Prostate Cancer

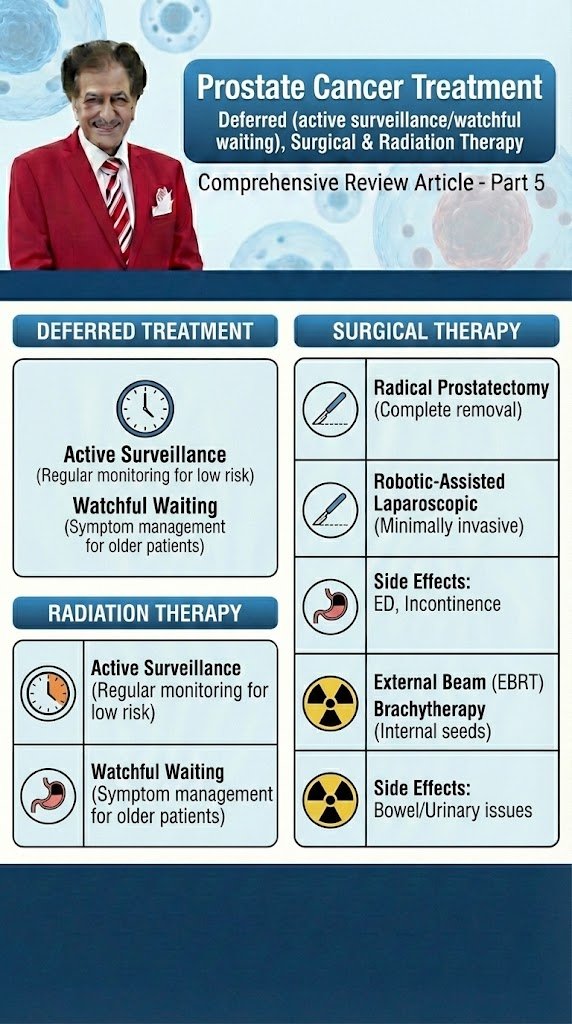

Treatment

Deferred (active surveillance/watchful waiting), Surgical & Radiation Therapy

Comprehensive Review Article

Part 5

Prof. Dr. Semir. A. Salim. Al Samarrai

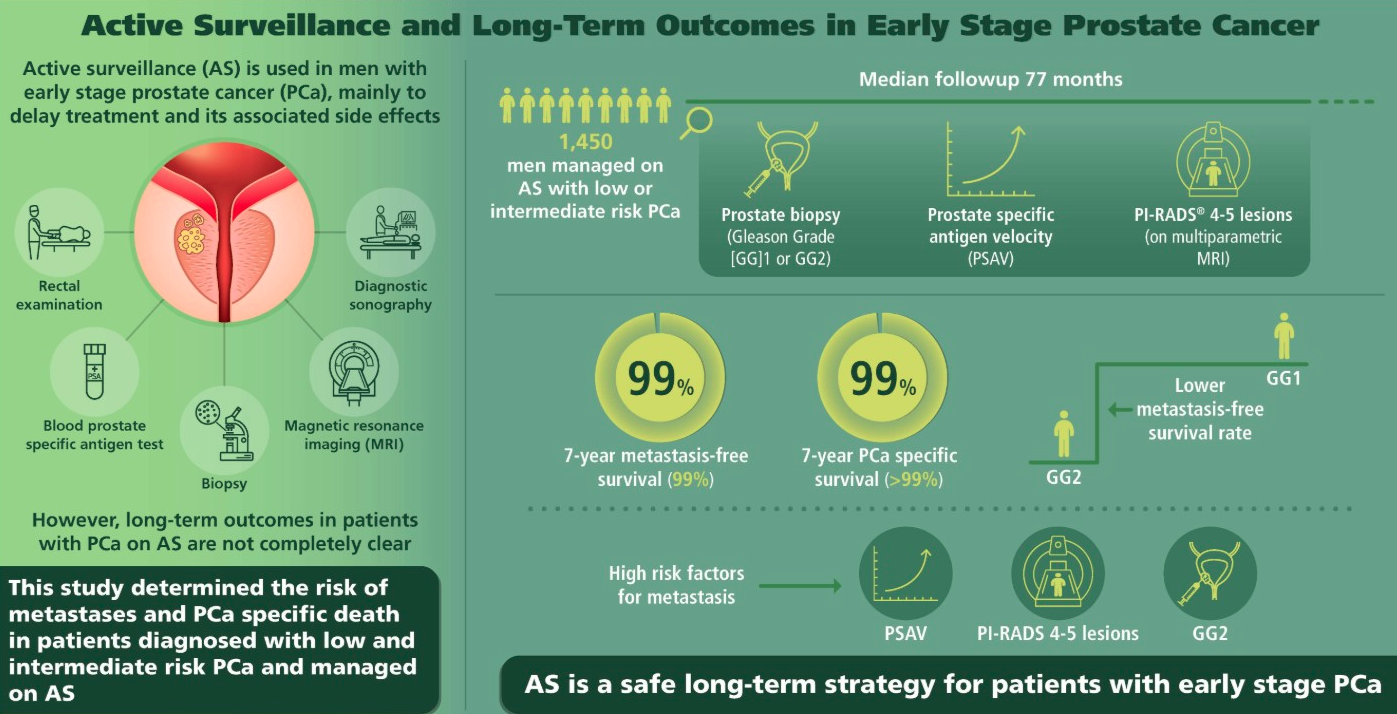

Figure 1. Active Surveillance and Long-Term Outcomes in Early Stage Prostate Cancer

Treatment modalities:

The treatment modalities contain different criterias, after first modality in the deferred treatment (active surveillance/watchful waiting).

- Deferred treatment (active surveillance/watchful waiting)

In localised disease a life expectancy of at least 10 years is considered mandatory for any benefit from active treatment. Data are available on patients who did not undergo local treatment with up to 25 years of

follow-up, with endpoints of overall survival (OS) and cancer specific survival (CSS). Several series have shown a consistent CSS rate of 82–87% at 10 years [1–6], and 80–95% for T1/T2 and ISUP grade < 2 PCas [512]. In three studies with data beyond 15 years, the DSS was 80%, 79% and 58% [3,5,6], and two reported 20-year CSS rates of 57% and 32%, respectively [3,5]. The observed heterogeneity in outcomes is due to differences in inclusion criteria, with some older studies from the pre-PSA era showing worse outcomes [5]. In addition, many patients classified as ISUP grade 1 would now be classified as ISUP grade 2–3 based on the 2005 Gleason classification, suggesting that the above-mentioned results should be considered as