Overactive Urinary Bladder

Diagnostic and Evaluation

Comprehensive Review Article

Part 2

Prof. Dr. Semir. A. Salim. Al Samarrai

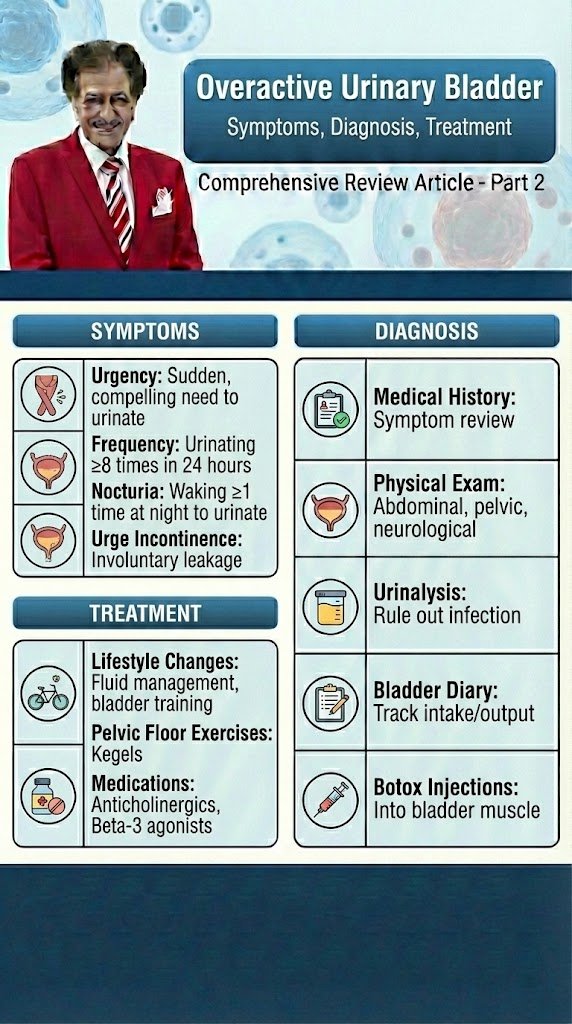

Taking a thorough clinical history is fundamental to the process of clinical evaluation. Despite the lack of high-level evidence to support taking a history, there is universal agreement that it should be the first step in the assessment of anyone with lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). The history should include a full evaluation of LUTS, as well as sexual, gastrointestinal and neurological symptoms. Details of urgency episodes, the type, timing and severity of urinary incontinence (UI), and some attempt to quantify symptoms should also be made. The history should help to categorise LUTS as storage, voiding and post-micturition symptoms, and classify UI as stress urinary incontinence (SUI), urge urinary incontinence (UUI), mixed urinary incontinence (MUI) or overflow incontinence; the latter being defined as “the complaint of UI in the symptomatic presence of an excessively (over-) full bladder (no cause identified)” [1]. The history should also identify patients who need referral to an appropriate clinic/specialist. These may include patients with associated pain, haematuria, history of recurrent urinary tract infection (UTI), pelvic surgery or radiotherapy, constant leakage suggesting a fistula, new-onset enuresis or suspected neurological disease. A neurological, obstetric and gynaecological history may help to understand the underlying cause and identify factors that may affect treatment decisions. Guidance on history-taking and diagnosis in relation to UTIs, neuro-urological conditions and chronic pelvic pain (CPP) can be found in the relevant EAU Guidelines [2,3,4]. Patients should also be asked about other comorbidity as well as smoking status, previous surgical procedures and current medications, as these may affect LUTS. There is little evidence from clinical trials that carrying out a clinical examination improves outcomes, but widespread consensus suggests that clinical examination remains an essential part of assessment of patients with LUTS. Examination should include abdominal examination, to detect an enlarged urinary bladder or other abdominal mass, and digital examination of the vagina and/or rectum. Pelvic examination in women includes assessment of oestrogen status, pelvic floor muscle (PFM) function and careful assessment of any associated pelvic organ prolapse (POP). A cough stress test is necessary to look for stress urinary incontinence (SUI). Among women with genital prolapse, the cough test was found to show good agreement with urodynamic studies (UDS) in the detection of SUI. Urethral mobility can be assessed. Pelvic floor muscle contraction strength can also be assessed digitally. A focused neuro-urological examination should also be routinely undertaken.

