MALE INFERTILITY

Invasive Male Infertility Therapy of the Obstructive azoospermia (OA)

Comprehensive Review Article

Part 4

Prof. Dr. Semir. A. Salim. Al Samarrai

Obstructive azoospermia (OA):

Obstructive azoospermia (OA) is the absence of spermatozoa in the sediment of a centrifuged sample of ejaculate due to obstruction [1]. Obstructive azoospermia is less common than NOA and occurs in 20-40% of men with azoospermia [2,3]. Men with OA usually have normal FSH, testes of normal size and epididymal enlargement [4]. Of clinical relevance, men with late maturation arrest may present with normal gonadotropins and testicular size and may be only distinguished from those with OA at the time of surgical exploration. The vas deferens may be absent bilaterally (CBAVD) or unilaterally (CUAVD). Obstruction in primary infertile men is more frequently present at the epididymal level.

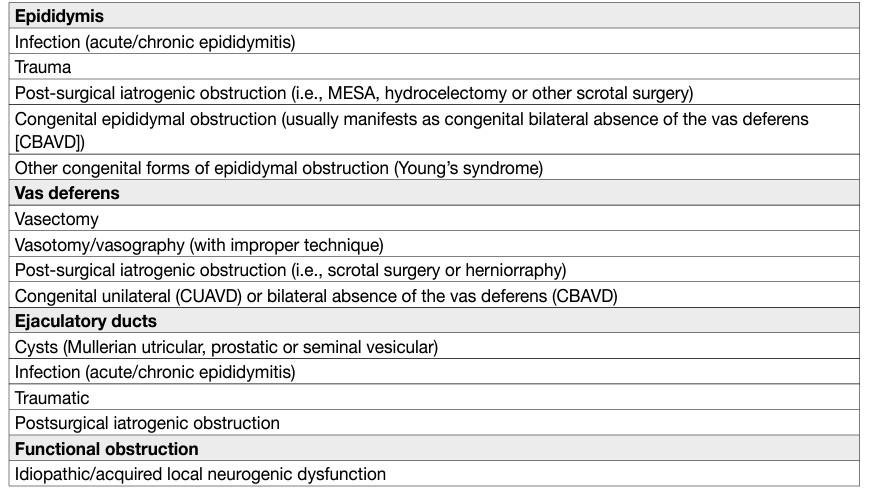

Classification of obstructive azoospermia:

Intratesticular obstruction occurs in 15% of men with OA [5]. Congenital forms are less common than acquired forms (post-inflammatory or post-traumatic) (Table 1).

Table 1: Causes of obstruction of the genitourinary system

Vas deferens obstruction:

Vas deferens obstruction is the most common cause of acquired obstruction following vasectomy [6]. Approximately 2-6% of these men request vasectomy reversal (see 2019 EAU Guidelines on Male Infertility). Vasal obstruction may also occur after hernia repair [7,8]. The most common congenital vasal obstruction is CBAVD, often accompanied by CF. Unilateral agenesis or a partial defect is associated with contralateral seminal duct anomalies or renal agenesis in 80% and 26% of cases, respectively [9].

Ejaculatory duct obstruction:

Ejaculatory duct obstruction is found in 1-5% of cases of OA and is classified as cystic or post-inflammatory or calculi of one or both ejaculatory ducts [10,11]. Cystic obstructions are usually congenital (i.e., Mullerian duct cyst or urogenital sinus/ejaculatory duct cysts) and are typically midline. In urogenital sinus abnormalities, one or both ejaculatory ducts empty into the cyst [12], while in Mullerian duct anomalies, the ejaculatory ducts are laterally displaced and compressed by the cyst [13]. Paramedian or lateral intraprostatic cysts are rare [14]. Post-inflammatory obstructions of the ejaculatory duct are usually secondary to urethra-prostatitis [15]. Congenital or acquired complete obstructions of the ejaculatory ducts are commonly associated with low seminal volume, decreased or absent seminal fructose, and acidic pH. The seminal vesicles (anterior-posterior diameter > 15 mm) and ejaculatory duct (> 2.3 mm in width) are usually dilated [11,15-17].

Functional obstruction of the distal seminal ducts:

Functional obstruction of the distal seminal ducts might be attributed to local neurogenic dysfunction [18]. This abnormality is often associated with urodynamic dysfunction. Impaired sperm transport can be observed as idiopathic or due to spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis, retroperitoneal lymph node dissection, pelvic surgery, SSRIs, α-blockers and typical antipsychotic medications [19].

Diagnostic evaluation:

- Clinical history

Clinical history-taking should follow the investigation and diagnostic evaluation of infertile men. Risk factors for obstruction include prior surgery, iatrogenic injury during inguinal herniorrhaphy, orchidopexy or hydrocelectomy.

- Clinical examination

Clinical examination should follow the guidelines for the diagnostic evaluation of infertile men. Obstructive azoospermia is indicated by at least one testis with a volume > 15 mL, although a smaller volume may be found in some patients with:

• obstructive azoospermia and concomitant partial testicular failure.

• enlarged and dilated epididymis.

• nodules in the epididymis or vas deferens. • absence or partial atresia of the vas deferens.

- Semen analysis

Azoospermia means the inability to detect spermatozoa after centrifugation at ×400 magnification. At least two semen analyses must be carried out [20,21]. When semen volume is low, a search must be made for spermatozoa in urine after ejaculation. Absence of spermatozoa and immature germ cells in the semen pellet suggest complete seminal duct obstruction.

- Hormone levels

Hormones including FSH and inhibin-B should be normal, but do not exclude other causes of testicular azoospermia (e.g., NOA). Although inhibin-B concentration is a good index of Sertoli cell integrity reflecting closely the state of spermatogenesis, its diagnostic value is no better than that of FSH and its use in clinical practice has not been widely advocated [22].

- Genetic testing

Inability to palpate one or both sides of the vas deferens should raise concern for a CFTR mutation. Any patient with unilateral or bilateral absence of the vas deferens or seminal vesicle agenesis should be offered CFTR testing [23].

- Testicular biopsy

Testicular biopsy must be combined with TESE for cryopreservation. Although studies suggest that a diagnostic or isolated testicular biopsy [24] is the most important prognostic predictor of spermatogenesis and sperm retrieval, the EAU Guidelines edition 2022 recommends not to perform testis biopsies (including fine needle aspiration [FNA]) without performing simultaneously a therapeutic sperm retrieval, as this will require a further invasive procedure after biopsy. Furthermore, even patients with extremes of spermatogenic failure (e.g., Sertoli Cell Only syndrome [SCOS]) may harbour focal areas of spermatogenesis [25,26].

Disease management:

- Intratesticular obstruction

Only TESE allows sperm retrieval in these patients and is therefore recommended.

- Epididymal obstruction

Microsurgical epididymal sperm aspiration (MESA) or percutaneous epididymal sperm aspiration (PESA) [27] is indicated in men with CBAVD. Testicular sperm extraction and percutaneous techniques, such as testicular sperm aspiration (TESA), are also options [28]. The source of sperm used for ICSI in cases of OA and the aetiology of the obstruction do not affect the outcome in terms of fertilisation, pregnancy, or miscarriage rates [29]. Usually, one MESA procedure provides sufficient material for several ICSI cycles [30] and it produces high pregnancy and fertilisation rates [31]. In patients with OA due to acquired epididymal obstruction and with a female partner with good ovarian reserve, microsurgical epididymovasostomy (EV) is recommended [32]. Epididymovasostomy can be performed with different techniques such as end-to-site and intussusception [33]. Anatomical recanalisation following surgery may require 3-18 months. A recent systematic review indicated that the time to patency in EV varies between 2.8 to 6.6 months. Reports of late failure are heterogeneous and vary between 1 and 50% [34]. Before microsurgery, and in all cases in which recanalisation is impossible, epididymal spermatozoa should be aspirated intra-operatively by MESA and cryopreserved to be used for subsequent ICSI procedures [15]. Patency rates range between 65% and 85% and cumulative pregnancy rates between 21% and 44% [35,36]. Recanalisation success rates may be adversely affected by preoperative and intra-operative findings. Robot-assisted EV has similar success rates but larger studies are needed [37].

