Benign Prostatic Enlargement

Pharmacological treatment, plant Extracts-phytotherapy

PART 2

Comprehensive Review Article

Prof. Dr. Semir. A. Salim. Al Samarrai

As conservative treatment, the watchful waiting strategy (WWS) is a viable option for benign prostatic enlargement disease management.

Many men with LUTS are not troubled enough by their symptoms to need drug treatment or surgical intervention. All men with LUTS should be formally assessed prior to any allocation of treatment in order to establish symptom severity and to differentiate between men with uncomplicated (the majority) and complicated LUTS. Watchful waiting strategy (WWS) is a viable option for many men with non-bothersome LUTS as few will progress to AUR and complications (e.g. renal insufficiency or stones) [1,2], whilst others can remain stable for years [3]. In one study, approximately 85% of men with mild LUTS were stable on Watchful waiting strategy (WWS) at one year [4]. A study comparing Watchful waiting strategy (WWS) and transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) in men with moderate LUTS showed the surgical group had improved bladder function (flow rates and PVR volumes), especially in those with high levels of bother; 36% of Watchful waiting strategy (WWS) patients crossed over to surgery within five years, leaving 64% doing well in the Watchful waiting strategy (WWS) group [5,6]. Increasing symptom bother and PVR volumes are the strongest predictors of Watchful waiting strategy (WWS) failure. Men with mild-to-moderate uncomplicated LUTS who are not too troubled by their symptoms are suitable for Watchful waiting strategy (WWS).

The behavioral and dietary modification for benign prostatic enlargement disease management is customary for this type of management to include the following components:

• education (about the patient’s condition); • reassurance (that cancer is not a cause of the urinary symptoms);

• periodic monitoring;

• lifestyle advice [3,4,7,8] such as:

- reduction of fluid intake at specific times aimed at reducing urinary frequency when most inconvenient (e.g., at night or when going out in public);

- avoidance/moderation of intake of caffeine or alcohol, which may have a diuretic and irritant effect, thereby increasing fluid output and enhancing frequency, urgency and nocturia;

- use of relaxed and double-voiding techniques;

- urethral milking to prevent post-micturition dribble;

- distraction techniques such as penile squeeze, breathing exercises, perineal pressure, and mental tricks to take the mind off the bladder and toilet, to help control OAB symptoms;

- bladder retraining that encourages men to hold on when they have urgency to increase their bladder capacity and the time between voids;

- reviewing the medication and optimising the time of administration or substituting drugs for others that have fewer urinary effects (these recommendations apply especially to diuretics);

- providing necessary assistance when there is impairment of dexterity, mobility, or mental state;

- treatment of constipation.

Evidence exists that self-management as part of Watchful waiting strategy (WWS) reduces both symptoms and progression [7,8]. Men randomised to three self-care management sessions in addition to standard care had better symptom improvement and QoL than men treated with standard care only, for up to a year [7]. A SR and meta-analysis found reasonable certainty in estimates that self-management intervention significantly reduced symptom severity in terms of IPSS at six months compared with usual care [9]. The reduction in IPSS score with self-management was similar to that achieved with drug therapy at six to twelve weeks. Self-management had a smaller, additional benefit at six weeks when added to drug therapy [9].