Patient questionnaires include symptom scores, symptom questionnaires/scales/indices, patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) and health-related quality of life (QoL) measures. Questionnaires should have been validated for the language in which they are being used, and, if used for outcome evaluation, should have been shown to be sensitive to change. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) published guidance for industry on PROM instruments (questionnaires) in 2009 [5].

Patient bladder diaries include measurement of the frequency and severity of LUTS and is an important step in the evaluation and management of LUT dysfunction. Bladder diaries are a semi-objective method of quantifying symptoms, such as frequency of urinary incontinence (UI) events, number of nocturia episodes, etc. Fluid intake and voided volume measurement can be used to support diagnoses and management planning, for example in overactive bladder (OAB), and for identifying 24-hour or nocturnal polyuria. The optimum number of days required for bladder diaries appears to be based on a balance between accuracy and compliance [6,7]. Diary durations between three and seven days are routinely reported in the literature.

The urinalysis and urinary tract infection investigations are a very important steps in the evaluation and therapy of UTI. Reagent strip (dipstick) urinalysis may indicate proteinuria, haematuria or glycosuria, or suggest UTI requiring further assessment. Urine dipstick testing is a useful adjunct to clinical evaluation in patients in whom urinary symptoms are suspected to be due to UTI. Urinalysis negative for nitrite and leukocyte esterase may exclude bacteriuria in women with LUTS [8], and should be included, with urine culture when necessary, in the evaluation of all patients with LUTS. Urinary incontinence or worsening of LUTS may occur during UTI [9] and existing UI may worsen [10]. The rate and severity of UI were unchanged after eradication of asymptomatic bacteriuria in nursing home residents [11].

The post-void residual volume measurement is also important step in the evaluation and management of OAB and obstruction LUT-Disorders.

Post-void residual (PVR) volume is the amount of urine that remains in the bladder after voiding. It is a measure of voiding efficiency, and results from a number of contributing factors. The detection of significant PVR volume is important because it may worsen symptoms and, more rarely, may be associated with UTI, upper urinary tract (UUT) dilatation and renal insufficiency. Both BOO and/or detrusor underactivity (DU) can potentially contribute to the development of significant PVR volume. Post-void residual volume can be measured by catheterisation or ultrasound (US). Most studies investigating PVR volume have assessed mixed populations including those with neurogenic UI. In general, the data on PVR volume can be applied with caution to women with non-neurogenic LUTS. The results of studies investigating the best method of measuring PVR volume [11-16] have led to the consensus that US measurement of PVR volume is preferable to catheterisation due to its favourable risk–benefit profile. In peri- and postmenopausal women without significant LUTS or pelvic organ symptoms, 95% had a PVR volume < 100 mL [17]. In women with UUI, PVR volume > 100 mL was found in only 10% of cases [18]. Other research has found that a high PVR volume is associated with pelvic organ prolapse (POP), voiding symptoms and an absence of SUI [17, 19–21]. In women with SUI, the mean PVR volume was 39 mL measured by catheterisation and 63 mL measured by US, with 16% of women having PVR volume > 100 mL [22]. Some authors have suggested that it is reasonable to consider a PVR volume > 100 mL to be significant, although many women may remain asymptomatic and hence it is imperative to consider the clinical context [18]. There is no consensus on what constitutes a significant PVR volume in women; therefore, the European Association of urology guidelines panel 2022 suggests the additional use of bladder volume efficiency (BVE). Bladder volume efficiency is the proportion of the total bladder volume that is voided by the patient. Bladder volume efficiency can be calculated as a percentage: BVE = voided volume (VV)/(VV+PVR) × 100. This may be a more reliable parameter to evaluate poor voiding [9].

