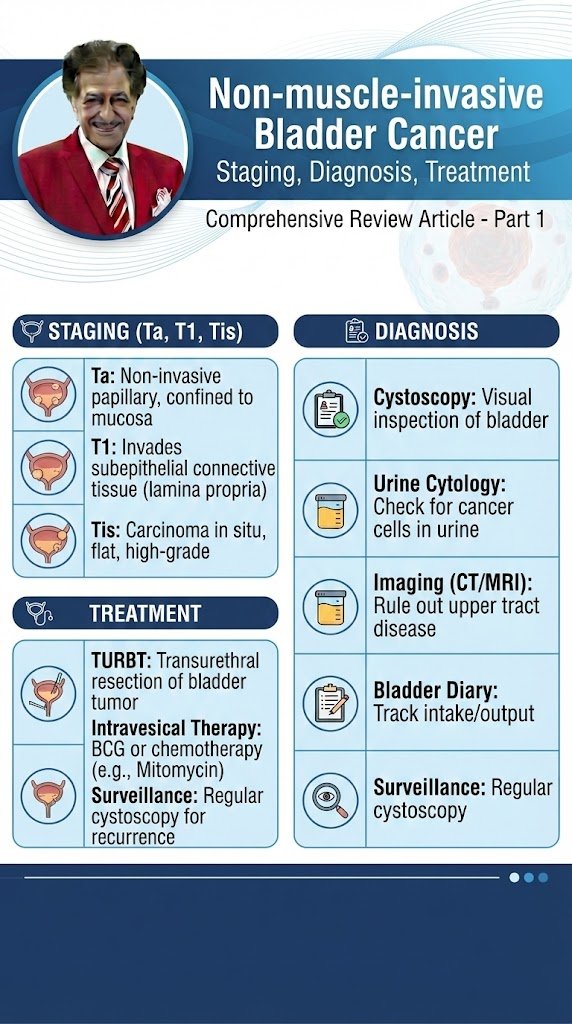

Non-muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer

Part 1

Comprehensive Review Article

Prof. Dr. Semir. A. Salim. Al Samarrai

EPIDEMIOLOGY, AETIOLOGY AND PATHOLOGY:

- Epidemiology

Bladder cancer (BC) is the seventh most commonly diagnosed cancer in the male population worldwide, while it drops to tenth when both genders are considered [1]. The worldwide age-standardised incidence rate (per 100,000 person/years) is 9.5 in men and 2.4 in women [1]. In the European Union the age-standardised incidence rate is 20 for men and 4.6 for women [1]. Worldwide, the BC age-standardised mortality rate (per 100,000 person/years) was 3.3 for men vs. 0.86 for women [1]. Bladder cancer incidence and mortality rates vary across countries due to differences in risk factors, detection and diagnostic practices, and availability of treatments. The variations are, however, partly caused by the different methodologies used and the quality of data collection [2]. The incidence and mortality of BC has decreased in some registries, possibly reflecting the decreased impact of causative agents [3]. Approximately 75% of patients with BC present with a disease confined to the mucosa (stage Ta, CIS) or submucosa (stage T1); in younger patients (< 40 years of age) this percentage is even higher [4]. Patients with TaT1 and CIS have a high prevalence due to long-term survival in many cases and lower risk of cancer-specific mortality compared to T2-4 tumours [1,2].

- Aetiology

Tobacco smoking is the most important risk factor for BC, accounting for approximately 50% of cases [2,3, 5–7]. The risk of BC increases with smoking duration and smoking intensity [6]. Low-tar cigarettes are not associated with a lower risk of developing BC [6]. The risk associated with electronic cigarettes is not adequately assessed; however, carcinogens have been identified in urine [8]. Environmental exposure to tobacco smoke is also associated with an increased risk of BC [2]. Tobacco smoke contains aromatic amines and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, which are renally excreted. Occupational exposure to aromatic amines, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and chlorinated hydrocarbons is the second most important risk factor for BC, accounting for about 10% of all cases. This type of occupational exposure occurs mainly in industrial plants which process paint, dye, metal, and petroleum products [2, 3, 9, 10]. In developed industrial settings these risks have been reduced by work-safety guidelines; therefore, chemical workers no longer have a higher incidence of BC compared to the general population [2, 9, 10]. Recently, greater occupational exposure to diesel exhaust has been suggested as a significant risk factor (odds ratio [OR]: 1.61; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.08–2.40) [11]. While family history seems to have little impact [12] and, to date, no overt significance of any genetic variation for BC has been shown; genetic predisposition has an influence on the incidence of BC via its impact on susceptibility to other risk factors [2, 13–17]. This has been suggested to lead to familial clustering of BC with an increased risk for first- and second-degree relatives (hazard ratio [HR]: 1.69; 95% CI: 1.47−1.95) [18]. Although the impact of drinking habits is uncertain, the chlorination of drinking water and subsequent levels of trihalomethanes are potentially carcinogenic, also exposure to arsenic in drinking water increases risk [2, 19].

Arsenic intake and smoking have a combined effect [20]. The association between personal hair dye use and risk remains uncertain; an increased risk has been suggested in users of permanent hair dyes with a slow NAT2 acetylation phenotype [2] but a large prospective cohort study could not identify an association between hair dye and risk of most cancer and cancer-related mortality [21]. Dietary habits seem to have limited impact, recently protective impact of flavonoids has been suggested and a Mediterranean diet, characterised by a high consumption of vegetables and non-saturated fat (olive oil) and moderate consumption of protein, was linked to some reduction of BC risk (HR: 0.85, 95% CI: 0.77−0.93) [22–27]. The impact of an increased consumption of fruits has been suggested to reduce the risk of BC; to date, this effect has been demonstrated to be significant in women only (HR: 0.92; 95% CI: 0.85–0.99) [28]. Exposure to ionizing radiation is connected with increased risk; a weak association was also suggested for cyclophosphamide and pioglitazone [2, 19, 29]. The impact of metabolic factors (body mass index, blood pressure, plasma glucose, cholesterol, and triglycerides) is uncertain [30]. Schistosomiasis, a chronic endemic cystitis based on recurrent infection with a parasitic trematode, is also a cause of BC [2].

PATHOLOGICAL STAGING AND CLASSIFICATION SYSTEMS:

- Definition of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer

LE 2a 3 3 Tumours confined to the mucosa and invading the lamina propria are classified as stage Ta and T1, respectively, according to the Tumour, Node, Metastasis (TNM) classification system [31]. Intra-epithelial, highgrade (HG) tumours confined to the mucosa are classified as CIS (Tis). All of these tumours can be treated by transurethral resection of the bladder (TURB), eventually in combination with intravesical instillations and are therefore grouped under the heading of NMIBC for therapeutic purposes. The term ‘non-muscle-invasive BC’ represents a group definition and all tumours should be characterised according to their stage, grade, and further pathological characteristics.

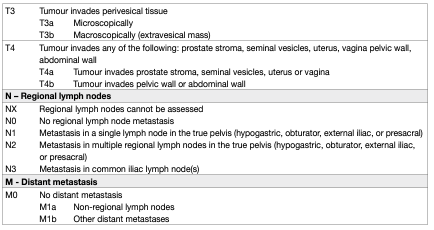

- Tumour, Node, Metastasis Classification (TNM)

The latest TNM classification approved by the Union International Contre le Cancer (UICC) (8th Edn.) is referred to (Table 1) [31].

Table 1: 2017 TNM classification of urinary bladder cancer

- T1 subclassification

The depth and extent of invasion into the lamina propria (T1 sub-staging) has been demonstrated to be of prognostic value in retrospective cohort studies [32, 33]. Its use is recommended by the most recent 2016 World Health Organization (WHO) classification [34]. T1 sub-staging methods are based either on micrometric (T1e and T1m) or histo-anatomic (T1a and T1b) principles; the optimal classification system, however, remains to be defined [34, 35].

- Carcinoma in situ and its classification

Carcinoma in situ is a flat, HG, non-invasive urothelial carcinoma. It can be missed or misinterpreted as an inflammatory lesion during cystoscopy if not biopsied. Carcinoma in situ is often multifocal and can occur in the bladder, but also in the upper urinary tract (UUT), prostatic ducts, and prostatic urethra [36]. From a clinical point of view, CIS may be classified as [37]: • Primary: isolated CIS with no previous or concurrent papillary tumours and no previous CIS;

• Secondary: CIS detected during follow-up of patients with a previous tumour that was not CIS;

• Concurrent: CIS in the presence of any other urothelial tumour in the bladder.