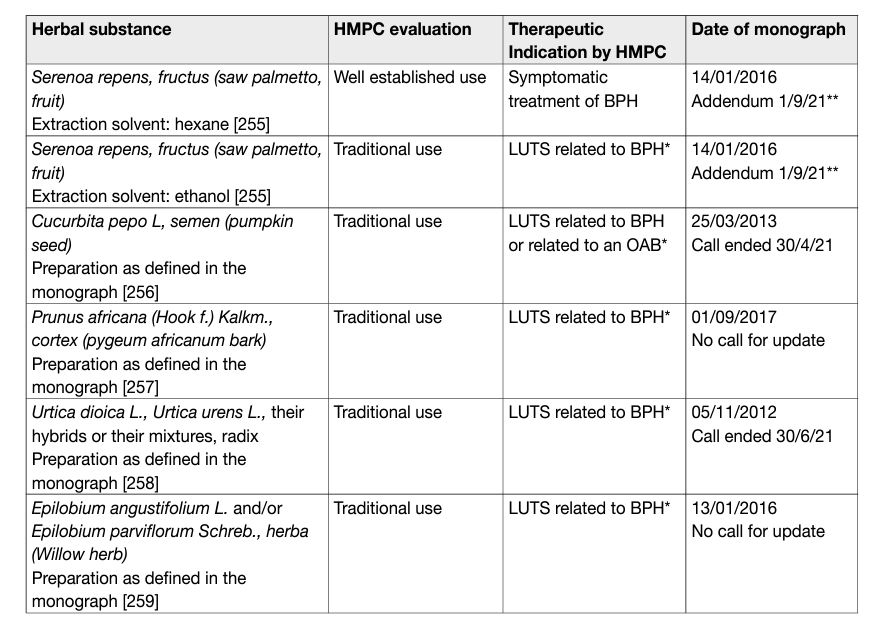

The Plant Extracts- phytotherapy with herbal medicinal products and their drug preparations are made of roots, seeds, pollen, bark, or fruits. There are single plant preparations (mono-preparations) and preparations combining two or more plants in one pill (combination preparations) [10]. Possible relevant compounds include phytosterols, ß-sitosterol, fatty acids, and lectins [10]. In vitro, plant extracts can have anti-inflammatory, anti-androgenic and oestrogenic effects; decrease sexual hormone binding globulin; inhibit aromatase, lipoxygenase, growth factor-stimulated proliferation of prostatic cells, α-adrenoceptors, 5 α-reductase, muscarinic cholinoceptors, dihydropyridine receptors and vanilloid receptors; and neutralise free radicals [10-12]. The in vivo effects of these compounds are uncertain, and the precise mechanisms of plant extracts remain unclear. The extracts of the same plant produced by different companies do not necessarily have the same biological or clinical effects; therefore, the effects of one brand cannot be extrapolated to others [13]. In addition, batches from the same producer may contain different concentrations of active ingredients [14]. A review of recent extraction techniques and their impact on the composition/biological activity of available Serenoa repens based products showed that results from different clinical trials must be compared strictly according to the same validated extraction technique and/or content of active compounds [15], as the pharmacokinetic properties of the different preparations can vary significantly. Heterogeneity and a limited regulatory framework characterise the current status of phytotherapeutic agents. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has developed the Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products (HMPC). European Union (EU) herbal monographs contain the HMPC’s scientific opinion on safety and efficacy data about herbal substances and their preparations intended for medicinal use. The HMPC evaluates all available information, including non-clinical and clinical data, whilst also documenting long-standing use and experience in the EU. European Union monographs are divided into two sections: a) Well established use (marketing authorisation): when an active ingredient of a medicine has been used for more than ten years and its efficacy and safety have been well established (including a review of the relevant literature); and b) Traditional use (simplified registration): for herbal medicinal products which do not fulfil the requirements for a marketing authorisation, but there is sufficient safety data and plausible efficacy on the basis of long-standing use and experience. Table 1 lists the available EU monographs for herbal medicinal products and the current calls for update.