- Vas deferens obstruction after vasectomy

Vas deferens obstruction after vasectomy requires microsurgical vasectomy reversal. The mean postprocedural patency and pregnancy rates weighted by sample size were 90-97% and 52-73%, respectively [35,36]. The average time to patency is 1.7-4.3 months and late failures are uncommon (0-12%) [34]. Robot-assisted vasovasostomy has similar success rates, and larger studies, including cost-benefit analysis, are needed to establish its benefits over standard microsurgical procedures [37]. The absence of spermatozoa in the intra-operative vas deferens fluid suggests the presence of a secondary epididymal obstruction, especially if the seminal fluid of the proximal vas deferens has a thick “toothpaste” appearance; in this case microsurgical EV may be indicated [38–40]. Simultaneous sperm retrieval may be performed for future cryopreservation and use for ICSI; likewise, patients should be counselled appropriately.

- Vas deferens obstruction at the inguinal level

It is usually impossible to correct large bilateral vas deferens defects, resulting from involuntary excision of the vasa deferentia during hernia surgery in early childhood or previous orchidopexy. In these cases, TESE/ MESA/PESA or proximal vas deferens sperm aspiration [41] can be used for cryopreservation for future ICSI. Prostate cancer patients who express an interest in future fertility should be counselled for cryopreservation [42,43].

- Ejaculatory duct obstruction

The treatment of ejaculatory duct obstruction (EDO) depends on its aetiology. Transurethral resection of the ejaculatory ducts (TURED) can be used in post-inflammatory obstruction and cystic obstruction [11,15]. Resection may remove part of the verumontanum. In cases of obstruction due to a midline intraprostatic cyst, incision, unroofing or aspiration of the cyst is required [11,15]. Intra-operative TRUS makes this procedure safer. If distal seminal tract evaluation is carried out at the time of the procedure, installation of methylene blue dye into the seminal vesicles (chromotubation) can help to confirm intra-operative opening of the ducts. Pregnancy rates after TURED are 20-25% [10,11,44]. Complications following TURED include epididymitis, UTI, gross haematuria, haematospermia, azoospermia (in cases with partial distal ejaculatory duct obstruction) and urine reflux into the ejaculatory ducts and seminal vesicles [11].

Alternative therapies for EDO include, seminal vesiculoscopy to remove debris or calculi and balloon dilation and laser incision for calcification on TRUS [45]. The alternatives to TURED are MESA, PESA, TESE, proximal vas deferens sperm aspiration and seminal vesicle-ultrasonically guided aspiration.

- Non-obstructive azoospermia

Non-obstructive azoospermia (NOA) is defined as the absence of sperm at the semen analysis after centrifugation, with usually a normal ejaculate volume. This finding should be confirmed at least at two consecutives semen analyses [46]. The severe deficit in spermatogenesis observed in NOA patients is often a consequence of primary testicular dysfunction or may be related to a dysfunction of the hypothalamuspituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis.

- Investigation of non-obstructive azoospermia

The diagnosis of NOA is based on the evidence of two consecutive semen analyses confirming azoospermia. Causes of OA should be ruled out. Patients with NOA should undergo a comprehensive assessment to identify genetically transmissible conditions, potential treatable causes of azoospermia, and potential healthrelevant co-morbidity (e.g., testicular cancer and hypogonadism [of any type]). A detailed medical history (e.g., history of cryptorchidism, previous gonadotoxic treatments for cancer, etc.) and socio-demographic characteristics [47], along with a comprehensive physical examination should be performed in every patient to detect conditions potentially leading to azoospermia, while ruling out co-morbidity frequently associated with azoospermia. Non-obstructive azoospermia can be the first sign of pituitary or germ cell tumours of the testis [48–50]. Patients with NOA have been shown to be at increased risk of being diagnosed with cancer [51]. Moreover, other systemic conditions such as MetS, T2DM, osteoporosis and CVDs have been more frequently observed in patients with NOA compared to normozoospermic men [52–54]. Azoospermic men are at higher risk of mortality [55,56]. Therefore, investigation of infertile men provides an opportunity for long-term risk stratification for other co-morbid conditions [57]. Genetic tests should be performed in patients with NOA to detect genetic abnormalities. As discussed, patients should undergo karyotype analysis [58,59], along with a screening of Y-chromosome micro-deletions [60,61] and of the gene coding for CFTR in order to exclude concomitant mutations, and to rule out CBAVD [62,63]. Genetic counselling for eventual transmissible and health-relevant genetic conditions should be provided to couples. All patients should undergo a complete hormonal investigation to exclude concomitant hypogonadism, which has been found in about 30% of patients with NOA [64,65,66]. A correct definition of the type of the associated hypogonadism (i.e., hypogonadotropic hypogonadism vs. hypergonadotropic vs. compensated hypogonadism) is relevant to differentiate diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to the patient [67]. Scrotal US may show signs of testicular dysgenesis (e.g., non-homogeneous testicular architecture and/or microcalcifications) and testicular tumours. Testicular volume may be a predictor of spermatogenic function [68] and is usually, but not invariably, low in patients with NOA. Some authors have advocated that testicular perfusion detected at US Doppler assessment can predict surgical sperm retrieval at TESE and guide testicular biopsies [69]; however, to date, data are inconsistent to suggest a routine role of testicular Doppler evaluation before TESE. In a recent multicentre study including 806 men submitted to mTESE, the size of seminiferous tubules assessed with pre-operative US was significantly associated with sperm retrieval outcomes, with a sensitivity and specificity of 76.7% and 80.7% for a cut-off point of 250 μm, respectively [70].

- Surgery for non-obstructive azoospermia

Surgical treatment for NOA is mostly aimed at retrieval of vital sperm directly from the testes (either uni- or bilaterally). This treatment is normally part of ART protocols, including IVF cycles via ICSI. Techniques and indications for surgical sperm retrieval in patients with NOA are discussed below. Any surgical approach aimed at sperm retrieval must be considered not a routine and simple biopsy; in this context, performing a diagnostic biopsy before surgery (any type) unless dedicated to ART protocols is currently considered inappropriate.

- Indications and techniques of sperm retrieval

Spermatogenesis within the testes may be focal, which means that spermatozoa can usually be found in small and isolated foci. With a wide variability among cohorts and techniques, positive SRRs have been reported in up to 50% of patients with NOA [71,72]. Numerous predictive factors for positive sperm retrieval have been investigated, although no definitive factors have been demonstrated to predict sperm retrieval [72]. Historically, there is a good correlation between the histology found at testicular biopsy and the likelihood of finding mature sperm cells during testicular sperm retrieval [24,73,74]. The presence of hypospermatogenesis at testicular biopsy showed good accuracy in predicting positive sperm retrieval after either single or multiple conventional TESE or mTESE compared with maturation arrest pattern or SCOS [24,73,74]. However, formal diagnostic biopsy is not recommended in this clinical setting for the reasons outlined above. Hormonal levels, including FSH, LH, inhibin B and AMH have been variably correlated with sperm retrieval outcomes at surgery, and data from retrospective series are still controversial [75,76-81]. Similarly, conflicting results have been published regarding testicular volume as a predictor of positive sperm retrieval [75,24,79]. Therefore, no clinical variable may be currently considered as a reliable predictor for positive sperm retrieval throughout ART patient work-up [72]. In case of complete AZFa and AZFb microdeletions, the likelihood of sperm retrieval is zero and therefore TESE procedures are contraindicated [82]. Conversely, patients with Klinefelter syndrome [83] and a history of undescended testes have been shown to have higher chance of finding sperm at surgery [79]. Historically, surgical techniques for retrieving sperm in men with NOA include testicular sperm aspiration (TESA), single or multiple conventional TESE (cTESE) and mTESE.

