J Urol, 1997. 158: 181.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9186351/

53. Koch, W.F., et al. The outcome of renal ultrasound in the assessment of 556 consecutive patients

with benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol, 1996. 155: 186.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7490828/

54. Rule, A.D., et al. The association between benign prostatic hyperplasia and chronic kidney disease

in community-dwelling men. Kidney Int, 2005. 67: 2376.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15882282/

55. Hong, S.K., et al. Chronic kidney disease among men with lower urinary tract symptoms due to

benign prostatic hyperplasia. BJU Int, 2010. 105: 1424.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19874305/

56. Lee, J.H., et al. Relationship of estimated glomerular filtration rate with lower urinary tract

symptoms/benign prostatic hyperplasia measures in middle-aged men with moderate to severe

lower urinary tract symptoms. Urology, 2013. 82: 1381.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24063940/

57. Mebust, W.K., et al. Transurethral prostatectomy: immediate and postoperative complications. A

cooperative study of 13 participating institutions evaluating 3,885 patients. J Urol, 1989. 141: 243.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2643719/

58. Rule, A.D., et al. Longitudinal changes in post-void residual and voided volume among community

dwelling men. J Urol, 2005. 174: 1317.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16145411/

59. Sullivan, M.P., et al. Detrusor contractility and compliance characteristics in adult male patients with

obstructive and nonobstructive voiding dysfunction. J Urol, 1996. 155: 1995.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8618307/

60. Oelke, M., et al. Diagnostic accuracy of noninvasive tests to evaluate bladder outlet obstruction in

men: detrusor wall thickness, uroflowmetry, postvoid residual urine, and prostate volume. Eur Urol,

2007. 52: 827.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17207910/

61. Emberton, M. Definition of at-risk patients: dynamic variables. BJU Int, 2006. 97 Suppl 2: 12.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16507047/

62. Mochtar, C.A., et al. Post-void residual urine volume is not a good predictor of the need for invasive

therapy among patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol, 2006. 175: 213.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16406914/

63. Jorgensen, J.B., et al. Age-related variation in urinary flow variables and flow curve patterns in

elderly males. Br J Urol, 1992. 69: 265.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1373664/

64. Kranse, R., et al. Causes for variability in repeated pressure-flow measurements. Urology, 2003.

61: 930.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12736007/

65. Reynard, J.M., et al. The ICS-’BPH’ Study: uroflowmetry, lower urinary tract symptoms and bladder

outlet obstruction. Br J Urol, 1998. 82: 619.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9839573/

66. Idzenga, T., et al. Accuracy of maximum flow rate for diagnosing bladder outlet obstruction can be

estimated from the ICS nomogram. Neurourol Urodyn, 2008. 27: 97.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17600368/

67. Siroky, M.B., et al. The flow rate nomogram: I. Development. J Urol, 1979. 122: 665.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/159366/

68. Siroky, M.B., et al. The flow rate nomogram: II. Clinical correlation. J Urol, 1980. 123: 208.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7354519/

69. Grossfeld, G.D., et al. Benign prostatic hyperplasia: clinical overview and value of diagnostic

imaging. Radiol Clin North Am, 2000. 38: 31.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10664665/

70. Thorpe, A., et al. Benign prostatic hyperplasia. Lancet, 2003. 361: 1359.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12711484/

71. Wilkinson, A.G., et al. Is pre-operative imaging of the urinary tract worthwhile in the assessment of

prostatism? Br J Urol, 1992. 70: 53.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1379105/

72. Loch, A.C., et al. Technical and anatomical essentials for transrectal ultrasound of the prostate.

World J Urol, 2007. 25: 361.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17701043/

73. Stravodimos, K.G., et al. TRUS versus transabdominal ultrasound as a predictor of enucleated

adenoma weight in patients with BPH: a tool for standard preoperative work-up? Int Urol Nephrol,

2009. 41: 767.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19350408/

74. Shoukry, I., et al. Role of uroflowmetry in the assessment of lower urinary tract obstruction in adult

males. Br J Urol, 1975. 47: 559.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1191927/

75. Anikwe, R.M. Correlations between clinical findings and urinary flow rate in benign prostatic

hypertrophy. Int Surg, 1976. 61: 392.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/61184/

76. el Din, K.E., et al. The correlation between bladder outlet obstruction and lower urinary tract

symptoms as measured by the international prostate symptom score. J Urol, 1996. 156: 1020.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8709300/

77. Oelke, M., et al. Age and bladder outlet obstruction are independently associated with detrusor

overactivity in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Eur Urol, 2008. 54: 419.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18325657/

78. Oh, M.M., et al. Is there a correlation between the presence of idiopathic detrusor overactivity and

the degree of bladder outlet obstruction? Urology, 2011. 77: 167.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20934743/

79. Jeong, S.J., et al. Prevalence and Clinical Features of Detrusor Underactivity among Elderly with

Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms: A Comparison between Men and Women. Korean J Urol, 2012.

