MALE INFERTILITY

The Varicocele testis and the male accessory gland infections

Comprehensive Review Article

Part 2

Prof. Dr. Semir. A. Salim. Al Samarrai

At present, the clinical management of varicocele is still mainly based on physical examination; nevertheless, scrotal colour Doppler US is useful in assessing venous reflux and diameter, when palpation is unreliable and/or in detecting recurrence/persistence after surgery [1]. Definitive evidence of reflux and venous diameter may be utilised in the decision to treat.

Scrotal US is able to detect changes in the proximal part of the seminal tract due to obstruction. Especially for CBAVD patients, scrotal US is a favourable option to detect the abnormal appearance of the epididymis. Given that, three types of epididymal findings are described in CBAVD patients: tubular ectasia (honeycomb appearance), meshwork pattern, and complete or partial absence of the epididymis [2,3].

Transrectal US:

For patients with a low seminal volume, acidic pH and severe oligozoospermia or azoospermia, in whom obstruction is suspected, scrotal and transrectal US are of clinical value in detecting CBAVD and presence or absence of the epididymis and/or seminal vesicles (SV) (e.g., abnormalities/agenesis). Likewise, transrectal US (TRUS) has an important role in assessing obstructive azoospermia (OA) secondary to CBAVD or anomalies related to the obstruction of the ejaculatory ducts, such as ejaculatory duct cysts, seminal vesicular dilatation or hypoplasia/atrophy, although retrograde ejaculation should be excluded as a differential diagnosis [1,4].

Special Conditions and Relevant Clinical Entities:

- Cryptorchidism

Cryptorchidism is the most common congenital abnormality of the male genitalia; at 1 year of age nearly 1% of all full-term male infants have cryptorchidism [5]. Approximately 30% of undescended testes are nonpalpable and may be located within the abdominal cavity. These guidelines will only deal with management of cryptorchidism in adults.

- Classification

The classification of cryptorchidism is based on the duration of the condition and the anatomical position of the testes. If the undescended testis has been identified from birth, then it is termed congenital while diagnosis of acquired cryptorchidism refers to men that have been previously noted to have testes situated within the scrotum. Cryptorchidism is categorised on whether it is bilateral or unilateral and the location of the testes (inguinal, intra-abdominal or ectopic).

- Aetiology and pathophysiology

It has been postulated that cryptorchidism may be a part of the so-called testicular dysgenesis syndrome (TDS), which is a developmental disorder of the gonads caused by environmental and/or genetic influences early in pregnancy, including exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals. Besides cryptorchidism, TDS includes hypospadias, reduced fertility, increased risk of malignancy, and Leydig/Sertoli cell dysfunction [6]. Cryptorchidism has also been linked with maternal gestational smoking [7] and premature birth [8].

Pathophysiological effects in maldescended testes:

- Degeneration of germ cells

The degeneration of germ cells in maldescended testes is apparent even after the first year of life and varies, depending on the position of the testes [9]. During the second year, the number of germ cells declines. Early treatment is therefore recommended (surgery should be performed within the subsequent year) to conserve spermatogenesis and hormone production, as well as to decrease the risk for tumours [10]. Surgical treatment is the most effective. Meta-analyses on the use of medical treatment with GnRH and hCG have demonstrated poor success rates [11,12]. It has been reported that hCG treatment may be harmful to future spermatogenesis; therefore, the Nordic Consensus Statement on treatment of undescended testes does not recommend it use on a routine basis [13]. See also the EAU Guidelines on Paediatric Urology [14]. There is increasing evidence to suggest that in unilateral undescended testis, the contralateral normal descended testis may also have structural abnormalities, including smaller volume, softer consistency and reduced markers of future fertility potential (spermatogonia/tubule ratio and dark spermatogonia) [15,16]. This implies that unilateral cryptorchidism may affect the contralateral testis and patients and parents should be counselled appropriately.

- Relationship with fertility

Semen parameters are often impaired in men with a history of cryptorchidism [17]. Early surgical treatment may have a positive effect on subsequent fertility [18]. In men with a history of unilateral cryptorchidism, paternity is almost equal (89.7%) to that in men without cryptorchidism (93.7%). In men with bilateral cryptorchidism, oligozoospermia can be found in 31% and azoospermia in 42%. In cases of bilateral cryptorchidism, the rate of paternity falls to 35-53% [19]. It is also important to screen for hypogonadism, as this is a potential long-term sequela of cryptorchidism and could contribute to impaired fertility and potential problems such as testosterone deficiency and MetS [20].

- Germ cell tumours

As a component of TDS, cryptorchidism is a risk factor for testicular cancer and is associated with testicular microcalcifications and intratubular germ cell neoplasia in situ (GCNIS), formerly known as carcinoma in situ (CIS) of the testes. In 5-10% of testicular cancers, there is a history of cryptorchidism [21]. The risk of a germ cell tumour is 3.6-7.4 times higher than in the general population and 2-6% of men with a history of cryptorchidism will develop a testicular tumour [5]. Orchidopexy performed before the onset of puberty has been reported to decrease the risk of testicular cancer [22]. However, there is evidence to suggest that even men who undergo early orchidopexy still harbour a higher risk of testicular cancer than men without cryptorchidism [23]. Therefore, all men with a history of cryptorchidism should be warned that they are at increased risk of developing testicular cancer and should perform regular testicular self-examination [24]. There is also observational study data suggesting that cryptorchidism may be a risk factor for worsening clinical stage of seminoma but this needs to be substantiated with future prospective studies [25].

Disease management:

- Hormonal treatment

Human chorionic gonadotropin or GnRH is not recommended for the treatment of cryptorchidism in adulthood. Although some studies have recommended the use of hormonal stimulation as an adjunct to orchidopexy to improve fertility preservation, there is a lack of long-term data and concerns regarding impairment to spermatogenesis with the use of these drugs [26].