- Fine needle aspiration mapping

Fine needle aspiration (FNA) mapping technique has been proposed as a prognostic procedure aimed to select patients with NOA for TESE and ICSI [84]. The procedure is performed under local anaesthesia in the office and percutaneous aspiration is performed with 23G needle in multiple sites, ranging from 4 to 18 [84]. The retrieved tissue is sent for cytological and histological evaluation to provide information on the presence of mature sperm and on testicular histological pattern. Given that focal spermatogenesis may occur within the testes of patients with NOA, FNA mapping may provide information on the sites with the higher probability of retrieving sperm, thus serving as a guide for further sperm retrieval surgery in the context of ART procedures (e.g., ICSI). Turek et al. have shown that a higher number of aspiration sites may increase the chance of finding sperm [85,86]. The extent and type of subsequent sperm retrieval procedure can be tailored according to the FNA mapping results: TESA or TESE could be suggested in case of multiple positive sites for sperm, while a more precise and potentially more-invasive technique, such as mTESE, could be considered for patients with few positive sites at FNA [84]. However, no RCTs have compared the diagnostic yield from FNA and mTESE. A positive FNA requires a secondary therapeutic surgical approach, which may increase the risk of testicular damage, and without appropriate cost-benefit analysis, is not justifiable. No studies have evaluated the salvage rate of mTESE in men who have undergone FNA mapping. Therefore, FNA mapping cannot be recommended as a primary therapeutic intervention in men with NOA until further RCTs are undertaken.

- Testicular sperm aspiration

Testicular sperm aspiration (TESA) is a minimally invasive, office-based, procedure in which testicular tissue is retrieved with a biopsy needle under local anaesthesia. Reported SRRs with TESA range from 11 to 60% according to patient profile and surgical techniques [87–90]. Data have shown that using larger needles (18-21G) with multiple passes could yield a higher chance of positive sperm retrieval [90]. Complications after TESA are uncommon and mainly include minor bleeding with scrotal haematoma and post-operative pain [90]. As a less-invasive and less-costly procedure TESA has been proposed as a possible first-line approach before sending patients for a more-invasive procedure [90]. To date no RCTs have compared SRRs from TESA, cTESE and mTESE. A meta-analysis including data from case-control studies, reported that TESE was two times (95% CI: 1.8-2.2) more likely to result in successful sperm retrieval as compared with TESA [72]. Given the low success rates compared with TESE, TESA is no longer recommended in men with NOA.

- Conventional and microTESE

In patients with NOA, a testicular sperm extraction procedure is required to retrieve sperm that can be utilised in ARTs. Testicular sperm extraction was first performed through a single or multiple open biopsies of the testicle (conventional TESE [cTESE]). Conventional TESE requires a scrotal incision and open biopsy of the testes [91]. Reported SRRs in single-arm studies are about 50% [71]. Observational studies have demonstrated that multiple biopsies yield a higher chance of sperm retrieval [71,92]. In 1999, Schlegel pioneered the use of a micro testicular extraction of sperm (mTESE) approach, which utilised an operative optical microscope to inspect seminiferous tubules at a magnification of 20-25x and extract those tubules which were larger, dilated and opaque as these were more likely to harbor sperm [91]. The rationale of this technique is to increase the probability of retrieving sperm with a lower amount of tissue sampled and a subsequent lower risk of complications. A meta-analysis that pooled data analysis of case-control studies comparing cTESE with mTESE showed a lower unadjusted SRR of 35% (95% CI: 30-40) for cTESE and 52% for mTESE [72]. A more recent meta-analysis comparing cTESE and mTESE in patients with NOA showed a mean SRR of 47% (95% CI: 45;49%). No differences were observed when mTESE was compared with cTESE (46 [range 43-49] % for cTESE vs. 46 [range 42-49] % for mTESE, respectively) [93]. Meta-regression analysis demonstrated that the SRR per cycle was independent of age and hormonal parameters at enrolment. However, the SRR increased as a function of testicular volume. Retrieved sperms resulted in a live-birth rate of up to 28% per ICSI cycle [22]. The difference in surgical sperm retrieval outcomes between the two meta-analyses may be explained by the data studied [72] only one analysed case control studies whilst Corona et al. [22] also included the single randomised controlled trial), but it is important to note that all the studies comparing cTESE and mTESE have shown that the latter is superior in retrieving sperm. The probability of finding vital sperm at TESE varies also according to testicular histology: data from nonrandomised studies comparing cTESE with mTESE have shown a higher chance of sperm retrieval with mTESE only for patients with a histological diagnosis of SCOS [94]. In such cases, results ranged from 22.5 to 41% and from 6.3 to 29% for mTESE vs. cTESE, respectively [94]. Conversely, no difference between the two techniques has been found when comparing patients with a histology suggestive of maturation arrest [94]. A single study showed a small advantage of mTESE when hypospermatogenesis was found [95]. In light of these findings, some authors have advocated that cTESE could be the technique of choice in patients with a histological finding of maturation arrest or hypo-spermatogenesis [72,94]. In a study assessing the role of salvage mTESE after a previously failed cTESE or TESA, sperm were successfully retrieved in 46.5% of cases [96]. In studies reporting sperm retrieval by micro-TESE for men who had failed percutaneous testicular sperm aspiration or non-microsurgical testicular sperm extraction, the SRR was 39.1% (range 18.4-57.1%) [97,98]. Similarly, a variable SRR has been reported for salvage mTESE after a previously failed mTESE (ranging from 18.4% to 42.8%) [99,100]. Conventional TESE has been associated with a higher rate of complications compared with other techniques [71]. A total of 51.7% of patients have been found with intratesticular haematoma at scrotal US 3 months after surgery, with testicular fibrosis observed in up to 30% of patients at 6-months’ assessment [101]. A recent meta-analysis investigated the risk of hypogonadism after TESE due to testicular atrophy [102]; patients with NOA experienced a mean 2.7 nmol/L decrease in total testosterone 6 months after cTESE, which recovered to baseline within 18-26 months. Lower rates of complications have been observed with mTESE compared to cTESE, both in terms of haematoma and fibrosis [94]. Both procedures have shown a recovery of baseline testosterone levels after long-term follow-up [95,103].

- Hormonal therapy prior to surgical sperm retrieval approaches

Stimulating spermatogenesis by optimising intratesticular testosterone (ITT) has been proposed to increase the chance of sperm retrieval at the time of surgery in men with NOA. Similarly, increasing FSH serum levels could stimulate spermatogenesis. There is evidence that treatment with hCG can lead to an increase in ITT [104] and Leydig cells within the testes [105]. It has been shown in azoospermic patients with elevated gonadotropins levels that administration of hCG and/or FSH can lead to a so-called “gonadotropins reset”, with a reduction in FSH plasma concentrations and improvement in Sertoli cell’s function [106]. Similarly, clomiphene citrate may increase pituitary secretion by blocking feedback inhibition of oestradiol, thus inducing an increase in FSH and LH in patients with NOA [107]. While azoospermic patients with secondary hypogonadism should be treated accordingly to stimulate sperm production [64], no RCT has shown a benefit of hormonal treatment to enhance the chances of sperm retrieval among patients with idiopathic NOA [108]. In a large multicentre case-control study, 496 patients with idiopathic NOA treated with a combination of clomiphene, hCG and human menopausal gonadotropin according to hormonal profile, were compared with 116 controls subjected to mTESE without receiving any pre-operative treatment [107]. A total of 11% of treated patients had sperm in the ejaculate at the end of treatment; of the remaining patients, 57% had positive sperm retrieval at mTESE as compared with 33% in the control group. Likewise, in a small case-control study including 50 men with idiopathic NOA, of whom 25 were treated with recombinant FSH before mTESE, there was observed a 24% SRR compared with 12% in the control group [75]. Conversely, Gul et al. [109] failed to find any advantage of pre-operative treatment with hCG compared with no treatment, in 34 idiopathic NOA patients’ candidates for mTESE.

Hormonal therapy has been proposed to increase the chance of sperm retrieval at salvage surgery after previously failed cTESE or mTESE. Retrospective data have shown that treatment with hCG and recombinant FSH could lead to a 10-15% SRR at salvage mTESE [104,110]. In a small case-control study 28 NOA patients were treated with hCG with or without FSH for 4-5 months before salvage mTESE and compared with 20 controls subjected to salvage surgery [111]. Sperm retrieval rate was 21% in the treated group compared with 0% in the control group. The histological finding of hypo-spermatogenesis emerged as a predictor of sperm retrieval at salvage surgery after hormonal treatment [1987]. Further prospective trials are needed to elucidate the effect of hormonal treatment before salvage surgery in NOA patients, with a previously failed cTESE or mTESE. However, patients should be counselled that the evidence for the role of hormone stimulation prior to sperm retrieval surgery in men with idiopathic NOA is limited [112]. Currently, it is not recommended in routine practice.