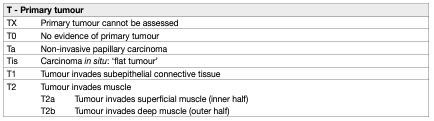

- Histological grading of non-muscle-invasive bladder urothelial carcinomas Types of histological grading systems

In 2004 the WHO published a histological classification system for urothelial carcinomas including papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential (PUNLMP), non-invasive papillary carcinoma low grade (LG) and HG. This system was also taken into the updated 2016 WHO classification and will be maintained in the upcoming WHO 2022. It provides a different patient stratification between individual categories compared to the older 1973 WHO classification, which distinguished between grade 1 (G1), grade 2 (G2) and grade 3 (G3) categories [34, 38]. There is a significant shift of patients between the categories of the WHO 1973 and the WHO 2004/2016 systems (see Figure 1), for example an increase in the number of HG patients (WHO 2004/2016) due to inclusion of a subset of G2 patients with a favourable prognosis compared to the G3 category (WHO 1973) [39]. According to a multi-institutional individual patient data (IPD) analysis, the proportion of tumours classified as PUNLMP (WHO 2004/2016) has decreased to very low levels in the last decade [40].

- Prognostic value of histological grading

A systematic review and meta-analysis did not show that the 2004/2016 classification outperforms the 1973 classification in prediction of recurrence and progression [39]. To compare the prognostic value of both WHO classifications, an IPD analysis of 5,145 primary TaT1 NMIBC patients from 17 centres throughout Europe and Canada was conducted. Patients had a transurethral resection of bladder Ftumour (TURBT) followed by intravesical instillations at the physician’s discretion. In this large prognostic factor study, the WHO 1973 and the WHO 2004/2016 were both prognostic for progression but not for recurrence. When compared, the WHO 1973 was a stronger prognosticator of progression in TaT1 NMIBC than the WHO 2004/2016. However, a 4-tier combination LG/G1, LG/G2, HG/G2 and HG/G3) of both classification systems proved to be superior to either classification system alone, as it divides the large group of G2 patients into two subgroups (LG/HG) with different prognoses [41].

In a subgroup of 3,311 patients with primary Ta bladder tumours, a similar prognosis was found for PUNLMP and Ta LG carcinomas [42]. Hence, these results do not support the continued use of PUNLMP as a separate grade category in the WHO 2004/2016.

- Clinical application of histological grading systems

• The WHO 2016 classification system is currently supported by the WHO for clinical application, nevertheless, the WHO 1973 is still being used by some pathologists.

• The most important parameters, which must be considered for clinical application of any grading system are its inter-observer reproducibility and prognostic value.

• To facilitate the clinical utilisation in daily practice, these guidelines provide recommendations for tumours classified by both classification systems.

Figure 1: Stratification of tumours according to grade in the WHO 1973 and 2004/2016 classifications

- Inter- and intra-observer variability in staging and grading

There is significant variability among pathologists for the diagnosis of CIS, for which agreement is achieved in only 70–78% of cases [43]. There is also inter-observer variability in the classification of stage T1 vs. Ta tumours and tumour grading in both the 1973 and 2004/2016 classifications. The general conformity between pathologists in staging and grading is 50–60% [44–47]. The WHO 2004/2016 classification provides slightly better reproducibility than the 1973 classification [39].

- Subtypes of urothelial carcinoma and lymphovascular invasion

Currently the following differentiations of urothelial carcinoma are used [48, 49]:

- urothelial carcinoma (more than 90% of all cases);

- urothelial carcinomas with partial squamous and/or glandular or trophoblastic differentiation;

- micropapillary urothelial carcinoma;

- nested variant (including large nested variant) and microcystic urothelial carcinoma;

- plasmacytoid, giant cell, signet ring, diffuse, undifferentiated;

- lymphoepithelioma-like;

- small-cell carcinomas;

- sarcomatoid urothelial carcinoma;

- neuroendocrine variant of urothelial carcinoma;

- some urothelial carcinomas with other rare differentiations.

Most variants of urothelial carcinoma have a worse prognosis than pure HG urothelial carcinoma [50, 51–58]. The presence of lymphovascular invasion (LVI) in TURB specimens is associated with an increased risk of pathological upstaging and worse prognosis [59–63].

- Tumour markers and molecular classification

Tumour markers and their prognostic role have been investigated [64-68]. These methods, in particular complex approaches such as the stratification of patients based on molecular classification, are promising but are not yet suitable for routine application [35, 69, 70].

DIAGNOSIS:

- Patient history

A focused patient history is mandatory.

- Signs and symptoms

Haematuria is the most common finding in NMIBC. Visible haematuria was found to be associated with higherstage disease compared to nonvisible haematuria [71]. Carcinoma in situ might be suspected in patients with lower urinary tract symptoms, especially irritative voiding symptoms.

- Physical examination

A focused urological examination is mandatory although it does not reveal NMIBC.

- Imaging

- Computed tomography urography and intravenous urography

Computed tomography (CT) urography is used to detect papillary tumours in the urinary tract, indicated by filling defects and/or hydronephrosis [72]. Intravenous urography (IVU) is an alternative if CT is not available [73], but particularly in muscleinvasive tumours of the bladder and in UTUCs, CT urography provides more information (including status of lymph nodes and neighbouring organs). The necessity to perform a baseline CT urography once a bladder tumour has been detected is questionable due to the low incidence of significant findings which can be obtained [74–76]. The incidence of UTUCs is low (1.8%), but increases to 7.5% in tumours located in the trigone [75]. The risk of UTUC during follow-up increases in patients with multiple and high-risk tumours [77].

- Ultrasound

Ultrasound (US) may be performed as an adjunct to physical examination as it has moderate sensitivity to a wide range of abnormalities in the upper- and lower urinary tract. It permits characterisation of renal masses, detection of hydronephrosis, and visualisation of intraluminal masses in the bladder, but cannot rule out all potential causes of haematuria [78, 79]. It cannot reliably exclude the presence of UTUC and cannot replace CT urography.

- Multi-parametric magnetic resonance imaging

The role of multi-parametric magnetic resonance imaging (mpMRI) has not yet been established in BC diagnosis and staging. A standardised methodology of MRI reporting (Vesical Imaging-Reporting and Data System [VI-RADS]) in patients with BC has recently been published and requires further validation [80]. A first systematic review of 8 studies showed that the VI-RADS scoring system can accurately differentiate NMIBC from MIBC with high inter-observer agreement rates [81]. A diagnosis of CIS cannot be made with imaging methods alone (CT urography, IVU, US or MRI).

- Urinary cytology

The examination of voided urine or bladder-washing specimens for exfoliated cancer cells has high sensitivity in HG and G3 tumours (84%), but low sensitivity in LG/G1 tumours (16%) [82]. The sensitivity in CIS detection is 28–100% [83]. Cytology is useful, particularly as an adjunct to cystoscopy, in patients with HG/G3 tumours. Positive voided urinary cytology can indicate a urothelial carcinoma anywhere in the urinary tract; negative cytology, however, does not exclude its presence. Cytological interpretation is user-dependent [84, 85]. Evaluation can be hampered by low cellular yield, urinary tract infections, stones, or intravesical instillations, however, in experienced hands specificity exceeds 90% [84].

A standardised reporting system known as The Paris System published in 2016 redefined urinary cytology diagnostic categories as follows [86]:

• No adequate diagnosis possible (No diagnosis);

• Negative for urothelial carcinoma (Negative);

• Atypical urothelial cells (Atypia);

• Suspicious for HG urothelial carcinoma (Suspicious);

• High-grade/G3 urothelial carcinoma (Malignant).

The principle of the system and its terminology underlines the role of urinary cytology in detection of G3 and HG tumours. The Paris system for reporting urinary cytology has been validated in several retrospective studies [87, 88].

One cytospin slide from the sample is usually sufficient [89]. In patients with suspicious cytology repeat investigation is advised [90].

- Urinary molecular marker tests

Driven by the low sensitivity of urine cytology, numerous urinary tests have been developed [91]. None of these markers have been accepted as routine practice by any clinical guidelines for diagnosis or follow-up.

The following conclusions can be drawn regarding the existing tests:

• Sensitivity is usually higher at the cost of lower specificity compared to urine cytology [92–97].

• Benign conditions and previous BCG instillations may influence the results of many urinary marker tests [92–94].

• Requirements for sensitivity and specificity of a urinary marker test largely depend on the clinical context of the patient (screening, primary detection, follow-up [high-risk, low/intermediate-risk]) [93, 94].

• The wide range in performance of the markers and low reproducibility may be explained by patient selection and complicated laboratory methods required [94, 95, 98-105].

• Positive results of cytology, UroVysion (FISH), Nuclear Matrix Protein (NMP)22®, Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor (FGFR)3/Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase (TERT) and microsatellite analysis in patients with negative cystoscopy and upper tract work-up, may identify patients more likely to experience disease recurrence and possibly progression [99, 101, 104–109].

