Benign Prostatic Enlargement

Surgical Therapy

PART 3

Comprehensive Review Article

Prof. Dr. Semir. A. Salim. Al Samarrai

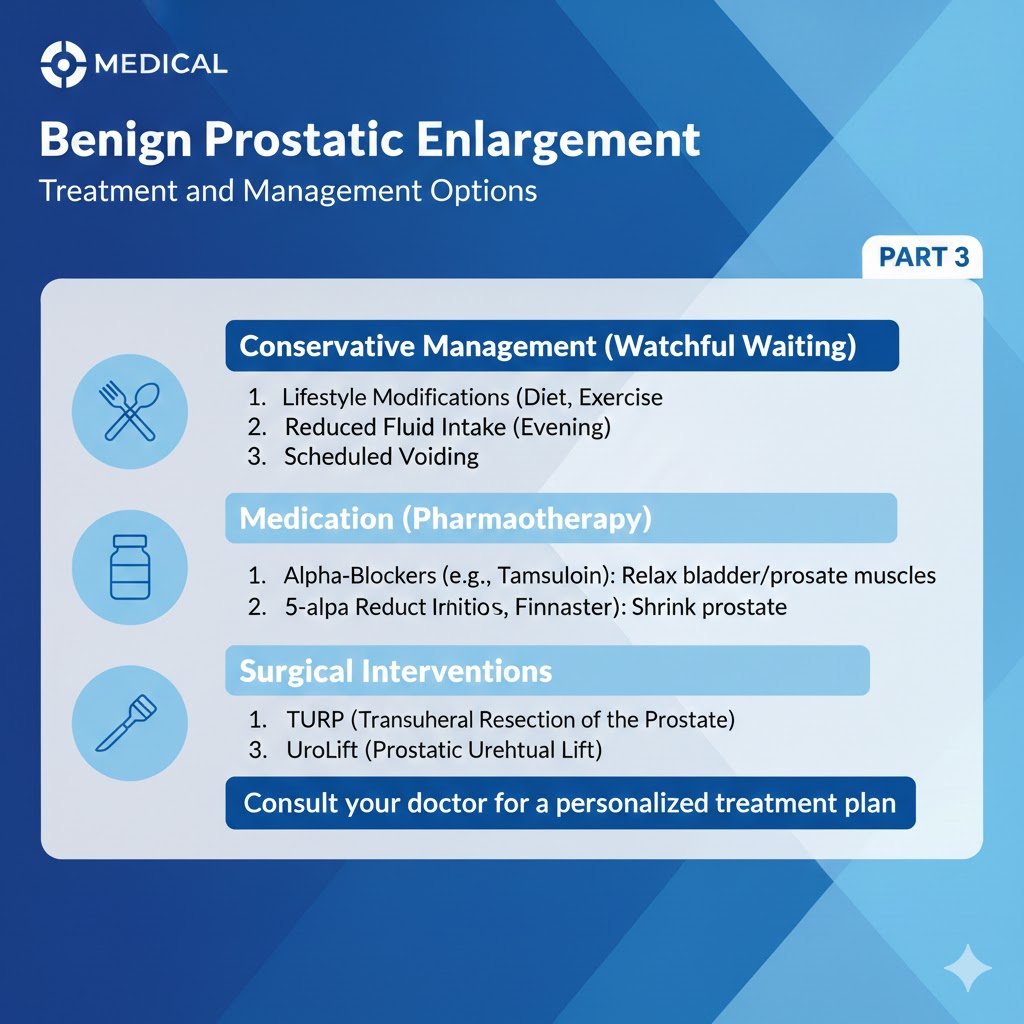

The Surgical treatment is one of the cornerstones of LUTS/BPO management. Based on its ubiquitous availability, as well as its efficacy, Monopolar-TURP has long been considered as the reference technique for the surgical management of LUTS/BPO. However, in recent years various techniques have been developed with the aim of providing a safe and effective alternative to Monopolar-TURP.

The transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) is performed using two techniques: monopolar TURP (M-TURP) and bipolar TURP (B-TURP). Monopolar transurethral resection of the prostate removes tissue from the transition zone of the gland. Bipolar TURP addresses a major limitation of M-TURP by allowing performance in normal saline. Prostatic tissue removal is identical to M-TURP. Contrary to M-TURP, in B-TURP systems, the energy does not travel through the body to reach a skin pad. Bipolar circuitry is completed locally; energy is confined between an active (resection loop) and a passive pole situated on the resectoscope tip (“true” bipolar systems) or the sheath (“quasi” bipolar systems). The various bipolar devices available differ in the way in which current flow is delivered [1,2].

Monopolar-TURP is an effective treatment for moderate-to-severe LUTS secondary to BPO. The choice should be based primarily on prostate volume (30-80 mL suitable for M-TURP). No studies on the optimal cut-off value exist, but the complication rates increase with prostate size [3]. The upper limit for M-TURP is suggested as 80 mL (based on the European Association of Urology Guidelines 2022 consensus, under the assumption that this limit depends on the surgeon’s experience, choice of resectoscope size and resection speed), as surgical duration increases, there is a significant increase in the rate of complications and the procedure is safest when performed in under 90 minutes [4]. Bipolar TURP in patients with moderate-to-severe LUTS secondary to BPO, has similar efficacy with M-TURP, but lower peri-operative morbidity. The duration of improvements with B-TURP were documented in a number of RCTs with mid-term follow-up. Long-term results (up to five years) for B-TURP showed that safety and efficacy are comparable to M-TURP [5-13]. The choice of B-TURP should be based on equipment availability, surgeon’s experience, and patient’s preference.

The holmium laser enucleation of the prostate does not play a role in contemporary treatment algorithms, because there were no relevant publications on holmium laser resection of the prostate (HoLRP) have been published since 2004, HoLRP of the prostate.

The thulium-aluminum-garnet laser (Tm:YAG) vaporization of the prostate has wavelength between 1,940 and 2,013 nm and is emitted in continuous wave mode. The laser is primarily used in front-fire applications [14]. Different applications such as vaporesection (ThuVARP) have been published [15].

As a limited number of RCTs with mid- to long-term follow-up support the efficacy of ThuVARP, there is a need for ongoing investigation of the technique.

The transurethral incision of the prostate (TUIP) involves incising the bladder outlet without tissue removal. Transurethral incision of the prostate is conventionally performed with Collins knife using monopolar electrocautery; however, alternative energy sources such as holmium laser may be used [16]. This technique may replace M-TURP in selected cases, especially in prostate sizes < 30 mL without a middle lobe.

The transurethral incision of the prostate is an effective treatment for moderate-to-severe LUTS secondary to BPO. The choice between M-TURP and TUIP should be based primarily on prostate volume (< 30 mL TUIP) [17].

The open prostatectomy is the oldest surgical treatment for moderate-to-severe LUTS secondary to BPO. Obstructive adenomas are enucleated using the index finger, approaching from within the bladder (Freyer procedure) or through the anterior prostatic capsule (Millin procedure). It is used for substantially enlarged glands (> 80-100 mL).

The open prostatectomy is the most invasive surgical method, but it is an effective and durable procedure for the treatment of LUTS/BPO. In the absence of an endourological armamentarium including a holmium laser or a bipolar system and with appropriate patient consent, OP is a reasonable surgical treatment of choice for men with prostates > 80 mL.

The bipolar transurethral enucleation of the prostate is a technology to enucleated the obstructive adenoma endoscopically by the transurethral approach. Bipolar-transurethral enucleation of the prostate (B-TUEP) evolved from plasma kinetic (PK) B-TURP and was introduced by Gyrus ACMI. The technique, also referred to as PK enucleation of the prostate (PKEP), utilises a bipolar high-frequency generator and a variety of detaching instruments, for this true bipolar system, including a point source in the form of a axipolar cystoscope electrode suitable for enucleation [18] or a resectoscope tip/resection loop [19, 20]. More recently, a novel form of B-TUEP has been described, bipolar plasma enucleation of the prostate (BPEP), stemming from B-TURP (TURis, Olympus Medical), that utilises a bipolar high frequency generator and a variety of detaching instruments including a mushroom- or button-like vapo-electrode [21,22] and a Plasmasect enucleation electrode [23] for this quasi-bipolar system. Bipolar transurethral enucleation of the prostate is followed by either morcellation [21,18] or resection [19-22, 24-26] of the enucleated adenoma.