Table 1: European Union monographs for herbal medicinal products

Only hexane extracted Serenoa repens (HESr) has been recommended for wellestablished use by the HMPC. Based on this a detailed scoping search covering the timeframe between the search cut-off date of the EU monograph and May 2021 was conducted for HESr. A large meta-analysis of 30 RCTs with 5,222 men and follow-up ranging from four to 60 weeks, demonstrated no benefit of treatment with S. repens in comparison to placebo for the relief of LUTS [16]. It was concluded that S. repens was not superior to placebo, finasteride, or tamsulosin with regard to IPSS improvement, Qmax, or prostate size reduction; however, the similar improvement in IPSS or Qmax compared with finasteride or tamsulosin could be interpreted as treatment equivalence. Importantly, in the meta-analysis all different brands of S. repens were included regardless or not of the presence of HESr as the main ingredient in the extract. Another SR focused on data from twelve RCTs on the efficacy and safety of (Hexan extracted serenoa repens) HESr [17]. It was concluded that HESr was superior to placebo in terms of improvement of nocturia and Qmax in patients with enlarged prostates. Improvement in LUTS was similar to tamsulosin and short-term use of finasteride. An updated SR analysed fifteen RCTs and also included twelve observational studies. It confirmed the results of the previous SR on the efficacy of HESr [18]. Compared with placebo, HESr was associated with 0.64 (95% CI: 0.98 – 0.31) fewer voids/night and an additional mean increase in Qmax of 2.75 mL/s (95% CI: 0.57 – 4.93), both were significant. When compared with α-blockers, HESr showed similar improvements in IPSS (WMD 0.57, 95% CI: 0.27 – 1.42) and a comparable increase in Qmax when compared to tamsulosin (WMD 0.02; 95% CI: 0.71 – 0.66). Efficacy assessed using IPSS was similar after six months of treatment between HESr and 5-ARIs. Analysis of all available published data for HESr showed a mean significant improvement in IPSS from baseline of 5.73 points (95% CI: 6.91 – 4.54) [18]. A network meta-analysis tried to compare the clinical efficacy of S. repens (HESr and non-HESr) against placebo and α1-blockers in men with LUTS. Interestingly, only two RCTs on HESr were included in the analysis. It was found that S. repens achieved no clinically meaningful improvement against placebo or α1-blockers in short-term follow-up. However, S. repens (Saw Palmetto) showed a clinical benefit after a prolonged period of treatment, and HESr demonstrated a greater improvement than non-HESr in terms of IPSS [19]. With respect to safety and tolerability data from the SRs showed that HESr had a favourable safety profile with gastrointestinal disorders being the most frequent adverse effects (mean incidence 3.8%) while HESr had very limited impact on sexual function.

A cross-sectional study compared the combination of HESr with silodosin to silodosin monotherapy in patients treated for at least twelve months (mean duration 13.5 months) [20]. It was reported that 69.9% of the combination therapy patients achieved the predefined clinically meaningful improvement (improvement more than three points in baseline IPSS) compared to 30.1% of patients treated only with silodosin. In addition, a greater than 25% improvement in IPSS was found in 68.8% and 31.2% of the patients in the combination and the monotherapy groups, respectively. These data suggest that combination of a α1-blocker with HESr may result in greater clinically meaningful improvements in LUTS compared to α1-blocker monotherapy [20].

The pharmacological treatment is an effective and important part in the management of the benign prostate enlargement .The combination therapy consists of an α1-blocker together with a 5-ARI. The α1-blocker exhibits clinical effects within hours or days, whereas the 5-ARI needs several months to develop full clinical efficacy. Finasteride has been tested in clinical trials with alfuzosin, terazosin, doxazosin or terazosin, and dutasteride with tamsulosin.

Long-term data (four years) from the MTOPS and CombAT studies showed that combination treatment is superior to monotherapy for symptoms and Qmax, and superior to α1-blocker alone in reducing the risk of AUR or need for surgery [21, 22, 23].

In both the MTOPS and CombAT studies, combination therapy was superior to monotherapy in preventing clinical progression as defined by an IPSS increase of at least four points, AUR, UTI, incontinence, or an increase in creatinine > 50%. The MTOPS study found that the risk of long-term clinical progression (primarily due to increasing IPSS) was reduced by 66% with combined therapy vs. placebo and to a greater extent than with either finasteride or doxazosin monotherapy (34% and 39%, respectively) [21]. In addition, finasteride (alone or in combination), but not doxazosin alone, significantly reduced both the risks of AUR and the need for BPO-related surgery over the four-year study. In the CombAT study, combination therapy reduced the relative risks of AUR by 68%, BPO-related surgery by 71%, and symptom deterioration by 41% compared with tamsulosin, after four years [24]. To prevent one case of urinary retention and/or surgical treatment thirteen patients need to be treated for four years with dutasteride and tamsulosin combination therapy compared to tamsulosin monotherapy while the absolute risk reduction (risk difference) was 7.7%.