• Promising novel urinary biomarkers, assessing multiple targets, have been tested in prospective multicentre studies [98, 100, 104, 110-113].

- Potential application of urinary cytology and markers

The following objectives of urinary cytology or molecular tests must be considered.

Screening of the population at risk of bladder cancer:

The application of haematuria dipstick, followed by FGFR3, NMP22® or UroVysion tests if dipstick is positive has been reported in BC screening in high-risk populations [114, 115]. The low incidence of BC in the general population and the short lead-time impairs feasibility and cost-effectiveness [107, 115]. Routine screening for BC is not recommended [107, 114, 115].

- Exploration of patients after haematuria or other symptoms suggestive of bladder cancer (primary detection)

It is generally accepted that none of the currently available tests can replace cystoscopy. However, urinary cytology or biomarkers can be used as an adjunct to cystoscopy to detect missed tumours, particularly CIS. In this setting, specificity is particularly important.

- Surveillance of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer

Research has been carried out into the usefulness of urinary cytology vs. markers in the follow-up of NMIBC [198, 99, 111, 112, 116].

- Follow-up of high-risk non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer

High-risk tumours should be detected early in follow-up and the percentage of tumours missed should be as low as possible. Therefore, the best surveillance strategy for these patients will continue to include cystoscopy and cytology.

- Follow-up of low/intermediate-risk non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer

To reduce the number of cystoscopy procedures, urinary markers should be able to detect recurrence before the tumours are large, numerous and muscle invasive. The limitation of urinary cytology and current urinary markers is their low sensitivity for LG recurrences [93, 99]. According to current knowledge, no urinary marker can replace cystoscopy during follow-up or lower cystoscopy frequency in a routine fashion. One prospective randomised study (RCT) found that knowledge of positive test results (microsatellite analysis) can improve the quality of follow-up cystoscopy [117], supporting the adjunctive role of a non-invasive urine test performed prior to follow-up cystoscopy [117]. Four of the promising and commercially available urine biomarkers, Cx-Bladder [98, 113], ADX-Bladder [110], Xpert Bladder [111] and EpiCheck [112], although not tested in RCTs, have such high sensitivities and negative predictive values in the referenced studies for HG disease that these biomarkers may approach the sensitivity of cystoscopy. These 4 tests might be used to replace and/or postpone cystoscopy as they may identify the rare HG recurrences occurring in low/intermediate NMIBC.

Cystoscopy:

The diagnosis of papillary BC ultimately depends on cystoscopic examination of the bladder and histological evaluation of sampled tissue by either cold-cup biopsy or resection. Carcinoma in situ is diagnosed by a combination of cystoscopy, urine cytology, and histological evaluation of multiple bladder biopsies [118]. Cystoscopy is initially performed as an outpatient procedure. A flexible instrument with topical intraurethral anaesthetic lubricant instillation results in better compliance compared to a rigid instrument, especially in men [119, 120]. To temporary increase the urethral pressure by irrigation ‘bag squeeze’ when passing membranous and prostatic urethra with a flexible cystoscope in males also decreases pain during the procedure [121, 122].

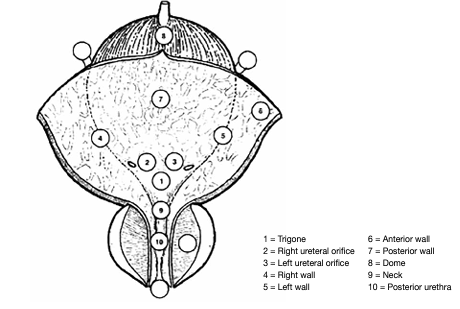

Figure 2: Bladder diagram

Transurethral resection of TaT1 bladder tumours:

- Strategy of the procedure

The goal of TURB in TaT1 BC is to make the correct diagnosis and completely remove all visible lesions. It is a crucial procedure in the management of BC. Transurethral resection of the bladder should be performed systematically in individual steps [123, 124]. The operative steps necessary to achieve a successful TURB include identifying the factors required to assign disease risk (number of tumours, size, multifocality, characteristics, concern for the presence of CIS, recurrent vs. primary tumour), clinical stage (bimanual examination under anaesthesia, assignment of clinical tumour stage), adequacy of the resection (visually complete resection, visualisation of muscle at the resection base), and presence of complications (assessment for perforation) [124, 125]. To measure the size of the largest tumour, one can use the end of cutting loop, which is approximately 1 cm wide, as a reference. The characteristics of the tumour are described as sessile, nodular, papillary, or flat.

Surgical and technical aspects of tumour resection:

- Surgical strategy of resection (piecemeal/separate resection, en-bloc resection)

A complete resection, performed by either fractioned or en-bloc technique, is essential to achieve a good prognosis [123, 126].

• Piecemeal resection in fractions (separate resection of the exophytic part of the tumour, the underlying bladder wall and the edges of the resection area) provides good information about the vertical and horizontal extent of the tumour [127].

• En-bloc resection using monopolar or bipolar current, Thulium-YAG or Holmium-YAG laser is feasible in selected exophytic tumours. It provides high-quality resected specimens with the presence of detrusor muscle in 96–100% of cases [123, 128-131]. The technique selected is dependent on the size and location of the tumour and experience of the surgeon.

- Evaluation of resection quality

The absence of detrusor muscle in the specimen is associated with a significantly higher risk of residual disease, early recurrence, and tumour under-staging [132]. The presence of detrusor muscle in the specimen is considered as a surrogate criterion of the resection quality and is required (except in Ta LG/G1 tumours). Surgical checklists and a quality performance indicator programme have shown to increase surgical quality (detrusor muscle presence) and decrease recurrence rates [124, 125, 133, 134]. It has been shown that surgical experience can improve TURB results, which supports the role of teaching programmes [135]. Virtual training on simulators is an emerging approach [136]. Its role in the teaching process still needs to be established [124]. Surgical experience and/or volume has been associated both with risk of complications [137], recurrence [138] and survival [139] in retrospective studies.

- Monopolar and bipolar resection

Compared to monopolar resection, bipolar resection has been introduced to reduce the risk of complications (e.g., bladder perforation due to obturator nerve stimulation) and to produce better specimens. Currently, the results remain controversial [140-143] as a systematic review of 13 RCTs (2,379 patients) showed no benefit of bipolar vs. monopolar TURB for efficacy and safety [143].

- Office-based fulguration and laser vaporisation

In patients with a history of small, Ta LG/G1 tumours, fulguration, or laser vaporisation of small papillary recurrences on an outpatient basis can reduce the therapeutic burden [144, 145]. There are no prospective comparative studies assessing the oncological outcomes.

- Resection of small papillary bladder tumours at the time of transurethral resection of the prostate

It is not uncommon to detect bladder tumours in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Provided these tumours are papillary by aspect, rather small and not extensively multifocal, it seems feasible to resect these tumours and continue with the resection of the prostate [146, 147]. Although high-quality evidence is limited, simultaneous TURB and TUR of the prostate does not appear to lead to any increased risk of tumour recurrence or progression [148].

Bladder biopsies:

Carcinoma in situ can present as a velvet-like, reddish area, indistinguishable from inflammation, or it may not be visible at all. For this reason, biopsies from suspicious urothelium should be taken. In patients with positive urine cytology, and normal-looking mucosa at cystoscopy, mapping biopsies are recommended [149, 150]. To obtain representative mapping of the bladder mucosa, biopsies should be taken from the trigone, bladder dome, right, left, anterior and posterior bladder wall [149, 150]. If the equipment is available, photodynamic diagnosis (PDD) is a useful tool to target the biopsy.

Prostatic urethral biopsies:

Involvement of the prostatic urethra and ducts in men with NMIBC has been reported. Palou et al. showed that in 128 men with T1G3 BC, the incidence of CIS in the prostatic urethra was 11.7% [151]. The risk of prostatic urethra or duct involvement is higher if the tumour is located at the trigone or bladder neck, in the presence of bladder CIS and multiple tumours [152]. Based on this observation, a biopsy from the prostatic urethra is necessary in some cases [151, 153, 154].

New methods of tumour visualization:

As a standard procedure, cystoscopy and TURB are performed using white light. However, the use of white light can lead to missing lesions that are present but not visible, which is why new technologies are being developed.