- Surgical treatment

In adolescence, removal of an intra-abdominal testis (with a normal contralateral testis) can be recommended, because of the risk of malignancy [27]. In adults, with a palpable undescended testis and a normal functioning contralateral testis (i.e., biochemically eugonadal), an orchidectomy may be offered as there is evidence that the undescended testis confers a higher risk of GCNIS and future development of GCT [28] and regular testicular self-examination is not an option in these patients. In patients with unilateral undescended testis (UDT) and impaired testicular function on the contralateral testis as demonstrated by biochemical hypogonadism and/or impaired sperm production (infertility), an orchidopexy may be offered to preserve androgen production and fertility.

Germ cell malignancy and male infertility:

- Testicular germ cell cancer and reproductive function

Sperm cryopreservation is considered standard practice in patients with cancer overall, and not only in those with testicular cancer [29,30]. As such, it is important to stress that all men with cancer must be offered sperm cryopreservation prior to the therapeutic use of gonadotoxic agents or ablative surgery that may impair spermatogenesis or ejaculation (i.e., chemotherapy, radiotherapy or retroperitoneal surgery).

Men with testicular germ cell cancer (TGCT) have decreased semen quality, even before cancer treatment. Azoospermia has been observed in 5–8% of men with TGCT [31] and oligospermia in 50% [32]. Given that the average 10-year survival rate for testicular cancer is 98% and it is the most common cancer in men of reproductive potential, it is mandatory to include counselling regarding fertility preservation prior to any gonadotoxic treatment [32,33]. Semen analysis and cryopreservation are therefore recommended prior to any gonadotoxic cancer treatment and all patients should be offered cryopreservation of ejaculated sperm or sperm extracted surgically (e.g., c/mTESE) if shown to be azoospermic or severely oligozoospermic. Given that a significant number of men with testicular cancer at the time of first presentation have severe semen abnormalities (i.e., severe oligozoospermia/azoospermia) even prior to any treatment [34], it is recommended that men should undergo sperm cryopreservation prior to orchidectomy.

- Testicular microcalcification (TM)

Microcalcification inside the testicular parenchyma can be found in 0.6-9% of men referred for testicular US [35,36]. Although the true incidence of TM in the general population is unknown, it is most probably rare. Ultrasound findings of TM have been seen in men with TGCT, cryptorchidism, infertility, testicular torsion and atrophy, Klinefelter syndrome, hypogonadism, male pseudo hermaphroditism and varicocele [7]. The incidence reported seems to be higher with high-frequency US machines [37]. The relationship between TM and infertility is unclear, but may relate to testicular dysgenesis, with degenerate cells being sloughed inside an obstructed seminiferous tubule and failure of the Sertoli cells to phagocytose the debris. Subsequently, calcification with hydroxyapatite occurs. Testicular microcalcification is found in testes at risk of malignant development, with a reported incidence of TM in men with TGCT of 6-46% [38–40]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control studies indicated that the presence of TM is associated with a ~18-fold higher odds ratio for testicular cancer in infertile men (pooled OR: 18.11, 95% CI: 8.09, 40.55; p < 0.0001) [41].

Testicular microcalcification should therefore be considered pre-malignant in this setting and patients counselled accordingly. Testicular biopsies from men with TM have found a higher prevalence of GCNIS, especially in those with bilateral microcalcifications [42].

- Varicocele

Varicocele is a common congenital abnormality, that may be associated with the following andrological conditions:

• male sub-fertility;

• failure of ipsilateral testicular growth and development;

• symptoms of pain and discomfort;

• hypogonadism.

- Classification

The following classification of varicocele [43] is useful in clinical practice:

• Subclinical: not palpable or visible at rest or during Valsalva manoeuvre, but can be shown by special tests (Doppler US).

• Grade 1: palpable during Valsalva manoeuvre.

• Grade 2: palpable at rest.

• Grade 3: visible and palpable at rest.

Overall, the prevalence of varicocele in one study was 48%. Of 224 patients, 104 had unilateral and 120 had bilateral varicocele; 62 (13.30%) were grade 3, 99 (21.10%) were grade 2, and 63 (13.60%) were grade 1 [44]. Worsening semen parameters are associated with a higher grade of varicocele and age [45,46].

- Diagnostic evaluation

The diagnosis of varicocele is made by physical examination and Scrotal Doppler US is indicated if physical examination is inconclusive or semen analysis remains unsatisfactory after varicocele repair to identify persistent and recurrent varicocele [43,47]. A maximum venous diameter of > 3 mm in the upright position and during the Valsalva manoeuvre and venous reflux with a duration > 2 seconds correlate with the presence of a clinically significant varicocele [48,49]. To calculate testicular volume Lambert’s formula (V=L x W x H x 0.71) should be used, as it correlates well with testicular function in patients with infertility and/ or varicocele [50]. Patients with isolated, clinical right varicocele should be examined further for abdominal, retroperitoneal and congenital pathology and anomalies.

Basic considerations:

- Varicocele and fertility

Varicocele is present in almost 15% of the normal male population, in 25% of men with abnormal semen analysis and in 35-40% of men presenting with infertility [43,45,51,52]. The incidence of varicocele among men with primary infertility is estimated at 35–44%, whereas the incidence in men with secondary infertility is 45–81% [43,52]. The exact association between reduced male fertility and varicocele is unknown. Increased scrotal temperature, hypoxia and reflux of toxic metabolites can cause testicular dysfunction and infertility due to increased overall survival and DNA damage [52]. A meta-analysis showed that improvements in semen parameters are usually observed after surgical correction in men with abnormal parameters [53]. Varicocelectomy can also reverse sperm DNA damage and improve OS levels [51,52].

