Benign Prostatic Enlargement

Management of Nocturia in men with lower urinary tract symptoms

PART 4

Comprehensive Review Article

Prof. Dr. Semir. A. Salim. Al Samarrai

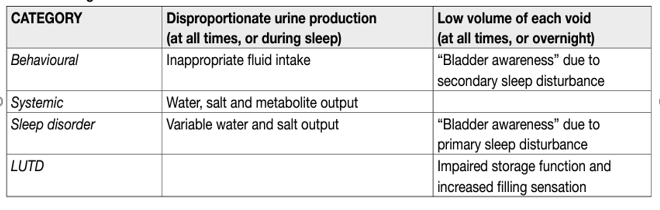

Nocturia has been defined as the complaint of waking at night to void [1]. The ICS Standardisation Steering Committee has introduced the concept of main sleep period, defined as “the period from the time of falling asleep to the time of intending to rise for the next “day” [2]. Nocturia reflects the relationship between the amount of urine produced while asleep, and the ability of the bladder to store the urine received. Nocturia can occur as part of lower urinary tract dysfunction (LUTD), such as OAB and chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Nocturia can also occur in association with other forms of LUTD, such as BOO, but here it is debated whether the link is one of causation or simply the co-existence of two common conditions. Crucially, nocturia may have behavioural, sleep disturbance (primary or secondary) or systemic causes unrelated to LUTD (Table 2). Differing causes often co-exist and each has to be considered in all cases. Only where LUTD is contributory should nocturia be termed a LUTS.

Table 1. Categories of nocturia

The golden standard treatment for Nocturia based on the antidiuretic hormone arginine vasopressin (AVP) which plays a key role in body water homeostasis and control of urine production by binding to V2 receptors in the renal collecting ducts. Arginine vasopressin increases water re-absorption and urinary osmolality, so decreasing water excretion and total urine volume. Arginine vasopressin also has V1 receptor mediated vasoconstrictive/hypertensive effects and a very short serum halflife, which makes the hormone unsuitable for treating nocturia/nocturnal polyuria. Desmopressin is a synthetic analogue of AVP with high V2 receptor affinity and no relevant V1 receptor affinity. It has been investigated for treating nocturia [3], with specific doses, titrated dosing, differing formulations, and options for route of administration. Most studies have short follow-up. Global interpretation of existing studies is difficult due to the limitations, imprecision, heterogeneity and inconsistencies of the studies. A SR of randomised or quasi-randomised trials in men with nocturia found that desmopressin may decrease the number of nocturnal voids by -0.46 compared to placebo over short-term follow-up (up to three months); over intermediate-term follow-up (three to twelve months) there was a change of -0.85 in nocturnal voids in a substantial number of participants without increase in major adverse events [4]. Another SR of comparative trials of men with nocturia as the primary presentation and LUTS including nocturia or nocturnal polyuria found that antidiuretic therapy using dose titration was more effective than placebo in relation to nocturnal voiding frequency and duration of undisturbed sleep [5]. Adverse events include headache, hyponatremia, insomnia, dry mouth, hypertension, abdominal pain, peripheral edema, and nausea. Three studies evaluating titrated-dose desmopressin in which men were included, reported seven serious adverse events in 530 patients (1.3%), with one death. There were seventeen cases of hyponatraemia (3.2%) and seven of hypertension (1.3%). Headache was reported in 53 (10%) and nausea in fifteen (2.8%) [5]. Hyponatremia is the most important concern, especially in patients > 65 years of age, with potential lifethreatening consequences. Baseline values of sodium over 130 mmol/L have been used as inclusion criteria in some research protocols. Assessment of sodium levels must be undertaken at baseline, after initiation of treatment or dose titration and during treatment. Desmopressin is not recommended in high-risk groups [5].