- Photodynamic diagnosis (fluorescence cystoscopy)

Photodynamic diagnosis is performed using violet light after intravesical instillation of 5-aminolaevulinic acid (ALA) or hexaminolaevulinic acid (HAL). It has been confirmed that fluorescence-guided biopsy and resection are more sensitive than conventional procedures for the detection of malignant tumours, particularly CIS [155, 156]. In a systematic review and meta-analysis, PDD had higher sensitivity than white light endoscopy in the pooled estimates for analyses at both the patient-level (92% vs. 71%) and biopsy-level (93% vs. 65%) [156]. A prospective RCT did not confirm a higher detection rate in patients with known positive cytology before TURB [157]. Photodynamic diagnosis had lower specificity than white-light endoscopy (63% vs. 81%) [156]. False-positivity can be induced by inflammation or recent TURB and during the first 3 months after BCG instillation [158, 159]. The beneficial effect of ALA or HAL fluorescence cystoscopy on recurrence rate in patients with TURB was evaluated. A systematic review and analysis of 14 RCTs including 2,906 patients, 6 using 5-ALA and 9 HAL, demonstrated a decreased risk of BC recurrence in the short and long term. There were, however, no differences in progression and mortality rates. The analysis demonstrated inconsistency between trials and potential susceptibility to performance and publication bias [160]. One RCT has shown a reduction in recurrence and progression with fluorescence-guided TURB as compared to white light TURB [161]. In another RCT flexible HAL-cystoscopy proved beneficial in the outpatient setting showing subsequent lower recurrence rates [162]. These results need to be validated by further studies.

- Narrow-band imaging

In narrow-band imaging (NBI), the contrast between normal urothelium and hyper-vascular cancer tissue is enhanced. Improved cancer detection has been demonstrated by NBI flexible cystoscopy and NBI-guided biopsies and resection [163-166]. A RCT assessed the reduction of recurrence rates if NBI is used during TURB. Although the overall results of the study were negative, a benefit after 3 and 12 months was observed for low-risk tumours (pTa LG, < 30 mm, no CIS) [167]. 5.11.3 Additional technologies Confocal laser micro-endoscopy is a high-resolution imaging probe designed to provide endoscopic histological grading in real time but requires further validation [168]. The Storz professional image enhancement system (IMAGE1 S, formally called SPIES) is an image enhancement system using 4 different light spectra but prospective data using this system are still limited [169].

Second resection:

- Detection of residual disease and tumour upstaging

The significant risk of residual tumour after initial TURB of TaT1 lesions has been demonstrated [126]. A systematic review analysing data of 8,409 patients with Ta or T1 HG BC demonstrated a 51% risk of persistence and an 8% risk of under-staging in T1 tumours. The analysis also showed a high risk of residual disease in Ta tumours, but this observation was based only on a limited number of cases. Most of the residual lesions were detected at the original tumour location [170]. Another meta-analysis of 3,556 patients with T1 tumours showed that the prevalence rate of residual tumours and upstaging to invasive disease after TURB remained high in a subgroup with detrusor muscle in the resection specimen. In the subgroup of 1,565 T1 tumours with detrusor muscle present, persistent tumour was found in 58% and under-staging occurred in 11% of cases [171]. Prospective trials suggest that post-operative positive urine cytology [172] and Xpert-test (urine mRNA test) [173] independently are associated with residual disease at second resection and risk of future recurrences, respectively. These data, however, need to be confirmed in further studies.

- The impact of second resection on treatment outcomes

A second TURB can increase recurrence-free survival (RFS) [174, 175], improve outcomes after BCG treatment [176] and provide prognostic information [177-180]. In a retrospective evaluation of a large multi-institutional cohort of 2,451 patients with BCG-treated T1 G3/HG tumours (a second resection was performed in 935 patients), the second resection improved RFS, progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) only in patients without detrusor muscle in the specimen of the initial resection [181].

- Timing of second resection

Retrospective evaluation showed that a second resection performed 14–42 days after initial resection provides longer RFS and PFS compared to second resection performed after 43–90 days [182]. Based on these arguments, a second TURB is recommended in selected cases 2 to 6 weeks after initial resection (for recommendations on patient selection.

- Recording of results

The results of the second resection (residual tumours and under-staging) reflect the quality of the initial TURB. As the goal is to improve the quality of the initial TURB, the results of the second resection should be recorded.

- Pathology report

Pathological investigation of the specimen(s) obtained by TURB and biopsies is an essential step in the decision-making process for BC [183]. Close co-operation between urologists and pathologists is required. A high quality of resected and submitted tissue and clinical information is essential for correct pathological assessment. To obtain all relevant information, the specimen collection, handling and evaluation, should respect the recommendations provided below [184, 185]. In difficult cases, an additional review by an experienced genitourinary pathologist can be considered.

REFERNCES:

- IARC, Cancer Today. Estimated number of new cases in 2020, worldwide, both sexes, all ages. 2021. 2022. https://gco.iarc.fr/today/online-analysis-table

- Burger, M., et al. Epidemiology and risk factors of urothelial bladder cancer. Eur Urol, 2013. 63: 234. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22877502/

- Teoh, J.Y., et al. Global Trends of Bladder Cancer Incidence and Mortality, and Their Associations with Tobacco Use and Gross Domestic Product Per Capita. Eur Urol, 2020. 78: 893. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32972792/

- Comperat, E., et al. Clinicopathological characteristics of urothelial bladder cancer in patients less than 40 years old. Virchows Arch, 2015. 466: 589. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25697540/

- Freedman, N.D., et al. Association between smoking and risk of bladder cancer among men and women. JAMA, 2011. 306: 737. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21846855/

- van Osch, F.H., et al. Quantified relations between exposure to tobacco smoking and bladder cancer risk: a meta-analysis of 89 observational studies. Int J Epidemiol, 2016. 45: 857. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27097748/

- Laaksonen, M.A., et al. The future burden of kidney and bladder cancers preventable by behavior modification in Australia: A pooled cohort study. Int J Cancer, 2020. 146: 874. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31107541/

- Bjurlin, M.A., et al. Carcinogen Biomarkers in the Urine of Electronic Cigarette Users and Implications for the Development of Bladder Cancer: A Systematic Review. Eur Urol Oncol, 2021. 4: 766. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32192941/

- Colt, J.S., et al. A case-control study of occupational exposure to metalworking fluids and bladder cancer risk among men. Occup Environ Med, 2014. 71: 667. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25201311/

- Pesch, B., et al. Screening for bladder cancer with urinary tumor markers in chemical workers with exposure to aromatic amines. Int Arch Occup Environ Health, 2013. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24129706/

- Koutros, S., et al. Diesel exhaust and bladder cancer risk by pathologic stage and grade subtypes. Environ Int, 2020. 135: 105346. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31864026/

- Egbers, L., et al. The prognostic value of family history among patients with urinary bladder cancer. Int J Cancer, 2015. 136: 1117. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24978702/

- Corral, R., et al. Comprehensive analyses of DNA repair pathways, smoking and bladder cancer risk in Los Angeles and Shanghai. Int J Cancer, 2014. 135: 335. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24382701/

- Figueroa, J.D., et al. Identification of a novel susceptibility locus at 13q34 and refinement of the 20p12.2 region as a multi-signal locus associated with bladder cancer risk in individuals of European ancestry. Hum Mol Genet, 2016. 25: 1203. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26732427/

- Zhong, J.H., et al. Association between APE1 Asp148Glu polymorphism and the risk of urinary cancers: a meta-analysis of 18 case-control studies. Onco Targets Ther, 2016. 9: 1499. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27042118/

- Al-Zalabani, A.H., et al. Modifiable risk factors for the prevention of bladder cancer: a systematic review of meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol, 2016. 31: 811. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27000312/

- Wu, J., et al. A Functional rs353293 Polymorphism in the Promoter of miR-143/145 Is Associated with a Reduced Risk of Bladder Cancer. PLoS One, 2016. 11: e0159115. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27438131/

- Martin, C., et al. Familial Cancer Clustering in Urothelial Cancer: A Population-Based Case-Control Study. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2018. 110: 527. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29228305/

- Steinmaus, C., et al. Increased lung and bladder cancer incidence in adults after in utero and earlylife arsenic exposure. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 2014. 23: 1529. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24859871/

- Koutros, S., et al. Potential effect modifiers of the arsenic-bladder cancer risk relationship. Int J Cancer, 2018. 143: 2640. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29981168/

- Zhang, Y., et al. Personal use of permanent hair dyes and cancer risk and mortality in US women: prospective cohort study. BMJ, 2020. 370: m2942. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32878860/

- Buckland, G., et al. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet and risk of bladder cancer in the EPIC cohort study. Int J Cancer, 2014. 134: 2504. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24226765/

- Liu, H., et al. Fruit and vegetable consumption and risk of bladder cancer: an updated meta-analysis of observational studies. Eur J Cancer Prev, 2015. 24: 508. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25642791/

- Vieira, A.R., et al. Fruits, vegetables, and bladder cancer risk: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Cancer Med, 2015. 4: 136. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25461441/