The Urodynamic testing is widely used as an adjunct to clinical diagnosis, in the belief that it may help to provide or confirm diagnosis, predict treatment outcome or facilitate discussion during counselling. The simplest form of urodynamic evaluation is uroflowmetry. The maximum flow rate (Qmax), the volume voided and the shape of the curve in addition to the PVR volume are the most important aspects to be assessed [23]. The bladder should be sufficiently full because of the volume dependency of Qmax [24, 25]. A minimum voided volume of 150 mL is advised in men, but there is little evidence to suggest a volume threshold in women. It is relevant to ask the patient whether or not the voiding is representative. Invasive urodynamic tests are sometimes performed prior to invasive treatment of LUTS. These tests include multichannel cystometry and pressure–flow studies, ambulatory monitoring and video-urodynamics, and different tests of urethral function, such as urethral pressure profilometry and Valsalva leak point pressure (VLPP). The International Continence Society (ICS) and the United Kingdom Continence Society (UKCS) provide standards to optimise urodynamic test performance and reporting [26, 27]. A characteristic of a good urodynamic study is that the patient’s symptoms are replicated, recordings are checked for quality control, and results interpreted in the context of the clinical problem, remembering that there may be physiological variability within the same individual [26]. Non-invasive alternatives for measurement of detrusor pressure and BOO include transabdominal wall near-infrared spectroscopy and US detrusor wall thickness analysis, but as yet, these techniques have not been adopted into routine clinical practice [23].

The diagnostic accuracy investigation may provide an important information of degree of OAB. A pressure–flow study, that is, the simultaneous measurement of flow rate and detrusor pressure during voiding, can reveal whether a poor flow rate and PVR volume are due to BOO, poor bladder contraction strength/detruser underactivity (DU), or a combination of both. Also, it may provide information on the degree of pelvic floor relaxation and thus diagnose dysfunctional voiding. Several proposals to define BOO in women have been made. These definitions are based on detrusor pressure, either PdetQmax or the maximum value Pdet.max, and the Qmax value, either during the pressure–flow study or during uroflowmetry. These measures are sometimes combined with the findings during fluoroscopic imaging [28, 29]. Unlike the situation in men, there is no widely accepted threshold for BOO diagnosis in women. Bladder contraction strength parameters are derived from detrusor pressure and flow rate during a pressure–flow study or from stop tests [29], but again, validation is poor. Although these parameters estimate the strength of the contraction, they ignore its speed and persistence [30]. A video-urodynamic study can be useful to detect the site of obstructed voiding, which may be anatomical or functional [31]. Also, videourodynamics may detect bladder diverticulum or gross reflux as a pressure-absorbing reservoir.

The predictive value of urethral function tests remains unclear. In observational studies, there was no consistent correlation between the results of these tests and subsequent success or failure of SUI surgery [32-34, 35]. The same was true in a secondary analysis of an RCT [36]. The presence of preoperative detrusor overactivity (DO) in women with stress-predominant MUI has been associated with postoperative UUI but did not predict overall treatment failure following mid-urethral sling (MUS) surgery or colpo-suspension [36]. The urodynamic diagnosis of DO had no predictive value for treatment response in studies on antimuscarinics, onabotulinumtoxinA and sacral nerve stimulation in patients with OAB symptoms [37, 38]. Augmentation cystoplasty aims to abolish DO, improve bladder compliance and increase functional bladder capacity but there is no evidence to guide whether or not preoperative urodynamics are predictive of outcome. Most clinicians would, however, consider preoperative urodynamics as essential prior to contemplating augmentation cystoplasty. A pressure–flow study is capable of discriminating BOO from DU as a cause of voiding dysfunction. The predictive value of parameters derived from such a study for voiding dysfunction after a surgical procedure for SUI is however low. A low preoperative flow rate and a low detrusor voiding pressure have been shown to correlate with voiding dysfunction after a tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) and an autologous fascial sling procedure, respectively [39-41]. Bladder contraction strength parameters combining flow rate and detrusor pressure only poorly predicted voiding dysfunction after autologous fascial sling [42]. Post hoc analysis of two high-quality surgical trials of TVT, Burch colpo-suspension and autologous fascial sling showed that no preoperative urodynamic parameter predicted postoperative voiding dysfunction in a selected population of women with low preoperative PVR volume [43, 44]. The European Association of Urology Guidelines Panel 2023 recognises that it may be valuable to use urodynamic test results to select the optimum management strategy; however, there is inconsistent evidence regarding the predictive value of such tests. When urodynamics and clinical assessment (i.e., by history and examination) are in disagreement, there needs to be a careful re-evaluation of the clinical symptoms and investigation results to ensure that the diagnosis is correct before invasive treatments are contemplated. Expert opinion recognises urodynamic testing as the most comprehensive analysis of LUT function. The primary aim of urodynamics includes reproduction of the patient’s symptoms. The information one obtains from urodynamics may be very valuable to discuss and manage expectation regarding invasive treatment.