Desmopressin oral disintegrating tablets (ODT) have been studied separately in the sex-specific pivotal trials CS41 and CS40 in patients with nocturia [6,7]. Almost 87% of included patients had nocturnal polyuria and approximately 48% of the patients were > 65 years. The co-primary endpoints in both trials were change in number of nocturia episodes per night from baseline and at least a 33% decrease in the mean number of nocturnal voids from baseline during three months of treatment. The mean change in nocturia episodes from baseline was greater with desmopressin ODT compared to placebo (difference: women = -0.3 [95% CI: -0.5 to -0.1]; men = -0.4 [95% CI: -0.6 to -0.2]). The 33% responder rate was also greater with desmopressin ODT compared to placebo (women: 78% vs. 62%; men: 67% vs. 50%). Analysis of three published placebo-controlled trials of desmopressin ODT for nocturia showed that clinically significant hyponatraemia was more frequent in patients aged > 65 years than in those aged < 65 years in all dosage groups, including those receiving the minimum effective dose for desmopressin (11% of men aged > 65 years vs. 0% of men aged < 65 years receiving 50 mcg; 4% of women > 65 aged years vs. 2% of women aged < 65 years receiving 25 mcg). Severe hyponatraemia, defined as < 125 mmol/L serum sodium, was rare, affecting 22/1,431 (2%) patients overall [8]. Low dose desmopressin ODT has been approved in Europe, Canada and Australia for the treatment of nocturia with > 2 episodes in gender-specific low doses 50 mcg for men and 25 mcg for women; however, it initially failed to receive FDA approval, with the FDA citing uncertain benefit relative to risks as the reason. Following resubmission to the FDA in June 2018 desmopressin acetate sublingual tablet, 50 mcg for men and 25 mcg for women, was approved for the treatment of nocturia due to nocturnal polyuria in adults who awaken at least two times per night to void with a boxed warning for hyponatremia. Desmopressin acetate nasal spray is a new low-dose formulation of desmopressin and differs from other types of desmopressin formulation due to its bioavailability and route of administration. Desmopressin acetate nasal spray has been investigated in two RCTs including men and women with nocturia (over two episodes per night) and a mean age of 66 years. The average benefit of treatment relative to placebo was statistically significant but low, -0.3 and -0.2 for the 1.5 mcg and 0.75 mcg doses of desmopressin acetate, respectively. The number of patients with a reduction of more than 50% of nocturia episodes was 48.5% and 37.9%, respectively compared with 30% in the placebo group [9]. The reported adverse event rate of the studies was rather low, and the risk of hyponatremia was 1.2% and 0.9% for desmopressin acetate 1.5 mcg and 0.75 mcg, respectively. Desmopressin acetate nasal spray was approved by the FDA in 2017 for the treatment of nocturia due to nocturnal polyuria, but it is not available in Europe.

A complete medical assessment should be made, to exclude potentially nonurological underlying causes, e.g., sleep apnoea, before prescribing desmopressin in men with nocturia due to nocturnal polyuria. The optimal dose differs between patients, in men < 65 years desmopressin treatment should be initiated at a low dose (0.1 mg/day) and may be gradually increased up to a dosage of 0.4 mg/day every week until maximum efficacy is reached. Desmopressin is taken once daily before sleeping. Patients should avoid drinking fluids at least one hour before and for eight hours after dosing. Low dose desmopressin may be prescribed in patients > 65 years. In men > 65 years or older, low dose desmopressin should not be used if the serum sodium concentration is below normal: all patients should be monitored for hyponatremia. Urologists should be cautious when prescribing low-dose desmopressin in patients under-represented in trials (e.g., patients > 75 years) who may have an increased risk of hyponatremia.

The lower urinary tract dysfunction is diagnosed and considered causative of nocturia, relevant medications for storage (and voiding) LUTS may be considered. Applicable medications include; selective α1-adrenergic antagonists [10], antimuscarinics [11–13], 5-ARIs [14] and PDE5Is [15]. However, effect size of these medications is generally small, or not significantly different from placebo when used to treat nocturia [5]. Data on OAB medications (antimuscarinics, beta-3 agonist) generally had a female-predominant population. No studies specifically addressing the impact of OAB medications on nocturia in men were identified [5]. Benefits with combination therapies were not consistently observed.

Agents to promote sleep [16], diuretics [17], non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDs) [18] and phytotherapy [19] were reported as being associated with response or QoL improvement [5]. Effect size of these medications in nocturia is generally small, or not significantly different from placebo. Larger responses have been reported for some medications, but larger scale confirmatory RCTs are lacking. Agents to promote sleep do not appear to reduce nocturnal voiding frequency but may help patients return to sleep.