- Zhao, L., et al. Association of body mass index with bladder cancer risk: a dose-response metaanalysis of prospective cohort studies. Oncotarget, 2017. 8: 33990. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28389625/

- Rossi, M., et al. Flavonoids and bladder cancer risk. Cancer Causes Control, 2019. 30: 527. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30903485/

- Witlox, W.J.A., et al. An inverse association between the Mediterranean diet and bladder cancer risk: a pooled analysis of 13 cohort studies. Eur J Nutr, 2020. 59: 287. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30737562/

- Jochems, S.H.J., et al. Fruit consumption and the risk of bladder cancer: A pooled analysis by the Bladder Cancer Epidemiology and Nutritional Determinants Study. Int J Cancer, 2020. 147: 2091. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32285440/

- Tuccori, M., et al. Pioglitazone use and risk of bladder cancer: population based cohort study. BMJ, 2016. 352: i1541. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27029385/

- Teleka, S., et al. Risk of bladder cancer by disease severity in relation to metabolic factors and smoking: A prospective pooled cohort study of 800,000 men and women. Int J Cancer, 2018. 143: 3071. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29756343/

- TNM classification of malignant tumors. UICC International Union Against Cancer. 8th edn., G.M. Brierley JD, Wittekind C., Editor. 2017, Wiley-Blackwell and UICC: New York, USA. https://www.uicc.org/news/8th-edition-uicc-tnm-classification-malignant-tumors-published

- Otto, W., et al. WHO 1973 grade 3 and infiltrative growth pattern proved, aberrant E-cadherin expression tends to be of predictive value for progression in a series of stage T1 high-grade bladder cancer after organ-sparing approach. Int Urol Nephrol, 2017. 49: 431. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28035618/

- van Rhijn, B.W., et al. A new and highly prognostic system to discern T1 bladder cancer substage. Eur Urol, 2012. 61: 378. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22036775/

- Moch, H., et al. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs. 4th ed. 2016, Lyon, France https://publications.iarc.fr/Book-And-Report-Series/Who-Classification-Of-Tumours/WHOClassification-Of-Tumours-Of-The-Urinary-System-And-Male-Genital-Organs-2016

- Compérat, E., et al. The Genitourinary Pathology Society Update on Classification of Variant Histologies, T1 Substaging, Molecular Taxonomy, and Immunotherapy and PD-L1 Testing Implications of Urothelial Cancers. Adv Anat Pathol, 2021. 28: 196. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34128484/

- Andersson, M., et al. The diagnostic challenge of suspicious or positive malignant urine cytology findings when cystoscopy findings are normal: an outpatient blue-light flexible cystoscopy may solve the problem. Scand J Urol, 2021. 55: 263. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34037496/

- Lamm, D., et al. Updated concepts and treatment of carcinoma in situ. Urol Oncol, 1998. 4: 130. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21227218/

- Sauter G, et al. Tumours of the urinary system: non-invasive urothelial neoplasias. In: WHO classification of classification of tumours of the urinary system and male genital organs., A.F. Sauter G, Amin M, et al. Eds. 2004, IARCC Press: Lyon. https://publications.iarc.fr/Book-And-Report-Series/Who-Classification-Of-Tumours/WHOClassification-Of-Tumours-Of-The-Urinary-System-And-Male-Genital-Organs-2016

- Soukup, V., et al. Prognostic Performance and Reproducibility of the 1973 and 2004/2016 World Health Organization Grading Classification Systems in Non-muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer: A European Association of Urology Non-muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer Guidelines Panel Systematic Review. Eur Urol, 2017. 72: 801. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28457661/

- Hentschel, A.E., et al. Papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential (PUN-LMP): Still a meaningful histo-pathological grade category for Ta, noninvasive bladder tumors in 2019? Urol Oncol, 2020. 38: 440. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31704141/

- van Rhijn, B.W.G., et al. Prognostic Value of the WHO1973 and WHO2004/2016 Classification Systems for Grade in Primary Ta/T1 Non-muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer: A Multicenter European Association of Urology Non-muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer Guidelines Panel Study. Eur Urol Oncol, 2021. 4: 182. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33423944/

- Sylvester, R.J., et al. European Association of Urology (EAU) Prognostic Factor Risk Groups for Non-muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer (NMIBC) Incorporating the WHO 2004/2016 and WHO 1973 Classification Systems for Grade: An Update from the EAU NMIBC Guidelines Panel. Eur Urol, 2021: 480. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33419683/

- Witjes, J.A., et al. Review pathology in a diagnostic bladder cancer trial: effect of patient risk category. Urology, 2006. 67: 751. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16566990/

- May, M., et al. Prognostic accuracy of individual uropathologists in noninvasive urinary bladder carcinoma: a multicentre study comparing the 1973 and 2004 World Health Organisation classifications. Eur Urol, 2010. 57: 850. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19346063/

- van Rhijn, B.W., et al. Pathological stage review is indicated in primary pT1 bladder cancer. BJU Int, 2010. 106: 206. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20002439/

- Comperat, E., et al. An interobserver reproducibility study on invasiveness of bladder cancer using virtual microscopy and heatmaps. Histopathology, 2013. 63: 756. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24102813/

- Mangrud, O.M., et al. Reproducibility and prognostic value of WHO1973 and WHO2004 grading systems in TaT1 urothelial carcinoma of the urinary bladder. PLoS One, 2014. 9: e83192. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24409280/

- Veskimae, E., et al. What Is the Prognostic and Clinical Importance of Urothelial and Nonurothelial Histological Variants of Bladder Cancer in Predicting Oncological Outcomes in Patients with Muscle-invasive and Metastatic Bladder Cancer? A European Association of Urology Muscle Invasive and Metastatic Bladder Cancer Guidelines Panel Systematic Review. Eur Urol Oncol, 2019. 2: 625. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31601522/

- Comperat, E.M., et al. Grading of Urothelial Carcinoma and The New “World Health Organisation Classification of Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs 2016”. Eur Urol Focus, 2019. 5: 457. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29366854/

- Witjes, J., et al. EAU Guidelines on Muscle-invasive and Metastatic Bladder Cancer 2022. Edn. presented at the 37th EAU Annual Congress Amsterdam. European Association of Urology Guidelines Office Arnhem, The Netherlands. https://uroweb.org/guideline/bladder-cancer-muscle-invasive-and-metastatic/

- Comperat, E., et al. Micropapillary urothelial carcinoma of the urinary bladder: a clinicopathological analysis of 72 cases. Pathology, 2010. 42: 650. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21080874/

- Kaimakliotis, H.Z., et al. Plasmacytoid variant urothelial bladder cancer: is it time to update the treatment paradigm? Urol Oncol, 2014. 32: 833. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24954925/

- Willis, D.L., et al. Micropapillary bladder cancer: current treatment patterns and review of the literature. Urol Oncol, 2014. 32: 826. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24931270/

- Beltran, A.L., et al. Clinicopathological characteristics and outcome of nested carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Virchows Arch, 2014. 465: 199. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24878757/

- Soave, A., et al. Does the extent of variant histology affect oncological outcomes in patients with urothelial carcinoma of the bladder treated with radical cystectomy? Urol Oncol, 2015. 33: 21 e1. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25465301/

- Masson-Lecomte, A., et al. Oncological outcomes of advanced muscle-invasive bladder cancer with a micropapillary variant after radical cystectomy and adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy. World J Urol, 2015. 33: 1087. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25179011/

- Seisen, T., et al. Impact of histological variants on the outcomes of nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer after transurethral resection. Curr Opin Urol, 2014. 24: 524. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25051021/

- Willis, D.L., et al. Clinical outcomes of cT1 micropapillary bladder cancer. J Urol, 2015. 193: 1129. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25254936/

- Kim, H.S., et al. Presence of lymphovascular invasion in urothelial bladder cancer specimens after transurethral resections correlates with risk of upstaging and survival: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Urol Oncol, 2014. 32: 1191. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24954108/

- Tilki, D., et al. Lymphovascular invasion is independently associated with bladder cancer recurrence and survival in patients with final stage T1 disease and negative lymph nodes after radical cystectomy. BJU Int, 2013. 111: 1215. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23181623/

- Martin-Doyle, W., et al. Improving selection criteria for early cystectomy in high-grade t1 bladder cancer: a meta-analysis of 15,215 patients. J Clin Oncol, 2015. 33: 643. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25559810/

- Mari, A., et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of lymphovascular invasion in bladder cancer transurethral resection specimens. BJU Int, 2019. 123: 11. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29807387/