minimal. Patients with well-, moderately- and poorly differentiated tumours had 10-year CSS rates of 91%, 90% and 74%, respectively, correlating with data from the pooled analysis [7]. Observation was most effective in men aged 65–75 years with low-risk PCa [8].

Co-morbidity is as important as age in predicting life expectancy in men with PCa. Increasing co-morbidity greatly increases the risk of dying from non-PCa-related causes and for those men with a short life expectancy.

In an analysis of 19,639 patients aged > 65 years who were not given curative treatment, most men with a CCI score > 2 had died from competing causes at 10 years follow-up regardless of their age at time of diagnosis.

Tumour aggressiveness had little impact on OS suggesting that patients could have been spared biopsy and diagnosis of cancer. Men with a CCI score < 1 had a low risk of death at 10 years, especially for well or moderately-differentiated lesions [9]. This highlights the importance of assessing co-morbidity before considering a biopsy.

In screen-detected localised PCa the lead-time bias is likely to be greater. Mortality from untreated screen-detected PCa in patients with ISUP grade 1–2 might be as low as 7% at 15 years follow-up [10].

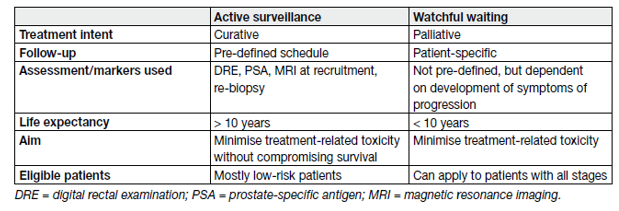

Consequently, approximately 45% of men with PSA-detected PCa are suitable for close follow-up through a robust surveillance programme. There are two distinct strategies for conservative management that aim to reduce over-treatment: AS and WW (Table 1).