The pad testing for measurement of urine loss using an absorbent pad worn over a set period of time or during a protocol of physical exercise can be used to quantify the presence and severity of UI, as well as provide an objective evidence of response to treatment. The clinical utility of pad tests in woman with UI has been assessed in two SRs [45, 46]. A 1-hour pad test using a standardised exercise protocol and a diagnostic threshold of 1.4 g shows good specificity but lower sensitivity for symptoms of SUI and MUI. A 24-hour pad test using a threshold of 4.4 g is more reproducible but is difficult to standardise, with variation according to activity level [47].

The imaging investigations are an important steps in the diagnosis and management of LUT-Dysfunction.

Imaging improves our understanding of the anatomical and functional abnormalities that may cause LUTS. In clinical practice, imaging is used to understand the relationship between anatomy and function. Ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have largely replaced x-ray imaging in the evaluation of the pelvic floor. Ultrasound is sometimes preferred to MRI because of its ability to produce three-dimensional (3D) and 4D (dynamic) images at lower cost and wider availability. There is no need for UUT imaging unless a high-pressure bladder, severe POP or chronic urinary retention is suspected or diagnosed, or abnormal renal function tests are observed. In cases of suspected UI caused by an UUT anomaly or uretero-vaginal fistula, UUT imaging (urography, computed tomography [CT]) may be indicated [48].

The ultrasonography of the LUT plays a role in the differential diagnosis of women with LUTS and in cases presenting with haematuria. Ultrasonography has been used in the evaluation of UI and pelvic floor since the 1980s. Different imaging approaches, such as abdominal, transvaginal, transrectal, perineal and transurethral are described. The bladder neck and urethra are easily visible and measurements can be done at rest and during straining, coughing and pelvic floor contraction. The parameters assessed in the diagnosis of SUI, for example, include bladder neck mobility or descent, urethro-vesical angle and urethral rotation [49, 50]. Ultrasonography can be used to assess PFMs and their function. Contraction of PFM results in displacement of pelvic structures that can easily be imaged on US. Integrity of the levator ani muscle can be determined by 3D transperineal US. Ultrasound may also provide information on the anatomical changes of the LUT and pelvic floor associated with persistence of symptoms post-treatment [51]. The specific role of US is discussed in the condition-specific sections of these guidelines where applicable.

The detrusor wall thickness measurement is as well very important step in the diagnosis and management of LUT-Dysfunction.

As OAB syndrome is linked to DO, it has been hypothesised that frequent detrusor contractions may increase detrusor/bladder wall thickness (DWT/BWT). Transvaginal US seems to be more accurate with less interobserver variability than transabdominal and transperineal approaches [52]. Several cut-off points have been suggested, from 4.4 to 6.5 mm. Other studies are contradictory and did not find this correlation. No consensus exists as to the relationship between OAB and increased BWT/DWT [53], and there is no evidence that BWT/ DWT imaging improves management of OAB. There is no widely accepted, standardised bladder volume for bladder wall thickness measurement. In a retrospective study including 227 women with symptoms of voiding difficulty (hesitancy, intermittency and poor stream), 74 (32.6%) were diagnosed with voiding dysfunction on the basis of free uroflowmetry and residual urine. While controlling for the effect of DO, the relationships between DWT and different parameters of voiding function in pressure–flow studies and free uroflowmetry were examined. The results indicated that DWT was not associated with any urodynamic parameters that may indicate BOO [54]. The magnetic resonance imaging is as well an important step in diagnosis and therapy of LUT-Dysfunction.

There is a general consensus that MRI provides good global pelvic floor assessment, including POP, defecatory function and integrity of the pelvic floor support [55]. However, there is a large variation in MRI interpretation between observers [56] and little evidence to support its clinical usefulness in the management of LUTS/UI. There is no conclusive evidence that MRI evaluation of POP is more clinically useful than vaginal examination. Studies have assessed the use of imaging to assess the mechanism of MUS insertion for SUI. One study suggested that MUS placement decreased mobility of the mid-urethra but not of the bladder neck [57]. Following MUS, a wider gap between pubic symphysis and sling (assessed by imaging) has been shown to correlate with a lower chance of cure of SUI [58].