Compared with α1-blockers or 5-ARI monotherapy, combination therapy results in a greater improvement in LUTS and increase in Qmax and is superior in prevention of disease progression. However, combination therapy is also associated with a higher rate of adverse events. Combination therapy should therefore be prescribed primarily in men who have moderate-to-severe LUTS who are at risk of disease progression (higher prostate volume, higher PSA concentration, advanced age, higher PVR, lower Qmax, etc.). Combination therapy should only be used when long-term treatment (more than twelve months) is intended, and patients should be informed of this. Discontinuation of the α1-blocker after six months might be considered in men with moderate LUTS.

The Combination treatment consists of an α1-blocker together with an antimuscarinic aiming to antagonise both α1-adrenoceptors and muscarinic receptors has been investigated with the possible combinations, but have not all been tested in clinical trials to date.

Several RCTs and prospective studies, lasting four to twelve weeks, either as an initial treatment in men with OAB and presumed BPO or as a sequential treatment for storage symptoms persisting while on an α1-blocker [25, 26, 24, 27-34]. Combination treatment is more efficacious in reducing urgency, UUI, voiding frequency, nocturia, or IPSS compared with α1-blockers or placebo alone, and improves QoL [26,34]. A SR showed that combination therapy of tolterodine and an α1-blocker was significantly more efficacious than either monotherapy for 24-hours and night voiding frequency, and 24-hours urgency episodes [26].

Effectiveness of therapy is evident primarily in those men with moderate-to-severe storage LUTS [35]. Long term use of combination therapy has been reported in patients receiving treatment for up to one year, showing symptomatic response is maintained, with a low incidence of AUR [36]. In men with moderate to-severe storage symptoms, voiding symptoms and PVR < 150 mL, the reduction in symptoms using combination therapy is associated with patient-relevant improvements in health related QoL compared with placebo and α1-blocker monotherapy [37].

Class effects are likely to underlie efficacy and QoL using an α1-blocker and antimuscarinic. Trials used mainly storage symptom endpoints, were of short duration, and included only men with low PVR volumes at baseline. Therefore, measuring PVR is recommended during combination treatment.

Combination therapy consists of an α1-blocker together with a beta-3 agonist as an add-on therapy in males receiving α1-blockers with persisting OAB symptoms.

In the MATCH study main adverse events were in line with previous trials, and cardiovascular events were uncommon in the studied populations [38]. The PLUS phase IV trial also reported adverse events similar to those seen in previous trials (hypertension, headache and nasopharyngitis being the most frequent) [39]. There were six episodes of retention recorded (1.7%) and overall, no clinically significant specific change was seen in Qmax and PVR. An open-label, randomised, 2-arm, 2-sequence study reported that the addition of mirabegron or tamsulosin to patients under tamsulosin or mirabegron monotherapy did not cause clinically relevant changes in cardiovascular safety or safety profiles [40]. Solifenacin and mirabegron were also compared in another RCT that has shown comparable efficacy but a better safety profile for mirabegron [41].

Add-on therapy with mirabegron in patients with remaining symptoms under α1-blocker therapy has been evaluated only in short-term clinical trials. The short-term benefit remains uncertain with a low effect size in urinary frequency compared to placebo, and more studies with longer follow-up are required.

REFERENCES:

1. Ball, A.J., et al. The natural history of untreated “prostatism”. Br J Urol, 1981. 53: 613. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6172172/

2. Kirby, R.S. The natural history of benign prostatic hyperplasia: what have we learned in the last decade? Urology, 2000. 56: 3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11074195/

3. Isaacs, J.T. Importance of the natural history of benign prostatic hyperplasia in the evaluation of pharmacologic intervention. Prostate Suppl, 1990. 3: 1. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1689166/

4. Netto, N.R., Jr., et al. Evaluation of patients with bladder outlet obstruction and mild international prostate symptom score followed up by watchful waiting. Urology, 1999. 53: 314. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9933046/

5. Flanigan, R.C., et al. 5-year outcome of surgical resection and watchful waiting for men with moderately symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia: a Department of Veterans Affairs cooperative study. J Urol, 1998. 160: 12. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9628595/