Assisted Reproductive Technologies:

- Types of assisted reproductive technology

The assisted reproductive technology consists of procedures that involve the in vitro handling of both human oocytes and sperm, or of embryos, with the objective of establishing pregnancy [113,114]. Once couples have been prepared for treatment, the following are the steps that make up an ART cycle:

- Pharmacological stimulation of growth of multiple ovarian follicles, while at the same time other medications is given to suppress the natural menstrual cycle and down-regulate the pituitary gland.

- Careful monitoring at intervals to assess the growth of the follicles.

- Ovulation triggering: when the follicles have reached an appropriate size, a drug is administered to bring about final maturation of the eggs.

- Egg collection (usually with a trans-vaginal US probe to guide the pickup) and, in some cases of male infertility, sperm retrieval.

- Fertilisation process, which is usually completed by IVF or ICSI.

- Laboratory procedures follow for embryo culture: culture media, oxygen concentration, co-culture, assisted hatching etc.

- The embryos are placed into the uterus. Issues of importance here include endometrial preparation, the best timing for embryo transfer, how many embryos to transfer, what type of catheter to use, the use of US guidance, need for bed rest etc. Luteal phase support, for which several hormonal options are available.

Fertility treatments are complex and each cycle consists of several steps. If one of the steps is incorrectly applied, conception may not occur [113]. Several ART techniques are available:

- Intra-uterine insemination (IUI)

Intra-uterine insemination is an infertility treatment that involves the placement of the prepared sperm into the uterine cavity timed around ovulation. This can be done in combination with ovarian stimulation or in a natural cycle. The aim of the stimulation cycle is to increase the number of follicles available for fertilisation and to enhance the accurate timing of insemination in comparison to the natural cycle IUI [115–117].

Intra-uterine insemination is generally, though not exclusively, used when there is at least one patent fallopian tube with normal sperm parameters and regular ovulatory cycles (unstimulated cycles) and when the female partner is aged < 40 years. The global pregnancy rate (PR) and delivery rate (DR) for each IUI cycle with the partner’s sperm are 12.0% and 8.0%, respectively. Using donor sperm, the resultant PR and DR per cycle are 17.0% and 12.3%, respectively [118]. The rates of successful treatment cycles for patients decrease with increase in age, and the birth rates across all age groups have remained broadly stable over time. The highest birth rates have been reported in patients younger than 38 years (14% in patients aged < 35 years and 12% in those aged 35-37 years). The rates of successful treatment are low for patients older than 42 years. The multiple pregnancy rate (MPR) for IUI is ~8% [116]. Intra-uterine insemination is not recommended in couples with unexplained infertility, male factor infertility and mild endometriosis, unless the couples have religious, cultural or social objections to proceed with IVF [119]. Intra-uterine insemination with ovarian stimulation is a safer, cheaper, more patient-friendly and non-inferior alternative to IVF in the management of couples with unexplained and mild male factor infertility [115,116]. A recent RCT showed lower multiple pregnancy rates and comparable live-birth rates in patients treated with IUI with hormonal stimulation when compared to women undergoing IVF with single embryo transfer [120]. Additionally, IUI is a more cost-effective treatment than IVF for couples with unexplained or mild male subfertility [121].

- In vitro fertilisation (IVF)

Involves using controlled ovarian hyperstimulation to recruit multiple oocytes during each cycle from the female partner. Follicular development is monitored ultrasonically, and ova are harvested before ovulation with the use of US-guided needle aspiration. The recovered oocytes are mixed with processed semen to perform IVF. The developing embryos are incubated for 2-3 days in culture and then placed trans-cervically into the uterus. The rapid refinement of embryo cryopreservation methods has resulted in better perinatal outcomes of frozenthawed embryo transfer (FET) and makes it a viable alternative to fresh embryo transfer (ET) [122,123]. Frozen-thawed embryo transfer seems to be associated with lower risk of gestational complications than fresh ET. Individual approaches remain appropriate to balance the options of FET or fresh ET at present [124]. Generally, only 20%-30% of transferred embryos result in clinical pregnancies. The global PR and DR per aspiration for non-donor IVF is 24.0% and 17.6%, respectively [118]. According to the NICE guidelines, IVF treatment is appropriate in cases of unexplained infertility for women who have not conceived after 2 years of regular unprotected sexual intercourse [125].

- Intracytoplasmic sperm injection

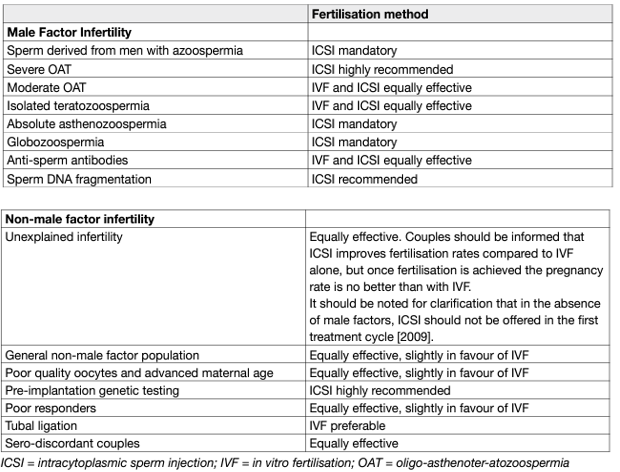

Intracytoplasmic sperm injection is a procedure through which a single sperm is injected directly into an egg using a glass micropipette. The difference between ICSI and IVF is the method used to achieve fertilisation. In conventional IVF, oocytes are incubated with sperm in a Petri dish, and the male gamete fertilises the oocyte naturally. In ICSI, the cumulus–oocyte complexes go through a denudation process in which the cumulus oophorus and corona radiata cells are removed mechanically or by an enzymatic process. This step is essential to enable microscopic evaluation of the oocyte regarding its maturity stage, as ICSI is performed only in metaphase II oocytes [126]. A thin and delicate glass micropipette (injection needle) is used to immobilise and pick up morphologically normal sperm selected for injection. A single spermatozoon is aspirated by its tail into the injection needle, which is inserted through the zona pellucida into the oocyte cytoplasm. The spermatozoon is released at a cytoplasmic site sufficiently distant from the first polar body. During this process, the oocyte is held still by a glass micropipette [126]. With this technique the oocyte can be fertilised independently of the morphology and/or motility of the spermatozoon injected. Intracytoplasmic sperm injection is currently the most commonly used ART, accounting for 70–80% of the cycles performed [127]. The procedure was first used in cases of fertilisation failure after standard IVF or when an inadequate number of sperm cells was available. The consistency of fertilisation independent of the functional quality of the spermatozoa has extended the application of ICSI to immature spermatozoa retrieved surgically from the epididymis and testis [128]. Intracytoplasmic sperm injection is the natural treatment for couples with severe male factor infertility and is also used for a number of non-male factor indications (Table2) [129].

Table 2. Fertilisation methods for male-factor and non-male factor infertility

The need to denude the oocyte allows assessment of the nuclear maturity of the oocyte. Intracytoplasmic sperm injection is also preferred in conjunction with pre-implantation genetic diagnosis and has recently been used to treat HIV discordant couples, in whom there is a pressing need to minimise exposure of the oocyte to a large number of spermatozoa [128]. The global PR and DR per aspiration for ICSI is 26.2% and 19.0%, respectively [118]. For all ages and with all the different sperm types used, fertilisation after ICSI is at approximately 70%-80% and it ensures a clinical pregnancy rate of up to 45% [127,128]. Existing evidence does not support ICSI in preference over IVF in the general non-male factor ART population; however, in couples with unexplained infertility, ICSI is associated with lower fertilisation failure rates than IVF [129]. Overall, pregnancy outcomes from ICSI are comparable between epididymal and testicular sperm and also between fresh and frozen–thawed epididymal sperm in men with OA [130]. However, these results are from studies of low evidence [129]. Sperm injection outcomes with fresh or frozen–thawed testicular sperm have been compared in men with NOA. In a meta-analysis of 11 studies and 574 ICSI cycles, no significant difference was observed between fresh and frozen–thawed testicular sperm with regards to fertilisation rate (RR: 0.97, 95% CI: 0.92–1.02) and clinical pregnancy rates (RR: 1.00, 95% CI: 0.75–1.33) [131]. However, no meta-analysis was performed on data regarding implantation, miscarriage, and low-birth rates.