Table 1. Definitions of active surveillance and watchful waiting

- Active surveillance

Active surveillance aims to avoid unnecessary treatment in men with clinically localised PCa who do not require immediate treatment, but at the same time achieve the correct timing for curative treatment in those who eventually do [11]. Patients remain under close surveillance through structured surveillance programmes with regular follow-up consisting of PSA testing, clinical examination, MRI imaging and repeat prostate biopsies, with curative treatment being prompted by pre-defined thresholds indicative of potentially life-threatening disease, which is still potentially curable, while considering individual life expectancy.

Watchful waiting refers to conservative management for patients deemed unsuitable for curative treatment from the outset, and patients are clinically ‘watched’ for the development of local or systemic progression with (imminent) disease-related complaints, at which stage they are then treated palliatively according to their symptoms in order to maintain QoL.

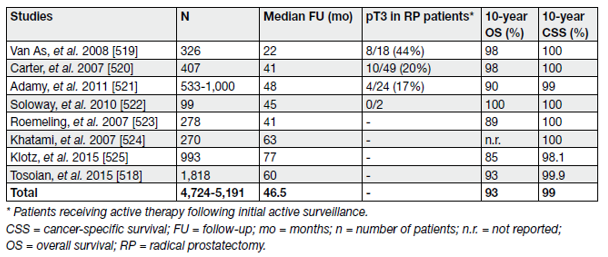

Several cohorts have investigated AS in organ-confined disease, the findings of which were summarised in a systematic review [12]. More recently, the largest prospective series of men with low-risk PCa managed by AS was published [13]. Table 2 summarises the results of selective AS cohorts.

Table 2. Active surveillance in screening-detected prostate cancer (large cohorts with longer-term follow-up)

It is clear that the long-term OS and CSS of patients on AS are extremely good. However, more than one-third of patients are ‘reclassified’ during follow-up, most of whom undergo curative treatment due to disease upgrading, increase in disease extent, disease stage, progression or patient preference.

- Watchful waiting

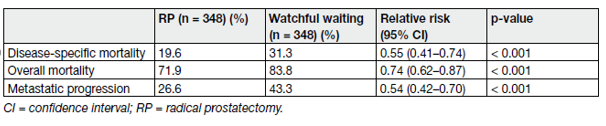

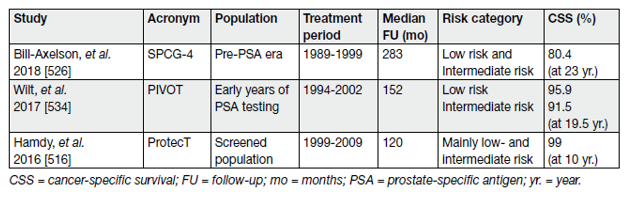

The Outcome of watchful waiting compared with active treatment showed the SPCG-4 study which was a RCT from the pre-PSA era, randomising patients to either WW or RP (Table 3) [14].

Table 3. Outcome of SPCG-4 at a median follow-up of 23.6 years

The study found radical prostatectomy (RP) to provide superior cancer-specific survival (CSS), overall survival (OS) and biochemical progression-free survival (PFS) compared to watchful waiting (WW) at a median follow-up of 23.6 years (range 3 weeks–28 years).

The overall evidence indicates that for men with asymptomatic, clinically localised PCa and with a life expectancy of < 10 years based on co-morbidities and/or age, the oncological advantages of active treatment over WW are unlikely to be relevant to them. Consequently, WW should be adopted for such patients.