The role of urinary biomarkers and microbiome in the diagnosis of LUT-Dysfunction has increased in recent years. Nerve growth factor (NGF), brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), prostaglandin E2, adenosin triphosphate (ATP) and purinergic receptors (P2X) in bladder tissue have been studied as biomarkers for OAB. Serum beta natriuretic peptide (BNP), urinary 6-sulfatoxymelatonin and C-reactive protein (CRP), melatonin, vasopressin levels have been studied in relation to nocturia. For SUI, urinary IL 12-70, urinary NGF, N-telopeptide of type I collagen (NTx) and urinary microbiome have been studied. Another area of discovery is the role of urinary microbiome in identifying and differentiating various types of UI and other LUT disease in women. A SR described studies showing differences in the types and relative proportions of bacteria such as Lactobacillus, Gardnerella, and Atopobium vaginae, among women with different types of UI compared with healthy controls.

REFERENCES:

1. D’Ancona, C., et al. The International Continence Society (ICS) report on the terminology for adult

male lower urinary tract and pelvic floor symptoms and dysfunction. Neurourol Urodyn, 2019. 38: 433.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30681183/

2. Blok, B., et al. EAU Guidelines on Neuro-urology. Edn. presented at the 37th EAU Annual Congress

Amsterdam. 2022, EAU Guidelines Office, Arnhem, The Netherlands.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19403235/

3. Bonkat, G., et al. EAU Guidelines on Urological Infections. Edn. presented at the 37th EAU Annual

Congress Amsterdam. 2022, EAU Guidelines Office, Arnhem, The Netherlands.

https://uroweb.org/guideline/urological-infections/

4. Engeler, D., et al. EAU Guidelines on Chronic Pelvic Pain. Edn. presented at the 37th EAU Annual

Congress Amsterdam. 2022, EAU Guidelines Office, Arnhem, The Netherlands.

https://uroweb.org/guideline/chronic-pelvic-pain/

5. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, F.a.D.A. Guidance for Industry – Patient-Reported

Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims. 2009.

[access data March 2022].

https://www.fda.gov/media/77832/download

6. Yap, T.L., et al. A systematic review of the reliability of frequency-volume charts in urological

research and its implications for the optimum chart duration. BJU Int, 2007. 99: 9.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16956355/

7. Bright, E., et al. Urinary diaries: evidence for the development and validation of diary content,

format, and duration. Neurourol Urodyn, 2011. 30: 348.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21284023/

8. Buchsbaum, G.M., et al. Utility of urine reagent strip in screening women with incontinence for

urinary tract infection. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct, 2004. 15: 391.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15278254/

9. Arinzon, Z., et al. Clinical presentation of urinary tract infection (UTI) differs with aging in women.

Arch Gerontol Geriatr, 2012. 55: 145.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21963175/

10. Moore, E.E., et al. Urinary incontinence and urinary tract infection: temporal relationships in

postmenopausal women. Obstet Gynecol, 2008. 111: 317.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18238968/

11. Ouslander, J.G., et al. Does eradicating bacteriuria affect the severity of chronic urinary incontinence

in nursing home residents? Ann Intern Med, 1995. 122: 749.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7717597/

12. Griffiths, D.J., et al. Variability of post-void residual urine volume in the elderly. Urol Res, 1996. 24: 23.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8966837/

13. Marks, L.S., et al. Three-dimensional ultrasound device for rapid determination of bladder volume.

Urology, 1997. 50: 341.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9301695/

14. Nygaard, I.E. Postvoid residual volume cannot be accurately estimated by bimanual examination. Int

Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct, 1996. 7: 74.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8798090/

15. Ouslander, J.G., et al. Use of a portable ultrasound device to measure post-void residual volume

among incontinent nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc, 1994. 42: 1189.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7963206/

16. Stoller, M.L., et al. The accuracy of a catheterized residual urine. J Urol, 1989. 141: 15.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2908944/

17. Gehrich, A., et al. Establishing a mean postvoid residual volume in asymptomatic perimenopausal

and postmenopausal women. Obstet Gynecol, 2007. 110: 827.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17906016/