- Testicular sperm in men with raised DNA fragmentation in ejaculated sperm

The use of testicular sperm for ICSI is associated with possibly improved outcomes compared with ejaculated sperm in men with high sperm DNA fragmentation [132,129]. Men with unexplained infertility with raised DNA fragmentation may be considered for TESE after failure of ART, although they should be counselled that live-birth rates are under reported in the literature and patients must weigh up the risks of performing an invasive procedure in a potentially normozoospermic or unexplained condition. The advantages of the use of testicular sperm in men with cryptozoospermia have not yet been confirmed in large scale randomised studies [133]. In terms of a practical approach, urologists may offer the use of testicular sperm in patients with high DNA fragmentation. However, patients should be counselled regarding the low levels of evidence for this (i.e., nonrandomised studies). Furthermore, testicular sperm should only be used in this setting once the common causes of oxidative stress have been excluded including varicoceles, modifications of dietary/lifestyle factors and treatment of accessory gland infections.

Safety:

The most significant risk of pre-implantation ART treatment is the ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome, a potentially life-threatening condition resulting from excessive ovarian stimulation during ART techniques, ranging from 0.6% to 5% in ART cycles [134]. Other problems include the risk of multiple pregnancies due to the transfer of more than one embryo and the associated risks to mother and baby, including multiple and preterm birth. The most prevalent maternal complications include pre-eclampsia, gestational diabetes, placenta previa, placental abruption, postpartum haemorrhage, and preterm labour and delivery [77,135,136]. The risks of foetal demise during the third trimester, perinatal mortality, preterm birth, and low birth weight increase with the number of foetuses in the pregnancy. The foetal consequences of preterm birth (cerebral palsy, retinopathy, and broncho-pulmonary dysplasia) and foetal growth restriction (polycythaemia, hypoglycaemia, and necrotising enterocolitis) are significant [137].

Analyses from the Massachusetts Outcome Study of ART reported a 50% increase (adjusted prevalence ratio of 1.5, 95% CI: 1.3–1.6) in birth defects in infants after IVF vs. spontaneous pregnancy, and a 30% increase (adjusted prevalence ratio of 1.3, 95% CI: 1.1–1.5) in birth defects in infants after subfertility vs. spontaneous pregnancy [138–140]. No difference in risk of cancer was found between ART-conceived children and those spontaneously conceived [141].

Psychosocial aspects in men’s infertility:

Male infertility impacts men’s psychological well-being in different ways. It results in emotional distress and challenges men’s sense of identity. Factors such as personality style, sociocultural background, and treatment specificities (e.g., repeated cycles, treatment side-effects), may determine men’s adjustment to infertility [142]. The effects may be particularly worst in socially isolated men, with an avoidant coping style [143]. Infertility-associated distress and psychiatric morbidity in men are further related to the male and mixed factor and increases after the clinical diagnosis [144].

LATE EFFECTS, SURVIVORSHIP AND MEN’S HEALTH:

Despite considerable public health initiatives over the past few decades, we have observed that there is still a significant gender gap between male and female in life expectancy [145]. The main contributors to male mortality in Europe are non-communicable diseases (namely CVDs, cancer, diabetes and respiratory disease) and injuries [146], as highlighted in a recent WHO report disproving the prevailing misconception that the higher rate of premature mortality among men is a natural phenomenon [145,147]. The recent pandemic situation linked with SARS-CoV-2 infection associated diseased (COVID-19) further demonstrates how the development of strategies dedicated to male health is of fundamental importance [148]. The WHO report also addresses male sexual and reproductive health which is considered under-reported, linking in particular male infertility, as a proxy for overall health, to serious diseases in men [47,52,53, 149–151]. These data suggest that health care policies should redirect their focus to preventive strategies and in particular pay attention to follow-up of men with sexual and reproductive complaints [55,152]. [152]. Considering that infertile men seem to be at greater risk of death, simply because of their inability to become fathers, is unacceptable [56].

Finally, the relationship between ED and heart disease has been firmly established for well over two decades [153,154,155, 156–159]. Cadiovascular disease is the leading cause of both male mortality and premature mortality [160–163]. Studies indicate that all major risk factors for CVD, including hypertension, smoking and elevated cholesterol are more prevalent in men than women [164–170]. Given that ED is an established early sign of atherosclerotic disease and predicts cardiovascular events as an independent factor [155], it provides urologists with the unique opportunity for CVD screening and health modification and optimise CVD risk factors, while treating men’s primary complaint (e.g., ED). Currently, both the EAU and AUA guidelines recommend screening for CVD risk factors in men with ED and late onset hypogonadism [171–173].

REFERENCES:

- WHO, WHO Manual for the Standardized Investigation, Diagnosis and Management of the Infertile Male. 2000, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

- Wosnitzer, M.S., et al. Obstructive azoospermia. Urol Clin North Am, 2014. 41: 83.

- Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine in collaboration with the Society for Male Reproduction and Urology. The management of obstructive azoospermia: a committee opinion. Feril Steril, 2019. 111: 873.

- Schoor, R.A., et al. The role of testicular biopsy in the modern management of male infertility. J Urol, 2002. 167: 197.

- Hendry, W., Azoospermia and surgery for testicular obstruction. In: Male Infertility, Hargreave TB (ed). 1997, Springer Verlag: Berlin.

- Schoysman, R. Vaso-epididymostomy–a survey of techniques and results with considerations of delay of appearance of spermatozoa after surgery. Acta Eur Fertil, 1990. 21: 239.

- Goldstein, M. Treatment of large vasal defects. In: Surgery of Male Infertility. Goldstein M (ed). 1995.

- Shin, D., et al. Herniorrhaphy with polypropylene mesh causing inguinal vasal obstruction: a preventable cause of obstructive azoospermia. Ann Surg, 2005. 241: 553.

- Schlegel, P.N., et al. Urogenital anomalies in men with congenital absence of the vas deferens. J Urol, 1996. 155: 1644.

- Moody, J.A., et al. Fertility managment in testicular cancer: the need to establish a standardized and evidencebased patient-centric pathway. BJU Int, 2019. 123: 160.

- Avellino, G.J., et al. Transurethral resection of the ejaculatory ducts: etiology of obstruction and surgical treatment options. Fertil Steril, 2019. 111: 427.

- Elder, J.S., et al. Cyst of the ejaculatory duct/urogenital sinus. J Urol, 1984. 132: 768.

- Schuhrke, T.D., et al. Prostatic utricle cysts (mullerian duct cysts). J Urol, 1978. 119: 765.

- Surya, B.V., et al. Cysts of the seminal vesicles: diagnosis and management. Br J Urol, 1988. 62: 491.

- Schroeder-Printzen, I., et al. Surgical therapy in infertile men with ejaculatory duct obstruction: technique and outcome of a standardized surgical approach. Hum Reprod, 2000. 15: 1364.

- Engin, G., et al. Transrectal US and endorectal MR imaging in partial and complete obstruction of the seminal duct system. A comparative study. Acta Radiol, 2000. 41: 288.

- Kuligowska, E., et al. Male infertility: role of transrectal US in diagnosis and management. Radiology, 1992. 185: 353.

- Colpi, G.M., et al. Functional voiding disturbances of the ampullo-vesicular seminal tract: a cause of male infertility. Acta Eur Fertil, 1987. 18: 165.

- Font, M.D., et al. An infertile male with dilated seminal vesicles due to functional obstruction. Asian J Androl, 2017. 19: 256.

- WHO, WHO Manual for the Standardized Investigation, Diagnosis and Management of the Infertile Male. 2000.

- Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine Diagnostic evaluation of the infertile male: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril, 2015. 103: e18.

- Adamopoulos, D.A., et al. ‘Value of FSH and inhibin-B measurements in the diagnosis of azoospermia’–a clinician’s overview. Int J Androl, 2010. 33: e109.

- Radpour, R., et al. Genetic investigations of CFTR mutations in congenital absence of vas deferens, uterus, and vagina as a cause of infertility. J Androl, 2008. 29: 506.

- Abdel Raheem, A., et al. Testicular histopathology as a predictor of a positive sperm retrieval in men with nonobstructive azoospermia. BJU Int, 2013. 111: 492.