- Radical Prostatectomy

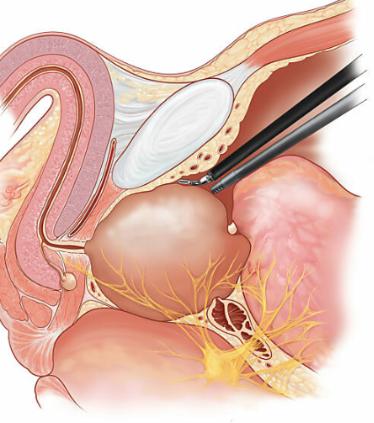

The second treatment modality with radical prostatectomy showed that the goal of RP by any approach is the eradication of cancer while, whenever possible, preserving pelvic organ function [15]. The procedure involves removing the entire prostate with its capsule intact and SVs, followed by vesico-urethral anastomosis. Surgical approaches have expanded from perineal and retropubic open approaches to laparoscopic and robotic-assisted techniques; anastomoses have evolved from Vest approximation sutures to continuous suture watertight anastomoses under direct vision and mapping of the anatomy of the dorsal venous complex (DVC) and cavernous nerves has led to excellent visualisation and potential for preservation of erectile function [16]. The main results from multi-centre RCTs involving RP are summarised in Table 4.

Table 4. Oncological results of radical prostatectomy in organ-confined disease in RCTs

Pre-operative preparation:

- Pre-operative patient education

As before any surgery appropriate education and patient consent is mandatory prior to RP. Peri-operative education has been shown to improve long-term patient satisfaction following RP [17]. Augmentation of standard verbal and written educational materials such as use of interactive multimedia tools [18,19] and pre-operative patient-specific 3D printed prostate models has been shown to improve patient understanding and satisfaction and should be considered to optimise patient-centred care [20].

- Pre-operative pelvic floor exercises

Although many patients who have undergone RP will experience a return to urinary continence [21], temporary urinary incontinence is common early after surgery, reducing QoL. Pre-operative pelvic floor exercises (PFE) with, or without, biofeedback have been used with the aim of reducing this early post-operative incontinence.

A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect of pre-RP PFE on post-operative urinary incontinence showed a significant improvement in incontinence rates at 3 months post-operatively with an OR of 0.64 (p = 0.005), but not at 1 month or 6 months [22]. Pre-operative PFE may therefore provide some benefit, however the analysis was hampered by the variety of PFE regimens and a lack of consensus on the definition of incontinence.

- Prophylactic antibiotics

Prophylactic antibiotics should be used; however, no high-level evidence is available to recommend specific prophylactic antibiotics prior to RP (See EAU Urological Infections Guidelines [23]). In addition, as the susceptibility of bacterial pathogens and antibiotic availability varies worldwide, any use of prophylactic antibiotics should adhere to local guidelines.

- Neoadjuvant androgen deprivation therapy

Several RCTs have analysed the impact of neoadjuvant ADT before RP, most of these using a 3-month period. The main findings were summarised in a Cochrane review [24]. Neoadjuvant ADT is associated with a decreased rate of pT3 (downstaging), decreased positive margins, and a lower incidence of positive LNs.

These benefits are greater with increased treatment duration (up to 8 months). However, since neither the PSA relapse-free survival nor CSS were shown to improve, neoadjuvant ADT should not be considered as standard clinical practice.

- Surgical techniques

Prostatectomy can be performed by open-, laparoscopic- or robot-assisted (RARP) approaches. The initial open technique of RP described by Young in 1904 was via the perineum [16] but suffered from a lack of access to pelvic LNs. If lymphadenectomy is required during perineal RP it must be done via a separate open retropubic (RRP) or laparoscopic approach. The open retropubic approach was popularised by Walsh

in 1982 following his anatomical description of the DVC, enabling its early control and of the cavernous nerves, permitting a bilateral nerve-sparing procedure [25]. This led to the demise in popularity of perineal

RP and eventually to the first laparoscopic RP reported in 1997 using retropubic principles, but performed transperitoneally [26]. The initial 9 cases averaged 9.4 hours, an indication of the significant technical and ergonomic difficulties of the technique. Most recently, RARP was introduced using the da Vinci Surgical SystemR by Binder in 2002 [27]. This technology combined the minimally-invasive advantages of laparoscopic RP with improved surgeon ergonomics and greater technical ease of suture reconstruction of the vesicourethral anastomosis and has now become the preferred minimally-invasive approach, when available.