53: 342.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22670194/

80. Thomas, A.W., et al. The natural history of lower urinary tract dysfunction in men: the influence of

detrusor underactivity on the outcome after transurethral resection of the prostate with a minimum

10-year urodynamic follow-up. BJU Int, 2004. 93: 745.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15049984/

81. Al-Hayek, S., et al. Natural history of detrusor contractility–minimum ten-year urodynamic followup

in men with bladder outlet obstruction and those with detrusor. Scand J Urol Nephrol Suppl,

2004: 101.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15545204/

82. Thomas, A.W., et al. The natural history of lower urinary tract dysfunction in men: minimum 10-year

urodynamic followup of transurethral resection of prostate for bladder outlet obstruction. J Urol,

2005. 174: 1887.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16217330/

83. Drake, M.J., et al. Diagnostic Assessment of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms in Men Considering

Prostate Surgery: A Noninferiority Randomised Controlled Trial of Urodynamics in 26 Hospitals. Eur

J, 2020. 78: 701.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32616406/

84. Aiello, M., et al. Quality control of uroflowmetry and urodynamic data from two large multicenter

studies of male lower urinary tract symptoms. Neurourol Urodyn, 2020. 39: 1170.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32187720/

85. Kojima, M., et al. Correlation of presumed circle area ratio with infravesical obstruction in men with

lower urinary tract symptoms. Urology, 1997. 50: 548.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9338730/

86. Chia, S.J., et al. Correlation of intravesical prostatic protrusion with bladder outlet obstruction. BJU

Int, 2003. 91: 371.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12603417/

87. Keqin, Z., et al. Clinical significance of intravesical prostatic protrusion in patients with benign

prostatic enlargement. Urology, 2007. 70: 1096.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18158025/

88. Mariappan, P., et al. Intravesical prostatic protrusion is better than prostate volume in predicting the

outcome of trial without catheter in white men presenting with acute urinary retention: a prospective

clinical study. J Urol, 2007. 178: 573.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17570437/

89. Tan, Y.H., et al. Intravesical prostatic pr

otrusion predicts the outcome of a trial without catheter

following acute urine retention. J Urol, 2003. 170: 2339.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14634410/

90. Arnolds, M., et al. Positioning invasive versus noninvasive urodynamics in the assessment of

bladder outlet obstruction. Curr Opin Urol, 2009. 19: 55.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19057217/

91. Manieri, C., et al. The diagnosis of bladder outlet obstruction in men by ultrasound measurement of

bladder wall thickness. J Urol, 1998. 159: 761.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9474143/

92. Kessler, T.M., et al. Ultrasound assessment of detrusor thickness in men-can it predict bladder

outlet obstruction and replace pressure flow study? J Urol, 2006. 175: 2170.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16697831/

93. Blatt, A.H., et al. Ultrasound measurement of bladder wall thickness in the assessment of voiding

dysfunction. J Urol, 2008. 179: 2275.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18423703/

94. Oelke, M. International Consultation on Incontinence-Research Society (ICI-RS) report on noninvasive

urodynamics: the need of standardization of ultrasound bladder and detrusor wall thickness

measurements to quantify bladder wall hypertrophy. Neurourol Urodyn, 2010. 29: 634.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20432327/

95. Kojima, M., et al. Ultrasonic estimation of bladder weight as a measure of bladder hypertrophy in

men with infravesical obstruction: a preliminary report. Urology, 1996. 47: 942.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8677600/

96. Kojima, M., et al. Noninvasive quantitative estimation of infravesical obstruction using ultrasonic

measurement of bladder weight. J Urol, 1997. 157: 476.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8996337/

97. Akino, H., et al. Ultrasound-estimated bladder weight predicts risk of surgery for benign prostatic

hyperplasia in men using alpha-adrenoceptor blocker for LUTS. Urology, 2008. 72: 817.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18597835/

98. McIntosh, S.L., et al. Noninvasive assessment of bladder contractility in men. J Urol, 2004. 172: 1394.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15371853/

99. Drinnan, M.J., et al. Inter-observer agreement in the estimation of bladder pressure using a penile

cuff. Neurourol Urodyn, 2003. 22: 296.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12808703/

100. Griffiths, C.J., et al. A nomogram to classify men with lower urinary tract symptoms using urine flow

and noninvasive measurement of bladder pressure. J Urol, 2005. 174: 1323.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16145412/

101. Clarkson, B., et al. Continuous non-invasive measurement of bladder voiding pressure using an

experimental constant low-flow test. Neurourol Urodyn, 2012. 31: 557.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22190105/

102. Van Mastrigt, R., et al. Towards a noninvasive urodynamic diagnosis of infravesical obstruction. BJU

Int, 1999. 84: 195.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10444152/

103. Pel, J.J., et al. Development of a non-invasive strategy to classify bladder outlet obstruction in male

patients with LUTS. Neurourol Urodyn, 2002. 21: 117.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11857664/

104. Shinbo, H., et al. Application of ultrasonography and the resistive index for evaluating bladder outlet

obstruction in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Curr Urol Rep, 2011. 12: 255.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21475953/

105. Ku, J.H., et al. Correlation between prostatic urethral angle and bladder outlet obstruction index in

patients with lower urinary tract symptoms. Urology, 2010. 75: 1467.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19962734/

106. Malde, S., et al. Systematic Review of the Performance of Noninvasive Tests in Diagnosing Bladder

Outlet Obstruction in Men with Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms. Eur Urol, 2016.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27687821/

107. Els, M., et al. Prospective comparison of the novel visual prostate symptom score (VPSS) versus the

international prostate symptom score (IPSS), and assessment of patient pain perception with regard

to transrectal ultrasound guided prostate biopsy. Int Braz J Urol, 2019. 45: 137.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30620160/

108. Sanman, K.N., et al. Can new, improvised Visual Prostate Symptom Score replace the International

Prostate Symptom Score? Indian perspective. Indian J Urol, 2020. 36: 123.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32549664/

109. Grosso, G., et al. The Potential Role of MicroRNAs as Biomarkers in Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: A

Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Eur Urol Focus, 2019. 5: 497.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29398458/

Author Correspondence:

Prof. Dr. Semir A. Salim. Al Samarrai

Medical Director of Professor Al Samarrai Medical Center.

Dubai Healthcare City, Al-Razi Building 64, Block D, 2nd Floor, Suite 2018

E-mail: semiralsamarrai@hotmail.com

Tel: +97144233669