- Kalsi, J., et al. In the era of micro-dissection sperm retrieval (m-TESE) is an isolated testicular biopsy necessary in the management of men with non-obstructive azoospermia? BJU Int, 2012. 109: 418.

- Kalsi JS, et al. Salvage microdissection testicular sperm extraction; outcome in men with Non obstructive azoospermia. BJU International, 2011.

- Silber, S.J., et al. Pregnancy with sperm aspiration from the proximal head of the epididymis: a new treatment for congenital absence of the vas deferens. Fertil Steril, 1988. 50: 525.

- Esteves, S.C., et al. Sperm retrieval techniques for assisted reproduction. Int Braz J Urol, 2011. 37: 570.

- Esteves, S.C., et al. Reproductive potential of men with obstructive azoospermia undergoing percutaneous sperm retrieval and intracytoplasmic sperm injection according to the cause of obstruction. J Urol, 2013. 189: 232.

- Schroeder-Printzen, I., et al. Microsurgical epididymal sperm aspiration: aspirate analysis and straws available after cryopreservation in patients with non-reconstructable obstructive azoospermia. MESA/TESE Group Giessen. Hum Reprod, 2000. 15: 2531.

- Van Peperstraten, A., et al. Techniques for surgical retrieval of sperm prior to ICSI for azoospermia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2006: Cd002807.

- Yoon, Y.E., et al. The role of vasoepididymostomy for treatment of obstructive azoospermia in the era of in vitro fertilization: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Asian J Androl, 2018.

- Peng, J., et al. Pregnancy and live birth rates after microsurgical vasoepididymostomy for azoospermic patients with epididymal obstruction. Hum Reprod, 2017. 32: 284.

- Farber, N.J., et al. The Kinetics of Sperm Return and Late Failure Following Vasovasostomy or Vasoepididymostomy: A Systematic Review. J Urol, 2019. 201: 241.

- Matthews, G.J., et al. Patency following microsurgical vasoepididymostomy and vasovasostomy: temporal considerations. J Urol, 1995. 154: 2070.

- Kolettis, P.N., et al. Vasoepididymostomy for vasectomy reversal: a critical assessment in the era of intracytoplasmic sperm injection. J Urol, 1997. 158: 467.

- Etafy, M., et al. Review of the role of robotic surgery in male infertility. Arab J Urol, 2018. 16: 148.

- Ramasamy, R., et al. Microscopic visualization of intravasal spermatozoa is positively associated with patency after bilateral microsurgical vasovasostomy. Andrology, 2015. 3: 532.

- Ostrowski, K.A., et al. Impact on Pregnancy of Gross and Microscopic Vasal Fluid during Vasectomy Reversal. J Urol, 2015. 194: 156.

- Scovell, J.M., et al. Association between the presence of sperm in the vasal fluid during vasectomy reversal and postoperative patency: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Urology, 2015. 85: 809.

- Ruiz-Romero, J., et al. A new device for microsurgical sperm aspiration. Andrologia, 1994. 26: 119.

- Tran, S., et al. Review of the Different Treatments and Management for Prostate Cancer and Fertility. Urology, 2015. 86: 936.

- Salonia, A., et al. Sperm banking is of key importance in patients with prostate cancer. Fertil Steril, 2013. 100: 367.

- Hayden, R. et al. Detection and Management of Obstructive Azoospermia. Urol Pract, 2015. 2: 33.

- Jiang, H.T., et al. Multiple advanced surgical techniques to treat acquired seminal duct obstruction. Asian J Androl, 2014. 16: 912.

- WHO. WHO laboratory manual for the examination and processing of human semen Sixth edition. 2021.

- Kasman, A.M., et al. Male Infertility and Future Cardiometabolic Health: Does the Association Vary by Sociodemographic Factors? Urology, 2019.

- Ozturk, H., et al. Asymptomatic Sertoli cell tumour diagnosed during azoospermia work-up. Asian J Androl, 2013. 15: 845.

- Fallick, M.L., et al. Leydig cell tumors presenting as azoospermia. J Urol, 1999. 161: 1571.

- Dieckmann, K.P., et al. Clinical epidemiology of testicular germ cell tumors. World J Urol, 2004. 22: 2.

- Eisenberg, M.L., et al. Increased risk of cancer among azoospermic men. Fertil Steril, 2013. 100: 681.

- Salonia, A., et al. Are infertile men less healthy than fertile men? Results of a prospective case-control survey. Eur Urol, 2009. 56: 1025.

- Ventimiglia, E., et al. Infertility as a proxy of general male health: results of a cross-sectional survey. Fertil Steril, 2015. 104: 48.

- Guo, D., et al. Hypertension and Male Fertility. World J Mens Health, 2017. 35: 59.

- Del Giudice, F., et al. Increased Mortality Among Men Diagnosed With Impaired Fertility: Analysis of US Claims Data. Urology, 2021. 147: 143.

- Glazer, C.H., et al. Male factor infertility and risk of death: a nationwide record-linkage study. Hum Reprod, 2019. 34: 2266.

- Choy, J.T., et al. Male infertility as a window to health. Fertil Steril, 2018. 110: 810.

- Clementini, E., et al. Prevalence of chromosomal abnormalities in 2078 infertile couples referred for assisted reproductive techniques. Hum Reprod, 2005. 20: 437.

- Vincent, M.C., et al. Cytogenetic investigations of infertile men with low sperm counts: a 25-year experience. J Androl, 2002. 23: 18.

- Kohn, T.P., et al. The Prevalence of Y-chromosome Microdeletions in Oligozoospermic Men: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of European and North American Studies. Eur Urol, 2019. 76: 626.

- Jensen, C.F.S., et al. A Refined View on the Association Between Y-chromosome Microdeletions and Sperm Concentration. Eur Urol, 2019.

- Chillon, M., et al. Mutations in the cystic fibrosis gene in patients with congenital absence of the vas deferens. N Engl J Med, 1995. 332: 1475.

- De Braekeleer, M., et al. Mutations in the cystic fibrosis gene in men with congenital bilateral absence of the vas deferens. Mol Hum Reprod, 1996. 2: 669.

- Capogrosso, P., et al. Erectile Recovery After Radical Pelvic Surgery: Methodological Challenges and Recommendations for Data Reporting. J Sex Med, 2019.

- Bobjer, J., et al. High prevalence of androgen deficiency and abnormal lipid profile in infertile men with nonobstructive azoospermia. Int J Androl, 2012. 35: 688.

- Patel, D.P., et al. Sperm concentration is poorly associated with hypoandrogenism in infertile men. Urology, 2015. 85: 1062.

- Ventimiglia, E., et al. Primary, secondary and compensated hypogonadism: a novel risk stratification for infertile men. Andrology, 2017. 5: 505.

- Lotti, F., et al. Ultrasound of the male genital tract in relation to male reproductive health. Hum Reprod Update, 2015. 21: 56.

- Nowroozi, M.R., et al. Assessment of testicular perfusion prior to sperm extraction predicts success rate and decreases the number of required biopsies in patients with non-obstructive azoospermia. Int Urol Nephrol, 2015. 47: 53.

- Nariyoshi, S., et al. Ultrasonographically determined size of seminiferous tubules predicts sperm retrieval by microdissection testicular sperm extraction in men with nonobstructive azoospermia. Fertil Steril, 2020. 113: 97.

- Donoso, P., et al. Which is the best sperm retrieval technique for non-obstructive azoospermia? A systematic review. Hum Reprod Update, 2007. 13: 539.

- Bernie, A.M., et al. Comparison of microdissection testicular sperm extraction, conventional testicular sperm extraction, and testicular sperm aspiration for nonobstructive azoospermia: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Fertil Steril, 2015. 104: 1099.

- Caroppo, E., et al. Testicular histology may predict the successful sperm retrieval in patients with nonobstructive azoospermia undergoing conventional TESE: a diagnostic accuracy study. J Assist Reprod Genet, 2017. 34: 149.

- Cetinkaya, M., et al. Evaluation of Microdissection Testicular Sperm Extraction Results in Patients with NonObstructive Azoospermia: Independent Predictive Factors and Best Cutoff Values for Sperm Retrieval. Urol J, 2015. 12: 2436.