In a randomised phase III trial, RARP was shown to have reduced admission times and blood loss, but not earlier (12 weeks) functional or oncological outcomes compared to open RP [28]. An updated analysis with follow-up at 24 months did not reveal any significant differences in functional outcomes between the approaches [29].

A systematic review and meta-analysis of non-RCTs demonstrated that RARP had lower peri-operative morbidity and a reduced risk of positive surgical margins compared with laparoscopic prostatectomy (LRP), although there was considerable methodological uncertainty [30]. There was no evidence of differences in urinary incontinence at 12 months and there was insufficient evidence to draw conclusions based on differences in cancer-related, patient-driven or ED outcomes.

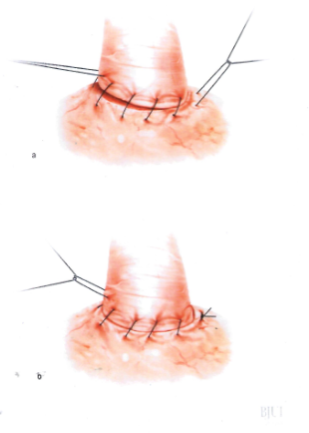

- Robotic anterior versus Retzius-sparing dissection

Robot-assisted RP has typically been performed via the anterior approach, first dropping the bladder to expose the space of Retzius. However, the posterior approach (Retzius-sparing [RS-RARP]) has been used to minimise injury to support structures surrounding the prostate.

Galfano et al., first described RS-RARP in 2010 [31]. This approach commences dissection posteriorly at the pouch of Douglas, first dissecting the SVs and progressing caudally behind the prostate.

All of the anterior support structures are avoided, giving rise to the hypothetical mechanism for improved early post-operative continence. Retzius-sparing-RARP thus offers the same potential advantage as the open perineal approach, but without disturbance of the perineal musculature.

Figure 2. Robotic Assisted Prostatectomy

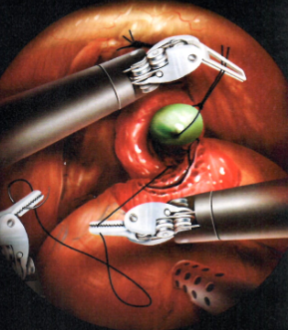

Retzius-sparing-RARP )RS-RARP( has been recently investigated in RCTs leading to four systematic reviews and metaanalyses [32–34] including a 2020 Cochrane systematic review [35] and a large propensity score matched analysis [36]. The Cochrane review used the most rigorous methodology and analysed 5 RCTs with 502 patients. It found with moderate certainty that RS-RARP improved continence at 1 week post catheter removal compared to standard RARP (RR: 1.74). Continence may also be improved at 3 months post-operatively (RR: 1.33), but this was based on low-certainty data. Continence outcomes appeared to equalise by 12 months (RR: 1.01). These findings matched those of the other systematic reviews. However, a significant concern was that RS-RARP appears to increase the risk of positive margins (RR: 1.95) but this was also low-certainty evidence. A single-surgeon propensity score matched analysis of 1,863 patients reached the same conclusion as the systematic reviews regarding earlier return to continence but did not show data on margin status [36].

Based on these data, recommendations cannot be made for one technique over another. However, the trade-offs between the risks of a positive margin vs. earlier continence recovery should be discussed with prospective patients. Furthermore, no high-level evidence is available on high-risk disease with some concerns that RS-RARP may confer an increased positive margin rate based on pT3 results. In addition, RS-RARP may be more technically challenging in various scenarios such as anterior tumours, post-TURP, a grossly enlarged gland, or a bulky median lobe [37].

Figure 3. While the posterior wall of the anastomosis is being made, the silk suture is held continuously by the ProGrasp forceps under the same gentle traction, sufficient to present the urethra.