The holmium:yttrium-aluminium garnet (Ho:YAG) laser (wavelength 2,140 nm) is a pulsed solid-state laser that is absorbed by water and water-containing tissues. Tissue coagulation and necrosis are limited to 3-4 mm, which is enough to obtain adequate haemostasis [27].

Holmium laser enucleation of the prostate requires experience and relevant endoscopic skills. The experience of the surgeon is the most important factor affecting the overall occurrence of complications [28, 29].

Enucleation using the Tm:YAG laser includes ThuVEP (vapoenucleation i.e. excising technique) and ThuLEP (blunt enucleation).

ThuLEP seems to offer similar efficacy and safety when compared to TURP, bipolar enucleation and HoLEP; whereas, ThuVEP is not supported by RCTs. Based on the limited number of RCTs there is a need for ongoing investigation of these techniques.

The term minimal invasive simple prostatectomy (MISP) includes laparoscopic simple prostatectomy (LSP) and robot-assisted simple prostatectomy (RASP). The technique for LSP was first described in 2002 [30], while the first RASP was reported in 2008 [31]. Both LSP and RASP are performed using different personalised techniques, based on the transcapsular (Millin) or transvesical (Freyer) techniques of OP.

Minimal invasive simple prostatectomy seems comparable to OP in terms of efficacy and safety, providing similar improvements in Qmax and IPSS [32]. However, most studies are of a retrospective nature. High-quality studies are needed to compare the efficacy, safety, and hospitalisation times of MISP and both OP and endoscopic methods. Long-term outcomes, learning curve and cost of MISP should also be evaluated.

The Potassium-Titanyl-Phosphate (KTP) and the lithium triborate (LBO) lasers work at a wavelength of 532 nm. Laser energy is absorbed by haemoglobin, but not by water. Vaporisation leads to immediate removal of prostatic tissue. Three “Greenlight” lasers exist, which differ not only in maximum power output, but more significantly in fibre design and the associated energy tissue interaction of each. The standard Greenlight device today is the 180-W XPS laser, but the majority of evidence is published with the former 80-W KTP or 120-W HPS (LBO) laser systems.

The AquaBeam uses the principle of hydro-dissection to ablate prostatic parenchyma while sparing collagenous structures like blood vessels and the surgical capsule. A targeted high velocity saline stream ablates prostatic tissue without the generation of thermal energy under real-time transrectal ultrasound guidance; therefore, it is truly a robotic operation. After completion of ablation haemostasis is performed with a Foley balloon catheter on light traction or diathermy or low-powered laser if necessary [33].

In a double-blind, multicentre, prospective RCT 181 patients were randomised to TURP or Aquablation [34, 35]. Mean total operative time was similar for Aquablation and TURP (33 vs. 36 minutes), but resection time was significantly lower for Aquablation (4 vs. 27 minutes). At six months patients treated with Aquablation and TURP experienced large IPSS improvements (-16.9 and -15.1, respectively). The study non-inferiority hypothesis was satisfied. Larger prostates (50-80 mL) demonstrated a more pronounced benefit. At one-year follow-up, mean IPSS reduction was 15.1 with a mean percent reduction in IPSS score of 67% for both groups. Ninety-three percent and 86.7% of patients had improvements of at least five points from baseline, respectively. No significant difference in improvement of IPSS, QoL, Qmax and reduction of PVR was reported between the groups. One TURP subject (1.5%) and three Aquablation subjects (2.6%) underwent re-TURP within one year of the study procedure [36]. At two years, improvements in IPSS and flow rate were maintained in both groups [37]. Surgical retreatment rates after twelve months for Aquablation were 1.7% and 0% for TURP. Over three years, mean IPSS improvements were 14.4 and 13.9 points in the Aquablation and TURP groups, respectively. Similarly, three-year improvements in Qmax were 11.6 and 8.2 cc/sec. There were no surgical retreatments for BPH beyond twenty months, for either Aquablation or TURP [38]. Over three years, surgical retreatments were 4.3% and 1.5% respectively. A limitation of RCTs is whether they are generalisable; however, a cohort study reported similar results in their first 118 consecutive patients [39].