- D, D.A., et al. Accurate prediction of progression to muscle-invasive disease in patients with pT1G3 bladder cancer: A clinical decision-making tool. Urol Oncol, 2018. 36: 239.e1. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29506941/

- Burger, M., et al. Prediction of progression of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer by WHO 1973 and 2004 grading and by FGFR3 mutation status: a prospective study. Eur Urol, 2008. 54: 835. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18166262/

- Fristrup, N., et al. Cathepsin E, maspin, Plk1, and survivin are promising prognostic protein markers for progression in non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Am J Pathol, 2012. 180: 1824. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22449953/

- Palou, J., et al. Protein expression patterns of ezrin are predictors of progression in T1G3 bladder tumours treated with nonmaintenance bacillus Calmette-Guerin. Eur Urol, 2009. 56: 829. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18926620/

- van Rhijn, B.W., et al. The FGFR3 mutation is related to favorable pT1 bladder cancer. J Urol, 2012. 187: 310. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22099989/

- Remy, E., et al. A Modeling Approach to Explain Mutually Exclusive and Co-Occurring Genetic Alterations in Bladder Tumorigenesis. Cancer Res, 2015. 75: 4042. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26238783/

- Dyrskjot, L., et al. Prognostic Impact of a 12-gene Progression Score in Non-muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer: A Prospective Multicentre Validation Study. Eur Urol, 2017. 72: 461. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28583312/

- Marzouka, N.A., et al. A validation and extended description of the Lund taxonomy for urothelial carcinoma using the TCGA cohort. Sci Rep, 2018. 8: 3737. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29487377/

- Ramirez, D., et al. Microscopic haematuria at time of diagnosis is associated with lower disease stage in patients with newly diagnosed bladder cancer. BJU Int, 2016. 117: 783. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26435378/

- Trinh, T.W., et al. Bladder cancer diagnosis with CT urography: test characteristics and reasons for false-positive and false-negative results. Abdom Radiol (NY), 2018. 43: 663. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28677000/

- Nolte-Ernsting, C., et al. Understanding multislice CT urography techniques: Many roads lead to Rome. Eur Radiol, 2006. 16: 2670. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16953373/

- Goessl, C., et al. Is routine excretory urography necessary at first diagnosis of bladder cancer? J Urol, 1997. 157: 480. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8996338/

- Palou, J., et al. Multivariate analysis of clinical parameters of synchronous primary superficial bladder cancer and upper urinary tract tumor. J Urol, 2005. 174: 859. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16093970/

- Holmang, S., et al. Long-term followup of a bladder carcinoma cohort: routine followup urography is not necessary. J Urol, 1998. 160: 45. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9628602/

- Millan-Rodriguez, F., et al. Upper urinary tract tumors after primary superficial bladder tumors: prognostic factors and risk groups. J Urol, 2000. 164: 1183. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10992362/

- Choyke, P.L. Radiologic evaluation of hematuria: guidelines from the American College of Radiology’s appropriateness criteria. Am Fam Physician, 2008. 78: 347. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18711950/

- Hilton, S., et al. Recent advances in imaging cancer of the kidney and urinary tract. Surg Oncol Clin N Am, 2014. 23: 863. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25246053/

- Panebianco, V., et al. Multiparametric Magnetic Resonance Imaging for Bladder Cancer: Development of VI-RADS (Vesical Imaging-Reporting And Data System). Eur Urol, 2018. 74: 294. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29755006/

- Del Giudice, F., et al. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Vesical Imaging-Reporting and Data System (VI-RADS) Inter-Observer Reliability: An Added Value for Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer Detection. Cancers (Basel), 2020. 12. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33076505/

- Yafi, F.A., et al. Prospective analysis of sensitivity and specificity of urinary cytology and other urinary biomarkers for bladder cancer. Urol Oncol, 2015. 33: 66 e25. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25037483/

- Tetu, B. Diagnosis of urothelial carcinoma from urine. Mod Pathol, 2009. 22 Suppl 2: S53. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19494853/

- Raitanen, M.P., et al. Differences between local and review urinary cytology in diagnosis of bladder cancer. An interobserver multicenter analysis. Eur Urol, 2002. 41: 284. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12180229/

- Karakiewicz, P.I., et al. Institutional variability in the accuracy of urinary cytology for predicting recurrence of transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. BJU Int, 2006. 97: 997. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16542342/

- Rosenthal D.L. et al. The Paris System for Reporting Urinary Cytology. 2016, Springer, Zwitzerland. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-319-22864-8

- Cowan, M.L., et al. Improved risk stratification for patients with high-grade urothelial carcinoma following application of the Paris System for Reporting Urinary Cytology. Cancer Cytopathol, 2017. 125: 427. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28272842/

- Meilleroux, J., et al. One year of experience using the Paris System for Reporting Urinary Cytology. Cancer Cytopathol, 2018. 126: 430. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29663682/

- Burton, J.L., et al. Demand management in urine cytology: a single cytospin slide is sufficient. J Clin Pathol, 2000. 53: 718. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11041065/

- Nabi, G., et al. Suspicious urinary cytology with negative evaluation for malignancy in the diagnostic investigation of haematuria: how to follow up? J Clin Pathol, 2004. 57: 365. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15047737/

- Soria, F., et al. An up-to-date catalog of available urinary biomarkers for the surveillance of nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer. World J Urol, 2018. 36: 1981. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29931526/

- Lokeshwar, V.B., et al. Bladder tumor markers beyond cytology: International Consensus Panel on bladder tumor markers. Urology, 2005. 66: 35. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16399415/

- van Rhijn, B.W., et al. Urine markers for bladder cancer surveillance: a systematic review. Eur Urol, 2005. 47: 736. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15925067/

- Lotan, Y., et al. Considerations on implementing diagnostic markers into clinical decision making in bladder cancer. Urol Oncol, 2010. 28: 441. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20610281/

- Liem, E., et al. The Role of Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization for Predicting Recurrence after Adjuvant bacillus Calmette-Guérin in Patients with Intermediate and High Risk Nonmuscle Invasive Bladder Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Individual Patient Data. J Urol, 2020. 203: 283. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31549936/

- Lotan, Y., et al. Evaluation of the Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization Test to Predict Recurrence and/or Progression of Disease after bacillus Calmette-Guérin for Primary High Grade Nonmuscle Invasive Bladder Cancer: Results from a Prospective Multicenter Trial. J Urol, 2019. 202: 920. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31120373/

- Kamat, A.M., et al. Prospective trial to identify optimal bladder cancer surveillance protocol: reducing costs while maximizing sensitivity. BJU Int, 2011. 108: 1119. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21426474/

- Kavalieris, L., et al. Performance Characteristics of a Multigene Urine Biomarker Test for Monitoring for Recurrent Urothelial Carcinoma in a Multicenter Study. J Urol, 2017. 197: 1419. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27986532/

- Beukers, W., et al. FGFR3, TERT and OTX1 as a Urinary Biomarker Combination for Surveillance of Patients with Bladder Cancer in a Large Prospective Multicenter Study. J Urol, 2017. 197: 1410. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28049011/

- Ribal, M.J., et al. Gene expression test for the non-invasive diagnosis of bladder cancer: A prospective, blinded, international and multicenter validation study. Eur J Cancer, 2016. 54: 131. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26761785/

- Critelli, R., et al. Detection of multiple mutations in urinary exfoliated cells from male bladder cancer patients at diagnosis and during follow-up. Oncotarget, 2016. 7: 67435. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27611947/

- Roperch, J.P., et al. Promoter hypermethylation of HS3ST2, SEPTIN9 and SLIT2 combined with FGFR3 mutations as a sensitive/specific urinary assay for diagnosis and surveillance in patients with low or high-risk non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. BMC Cancer, 2016. 16: 704. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27586786/

- Ward, D.G., et al. Multiplex PCR and Next Generation Sequencing for the Non-Invasive Detection of Bladder Cancer. PLoS One, 2016. 11: e0149756. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26901314/

- van der Aa, M.N., et al. Microsatellite analysis of voided-urine samples for surveillance of low-grade non-muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma: feasibility and clinical utility in a prospective multicenter study (Cost-Effectiveness of Follow-Up of Urinary Bladder Cancer trial [CEFUB]). Eur Urol, 2009. 55: 659. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18501499/

- Roupret, M., et al. A comparison of the performance of microsatellite and methylation urine analysis for predicting the recurrence of urothelial cell carcinoma, and definition of a set of markers by Bayesian network analysis. BJU Int, 2008. 101: 1448. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18325051/

- Todenhofer, T., et al. Prognostic relevance of positive urine markers in patients with negative cystoscopy during surveillance of bladder cancer. BMC Cancer, 2015. 15: 155. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25884545/