6. Wasson, J.H., et al. A comparison of transurethral surgery with watchful waiting for moderate symptoms of benign prostatic hyperplasia. The Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on Transurethral Resection of the Prostate. N Engl J Med, 1995. 332: 75. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7527493/

7. Brown, C.T., et al. Self management for men with lower urinary tract symptoms: randomised controlled trial. BMJ, 2007. 334: 25. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17118949/

8. Yap, T.L., et al. The impact of self-management of lower urinary tract symptoms on frequencyvolume chart measures. BJU Int, 2009. 104: 1104. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19485993/

9. Albarqouni, L., et al. Self-Management for Men With Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann Fam Med, 2021. 19: 157. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33685877/

10. Madersbacher, S., et al. Plant extracts: sense or nonsense? Curr Opin Urol, 2008. 18: 16. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18090484/

11. Buck, A.C. Is there a scientific basis for the therapeutic effects of serenoa repens in benign prostatic hyperplasia? Mechanisms of action. J Urol, 2004. 172: 1792. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15540722/

12. Levin, R.M., et al. A scientific basis for the therapeutic effects of Pygeum africanum and Serenoa repens. Urol Res, 2000. 28: 201. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10929430/

13. Habib, F.K., et al. Not all brands are created equal: a comparison of selected components of different brands of Serenoa repens extract. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis, 2004. 7: 195. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15289814/

14. Scaglione, F., et al. Comparison of the potency of different brands of Serenoa repens extract on 5alpha-reductase types I and II in prostatic co-cultured epithelial and fibroblast cells. Pharmacology, 2008. 82: 270. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18849646/

15. De Monte, C., et al. Modern extraction techniques and their impact on the pharmacological profile of Serenoa repens extracts for the treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms. BMC Urol, 2014. 14: 63. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25112532/

16. Tacklind, J., et al. Serenoa repens for benign prostatic hyperplasia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2009: CD001423. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19370565/

17. Novara, G., et al. Efficacy and Safety of Hexanic Lipidosterolic Extract of Serenoa repens (Permixon) in the Treatment of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Due to Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Eur Urol Focus, 2016. 2: 553. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28723522/

18. Vela-Navarrete, R., et al. Efficacy and safety of a hexanic extract of Serenoa repens (Permixon((R)) ) for the treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia (LUTS/BPH): systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials and observational studies. BJU Int, 2018. 122: 1049. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29694707/

19. Russo, G.I., et al. Clinical Efficacy of Serenoa repens Versus Placebo Versus Alpha-blockers for the Treatment of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms/Benign Prostatic Enlargement: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis of Randomized Placebo-controlled Clinical Trials. Eur Urol Focus, 2020. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31952967/

20. Boeri, L., et al. Clinically Meaningful Improvements in LUTS/BPH Severity in Men Treated with Silodosin Plus Hexanic Extract of Serenoa Repens or Silodosin Alone. Sci Rep, 2017. 7: 15179. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29123161/

21. McConnell, J.D., et al. The long-term effect of doxazosin, finasteride, and combination therapy on the clinical progression of benign prostatic hyperplasia. N Engl J Med, 2003. 349: 2387. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14681504/

22. Roehrborn, C.G., et al. The effects of dutasteride, tamsulosin and combination therapy on lower urinary tract symptoms in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostatic enlargement: 2-year results from the CombAT study. J Urol, 2008. 179: 616. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18082216/

23. Roehrborn, C.G., et al. The effects of combination therapy with dutasteride and tamsulosin on clinical outcomes in men with symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia: 4-year results from the CombAT study. Eur Urol, 2010. 57: 123. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19825505/

24. Athanasopoulos, A., et al. Combination treatment with an alpha-blocker plus an anticholinergic for bladder outlet obstruction: a prospective, randomized, controlled study. J Urol, 2003. 169: 2253. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12771763/

25. Baldwin, C.M., et al. Transdermal oxybutynin. Drugs, 2009. 69: 327. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19275276/

26. Gacci, M., et al. Tolterodine in the Treatment of Male LUTS. Curr Urol Rep, 2015. 16: 60. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26149965/