During mid-term follow-up, aquablation provides non-inferior functional outcomes compared to TURP in patients with LUTS and a prostate volume between 30-80 mL. Longer term follow-up is necessary to assess the clinical value of aquablation.

Prostatic artery embolisation (PAE) can be performed as a day procedure under local anaesthesia with access through the femoral or radial arteries. Digital subtraction angiography displays arterial anatomy, and the appropriate prostatic arterial supply is selectively embolised to effect stasis in treated prostatic vessels. Different techniques have been used for PAE. Atherosclerosis, excessive tortuosity of the arterial supply and the presence of adverse collaterals are anatomical obstacles for the technical approach. Cone beam computed tomography and contrast enhanced MR angiography can help identify prostatic arteries and prevent off-target embolisation particularly in patients with challenging anatomical configurations [40,41].

A multidisciplinary team approach of urologists and radiologists is mandatory and patient selection should be done by urologists and interventional radiologists. The investigation of patients with LUTS to indicate suitability for invasive techniques should be performed by urologists only. This technically demanding procedure should only be done by an interventional radiologist with specific mentored training and expertise in PAE [42]. There are data suggesting that larger prostates have a higher chance of a superior outcome with PAE in post hoc analysis of RCTs, but larger trials are required to clarify the most suitable patients for PAE [43,44].

The Rezum system uses radiofrequency power to create thermal energy in the form of water vapour, which in turn deposits the stored thermal energy when the steam phase shifts to the liquid phase upon cell contact. The steam disperses through the tissue interstices and releases stored thermal energy onto prostatic tissue effecting cell necrosis. The procedure can be performed in an office-based setting. Usually, one to three injections are needed for each lateral lobe and one to two injections may be delivered into the median lobe.

In a multicentre RCT, 197 men were enrolled and randomised in a 2:1 ratio to treatment with water vapour energy ablation or sham treatment [45]. At three months relief of symptoms, measured by a change in IPSS and Qmax were significantly improved and maintained compared to the sham arm, although only the active treatment arm was followed up to twelve months. No relevant impact was observed on PVR. Quality of life outcome was significantly improved with a meaningful treatment response of 52% at twelve months. Further validated objective outcome measures such as BPH impact index (BPHII), Overactive Bladder Questionnaire Short Form for OAB bother, and impact on QoL and ICS Male Item Short Form Survey for male incontinence demonstrated improvement of symptoms at three months follow-up with sustained efficacy throughout the study period of twelve months. The reported two-year results in the Rezum cohort arm of the same study and the recently reported four-year results confirmed durability of the positive clinical outcome after convective water vapour energy ablation [46,47]. Surgical retreatment rate was 4.4% over four years [47]. A Cochrane review found no studies comparing convective radiofrequency water vapour thermal therapy to any other active treatment form, such as TURP [48].

Safety profile was favourable with adverse events documented to be mild-to-moderate and resolving rapidly. Preservation of erectile and ejaculatory function after convective water vapour thermal therapy was demonstrated utilising validated outcome instruments such as IIEF and Male Sexual Health Questionnaire-Ejaculation Disorder Questionnaire [45].

There are two SRs of the Rezum cohort studies. One concludes that Rezum provides improvement in BPH symptoms that exceeds established minimal clinically important difference thresholds, preserves sexual function, and is associated with low surgical retreatment rates over four years. Therefore, suggesting that it may be a valuable addition to the urological armamentarium to treat LUTS in men with BPH [49]. The other, a Cochrane review reported that the certainty of evidence ranged from moderate to very low, with study limitations and imprecision being the most common reasons for down-grading of the evidence [48]. Randomised controlled trials against a reference technique are needed to confirm the first promising clinical results and to evaluate mid- and long-term efficacy and safety of water vapour energy treatment.

The prostatic urethral lift (PUL) represents a novel minimally invasive approach under local or general anaesthesia. Encroaching lateral lobes are compressed by small permanent suture-based implants delivered under cystoscopic guidance (Urolift®) resulting in an opening of the prostatic urethra leaving a continuous anterior channel through the prostatic fossa extending from the bladder neck to the verumontanum.