- Cocci, A., et al. Effectiveness of highly purified urofollitropin treatment in patients with idiopathic azoospermia before testicular sperm extraction. Urol J, 2018. 85: 19.

- Cissen, M., et al. Prediction model for obtaining spermatozoa with testicular sperm extraction in men with nonobstructive azoospermia. Hum Reprod, 2016. 31: 1934.

- Guler, I., et al. Impact of testicular histopathology as a predictor of sperm retrieval and pregnancy outcome in patients with nonobstructive azoospermia: correlation with clinical and hormonal factors. Andrologia, 2016. 48: 765.

- Yildirim, M.E., et al. The association between serum follicle-stimulating hormone levels and the success of microdissection testicular sperm extraction in patients with azoospermia. Urol J, 2014. 11: 1825.

- Ramasamy, R., et al. A comparison of models for predicting sperm retrieval before microdissection testicular sperm extraction in men with nonobstructive azoospermia. J Urol, 2013. 189: 638.

- Yang, Q., et al. Follicle-stimulating hormone as a predictor for sperm retrieval rate in patients with nonobstructive azoospermia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Asian J Androl, 2015. 17: 281.

- Alfano, M., et al. Anti-Mullerian Hormone-to-Testosterone Ratio is Predictive of Positive Sperm Retrieval in Men with Idiopathic Non-Obstructive Azoospermia. Sci Rep, 2017. 7: 17638.

- Krausz, C., et al. Y chromosome and male infertility: update, 2006. Front Biosci, 2006. 11: 3049.

- Corona, G., et al. Sperm recovery and ICSI outcomes in Klinefelter syndrome: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Hum Reprod Update, 2017. 23: 265.

- Beliveau, M.E., et al. The value of testicular ‘mapping’ in men with non-obstructive azoospermia. Asian J Androl, 2011. 13: 225.

- Turek, P.J., et al. Diagnostic findings from testis fine needle aspiration mapping in obstructed and nonobstructed azoospermic men. J Urol, 2000. 163: 1709.

- Meng, M.V., et al. Relationship between classic histological pattern and sperm findings on fine needle aspiration map in infertile men. Hum Reprod, 2000. 15: 1973.

- Ezeh, U.I., et al. A prospective study of multiple needle biopsies versus a single open biopsy for testicular sperm extraction in men with non-obstructive azoospermia. Hum Reprod, 1998. 13: 3075.

- Rosenlund, B., et al. A comparison between open and percutaneous needle biopsies in men with azoospermia. Hum Reprod, 1998. 13: 1266.

- Hauser, R., et al. Comparison of efficacy of two techniques for testicular sperm retrieval in nonobstructive azoospermia: multifocal testicular sperm extraction versus multifocal testicular sperm aspiration. J Androl, 2006. 27: 28.

- Jensen, C.F., et al. Multiple needle-pass percutaneous testicular sperm aspiration as first-line treatment in azoospermic men. Andrology, 2016. 4: 257.

- Schlegel, P.N. Testicular sperm extraction: microdissection improves sperm yield with minimal tissue excision. Hum Reprod, 1999. 14: 131.

- Sacca, A., et al. Conventional testicular sperm extraction (TESE) and non-obstructive azoospermia: Is there still a chance in the era of microdissection TESE? Results from a single non-academic community hospital. Andrology, 2016. 4: 425.

- Corona, G., et al. Sperm recovery and ICSI outcomes in men with non-obstructive azoospermia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update, 2019. 25: 733.

- Deruyver, Y., et al. Outcome of microdissection TESE compared with conventional TESE in non-obstructive azoospermia: A systematic review. Andrology, 2014. 2: 20.

- Ramasamy, R., et al. Structural and functional changes to the testis after conventional versus microdissection testicular sperm extraction. Urology, 2005. 65: 1190.

- Cannarella, R., et al. Effects of the selective estrogen receptor modulators for the treatment of male infertility: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Opin Pharmacother, 2019. 20: 1517.

- Achermann, A.P.P., et al. Microdissection testicular sperm extraction (micro-TESE) in men with infertility due to nonobstructive azoospermia: summary of current literature. Int Urol Nephrol, 2021. 53: 2193.

- Caroppo, E., et al. Intrasurgical parameters associated with successful sperm retrieval in patients with nonobstructive azoospermia undergoing salvage microdissection testicular sperm extraction. Andrology, 2021.

- Özman, O., et al. Efficacy of the second micro-testicular sperm extraction after failed first micro-testicular sperm extraction in men with nonobstructive azoospermia. Fertil Steril, 2021. 115: 915.

- Yücel, C., et al. Predictive factors of successful salvage microdissection testicular sperm extraction (mTESE) after failed mTESE in patients with non-obstructive azoospermia: Long-term experience at a single institute. Arch Ital Urol Androl, 2018. 90: 136.

- Amer, M., et al. Prospective comparative study between microsurgical and conventional testicular sperm extraction in non-obstructive azoospermia: follow-up by serial ultrasound examinations. Hum Reprod, 2000. 15: 653.

- Eliveld, J., et al. The risk of TESE-induced hypogonadism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update, 2018. 24: 442.

- Billa, E., et al. Endocrine Follow-Up of Men with Non-Obstructive Azoospermia Following Testicular Sperm Extraction. J Clin Med, 2021. 10.

- Shinjo, E., et al. The effect of human chorionic gonadotropin-based hormonal therapy on intratesticular testosterone levels and spermatogonial DNA synthesis in men with non-obstructive azoospermia. Andrology, 2013. 1: 929.

- Oka, S., et al. Effects of human chorionic gonadotropin on testicular interstitial tissues in men with nonobstructive azoospermia. Andrology, 2017. 5: 232.

- Foresta, C., et al. Suppression of the high endogenous levels of plasma FSH in infertile men are associated with improved Sertoli cell function as reflected by elevated levels of plasma inhibin B. Hum Reprod, 2004. 19: 1431.

- Hussein, A., et al. Clomiphene administration for cases of nonobstructive azoospermia: a multicenter study. J Androl, 2005. 26: 787.

- Tharakan, T., et al. The Role of Hormone Stimulation in Men With Nonobstructive Azoospermia Undergoing Surgical Sperm Retrieval. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2020. 105.

- Gul, U., et al. The effect of human chorionic gonadotropin treatment before testicular sperm extraction in nonobstructive azoospermia. J Clin Analyt Med, 2016. 7: 55.

- Shiraishi, K., et al. Salvage hormonal therapy after failed microdissection testicular sperm extraction: A multiinstitutional prospective study. Int J Urol, 2016. 23: 496.

- Shiraishi, K., et al. Human chorionic gonadotrophin treatment prior to microdissection testicular sperm extraction in non-obstructive azoospermia. Hum Reprod, 2012. 27: 331.

- Reifsnyder, J.E., et al. Role of optimizing testosterone before microdissection testicular sperm extraction in men with nonobstructive azoospermia. J Urol, 2012. 188: 532.

- Farquhar, C., et al. Assisted reproductive technology: an overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2015: Cd010537.

- Farquhar, C., et al. Assisted reproductive technology: an overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2018. 8: Cd010537.

- Kandavel, V., et al. Does intra-uterine insemination have a place in modern ART practice? Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol, 2018. 53: 3.

- Veltman-Verhulst, S.M., et al. Intra-uterine insemination for unexplained subfertility. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2016. 2: Cd001838.

- Ombelet, W., et al. Semen quality and prediction of IUI success in male subfertility: a systematic review. Reprod Biomed Online, 2014. 28: 300.

- Adamson, G.D., et al. International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technology: world report on assisted reproductive technology, 2011. Fertil Steril, 2018. 110: 1067.

- Wilkes, S. NICE CG156: fertility update. What it means for general practitioners. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care, 2013. 39: 241.

- Bensdorp, A.J., et al. Prevention of multiple pregnancies in couples with unexplained or mild male subfertility: randomised controlled trial of in vitro fertilisation with single embryo transfer or in vitro fertilisation in modified natural cycle compared with intrauterine insemination with controlled ovarian hyperstimulation. BMJ, 2015. 350: g7771.

- Goverde, A.J., et al. Further considerations on natural or mild hyperstimulation cycles for intrauterine insemination treatment: effects on pregnancy and multiple pregnancy rates. Hum Reprod, 2005. 20: 3141.