- Varicocelectomy

Varicocele repair has been a subject of debate for several decades. A meta-analysis of RCTs and observational studies in men with only clinical varicoceles has shown that surgical varicocelectomy significantly improves semen parameters in men with abnormal semen parameters, including men with NOA with hypo spermatogenesis or late maturation (spermatid) arrest on testicular pathology [51,54–57]. Pain resolution after varicocelectomy occurs in 48-90% of patients [58]. A recent systematic review has shown greater improvement in higher-grade varicoceles and this should be taken into account during patient counselling [59]. In RCTs, varicocele repair in men with a subclinical varicocele was ineffective at increasing the chances of spontaneous pregnancy [60]. Also, in randomised studies that included mainly men with normal semen parameters no benefit was found to favour treatment over observation. A Cochrane review from 2012 concluded that there is evidence to suggest that treatment of a varicocele in men from couples with otherwise unexplained subfertility may improve a couple’s chance of spontaneous pregnancy [61]. Two recent metaanalyses of RCTs comparing treatment to observation in men with a clinical varicocele, oligozoospermia and otherwise unexplained infertility, favoured treatment, with a combined OR of 2.39-4.15 (95% CI: 1.56-3.66 and 95% CI: 2.31-7.45, respectively) [57,61]. Average time to improvement in semen parameters is up to two spermatogenic cycles [62,63] with spontaneous pregnancy occurring between 6 and 12 months after varicocelectomy [64,65]. A further meta-analysis has reported that varicocelectomy may improve outcomes following ART in oligozoospermic men with an OR of 1.69 (95% CI: 0.95-3.02) [66].

- Prophylactic varicocelectomy

In adolescents with a varicocele, there is a significant risk of over-treatment because most adolescents with a varicocele have no problem achieving pregnancy later in life [67]. Prophylactic treatment is only advised in case of documented testicular growth deterioration confirmed by serial clinical or Doppler US examinations and/or abnormal semen analysis [68,69].

- Varicocelectomy and NOA

Several studies have suggested that varicocelectomy may lead to sperm appearing in the ejaculate in men with azoospermia. In one such study, microsurgical varicocelectomy in men with Non‐obstructive azoospermia (NOA) led to sperm in the ejaculate post-operatively with an increase in ensuing natural or assisted pregnancies [70].

- Varicocelectomy and hypogonadism

Evidence also suggests that men with clinical varicoceles who are hypogonadal may benefit from varicocele intervention. One meta-analysis studied the efficacy of varicocele intervention by comparing the pre-operative and post-operative serum testosterone of 712 men. The combined analysis of seven studies demonstrated that the mean post-operative serum testosterone improved by 34.3 ng/dL (95% CI: 22.57-46.04, p < 0.00001, I² = 0%) compared with their pre-operative levels. An analysis of surgery vs. untreated control results showed that mean testosterone among hypogonadic patients increased by 105.65 ng/dL (95% CI: 77.99-133.32 ng/dL), favouring varicocelectomy [71].

- Varicocelectomy for assisted reproductive technology and raised DNA fragmentation

Varicocelectomy can improve sperm DNA integrity, with a mean difference of -3.37% (95% CI: -2.65% to -4.09%) [67]. There is now increasing evidence that varicocele treatment may improve DNA fragmentation and outcomes from ART [66,67]. As a consequence, more recently it has been suggested that the indications for varicocele intervention should be expanded to include men with raised DNA fragmentation. If a patient has failed ART (e.g., failure of implantation, embryogenesis or recurrent pregnancy loss) there is an argument that if DNA damage is raised, consideration could be given to varicocele intervention after extensive counselling [72], and exclusion of other causes of raised DNA fragmentation [67,73]. The dilemma is whether varicocele treatment is indicated in men with raised DNA fragmentation and normal semen parameters.

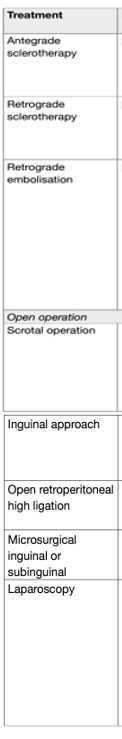

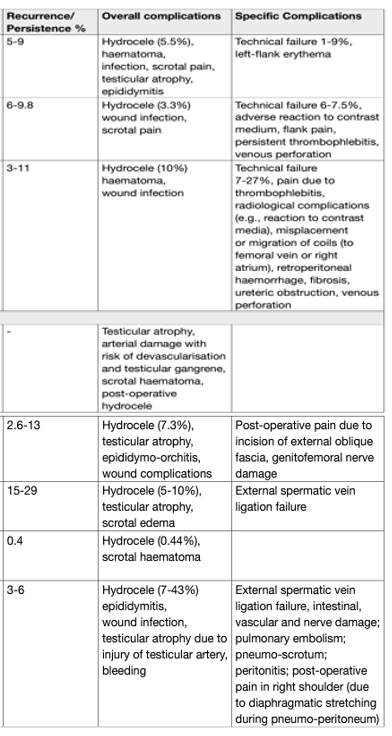

- Disease management

Several treatments are available for varicocele (Table 1). Current evidence indicates that microsurgical varicocelectomy is the most effective among the different varicocelectomy techniques [67,74]. Unfortunately, there are no large prospective RCTs comparing the efficacy of the various interventions for varicocele. However, microsurgical repair results in fewer complications and lower recurrence rates compared to the other techniques based upon case series [75]; however, this procedure requires microsurgical training. The various other techniques are still considered viable options, although recurrences and hydrocele formation appear to be higher [76]. Radiological techniques (sclerotherapy and embolisation) are minimally invasive widely used approaches, although higher recurrence rates compared to microscopic varicocelectomy have been reported (4-27%) [52]. Robot-assisted varicocelectomy has a similar success rate compared to the microscopic varicocelectomy technique, although larger prospective randomised studies are needed to establish the most effective method [77–79].