- Grossman, H.B., et al. Detection of bladder cancer using a point-of-care proteomic assay. JAMA, 2005. 293: 810. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15713770/

- Kim, P.H., et al. Reflex fluorescence in situ hybridization assay for suspicious urinary cytology in patients with bladder cancer with negative surveillance cystoscopy. BJU Int, 2014. 114: 354. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24128299/

- Palou, J., et al. Management of Patients with Normal Cystoscopy but Positive Cytology or Urine Markers. Eur Urol Oncol, 2019. 3: 548. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31331861/

- Roupret, M., et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of MCM5 for the Detection of Recurrence in Nonmuscle Invasive Bladder Cancer Followup: A Blinded, Prospective Cohort, Multicenter European Study. J Urol, 2020. 204: 685. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32314931/

- Valenberg, F., et al. Prospective Validation of an mRNA-based Urine Test for Surveillance of Patients with Bladder Cancer. Eur Urol, 2019. 75: 853. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30553612/

- D’Andrea, D., et al. Diagnostic accuracy, clinical utility and influence on decision-making of a methylation urine biomarker test in the surveillance of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. BJU Int, 2019. 123: 959. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30653818/

- Konety, B., et al. Evaluation of Cxbladder and Adjudication of Atypical Cytology and Equivocal Cystoscopy. Eur Urol, 2019. 76: 238. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31103391/

- Starke, N., et al. Long-term outcomes in a high-risk bladder cancer screening cohort. BJU Int, 2016. 117: 611. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25891519/

- Roobol, M.J., et al. Feasibility study of screening for bladder cancer with urinary molecular markers (the BLU-P project). Urol Oncol, 2010. 28: 686. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21062653/

- Babjuk, M., et al. Urinary cytology and quantitative BTA and UBC tests in surveillance of patients with pTapT1 bladder urothelial carcinoma. Urology, 2008. 71: 718. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18387400/

- van der Aa, M.N., et al. Cystoscopy revisited as the gold standard for detecting bladder cancer recurrence: diagnostic review bias in the randomized, prospective CEFUB trial. J Urol, 2010. 183: 76. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19913254/

- Kurth, K.H., et al. Current methods of assessing and treating carcinoma in situ of the bladder with or without involvement of the prostatic urethra. Int J Urol, 1995. 2 Suppl 2: 8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7553309/

- Krajewski, W., et al. How different cystoscopy methods influence patient sexual satisfaction, anxiety, and depression levels: a randomized prospective trial. Qual Life Res, 2017. 26: 625. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28050795/

- Aaronson, D.S., et al. Meta-analysis: does lidocaine gel before flexible cystoscopy provide pain relief? BJU Int, 2009. 104: 506. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19239453/

- Berajoui, M.B., et al. A Prospective Randomized Controlled Trial of Irrigation “Bag Squeeze” to Manage Pain for Patients Undergoing Flexible Cystoscopy. J Urol, 2020. 204: 1012. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32396409/

- Gunendran, T., et al. Does increasing hydrostatic pressure (“bag squeeze”) during flexible cystoscopy improve patient comfort: a randomized, controlled study. Urology, 2008. 72: 255. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18554699/

- Teoh, J.Y., et al. An International Collaborative Consensus Statement on En Bloc Resection of Bladder Tumour Incorporating Two Systematic Reviews, a Two-round Delphi Survey, and a Consensus Meeting. Eur Urol, 2020. 78: 546. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32389447/

- Suarez-Ibarrola, R., et al. Surgical checklist impact on recurrence-free survival of patients with nonmuscle-invasive bladder cancer undergoing transurethral resection of bladder tumour. BJU Int, 2019. 123: 646. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30248235/

- Anderson, C., et al. A 10-Item Checklist Improves Reporting of Critical Procedural Elements during Transurethral Resection of Bladder Tumor. J Urol, 2016. 196: 1014. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27044571/

- Brausi, M., et al. Variability in the recurrence rate at first follow-up cystoscopy after TUR in stage Ta T1 transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: a combined analysis of seven EORTC studies. Eur Urol, 2002. 41: 523. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12074794/

- Richterstetter, M., et al. The value of extended transurethral resection of bladder tumour (TURBT) in the treatment of bladder cancer. BJU Int, 2012. 110: E76. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22313727/

- Kramer, M.W., et al. En bloc resection of urothelium carcinoma of the bladder (EBRUC): a European multicenter study to compare safety, efficacy, and outcome of laser and electrical en bloc transurethral resection of bladder tumor. World J Urol, 2015. 33: 1937. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25910478/

- Hurle, R., et al. “En Bloc” Resection of Nonmuscle Invasive Bladder Cancer: A Prospective Singlecenter Study. Urology, 2016. 90: 126. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26776561/

- Migliari, R., et al. Thulium Laser Endoscopic En Bloc Enucleation of Nonmuscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer. J Endourol, 2015. 29: 1258. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26102556/

- Zhang, X.R., et al. Two Micrometer Continuous-Wave Thulium Laser Treating Primary Non-MuscleInvasive Bladder Cancer: Is It Feasible? A Randomized Prospective Study. Photomed Laser Surg, 2015. 33: 517. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26397029/

- Mariappan, P., et al. Detrusor muscle in the first, apparently complete transurethral resection of bladder tumour specimen is a surrogate marker of resection quality, predicts risk of early recurrence, and is dependent on operator experience. Eur Urol, 2010. 57: 843. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19524354/

- Taoka, R., et al. Use of surgical checklist during transurethral resection increases detrusor muscle collection rate and improves recurrence-free survival in patients with non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Int J Urol, 2021. 28: 727. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33742465/

- Mariappan, P., et al. Enhanced Quality and Effectiveness of Transurethral Resection of Bladder Tumour in Non-muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer: A Multicentre Real-world Experience from Scotland’s Quality Performance Indicators Programme. Eur Urol, 2020. 78: 520. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32690321/

- Mariappan, P., et al. Good quality white-light transurethral resection of bladder tumours (GQ-WLTURBT) with experienced surgeons performing complete resections and obtaining detrusor muscle reduces early recurrence in new non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: validation across time and place and recommendation for benchmarking. BJU Int, 2012. 109: 1666. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22044434/

- Neumann, E., et al. Transurethral Resection of Bladder Tumors: Next-generation Virtual Reality Training for Surgeons. Eur Urol Focus, 2018. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29802051/

- Bebane, S., et al. Perioperative outcomes of transurethral resection for t1 bladder tumors: quality evaluation based on patient, tumor and surgeon criteria. World J Urol, 2021. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34160681/

- Jancke, G., et al. Impact of surgical experience on recurrence and progression after transurethral resection of bladder tumour in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Scand J Urol, 2014. 48: 276. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24286506/

- Wettstein, M.S., et al. Association between surgical case volume and survival in T1 bladder cancer: A need for centralization of care? Canadian Urol Ass J, 2020. 14: E394. https://cuaj.ca/index.php/journal/article/view/6812

- Bolat, D., et al. Comparing the short-term outcomes and complications of monopolar and bipolar transurethral resection of non-muscle invasive bladder cancers: a prospective, randomized, controlled study. Arch Esp Urol, 2016. 69: 225. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27291558/

- Teoh, J.Y., et al. Comparison of Detrusor Muscle Sampling Rate in Monopolar and Bipolar Transurethral Resection of Bladder Tumor: A Randomized Trial. Ann Surg Oncol, 2017. 24: 1428. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27882470/

- Venkatramani, V., et al. Monopolar versus bipolar transurethral resection of bladder tumors: a single center, parallel arm, randomized, controlled trial. J Urol, 2014. 191: 1703. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24333244/

- Sugihara, T., et al. Comparison of Perioperative Outcomes including Severe Bladder Injury between Monopolar and Bipolar Transurethral Resection of Bladder Tumors: A Population Based Comparison. J Urol, 2014. 192: 1355. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24893311/

- Xu, Y., et al. Comparing the treatment outcomes of potassium-titanyl-phosphate laser vaporization and transurethral electroresection for primary nonmuscle-invasive bladder cancer: A prospective, randomized study. Lasers Surg Med, 2015. 47: 306. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25864416/

- Planelles Gomez, J., et al. Holmium YAG Photocoagulation: Safe and Economical Alternative to Transurethral Resection in Small Nonmuscle-Invasive Bladder Tumors. J Endourol, 2017. 31: 674. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28462594/

- Picozzi, S.C., et al. Is it oncologically safe performing simultaneous transurethral resection of the bladder and prostate? A meta-analysis on 1,234 patients. Int Urol Nephrol, 2012. 44: 1325. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22710969/

- Tsivian, A., et al. Simultaneous transurethral resection of bladder tumor and benign prostatic hyperplasia: hazardous or a safe timesaver? J Urol, 2003. 170: 2241. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14634388/