REFERENCES:

1. Abrams, P., et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn, 2002. 21: 167. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11857671/

2. Elsakka, A.M., et al. A prospective randomised controlled study comparing bipolar plasma vaporisation of the prostate to monopolar transurethral resection of the prostate. Arab J Urol, 2016. 14: 280. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27900218/

3. Wroclawski, M.L., et al. ‘Button type’ bipolar plasma vaporisation of the prostate compared with standard transurethral resection: A systematic review and meta-analysis of short-term outcome studies. BJU Int, 2016. 117: 662. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26299915/

4. Robert, G., et al. Bipolar plasma vaporization of the prostate: ready to replace GreenLight? A systematic review of randomized control trials. World J Urol, 2015. 33: 549. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25159871/

5. Yip, S.K., et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing the efficacy of hybrid bipolar transurethral vaporization and resection of the prostate with bipolar transurethral resection of the prostate. J Endourol, 2011. 25: 1889. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21923418/

6. Thangasamy, I.A., et al. Photoselective vaporisation of the prostate using 80-W and 120-W laser versus transurethral resection of the prostate for benign prostatic hyperplasia: a systematic review with meta-analysis from 2002 to 2012. Eur Urol, 2012. 62: 315. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22575913/

7. Bouchier-Hayes, D.M., et al. A randomized trial of photoselective vaporization of the prostate using the 80-W potassium-titanyl-phosphate laser vs transurethral prostatectomy, with a 1-year follow-up. BJU Int, 2010. 105: 964. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19912196/

8. Capitan, C., et al. GreenLight HPS 120-W laser vaporization versus transurethral resection of the prostate for the treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms due to benign prostatic hyperplasia: a randomized clinical trial with 2-year follow-up. Eur Urol, 2011. 60: 734. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21658839/

9. Skolarikos, A., et al., 80W PVP versus TURP: results of a randomized prospective study at 12 months of follow-up. , in Abstract presented at: American Urological Association annual meeting. 2008: Orlando, FL, USA.

10. Zhou, Y., et al. Greenlight high-performance system (HPS) 120-W laser vaporization versus transurethral resection of the prostate for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia: a metaanalysis of the published results of randomized controlled trials. Lasers Med Sci, 2016. 31: 485. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26868032/

11. Thomas, J.A., et al. A Multicenter Randomized Noninferiority Trial Comparing GreenLight-XPS Laser Vaporization of the Prostate and Transurethral Resection of the Prostate for the Treatment of Benign Prostatic Obstruction: Two-yr Outcomes of the GOLIATH Study. Eur Urol, 2016. 69: 94. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26283011/

12. Al-Ansari, A., et al. GreenLight HPS 120-W laser vaporization versus transurethral resection of the prostate for treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia: a randomized clinical trial with midterm follow-up. Eur Urol, 2010. 58: 349. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20605316/

13. Pereira-Correia, J.A., et al. GreenLight HPS 120-W laser vaporization vs transurethral resection of the prostate (<60 mL): a 2-year randomized double-blind prospective urodynamic investigation. BJU Int, 2012. 110: 1184.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22257240/

14. Kang, D.H., et al. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Functional Outcomes and

Complications Following the Photoselective Vaporization of the Prostate and Monopolar

Transurethral Resection of the Prostate. World J Men’s Health, 2016. 34: 110.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27574594/

15. Elmansy, H., et al. Holmium laser enucleation versus photoselective vaporization for prostatic adenoma greater than 60 ml: preliminary results of a prospective, randomized clinical trial. J Urol, 2012. 188: 216.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22591968/

16. Ghobrial, F.K., et al. A randomized trial comparing bipolar transurethral vaporization of the prostate with GreenLight laser (xps-180watt) photoselective vaporization of the prostate for treatment of small to moderate benign prostatic obstruction: outcomes after 2 years. BJU Int, 2020. 125: 144.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31621175/

17. Chung, D.E., et al. Outcomes and complications after 532 nm laser prostatectomy in anticoagulated patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol, 2011. 186: 977.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21791350/

18. Reich, O., et al. High power (80 W) potassium-titanyl-phosphate laser vaporization of the prostate in 66 high risk patients. J Urol, 2005. 173: 158.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15592063/

19. Ruszat, R., et al. Safety and effectiveness of photoselective vaporization of the prostate (PVP) in patients on ongoing oral anticoagulation. Eur Urol, 2007. 51: 1031.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16945475/

Author Correspondence:

Prof. Dr. Semir A. Salim. Al Samarrai

Medical Director of Professor Al Samarrai Medical Center.

Dubai Healthcare City, Al-Razi Building 64, Block D, 2nd Floor, Suite 2018

E-mail: semiralsamarrai@hotmail.com

Tel: +97144233669