Table 1: Recurrence and complication rates associated with treatments for varicocele

Male accessory gland infections and infertility:

- Introduction

Infection of the male urogenital tract is a potentially curable cause of male infertility [80–82]. The WHO considers urethritis, prostatitis, orchitis and epididymitis to be male accessory gland infections (MAGIs) [83]. The effect of symptomatic or asymptomatic infections on sperm quality is contradictory [83]. A systematic review of the relationship between sexually transmitted infections, such as those caused by Chlamydia trachomatis, genital mycoplasmas, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Trichomonas vaginalis and viruses, and infertility was unable to draw a strong association between sexually transmitted infections and male infertility due to the limited quality of reported data [84].

Diagnostic evaluation:

- Semen analysis

Semen analysis clarifies whether the prostate is involved as part of a generalised MAGI and provides information regarding sperm quality. Leukocyte analysis allows differentiation between inflammatory and non-inflammatory chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS) (NIH IIa vs. NIH 3b National Institutes of Health classification for CP/CPPS).

- Microbiological findings

After exclusion of UTI (including urethritis), > 106 peroxidase-positive white blood-cells (WBCs) per millilitre of ejaculate indicate an inflammatory process. In these cases, a semen culture or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis should be performed for common urinary tract pathogens. A concentration of > 103 CFU/mL urinary tract pathogens in the ejaculate is indicative of significant bacteriospermia [85]. The sampling should be delivered the same day to the laboratory because the sampling time can influence the rate of positive microorganisms in semen and the frequency of isolation of different strains [86]. The ideal diagnostic test for isolating C. trachomatis in semen has not yet been established [87], but the most accurate method is PCR [88–90].

Historical data show that Ureaplasma urealyticum is pathogenic only in high concentrations (> 103 CFU/mL ejaculate). Fewer than 10% of samples analysed for Ureaplasma exceeded this concentration []. Normal colonisation of the urethra hampers the significance of mycoplasma-associated urogenital infections, using samples such as the ejaculate [92].

A meta-analysis indicated that Ureaplasma parvum and Mycoplasma genitalium were not associated with male infertility, but a significant relationship existed between U. urealyticum (OR: 3.03 95% CI: 1.02–8.99) and Mycoplasma hominis (OR: 2.8; 95% CI: 0.93– 3.64) [93].

The prevalence of human papilloma virus (HPV) in the semen ranges from 2 to 31% in the general population and is higher in men with unexplained infertility (10-35.7%) [94,95]. Recent systematic reviews have reported an association between male infertility, poorer pregnancy outcomes and semen HPV positivity [96–98]. However, data still needs to be prospectively validated to clearly define the clinical impact of HPV infection in semen. Additionally, seminal presence of Herpes Simplex virus (HSV)-2 in infertile men may be associated with lower sperm quality compared to that in HSV-negative infertile men [83]. However, it is unclear if anti-viral therapy improves fertility rates in these men.

- White blood cells

The clinical significance of an increased concentration of leukocytes in the ejaculate is controversial [99]. Although leukocytospermia is a sign of inflammation, it is not necessarily associated with bacterial or viral infections, and therefore cannot be considered a reliable indicator [100]. According to the WHO classification, leukocytospermia is defined as > 106 WBCs/mL. Only two studies have analysed alterations of WBCs in the ejaculate of patients with proven prostatitis [101,102]. Both studies found more leukocytes in men with prostatitis compared to those without inflammation (CPPS, type NIH 3b). Furthermore, leukocytospermia should be further confirmed by performing a peroxidase test on the semen. There is currently no evidence that treatment of leukocytospermia alone without evidence of infective organisms improves conception rates [103].

- Sperm quality

The deleterious effects of chronic prostatitis (CP/CPPS) on sperm density, motility and morphology have been demonstrated in a recent systematic review based on case-controlled studies [104]. Both C. trachomatis and Ureoplasma spp. can cause decreased sperm density, motility, altered morphology and increased DNA damage. Data from a recent retrospective cross-sectional study showed that U. urealyticum was the most frequent single pathogen in semen of asymptomatic infertile men; a positive semen culture was both univariably (p < 0.001) and multi-variably (p = 0.04) associated with lower sperm concentration [105]. Human papilloma virus can also induce changes in sperm density, motility and DNA damage [94,95]. Mycoplasma spp. can cause decreased motility and development of antisperm antibodies [83].

- Seminal plasma alterations

Seminal plasma elastase is a biochemical indicator of polymorphonuclear lymphocyte activity in the ejaculate [82,106,107]. Various cytokines are involved in inflammation and can influence sperm function. Several studies have investigated the association between interleukin (IL) concentration, leukocytes, and sperm function through different pathways, but no correlations have been found [108–110].

The prostate is the main site of origin of IL-6 and IL-8 in the seminal plasma. Cytokines, especially IL-6, play an important role in the male accessory gland inflammatory process [111]. However, elevated cytokine levels do not depend on the number of leukocytes in expressed prostatic secretion [112].

- Glandular secretory dysfunction

The secretory function of the prostate gland can be evaluated by measuring seminal plasma pH, citric acid, or γ-glutamine transpeptidase levels; the seminal plasma concentrations of these factors are usually altered during infection and inflammation. However, they are not recommended as diagnostic markers for MAGIs [113].