27. Chapple, C., et al. Tolterodine treatment improves storage symptoms suggestive of overactive bladder in men treated with alpha-blockers. Eur Urol, 2009. 56: 534. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19070418/

28. Kaplan, S.A., et al. Safety and tolerability of solifenacin add-on therapy to alpha-blocker treated men with residual urgency and frequency. J Urol, 2009. 182: 2825. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19837435/

29. Lee, J.Y., et al. Comparison of doxazosin with or without tolterodine in men with symptomatic bladder outlet obstruction and an overactive bladder. BJU Int, 2004. 94: 817. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15476515/

30. Lee, K.S., et al. Combination treatment with propiverine hydrochloride plus doxazosin controlled release gastrointestinal therapeutic system formulation for overactive bladder and coexisting benign prostatic obstruction: a prospective, randomized, controlled multicenter study. J Urol, 2005. 174: 1334. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16145414/

31. MacDiarmid, S.A., et al. Efficacy and safety of extended-release oxybutynin in combination with tamsulosin for treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms in men: randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Mayo Clin Proc, 2008. 83: 1002. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18775200/

32. Saito, H., et al. A comparative study of the efficacy and safety of tamsulosin hydrochloride (Harnal capsules) alone and in combination with propiverine hydrochloride (BUP-4 tablets) in patients with prostatic hypertrophy associated with pollakisuria and/or urinary incontinence. Jpn J Urol Surg, 1999. 12: 525.

33. Yang, Y., et al. Efficacy and safety of combined therapy with terazosin and tolteradine for patients with lower urinary tract symptoms associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia: a prospective study. Chin Med J (Engl), 2007. 120: 370. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17376305/

34. van Kerrebroeck, P., et al. Combination therapy with solifenacin and tamsulosin oral controlled absorption system in a single tablet for lower urinary tract symptoms in men: efficacy and safety results from the randomised controlled NEPTUNE trial. Eur Urol, 2013. 64: 1003. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23932438/

35. Van Kerrebroeck, P., et al. Efficacy and safety of solifenacin plus tamsulosin OCAS in men with voiding and storage lower urinary tract symptoms: results from a phase 2, dose-finding study (SATURN). Eur Urol, 2013. 64: 398. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23537687/

36. Drake, M.J., et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of single-tablet combinations of solifenacin and tamsulosin oral controlled absorption system in men with storage and voiding lower urinary tract symptoms: Results from the NEPTUNE study and NEPTUNE II open-label extension. Eur J, 2015. 67: 262. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25070148/

37. Drake, M.J., et al. Responder and health-related quality of life analyses in men with lower urinary tract symptoms treated with a fixed-dose combination of solifenacin and tamsulosin OCAS: results from the NEPTUNE study. BJU Int, 2015. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25907003/

38. Kakizaki, H., et al. Mirabegron Add-on Therapy to Tamsulosin for the Treatment of Overactive Bladder in Men with Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms: A Randomized, Placebo-controlled Study (MATCH). Eur Urol Focus, 2020. 6: 729. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31718957/

39. Kaplan, S.A., et al. Efficacy and Safety of Mirabegron versus Placebo Add-On Therapy in Men with Overactive Bladder Symptoms Receiving Tamsulosin for Underlying Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: A Randomized, Phase 4 Study (PLUS). J Urol, 2020. 203: 1163. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31895002/

40. Van Gelderen, M., et al. Absence of clinically relevant cardiovascular interaction upon add-on of mirabegron or tamsulosin to an established tamsulosin or mirabegron treatment in healthy middleaged to elderly men. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther, 2014. 52: 693. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24755125/

41. Soliman, M.G., et al. Efficacy and safety of mirabegron versus solifenacin as additional therapy for persistent OAB symptoms after tamsulosin monotherapy in men with probable BPO. World J Urol, 2020. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32869151/

Author Correspondence:

Prof. Dr. Semir A. Salim. Al Samarrai

Medical Director of Professor Al Samarrai Medical Center.

Dubai Healthcare City, Al-Razi Building 64, Block D, 2nd Floor, Suite 2018

E-mail: semiralsamarrai@hotmail.com

Tel: +97144233669