There are only limited data on treating patients with an obstructed/protruding middle lobe [50]. It appears that they can be effectively treated with a variation in the standard technique, but further data are needed [50]. The effectiveness in large prostate glands has not been shown yet. Long-term studies are needed to evaluate the duration of the effect in comparison to other techniques.

The intraprostatic injections with various substances have been injected directly into the prostate in order to improve LUTS, these include Botulinum toxin-A (BoNT-A), fexapotide triflutate (NX-1207) and PRX302. The primary mechanism of action of BoNT-A is through the inhibition of neurotransmitter release from cholinergic neurons [51]. The detailed mechanisms of action for the injectables NX-1207 and PRX302 are not completely understood, but experimental data suggests apoptosis-induced atrophy of the prostate with both drugs [51].

Although experimental evidence for compounds such as PRX302 were promising for their transition to clinical use positive results from Phase II-studies have not been confirmed in Phase III-trials. Nevertheless, an RCT evaluating transperineal intraprostatic BoNT-A injection vs. TURP concluded that IPSS significantly decreased in all patients, with a non-significant difference between the arms and that the BoNT-A injection significantly maintained erectile function compared to TURP at twelve months [52]. More high-quality evidence against reference techniques is needed.

REFERENCES:

1. Issa, M.M. Technological advances in transurethral resection of the prostate: bipolar versus

monopolar TURP. J Endourol, 2008. 22: 1587.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18721041/

2. Rassweiler, J., et al. Bipolar transurethral resection of the prostate–technical modifications and early

clinical experience. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol, 2007. 16: 11.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17365673/

3. Reich, O., et al. Morbidity, mortality and early outcome of transurethral resection of the prostate: a

prospective multicenter evaluation of 10,654 patients. J Urol, 2008. 180: 246.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18499179/

4. Riedinger, C.B., et al. The impact of surgical duration on complications after transurethral resection

of the prostate: an analysis of NSQIP data. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis, 2019. 22: 303.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30385836/

5. Autorino, R., et al. Four-year outcome of a prospective randomised trial comparing bipolar

plasmakinetic and monopolar transurethral resection of the prostate. Eur Urol, 2009. 55: 922.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19185975/

6. Chen, Q., et al. Bipolar transurethral resection in saline vs traditional monopolar resection of the

prostate: results of a randomized trial with a 2-year follow-up. BJU Int, 2010. 106: 1339.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20477825/

7. Fagerstrom, T., et al. Complications and clinical outcome 18 months after bipolar and monopolar

transurethral resection of the prostate. J Endourol, 2011. 25: 1043.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21568691/

8. Geavlete, B., et al. Bipolar plasma vaporization vs monopolar and bipolar TURP-A prospective,

randomized, long-term comparison. Urology, 2011. 78: 930.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21802121/

9. Giulianelli, R., et al. Comparative randomized study on the efficaciousness of endoscopic bipolar

prostate resection versus monopolar resection technique. 3 year follow-up. Arch Ital Urol Androl,

2013. 85: 86.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23820656/

10. Mamoulakis, C., et al. Midterm results from an international multicentre randomised controlled trial

comparing bipolar with monopolar transurethral resection of the prostate. Eur Urol, 2013. 63: 667.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23102675/

11. Xie, C.Y., et al. Five-year follow-up results of a randomized controlled trial comparing bipolar

plasmakinetic and monopolar transurethral resection of the prostate. Yonsei Med J, 2012. 53: 734.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22665339/

12. Komura, K., et al. Incidence of urethral stricture after bipolar transurethral resection of the prostate

using TURis: results from a randomised trial. BJU Int, 2015. 115: 644.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24909399/

13. Kumar, N., et al. Prospective Randomized Comparison of Monopolar TURP, Bipolar TURP and

Photoselective Vaporization of the Prostate in Patients with Benign Prostatic Obstruction: 36

Months Outcome. Low Urin Tract Symptoms, 2018. 10: 17.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27168018/

14. Bach, T., et al. Laser treatment of benign prostatic obstruction: basics and physical differences. Eur

Urol, 2012. 61: 317.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22033173/