- Reactive oxygen species

Reactive oxygen species may be increased in infertile patients with asymptomatic C. trachomatis and M. hominis infection, with subsequent decrease in ROS upon antibiotic treatment. However, the levels of ROS in infertile patients with asymptomatic C. trachomatis and M. hominis in the semen are low, making it difficult to draw any firm conclusions [114]. Chronic urogenital infections are also associated with increased leukocyte numbers [115]. However, their biological significance in prostatitis remains unclear [83].

- Disease management

Treatment of CP/CPPS is usually targeted at relieving symptoms [116,117]. The indications and aims of therapy are:

• reduction or eradication of micro-organisms in prostatic secretions and semen.

• normalisation of inflammatory (e.g., leukocytes) and secretory parameters.

• improvement of sperm parameters associated with fertility impairment [118].

Only antibiotic therapy of chronic bacterial prostatitis (NIH II according to the classification) has provided symptomatic relief, eradication of micro-organisms, and a decrease in cellular and humoral inflammatory parameters in urogenital secretions. Although antibiotics might improve sperm quality [118], there is no evidence that treatment of CP/CPPS increases the probability of natural conception [82,119]. Asymptomatic presence of C. trachomatis and M. hominis in the semen can be correlated with impaired sperm quality, which recovers after antibiotic treatment. However further research is required to confirm these findings [114].

- Epididymitis

Inflammation of the epididymis causes unilateral pain and swelling, usually with acute onset. Among sexually active men aged < 35 years, epididymitis is most often caused by C. trachomatis or N. gonorrhoea [120,121]. Sexually transmitted epididymitis is usually accompanied by urethritis. Non-sexually transmitted epididymitis is associated with UTIs and occurs more often in men aged > 35 years [122].

- Diagnostic evaluation

Ejaculate analysis according to WHO Laboratory Manual for the Examination and Processing of Human Semen (6th edn) criteria, may indicate persistent inflammatory activity. Transient reductions in sperm counts and progressive motility can be observed [120,123,124]. Semen culture might help to identify pathogenic micro-organisms. Development of stenosis of the epididymal ducts, reduction of sperm count, and azoospermia are more important potential sequelae to consider in the follow-up of bilateral epididymitis.

- Disease management

Treatment of epididymitis results in:

• microbiological cure of infection.

• improvement of clinical signs and symptoms.

• prevention of potential testicular damage; • prevention of transmission.

• decrease of potential complications (e.g., infertility or chronic pain).

REFERENCES:

- Lotti, F., et al. Ultrasound of the male genital tract in relation to male reproductive health. Hum Reprod Update, 2015. 21: 56.

- Gokhale, S., et al. Epididymal Appearance in Congenital Absence of Vas Deferens. J Ultrasound Med, 2020.

- Du, J., et al. Differential diagnosis of azoospermia and etiologic classification of obstructive azoospermia: role of scrotal and transrectal US. Radiology, 2010. 256: 493.

- McQuaid, J.W., et al. Ejaculatory duct obstruction: current diagnosis and treatment. Curr Urol Rep, 2013. 14: 291.

- Berkowitz, G.S., et al. Prevalence and natural history of cryptorchidism. Pediatrics, 1993. 92: 44.

- Skakkebaek, N.E., et al. Testicular dysgenesis syndrome: an increasingly common developmental disorder with environmental aspects. Hum Reprod, 2001. 16: 972.

- Zhang, L., et al. Maternal gestational smoking, diabetes, alcohol drinking, pre-pregnancy obesity and the risk of cryptorchidism: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. PLoS One, 2015. 10: e0119006.

- Bergbrant, S., et al. Cryptorchidism in Sweden: A Nationwide Study of Prevalence, Operative Management, and Complications. J Pediatr, 2018. 194: 197.

- Gracia, J., et al. Clinical and anatomopathological study of 2000 cryptorchid testes. Br J Urol, 1995. 75: 697.

- Hadziselimovic, F., et al. Infertility in cryptorchidism is linked to the stage of germ cell development at orchidopexy. Horm Res, 2007. 68: 46.

- Bu, Q., et al. The Effectiveness of hCG and LHRH in Boys with Cryptorchidism: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Horm Metab Res, 2016. 48: 318.

- Wei, Y., et al. Efficacy and safety of human chorionic gonadotropin for treatment of cryptorchidism: A metaanalysis of randomised controlled trials. J Paediatr Child Health, 2018. 54: 900.

- Ritzén, E.M., et al. Nordic consensus on treatment of undescended testes. Acta paediatrica (Oslo, Norway : 1992), 2007. 96: 638.

- Radmayr, C., et al. EAU Guidelines on Paediatric Urology. EAU Guidelines edn. presented at EAU Annual Congress, Amsterdam 2022, 2022.

- van Brakel, J., et al. Scrotal ultrasound findings in previously congenital and acquired unilateral undescended testes and their contralateral normally descended testis. Andrology, 2015. 3: 888.

- Verkauskas, G., et al. Histopathology of Unilateral Cryptorchidism. Pediatr Dev Pathol, 2019. 22: 53.

- Yavetz, H., et al. Cryptorchidism: incidence and sperm quality in infertile men. Andrologia, 1992. 24: 293.

- Wilkerson, M.L., et al. Fertility potential: a comparison of intra-abdominal and intracanalicular testes by age groups in children. Horm Res, 2001. 55: 18.

- Lee, P.A., et al. Paternity after bilateral cryptorchidism. A controlled study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med, 1997. 151: 260.

- Rohayem, J., et al. Delayed treatment of undescended testes may promote hypogonadism and infertility. Endocrine, 2017. 55: 914.

- Giwercman, A., et al. Prevalence of carcinoma in situ and other histopathological abnormalities in testes of men with a history of cryptorchidism. J Urol, 1989. 142: 998.