- Shapiro, B.S., et al. Clinical rationale for cryopreservation of entire embryo cohorts in lieu of fresh transfer. Fertil Steril, 2014. 102: 3.

- Ozgur, K., et al. Higher clinical pregnancy rates from frozen-thawed blastocyst transfers compared to fresh blastocyst transfers: a retrospective matched-cohort study. J Assist Reprod Genet, 2015. 32: 1483.

- Sha, T., et al. Pregnancy-related complications and perinatal outcomes resulting from transfer of cryopreserved versus fresh embryos in vitro fertilization: a meta-analysis. Fertil Steril, 2018. 109: 330.

- NICE. Fertility Problems: Assessment and Treatment Guidelines.

- Devroey, P., et al. A review of ten years experience of ICSI. Hum Reprod Update, 2004. 10: 19.

- Rubino, P., et al. The ICSI procedure from past to future: a systematic review of the more controversial aspects. Hum Reprod Update, 2016. 22: 194.

- Palermo, G.D., et al. Intracytoplasmic sperm injection: state of the art in humans. Reproduction, 2017. 154: F93.

- Esteves, S.C., et al. Intracytoplasmic sperm injection for male infertility and consequences for offspring. Nat Rev Urol, 2018. 15: 535.

- Van Peperstraten, A., et al. Techniques for surgical retrieval of sperm prior to intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) for azoospermia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2008: Cd002807.

- Ohlander, S., et al. Impact of fresh versus cryopreserved testicular sperm upon intracytoplasmic sperm injection pregnancy outcomes in men with azoospermia due to spermatogenic dysfunction: a meta-analysis. Fertil Steril, 2014. 101: 344.

- Esteves, S.C., et al. Reproductive outcomes of testicular versus ejaculated sperm for intracytoplasmic sperm injection among men with high levels of DNA fragmentation in semen: systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril, 2017. 108: 456.

- Abhyankar, N., et al. Use of testicular versus ejaculated sperm for intracytoplasmic sperm injection among men with cryptozoospermia: a meta-analysis. Fertil Steril, 2016. 105: 1469.

- D’Angelo, A., et al. Coasting (withholding gonadotrophins) for preventing ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2017. 5: Cd002811.

- Multiple gestation associated with infertility therapy: an American Society for Reproductive Medicine Practice Committee opinion. Fertil Steril, 2012. 97: 825.

- Practice Bulletin No. 169: Multifetal Gestations: Twin, Triplet, and Higher-Order Multifetal Pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol., 2016. 128: e131.

- Behrman, E.R. et al. Preterm Birth: Causes, Consequences, and Prevention. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding Premature Birth and Assuring Healthy Outcomes. 2007.

- Jain, T., et al. 30 years of data: impact of the United States in vitro fertilization data registry on advancing fertility care. Fertil Steril, 2019. 111: 477.

- Boulet, S.L., et al. Assisted Reproductive Technology and Birth Defects Among Liveborn Infants in Florida, Massachusetts, and Michigan, 2000-2010. JAMA Pediatr, 2016. 170: e154934.

- Liberman, R.F., et al. Assisted Reproductive Technology and Birth Defects: Effects of Subfertility and Multiple Births. Birth Defects Res, 2017. 109: 1144.

- Spaan, M., et al. Risk of cancer in children and young adults conceived by assisted reproductive technology. Hum Reprod, 2019. 34: 740.

- Patel, A., et al. “In Cycles of Dreams, Despair, and Desperation:” Research Perspectives on Infertility Specific Distress in Patients Undergoing Fertility Treatments. J Hum Reprod Sci, 2018. 11: 320.

- Fisher, J.R., et al. Psychological and social aspects of infertility in men: an overview of the evidence and implications for psychologically informed clinical care and future research. Asian J Androl, 2012. 14: 121.

- Warchol-Biedermann, K. The Risk of Psychiatric Morbidity and Course of Distress in Males Undergoing Infertility Evaluation Is Affected by Their Factor of Infertility. Am J Mens Health, 2019. 13: 1557988318823904.

- Tharakan, T., et al. Male Sexual and Reproductive Health-Does the Urologist Have a Role in Addressing Gender Inequality in Life Expectancy? Eur Urol focus, 2019: S2405.

- McQuaid, J.W., et al. Ejaculatory duct obstruction: current diagnosis and treatment. Curr Urol Rep, 2013. 14: 291.

- WHO. The health and well-being of men in the WHO European Region: better health through a gender approach. 2018.

- Salonia, A., et al. SARS-CoV-2, testosterone and frailty in males (PROTEGGIMI): A multidimensional research project. Andrology, 2021. 9: 19.

- Hanson, B.M., et al. Male infertility: a biomarker of individual and familial cancer risk. Feril Steril, 2018. 109: 6.

- Brubaker, W.D., et al. Increased risk of autoimmune disorders in infertile men: analysis of US claims data. Andrology, 2018. 6: 94.

- Glazer, C.H., et al. Male factor infertility and risk of multiple sclerosis: A register-based cohort study. Mult Scler, 2017: 1352458517734069.

- Wang, N.N., et al. The association between varicocoeles and vascular disease: an analysis of U.S. claims data. Andrology, 2018. 6: 99.

- Vlachopoulos, C.V., et al. Prediction of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality with erectile dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes, 2013. 6: 99.

- Dong, J.Y., et al. Erectile dysfunction and risk of cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2011. 58: 1378.

- Zhao, B., et al. Erectile Dysfunction Predicts Cardiovascular Events as an Independent Risk Factor: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Sex Med, 2019. 16: 1005.

- Guo, W., et al. Erectile dysfunction and risk of clinical cardiovascular events: a meta-analysis of seven cohort studies. J Sex Med, 2010. 7: 2805.

- Yamada, T., et al. Erectile dysfunction and cardiovascular events in diabetic men: a meta-analysis of observational studies. PLoS One, 2012. 7: e43673.

- Osondu, C.U., et al. The relationship of erectile dysfunction and subclinical cardiovascular disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vasc Med, 2018. 23: 9.

- Fan, Y., et al. Erectile dysfunction and risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in the general population: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. World J Urol, 2018. 36: 1681.

- Wilkins, E., et al., European Heart Network – Cardiovascular Disease Statistics 2017, Brussels.

- van Bussel, E.F., et al. Predictive value of traditional risk factors for cardiovascular disease in older people: A systematic review. Prev Med, 2020. 132: 105986.

- Gerdts, E., et al. Sex differences in cardiometabolic disorders. Nat Med, 2019. 25: 1657.

- WHO. World Health Statistics 2019: Monitoring Health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals. 2019.

- Sandberg, K., et al. Sex differences in primary hypertension. Biol Sex Differ, 2012. 3: 7.

- Everett, B., et al. Gender differences in hypertension and hypertension awareness among young adults. Biodemography Soc Biol, 2015. 61: 1.

- WHO. Gender, Women And the Tobacco Epidemic. 2010.

- Navar-Boggan, A.M., et al. Hyperlipidemia in early adulthood increases long-term risk of coronary heart disease. Circulation, 2015. 131: 451.

- Stamler, J., et al. The Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial (MRFIT)–importance then and now. JAMA, 2008. 300: 1343.

- Seidell, J.C., et al. Fat distribution and gender differences in serum lipids in men and women from four European communities. Atherosclerosis, 1991. 87: 203.

- Hazzard, W.R. Atherogenesis: why women live longer than men. Geriatrics, 1985. 40: 42.

- Burnett, A.L., et al. Erectile Dysfunction: AUA Guideline. J Urol, 2018. 200: 633.

- Mulhall, J.P., et al. Evaluation and Management of Testosterone Deficiency: AUA Guideline. J Urol, 2018. 200: 423.

- Fode, M., et al. Late-onset Hypogonadism and Testosterone Therapy – A Summary of Guidelines from the American Urological Association and the European Association of Urology. Eur Urol Focus, 2019. 5: 539.

Author Correspondence:

Prof. Dr. Semir A. Salim. Al Samarrai

Medical Director of Professor Al Samarrai Medical Center.

Dubai Healthcare City, Al-Razi Building 64, Block D, 2nd Floor, Suite 2018

E-mail: semiralsamarrai@hotmail.com

Tel: +97144233669