15. Xia, S.J., et al. Thulium laser versus standard transurethral resection of the prostate: a randomized

prospective trial. Eur Urol, 2008. 53: 382.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17566639/

16. Bansal, A., et al. Holmium Laser vs Monopolar Electrocautery Bladder Neck Incision for Prostates

Less Than 30 Grams: A Prospective Randomized Trial. Urology, 2016. 93: 158.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27058689/

17. Lourenco, T., et al. The clinical effectiveness of transurethral incision of the prostate: a systematic

review of randomised controlled trials. World J Urol, 2010. 28: 23.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20033744/

18. Neill, M.G., et al. Randomized trial comparing holmium laser enucleation of prostate with

plasmakinetic enucleation of prostate for treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology, 2006.

68: 1020.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17095078/

19. Li, K., et al. A Novel Modification of Transurethral Enucleation and Resection of the Prostate in

Patients With Prostate Glands Larger than 80 mL: Surgical Procedures and Clinical Outcomes.

Urology, 2018. 113: 153.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29203184/

20. Zhao, Z., et al. A prospective, randomised trial comparing plasmakinetic enucleation to standard

transurethral resection of the prostate for symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia: three-year

follow-up results. Eur Urol, 2010. 58: 752.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20800340/

21. Geavlete, B., et al. Bipolar plasma enucleation of the prostate vs open prostatectomy in large benign

prostatic hyperplasia cases – a medium term, prospective, randomized comparison. BJU Int, 2013.

111: 793.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23469933/

22. Zhang, K., et al. Plasmakinetic Vapor Enucleation of the Prostate with Button Electrode versus

Plasmakinetic Resection of the Prostate for Benign Prostatic Enlargement >90 ml: Perioperative and

3-Month Follow-Up Results of a Prospective, Randomized Clinical Trial. Urol Int, 2015. 95: 260.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26044933/

23. Wang, Z., et al. A prospective, randomised trial comparing transurethral enucleation with bipolar

system (TUEB) to monopolar resectoscope enucleation of the prostate for symptomatic benign

prostatic hyperplasia. Biomed Res, 2017. 28.

https://www.alliedacademies.org/abstract/a-prospective-randomised-trial-comparing-transurethralenucleation-

with-bipolar-system-tueb-to-monopolar-resectoscope-enucleation–7722.html

24. Ran, L., et al. Comparison of fluid absorption between transurethral enucleation and transurethral

resection for benign prostate hyperplasia. Urol Int, 2013. 91: 26.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23571450/

25. Luo, Y.H., et al. Plasmakinetic enucleation of the prostate vs plasmakinetic resection of the prostate

for benign prostatic hyperplasia: comparison of outcomes according to prostate size in 310

patients. Urology, 2014. 84: 904.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25150180/

26. Zhu, L., et al. Electrosurgical enucleation versus bipolar transurethral resection for prostates larger

than 70 ml: a prospective, randomized trial with 5-year followup. J Urol, 2013. 189: 1427.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23123549/

27. Gilling, P.J., et al. Combination holmium and Nd:YAG laser ablation of the prostate: initial clinical

experience. J Endourol, 1995. 9: 151.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7633476/

28. Elzayat, E.A., et al. Holmium laser enucleation of the prostate (HoLEP): long-term results,

reoperation rate, and possible impact of the learning curve. Eur Urol, 2007. 52: 1465.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17498867/

29. Du, C., et al. Holmium laser enucleation of the prostate: the safety, efficacy, and learning experience

in China. J Endourol, 2008. 22: 1031.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18377236/

30. Mariano, M.B., et al. Laparoscopic prostatectomy with vascular control for benign prostatic

hyperplasia. J Urol, 2002. 167: 2528.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11992078/

31. Sotelo, R., et al. Robotic simple prostatectomy. J Urol, 2008. 179: 513.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18076926/

32. Lucca, I., et al. Outcomes of minimally invasive simple prostatectomy for benign prostatic

hyperplasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Urol, 2015. 33: 563.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24879405/

33. MacRae, C., et al. How I do it: Aquablation of the prostate using the AQUABEAM system. Can

J Urol, 2016. 23: 8590.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27995858/