- Pettersson, A., et al. Age at surgery for undescended testis and risk of testicular cancer. N Engl J Med, 2007. 356: 1835.

- Chan, E., et al. Ideal timing of orchiopexy: a systematic review. Pediatr Surg Int, 2014. 30: 87.

- Loebenstein, M., et al. Cryptorchidism, gonocyte development, and the risks of germ cell malignancy and infertility: A systematic review. J Pediatr Surg, 2019.

- Wang, X., et al. Evaluating the Effect of Cryptorchidism on Clinical Stage of Testicular Seminoma. Cancer management and research, 2020. 12: 4883.

- Radmayr, C., et al. Management of undescended testes: European Association of Urology/European Society for Paediatric Urology Guidelines. J Pediatr Urol, 2016. 12: 335.

- Bloom, D.A. Two-step orchiopexy with pelviscopic clip ligation of the spermatic vessels. J Urol, 1991. 145: 1030.

- Koni, A., et al. Histopathological evaluation of orchiectomy specimens in 51 late postpubertal men with unilateral cryptorchidism. J Urol, 2014. 192: 1183.

- Oktay, K., et al. Fertility Preservation in Patients With Cancer: ASCO Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol, 2018. 36: 1994.

- Lambertini, M., et al. Cancer and fertility preservation: international recommendations from an expert meeting. BMC Med, 2016. 14: 1.

- Petersen, P.M., et al. Semen quality and reproductive hormones before orchiectomy in men with testicular cancer. J Clin Oncol, 1999. 17: 941.

- Moody, J.A., et al. Fertility managment in testicular cancer: the need to establish a standardized and evidencebased patient-centric pathway. BJU Int, 2019. 123: 160.

- Kenney, L.B., et al. Improving Male Reproductive Health After Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancer: Progress and Future Directions for Survivorship Research. J Clin Oncol, 2018. 36: 2160.

- Giwercman, A., et al. Carcinoma in situ of the undescended testis. Semin Urol, 1988. 6: 110.

- Richenberg, J., et al. Testicular microlithiasis imaging and follow-up: guidelines of the ESUR scrotal imaging subcommittee. Eur Radiol, 2015. 25: 323.

- Pedersen, M.R., et al. Testicular microlithiasis and testicular cancer: review of the literature. Int Urol Nephrol, 2016. 48: 1079.

- Pierik, F.H., et al. Is routine scrotal ultrasound advantageous in infertile men? J Urol, 1999. 162: 1618.

- Derogee, M., et al. Testicular microlithiasis, a premalignant condition: prevalence, histopathologic findings, and relation to testicular tumor. Urology, 2001. 57: 1133.

- Miller, F.N., et al. Does testicular microlithiasis matter? A review. Clin Radiol, 2002. 57: 883.

- Giwercman, A., et al. Prevalence of carcinoma in situ and other histopathological abnormalities in testes from 399 men who died suddenly and unexpectedly. J Urol, 1991. 145: 77.

- Barbonetti, A., et al. Testicular Cancer in Infertile Men With and Without Testicular Microlithiasis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Case-Control Studies. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 2019. 10: 164.

- de Gouveia Brazao, C.A., et al. Bilateral testicular microlithiasis predicts the presence of the precursor of testicular germ cell tumors in subfertile men. J Urol, 2004. 171: 158.

- WHO, WHO Manual for the Standardized Investigation and Diagnosis of the Infertile Couple. 2000, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

- Besiroglu, H., et al. The prevalence and severity of varicocele in adult population over the age of forty years old: a cross-sectional study. Aging Male, 2019. 22: 207.

- Damsgaard, J., et al. Varicocele Is Associated with Impaired Semen Quality and Reproductive Hormone Levels: A Study of 7035 Healthy Young Men from Six European Countries. Eur Urol, 2016. 70: 1019.

- Pallotti, F., et al. Varicocele and semen quality: a retrospective case-control study of 4230 patients from a single centre. J Endocrinol Invest, 2018. 41: 185.

- Report on varicocele and infertility: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril, 2014. 102: 1556.

- Freeman, S., et al. Ultrasound evaluation of varicoceles: guidelines and recommendations of the European Society of Urogenital Radiology Scrotal and Penile Imaging Working Group (ESUR-SPIWG) for detection, classification, and grading. Eur Radiol, 2019.

- Bertolotto, M., et al. Ultrasound evaluation of varicoceles: systematic literature review and rationale of the ESURSPIWG Guidelines and Recommendations. J Ultrasound, 2020. 23: 487.

- Sakamoto, H., et al. Testicular volume measurement: comparison of ultrasonography, orchidometry, and water displacement. Urology, 2007. 69: 152.

- Baazeem, A., et al. Varicocele and male factor infertility treatment: a new meta-analysis and review of the role of varicocele repair. Eur Urol, 2011. 60: 796.

- Jensen, C.F.S., et al. Varicocele and male infertility. Nat Rev Urol, 2017. 14: 523.

- Agarwal, A., et al. Efficacy of varicocelectomy in improving semen parameters: new meta-analytical approach. Urology, 2007. 70: 532.

- Elzanaty, S. Varicocele repair in non-obstructive azoospermic men: diagnostic value of testicular biopsy – a meta-analysis. Scand J Urol, 2014. 48: 494.

- Esteves, S.C., et al. Outcome of varicocele repair in men with nonobstructive azoospermia: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Asian J Androl, 2016. 18: 246.

- Kim, H.J., et al. Clinical significance of subclinical varicocelectomy in male infertility: systematic review and meta-analysis. Andrologia, 2016. 48: 654.

- Kim, K.H., et al. Impact of surgical varicocele repair on pregnancy rate in subfertile men with clinical varicocele and impaired semen quality: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Korean J Urol, 2013. 54: 703.