- Sari Motlagh, R., et al. The recurrence and progression risk after simultaneous endoscopic surgery of urothelial bladder tumour and benign prostatic hyperplasia: a systematic review and metaanalysis. BJU Int, 2021. 127: 143. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32564458/

- van der Meijden, A., et al. Significance of bladder biopsies in Ta,T1 bladder tumors: a report from the EORTC Genito-Urinary Tract Cancer Cooperative Group. EORTC-GU Group Superficial Bladder Committee. Eur Urol, 1999. 35: 267. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10419345/

- Hara, T., et al. Risk of concomitant carcinoma in situ determining biopsy candidates among primary non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer patients: retrospective analysis of 173 Japanese cases. Int J Urol, 2009. 16: 293. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19207607/

- Palou, J., et al. Female gender and carcinoma in situ in the prostatic urethra are prognostic factors for recurrence, progression, and disease-specific mortality in T1G3 bladder cancer patients treated with bacillus Calmette-Guerin. Eur Urol, 2012. 62: 118. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22101115/

- Mungan, M.U., et al. Risk factors for mucosal prostatic urethral involvement in superficial transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. Eur Urol, 2005. 48: 760. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16005563/

- Brant, A., et al. Prognostic implications of prostatic urethral involvement in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. World J Urol, 2019. 37: 2683. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30850856/

- Huguet, J., et al. Cystectomy in patients with high risk superficial bladder tumors who fail intravesical BCG therapy: pre-cystectomy prostate involvement as a prognostic factor. Eur Urol, 2005. 48: 53. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15967252/

- Kausch, I., et al. Photodynamic diagnosis in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a systematic review and cumulative analysis of prospective studies. Eur Urol, 2010. 57: 595. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20004052/

- Mowatt, G., et al. Photodynamic diagnosis of bladder cancer compared with white light cystoscopy: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Technol Assess Health Care, 2011. 27: 3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21262078/

- Neuzillet, Y., et al. Assessment of diagnostic gain with hexaminolevulinate (HAL) in the setting of newly diagnosed non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer with positive results on urine cytology. Urol Oncol, 2014. 32: 1135. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25023786/

- Draga, R.O., et al. Photodynamic diagnosis (5-aminolevulinic acid) of transitional cell carcinoma after bacillus Calmette-Guerin immunotherapy and mitomycin C intravesical therapy. Eur Urol, 2010. 57: 655. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19819064/

- Ray, E.R., et al. Hexylaminolaevulinate fluorescence cystoscopy in patients previously treated with intravesical bacille Calmette-Guerin. BJU Int, 2010. 105: 789. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19832725/

- Chou, R., et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Fluorescent Versus White Light Cystoscopy for Initial Diagnosis or Surveillance of Bladder Cancer on Clinical Outcomes: Systematic Review and MetaAnalysis. J Urol, 2017. 197: 548. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27780784/

- Rolevich, A.I., et al. Results of a prospective randomized study assessing the efficacy of fluorescent cystoscopy-assisted transurethral resection and single instillation of doxorubicin in patients with non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. World J Urol, 2017. 35: 745. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27604374/

- Drejer, D., et al. DaBlaCa-11: Photodynamic Diagnosis in Flexible Cystoscopy-A Randomized Study With Focus on Recurrence. Urology, 2020. 137: 91. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31843623/

- Zheng, C., et al. Narrow band imaging diagnosis of bladder cancer: systematic review and metaanalysis. BJU Int, 2012. 110: E680. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22985502/

- Drejer, D., et al. Clinical relevance of narrow-band imaging in flexible cystoscopy: the DaBlaCa-7 study. Scand J Urol, 2017. 51: 120. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28266904/

- Ye, Z., et al. A comparison of NBI and WLI cystoscopy in detecting non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: A prospective, randomized and multi-center study. Sci Rep, 2015. 5: 10905. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26046790/

- Kim, S.B., et al. Detection and recurrence rate of transurethral resection of bladder tumors by narrow-band imaging: Prospective, randomized comparison with white light cystoscopy. Investig Clin Urol, 2018. 59: 98. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29520385/

- Naito, S., et al. The Clinical Research Office of the Endourological Society (CROES) Multicentre Randomised Trial of Narrow Band Imaging-Assisted Transurethral Resection of Bladder Tumour (TURBT) Versus Conventional White Light Imaging-Assisted TURBT in Primary Non-Muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer Patients: Trial Protocol and 1-year Results. Eur Urol, 2016. 70: 506. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27117749/

- Liem, E., et al. Validation of Confocal Laser Endomicroscopy Features of Bladder Cancer: The Next Step Towards Real-time Histologic Grading. Eur Urol Focus, 2020. 6: 81. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30033066/

- Howard, J.M., et al. Enhanced Endoscopy with IMAGE1 S CHROMA Improves Detection of Nonmuscle Invasive Bladder Cancer During Transurethral Resection. J Endourol, 2021. 35: 647. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33176470/

- Cumberbatch, M.G.K., et al. Repeat Transurethral Resection in Non-muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer: A Systematic Review. Eur Urol, 2018. 73: 925. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29523366/

- Naselli, A., et al. Role of Restaging Transurethral Resection for T1 Non-muscle invasive Bladder Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Eur Urol Focus, 2018. 4: 558. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28753839/

- Elsawy, A.A., et al. Diagnostic performance and predictive capacity of early urine cytology after transurethral resection of nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer: A prospective study. Urol Oncol, 2020. 38: 935.e1. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32654947/

- Elsawy, A.A., et al. Can repeat biopsy be skipped after initial complete resection of T1 bladder cancer? The role of a novel urinary mRNA biomarker. Urol Oncol, 2021. 39: 437.e11. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33785220/

- Grimm, M.O., et al. Effect of routine repeat transurethral resection for superficial bladder cancer: a long-term observational study. J Urol, 2003. 170: 433. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12853793/

- Eroglu, A., et al. The prognostic value of routine second transurethral resection in patients with newly diagnosed stage pT1 non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: results from randomized 10-year extension trial. Int J Clin Oncol, 2020. 25: 698. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31760524/

- Gordon, P.C., et al. Long-term Outcomes from Re-resection for High-risk Non-muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer: A Potential to Rationalize Use. Eur Urol Focus, 2019. 5: 650. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29089252/

- Hashine, K., et al. Results of second transurethral resection for high-grade T1 bladder cancer. Urol Ann, 2016. 8: 10. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26834394/

- Dalbagni, G., et al. Clinical outcome in a contemporary series of restaged patients with clinical T1 bladder cancer. Eur Urol, 2009. 56: 903. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19632765/

- Bishr, M., et al. Tumour stage on re-staging transurethral resection predicts recurrence and progression-free survival of patients with high-risk non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Can Urol Assoc J, 2014. 8: E306. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24940455/

- Palou, J., et al. Recurrence, progression and cancer-specific mortality according to stage at re-TUR in T1G3 bladder cancer patients treated with BCG: not as bad as previously thought. World J Urol, 2018. 36: 1621. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29721611/

- Gontero, P., et al. The impact of re-transurethral resection on clinical outcomes in a large multicentre cohort of patients with T1 high-grade/Grade 3 bladder cancer treated with bacille Calmette-Guerin. BJU Int, 2016. 118: 44. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26469362/

- Baltaci, S., et al. Significance of the interval between first and second transurethral resection on recurrence and progression rates in patients with high-risk non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer treated with maintenance intravesical Bacillus Calmette-Guerin. BJU Int, 2015. 116: 721. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25715815/

- Paner, G.P., et al. Challenges in Pathologic Staging of Bladder Cancer: Proposals for Fresh Approaches of Assessing Pathologic Stage in Light of Recent Studies and Observations Pertaining to Bladder Histoanatomic Variances. Adv Anat Pathol, 2017. 24: 113. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28398951/

- Grignon D., et al. Carcinoma of the Bladder, Histopathology Reporting Guide, 1st Edition. 2018, International Collaboration on Cancer Reporting: Sydney, Australia. http://www.iccr-cancer.org/datasets/published-datasets/urinary-male-genital/bladder

- ICCR. Urinary Tract Carcinoma Biopsy and Transurethral Resection Specimen (TNM8). 2019. [Access date: March 2022]. http://www.iccr-cancer.org/datasets/published-datasets/urinary-male-genital/ut-biopsy-and-tr

Author Correspondence:

Prof. Dr. Semir A. Salim. Al Samarrai

Medical Director of Professor Al Samarrai Medical Center.

Dubai Healthcare City, Al-Razi Building 64, Block D, 2nd Floor, Suite 2018

E-mail: semiralsamarrai@hotmail.com

Tel: +97144233669