34. Gilling, P., et al. WATER: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Controlled Trial of Aquablation vs

Transurethral Resection of the Prostate in Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia. J Urol, 2018. 199: 1252.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29360529/

35. Kasivisvanathan, V., et al. Aquablation versus transurethral resection of the prostate: 1 year United

States – cohort outcomes. Can J Urol, 2018. 25: 9317.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29900819/

36. Gilling, P.J., et al. Randomized Controlled Trial of Aquablation versus Transurethral Resection of the

Prostate in Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: One-year Outcomes. Urology, 2019. 125: 169.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30552937/

37. Gilling, P., et al. Two-Year Outcomes After Aquablation Compared to TURP: Efficacy and Ejaculatory

Improvements Sustained. Adv Ther, 2019. 36: 1326.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31028614/

38. Gilling, P., et al. Three-year outcomes after Aquablation therapy compared to TURP: results from a

blinded randomized trial. Can J Urol, 2020. 27: 10072.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32065861/

39. Bach, T., et al. Aquablation of the prostate: single-center results of a non-selected, consecutive

patient cohort. World J Urol, 2019. 37: 1369.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30288598/

40. Abt, D., et al. Comparison of prostatic artery embolisation (PAE) versus transurethral resection of the

prostate (TURP) for benign prostatic hyperplasia: randomised, open label, non-inferiority trial. BMJ,

2018. 361: k2338.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29921613/

41. Zhang, J.L., et al. Effectiveness of Contrast-enhanced MR Angiography for Visualization of the

Prostatic Artery prior to Prostatic Arterial Embolization. Radiology, 2019: 181524.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30806596/

42. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Prostate artery embolisation for lower urinary tract

symptoms caused by benign prostatic hyperplasia. NICE Guidelines, 2018.

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ipg611

43. Desai, M., et al. Aquablation for benign prostatic hyperplasia in large prostates (80-150 mL):

6-month results from the WATER II trial. BJU Int, 2019.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30734990/

44. Abt, D., et al. Outcome prediction of prostatic artery embolization: post hoc analysis of a

randomized, open-label, non-inferiority trial. BJU Int, 2019. 124: 134.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30499637/

45. McVary, K.T., et al. Erectile and Ejaculatory Function Preserved With Convective Water Vapor

Energy Treatment of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Secondary to Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia:

Randomized Controlled Study. J Sex Med, 2016. 13: 924.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27129767/

46. Roehrborn, C.G., et al. Convective Thermal Therapy: Durable 2-Year Results of Randomized

Controlled and Prospective Crossover Studies for Treatment of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Due

to Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia. J Urol, 2017. 197: 1507.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27993667/

47. McVary, K.T., et al. Rezum Water Vapor Thermal Therapy for Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms

Associated With Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: 4-Year Results From Randomized Controlled Study.

Urology, 2019. 126: 171.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30677455/

48. Kang, T.W., et al. Convective radiofrequency water vapour thermal therapy for lower urinary tract

symptoms in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2020. 2020:

CD013251.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32212174/

49. Miller, L.E., et al. Water vapor thermal therapy for lower urinary tract symptoms secondary to benign

prostatic hyperplasia: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine, 2020. 99: e21365.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32791742/

50. Rukstalis, D., et al. Prostatic Urethral Lift (PUL) for obstructive median lobes: 12 month results of the

MedLift Study. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis, 2019. 22: 411.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30542055/

51. Magistro, G., et al. New intraprostatic injectables and prostatic urethral lift for male LUTS. Nat Rev

Urol, 2015. 12: 461.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26195444/

52. El-Dakhakhny, A.S., et al. Transperineal intraprostatic injection of botulinum neurotoxin A vs

transurethral resection of prostate for management of lower urinary tract symptoms secondary to

benign prostate hyperplasia: A prospective randomised study. Arab J Urol, 2019. 17: 270.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31723444/

Author Correspondence:

Prof. Dr. Semir A. Salim. Al Samarrai

Medical Director of Professor Al Samarrai Medical Center.

Dubai Healthcare City, Al-Razi Building 64, Block D, 2nd Floor, Suite 2018

E-mail: semiralsamarrai@hotmail.com

Tel: +97144233669