- Baek, S.R., et al. Comparison of the clinical characteristics of patients with varicocele according to the presence or absence of scrotal pain. Andrologia, 2019. 51: e13187.

- Asafu-Adjei, D., et al. Systematic Review of the Impact of Varicocele Grade on Response to Surgical Management. J Urol, 2020. 203: 48.

- Yamamoto, M., et al. Effect of varicocelectomy on sperm parameters and pregnancy rate in patients with subclinical varicocele: a randomized prospective controlled study. J Urol, 1996. 155: 1636.

- Kroese, A.C., et al. Surgery or embolization for varicoceles in subfertile men. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2012. 10: CD000479.

- Machen, G.L., et al. Time to improvement of semen parameters after microscopic varicocelectomy: When it occurs and its effects on fertility. Andrologia, 2020. 52: e13500.

- Pazir, Y., et al. Determination of the time for improvement in semen parameters after varicocelectomy. Andrologia, 2020: e13895.

- Cayan, S., et al. Can varicocelectomy significantly change the way couples use assisted reproductive technologies? J Urol, 2002. 167: 1749.

- Peng, J., et al. Spontaneous pregnancy rates in Chinese men undergoing microsurgical subinguinal varicocelectomy and possible preoperative factors affecting the outcomes. Fertil Steril, 2015. 103: 635.

- Kirby, E.W., et al. Undergoing varicocele repair before assisted reproduction improves pregnancy rate and live birth rate in azoospermic and oligospermic men with a varicocele: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril, 2016. 106: 1338.

- Ding, H., et al. Open non-microsurgical, laparoscopic or open microsurgical varicocelectomy for male infertility: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BJU Int, 2012. 110: 1536.

- Locke, J.A., et al. Treatment of varicocele in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Pediatr Urol, 2017. 13: 437.

- Silay, M.S., et al. Treatment of Varicocele in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis from the European Association of Urology/European Society for Paediatric Urology Guidelines Panel. Eur Urol, 2019. 75: 448.

- Sajadi, H., et al. Varicocelectomy May Improve Results for Sperm Retrieval and Pregnancy Rate in NonObstructive Azoospermic Men. Int J Fertil Steril, 2019. 12: 303.

- Chen, X., et al. Efficacy of varicocelectomy in the treatment of hypogonadism in subfertile males with clinical varicocele: A meta-analysis. Andrologia, 2017. 49.

- Yan, S., et al. Should the current guidelines for the treatment of varicoceles in infertile men be re-evaluated? Hum Fertil (Camb), 2019: 1.

- Machen, G.L., et al. Extended indications for varicocelectomy. F1000Res, 2019. 8.

- Cayan, S., et al. Treatment of palpable varicocele in infertile men: a meta-analysis to define the best technique. J Androl, 2009. 30: 33.

- Wang, H., et al. Microsurgery Versus Laparoscopic Surgery for Varicocele: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Invest Surg, 2018: 1.

- Bryniarski, P., et al. The comparison of laparoscopic and microsurgical varicocoelectomy in infertile men with varicocoele on paternity rate 12 months after surgery: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Andrology, 2017. 5: 445.

- Etafy, M., et al. Review of the role of robotic surgery in male infertility. Arab J Urol, 2018. 16: 148.

- McCullough, A., et al. A retrospective review of single-institution outcomes with robotic-assisted microsurgical varicocelectomy. Asian J Androl, 2018. 20: 189.

- Chan, P., et al. Pros and cons of robotic microsurgery as an appropriate approach to male reproductive surgery for vasectomy reversal and varicocele repair. Fertil Steril, 2018. 110: 816.

- WHO, WHO Manual for the Standardized Investigation, Diagnosis and Management of the Infertile Male. 2000, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

- Purvis, K., et al. Infection in the male reproductive tract. Impact, diagnosis and treatment in relation to male infertility. Int J Androl, 1993. 16: 1.

- Weidner, W., et al. Relevance of male accessory gland infection for subsequent fertility with special focus on prostatitis. Hum Reprod Update, 1999. 5: 421.

- Gimenes, F., et al. Male infertility: a public health issue caused by sexually transmitted pathogens. Nat Rev Urol, 2014. 11: 672.

- Fode, M., et al. Sexually Transmitted Disease and Male Infertility: A Systematic Review. Eur Urol Focus, 2016. 2: 383.

- Rusz, A., et al. Influence of urogenital infections and inflammation on semen quality and male fertility. World J Urol, 2012. 30: 23.

- Liversedge, N.H., et al. Antibiotic treatment based on seminal cultures from asymptomatic male partners in in-vitro fertilization is unnecessary and may be detrimental. Hum Reprod, 1996. 11: 1227.

- Taylor-Robinson, D. Evaluation and comparison of tests to diagnose Chlamydia trachomatis genital infections. Hum Reprod, 1997. 12: 113.

- Khoshakhlagh, A., et al. Comparison the diagnostic value of serological and molecular methods for screening and detecting Chlamydia trachomatis in semen of infertile men: A cross-sectional study. Int J Reprod Biomed (Yazd), 2017. 15: 763.

- Páez-Canro, C., et al. Antibiotics for treating urogenital Chlamydia trachomatis infection in men and nonpregnant women. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews, 2019. 1: CD010871.

- Liang, Y., et al. Comparison of rRNA-based and DNA-based nucleic acid amplifications for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and Ureaplasma urealyticum in urogenital swabs. BMC Infect Dis, 2018. 18: 651.

- Weidner, W., et al. Ureaplasmal infections of the male urogenital tract, in particular prostatitis, and semen quality. Urol Int, 1985. 40: 5.