18. Robinson, D., et al. Defining female voiding dysfunction: ICI-RS 2011. Neurourol Urodyn, 2012. 31: 313.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22415792/

19. Haylen, B.T., et al. Immediate postvoid residual volumes in women with symptoms of pelvic floor

dysfunction. Obstet Gynecol, 2008. 111: 1305.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18515513/

20. Lukacz, E.S., et al. Elevated postvoid residual in women with pelvic floor disorders: prevalence and

associated risk factors. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct, 2007. 18: 397.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16804634/

21. Milleman, M., et al. Post-void residual urine volume in women with overactive bladder symptoms.

J Urol, 2004. 172: 1911.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15540753/

22. Tseng, L.H., et al. Postvoid residual urine in women with stress incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn,

2008. 27: 48.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17563112/

23. Rosier, P.F.W.M. et al. Committee 6. Urodynamic testing, In: Incontinence, P. Abrams, L. Cardozo, A.

Wagg, A. Wein, Eds. 2017, CI-ICS. International Continence Society: Bristol UK.

https://www.ics.org/publications/ici_6/Incontinence_6th_Edition_2017_eBook_v2.pdf

24. Siroky, M.B., et al. The flow rate nomogram: I. Development. J Urol, 1979. 122: 665.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/159366/

25. Haylen, B.T., et al. Maximum and average urine flow rates in normal male and female populations–

the Liverpool nomograms. Br J Urol, 1989. 64: 30.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2765766/

26. Rosier, P., et al. International Continence Society Good Urodynamic Practices and Terms 2016:

Urodynamics, uroflowmetry, cystometry, and pressure-flow study. Neurourol Urodyn, 2017. 36: 1243.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27917521/

27. Abrams, P., et al. United Kingdom Continence Society: Minimum standards for urodynamic studies,

2018. Neurourol Urodyn, 2019. 38: 838.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30648750/

28. Pang, K.H., et al. Diagnostic Tests for Female Bladder Outlet Obstruction: A Systematic Review

from the European Association of Urology Non-neurogenic Female LUTS Guidelines Panel. Eur Urol

Focus, 2021. S2405: 00231.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34538750/

29. Rademakers, K., et al. Recommendations for future development of contractility and obstruction

nomograms for women. ICI-RS 2014. Neurourol Urodyn, 2016. 35: 307.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26872573/

30. Osman, N.I., et al. Detrusor underactivity and the underactive bladder: a new clinical entity? A

review of current terminology, definitions, epidemiology, aetiology, and diagnosis. Eur Urol, 2014.

65: 389.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24184024/

31. Nitti, V.W., et al. Diagnosing bladder outlet obstruction in women. J Urol, 1999. 161: 1535.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10210391/

32. Homma, Y., et al. Assessment of overactive bladder symptoms: comparison of 3-day bladder diary

and the overactive bladder symptoms score. Urology, 2011. 77: 60.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20951412/

33. Stav, K., et al. Women overestimate daytime urinary frequency: the importance of the bladder diary.

J Urol, 2009. 181: 2176.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19296975/

34. van Brummen, H.J., et al. The association between overactive bladder symptoms and objective

parameters from bladder diary and filling cystometry. Neurourol Urodyn, 2004. 23: 38.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14694455/

35. Gravas, S., et al. EAU Guidelines on the management of Non-neurogenic Male LUTS. Edn. presented

at the 37th EAU Annual Congress Amsterdam. 2022, EAU Guidelines Office, Arnhem, The Netherlands.

https://uroweb.org/guideline/treatment-of-non-neurogenic-male-luts/

36. Nager, C.W., et al. Baseline urodynamic predictors of treatment failure 1 year after mid urethral sling

surgery. J Urol, 2011. 186: 597.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21683412/

37. Lin, F.C., et al. The Role of Urodynamic Testing Prior to Third-Line OAB Therapy. Curr Bladder Dysf

Rep, 2020. 15: 159.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/341978617

38. Nitti, V.W., et al. Response to fesoterodine in patients with an overactive bladder and urgency

urinary incontinence is independent of the urodynamic finding of detrusor overactivity. BJU Int,

2010. 105: 1268.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19889062/

39. Dawson, T., et al. Factors predictive of post-TVT voiding dysfunction. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor

Dysfunct, 2007. 18: 1297.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17347790/

40. Hong, B., et al. Factors predictive of urinary retention after a tension-free vaginal tape procedure for

female stress urinary incontinence. J Urol, 2003. 170: 852.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12913715/

41. Miller, E.A., et al. Preoperative urodynamic evaluation may predict voiding dysfunction in women

undergoing pubovaginal sling. J Urol, 2003. 169: 2234.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12771757/

42. Groen, J., et al. Bladder contraction strength parameters poorly predict the necessity of long-term

catheterization after a pubovaginal rectus fascial sling procedure. J Urol, 2004. 172: 1006.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15311024/

43. Abdel-Fattah, M., et al. Pelvicol pubovaginal sling versus tension-free vaginal tape for treatment of

urodynamic stress incontinence: a prospective randomized three-year follow-up study. Eur Urol,

2004. 46: 629.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15474274/

44. Lemack, G.E., et al. Normal preoperative urodynamic testing does not predict voiding dysfunction

after Burch colposuspension versus pubovaginal sling. J Urol, 2008. 180: 2076.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18804239/

45. Al Afraa, T., et al. Normal lower urinary tract assessment in women: I. Uroflowmetry and post-void

residual, pad tests, and bladder diaries. Int Urogynecol J, 2012. 23: 681.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21935667/

46. Krhut, J., et al. Pad weight testing in the evaluation of urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn, 2014.

33: 507.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23797972/

47. Painter, V., et al. Does patient activity level affect 24-hr pad test results in stress-incontinent

women? Neurourol Urodyn, 2012. 31: 143.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21780173/

48. Khullar, V., et al. , Committee 7 Imaging, neurophysiological testing and other tests, In: Incontinence

P. Abrams, L. Cardozo, A. Wagg, A. Wein, Eds, 2017, ICI-ICS. International Continence Society:

Bristol, UK.

https://www.ics.org/publications/ici_6/Incontinence_6th_Edition_2017_eBook_v2.pdf

49. Deng, S., et al. ROC analysis and significance of transperineal ultrasound in the diagnosis of stress

urinary incontinence. J Med Imaging Health Info, 2020. 10: 113.

https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/asp/jmihi/2020/00000010/00000001/art00019;jsessionid=

2kc469smid7os.x-ic-live-02

50. Keshavarz, E., et al. Prediction of Stress Urinary Incontinence Using the Retrovesical (beta) Angle in

Transperineal Ultrasound. J Ultrasound Med, 2021. 40: 1485.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33035377/

51. Illiano, E., et al. Translabial ultrasound: a non-invasive technique for assessing “technical errors”

after TOT failure. Int Urogynecol J, 2021.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34191103/

52. Panayi, D.C., et al. Transvaginal ultrasound measurement of bladder wall thickness: a more reliable

approach than transperineal and transabdominal approaches. BJU Int, 2010. 106: 1519.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20438565/

53. Antunes-Lopes, T., et al. Biomarkers in lower urinary tract symptoms/overactive bladder: a critical

overview. Curr Opin Urol, 2014. 24: 352.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24841379/

54. Lekskulchai, O., et al. Is detrusor hypertrophy in women associated with voiding dysfunction? Aust

N Z J Obstet Gynaecol, 2009. 49: 653.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20070717/

55. Woodfield, C.A., et al. Imaging pelvic floor disorders: trend toward comprehensive MRI. AJR Am

J Roentgenol, 2010. 194: 1640.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20489108/

56. Lockhart, M.E., et al. Reproducibility of dynamic MR imaging pelvic measurements: a multiinstitutional

study. Radiology, 2008. 249: 534.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18796659/

57. Shek, K.L., et al. The urethral motion profile before and after suburethral sling placement. J Urol,

2010. 183: 1450.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20171657/

58. Chantarasorn, V., et al. Sonographic appearance of transobturator slings: implications for function

and dysfunction. Int Urogynecol J, 2011. 22: 493.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20967418/

Author Correspondence:

Prof. Dr. Semir A. Salim. Al Samarrai

Medical Director of Professor Al Samarrai Medical Center.

Dubai Healthcare City, Al-Razi Building 64, Block D, 2nd Floor, Suite 2018

E-mail: semiralsamarrai@hotmail.com

Tel: +97144233669