- Taylor-Robinson, D. Infections due to species of Mycoplasma and Ureaplasma: an update. Clin Infect Dis, 1996. 23: 671.

- Huang, C., et al. Mycoplasma and ureaplasma infection and male infertility: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Andrology, 2015. 3: 809.

- Boeri, L., et al. High-risk human papillomavirus in semen is associated with poor sperm progressive motility and a high sperm DNA fragmentation index in infertile men. Hum Reprod, 2019. 34: 209.

- Foresta, C., et al. HPV-DNA sperm infection and infertility: From a systematic literature review to a possible clinical management proposal. Andrology, 2015. 3: 163.

- Lyu, Z., et al. Human papillomavirus in semen and the risk for male infertility: a systematic review and metaanalysis. BMC Infect Dis, 2017. 17: 714.

- Xiong, Y.Q., et al. The risk of human papillomavirus infection for male fertility abnormality: a meta-analysis. Asian J Androl, 2018. 20: 493.

- Depuydt, C.E., et al. Infectious human papillomavirus virions in semen reduce clinical pregnancy rates in women undergoing intrauterine insemination. Fertil Steril, 2019. 111: 1135.

- Aitken, R.J., et al. Seminal leukocytes: passengers, terrorists or good samaritans? Hum Reprod, 1995. 10: 1736.

- Trum, J.W., et al. Value of detecting leukocytospermia in the diagnosis of genital tract infection in subfertile men. Fertil Steril, 1998. 70: 315.

- Krieger, J.N., et al. Seminal fluid findings in men with nonbacterial prostatitis and prostatodynia. J Androl, 1996. 17: 310.

- Weidner, W., et al. Semen parameters in men with and without proven chronic prostatitis. Arch Androl, 1991. 26: 173.

- Jung, J.H., et al. Treatment of Leukocytospermia in Male Infertility: A Systematic Review. World J Mens Health, 2016. 34: 165.

- Condorelli, R.A., et al. Chronic prostatitis and its detrimental impact on sperm parameters: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Endocrinol Invest, 2017.

- Boeri, L., et al. Semen infections in men with primary infertility in the real-life setting. Fertil Steril, 2020. 113: 1174.

- Wolff, H. The biologic significance of white blood cells in semen. Fertil Steril, 1995. 63: 1143.

- Wolff, H., et al. Impact of clinically silent inflammation on male genital tract organs as reflected by biochemical markers in semen. J Androl, 1991. 12: 331.

- Dousset, B., et al. Seminal cytokine concentrations (IL-1beta, IL-2, IL-6, sR IL-2, sR IL-6), semen parameters and blood hormonal status in male infertility. Hum Reprod, 1997. 12: 1476.

- Huleihel, M., et al. Distinct expression levels of cytokines and soluble cytokine receptors in seminal plasma of fertile and infertile men. Fertil Steril, 1996. 66: 135.

- Shimonovitz, S., et al. High concentration of soluble interleukin-2 receptors in ejaculate with low sperm motility. Hum Reprod, 1994. 9: 653.

- Zalata, A., et al. Evaluation of beta-endorphin and interleukin-6 in seminal plasma of patients with certain andrological diseases. Hum Reprod, 1995. 10: 3161.

- Alexander, R.B., et al. Elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines in the semen of patients with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Urology, 1998. 52: 744.

- La Vignera, S., et al. Markers of semen inflammation: supplementary semen analysis? J Reprod Immunol, 2013. 100: 2.

- Ahmadi, M.H., et al. Association of asymptomatic Chlamydia trachomatis infection with male infertility and the effect of antibiotic therapy in improvement of semen quality in infected infertile men. Andrologia, 2018.

- Depuydt, C.E., et al. The relation between reactive oxygen species and cytokines in andrological patients with or without male accessory gland infection. J Androl, 1996. 17: 699.

- Schaeffer, A.J. Clinical practice. Chronic prostatitis and the chronic pelvic pain syndrome. N Engl J Med, 2006. 355: 1690.

- Wagenlehner, F.M., et al. Chronic bacterial prostatitis (NIH type II): diagnosis, therapy and influence on the fertility status. Andrologia, 2008. 40: 100.

- Weidner, W., et al. Therapy in male accessory gland infection–what is fact, what is fiction? Andrologia, 1998. 30 Suppl 1: 87.

- Comhaire, F.H., et al. The effect of doxycycline in infertile couples with male accessory gland infection: a double-blind prospective study. Int J Androl, 1986. 9: 91.

- Berger, R., Epididymitis. In: Sexually Transmitted Diseases, in Sexually Transmitted Diseases. Holmes KK, Mardh PA, Sparling PF et al. (eds). 1984, McGraw-Hill: New York.

- Berger, R.E., et al. Etiology, manifestations and therapy of acute epididymitis: prospective study of 50 cases. J Urol, 1979. 121: 750.

- Weidner, W., et al. Acute nongonococcal epididymitis. Aetiological and therapeutic aspects. Drugs, 1987. 34 Suppl 1: 111.

- National guideline for the management of epididymo-orchitis. Clinical Effectiveness Group (Association of Genitourinary Medicine and the Medical Society for the Study of Venereal Diseases). Sex Transm Infect, 1999. 75 Suppl 1: S51.

- Weidner, W., et al., Orchitis. In: Encyclopedia of Reproduction. Knobil E, Neill JD (eds). 1999, Academic Press: San Diego.

Author Correspondence:

Prof. Dr. Semir A. Salim. Al Samarrai

Medical Director of Professor Al Samarrai Medical Center.

Dubai Healthcare City, Al-Razi Building 64, Block D, 2nd Floor, Suite 2018

E-mail: semiralsamarrai@hotmail.com

Tel: +97144233669