- Pelvic lymph node dissection

A systematic review demonstrated that performing pelvic lymph node dissection (PLND) during RP failed to improve oncological outcomes, including survival [38]. Moreover, two RCTs have failed to show a benefit of an extended approach vs. a limited PLND on early oncologic outcomes [39,40]. However, it is generally accepted that eLND provides important information for staging and prognosis which cannot be matched by any other currently available procedure [38].

Extended LND includes removal of the nodes overlying the external iliac artery and vein, the nodes within the obturator fossa located cranially and caudally to the obturator nerve, and the nodes medial and lateral to the internal iliac artery. With this template, 94% of patients are correctly staged [41].

The individual risk of patients harbouring positive LNs can be estimated based on validated nomograms. The Briganti nomogram [42,43], the Roach formula [44] or the Partin and MSKCC nomograms [45] have shown similar diagnostic accuracy in predicting LN invasion. These nomograms have all been developed in the pre-MRI setting based on systematic random biopsy. A risk of nodal metastases over 5% can be used to identify candidates for nodal sampling by eLND during RP [46–48].

- Sentinel node biopsy analysis

The rationale for a sentinel node biopsy (SNB) is based on the concept that a sentinel node is the first to be involved by migrating tumour cells. Therefore, when this node is negative it is possible to avoid an ePLND. There is heterogeneity and variation in techniques in relation to SNB (e.g. the optimal tracer) but a multidisciplinary collaborative endeavour attempted to standardise definitions, thresholds and strategies in relation to techniques of SNB using consensus methods [49].

- Prostatic anterior fat pad dissection and histologic analysis

Several multi-centre and large single-centre series have shown the presence of lymphoid tissue within the fat pad anterior to the endopelvic fascia; the prostatic anterior fat pad (PAFP) [50–56]. This lymphoid tissue is present in 5.5–10.6% of cases and contains metastatic PCa in up to 1.3% of intermediate- and high-risk patients.

- Management of the dorsal venous complex

Since the description of the anatomical open RP by Walsh and Donker in the 1980s, various methods of controlling bleeding from the dorsal venous complex (DVC) have been proposed to optimise visualisation [25]. In the open setting, blood loss and transfusion rates have been found to be significantly reduced when ligating the DVC prior to transection [57]. However, concerns have been raised regarding the effect of prior DVC ligation on apical margin positivity and continence recovery due to the proximity of the DVC to both the prostatic apex and the urethral sphincter muscle fibres. In the robotic-assisted laparoscopic technique, due to the increased pressure of pneumoperitoneum, whether prior DVC ligation was used or not, blood loss was not found to be significantly different in one study [58]. In another study, mean blood loss was significantly less with prior DVC ligation (184 vs. 176 mL, p = 0.033), however it is debatable whether this was clinically significant [59]. The positive apical margin rate was not different, however, the latter study showed earlier return to full continence at 5 months post-operatively in the no prior DVC ligation group (61% vs. 40%, p < 0.01).

Ligation of the DVC can be performed with standard suture or using a vascular stapler. One study found significantly reduced blood loss (494 mL vs. 288 mL) and improved apical margin status (13% vs. 2%) when using the stapler [60].

- Nerve-sparing surgery

During prostatectomy, preservation of the neurovascular bundles with parasympathetic nerve branches of the pelvic plexus may spare erectile function [61,62].

Although age and pre-operative function may remain the most important predictors for postoperative erectile function, nerve-sparing has also been associated with improved continence outcomes and may therefore still be relevant for men with poor erectile function [63,64]. The association with continence may be mainly due to the dissection technique used during nerve-sparing surgery, and not due to the preservation of the nerve bundles themselves [63].

Extra-, inter-, and intra-fascial dissection planes can be planned, with those closer to the prostate and performed bilaterally associated with superior (early) functional outcomes [65–68]. Furthermore, many different techniques are propagated such as retrograde approach after anterior release (vs. antegrade), and athermal and traction-free handling of bundles [69–71]. Nerve-sparing does not compromise cancer control if patients are carefully selected depending on tumour location, size and grade [72–74].

- Removal of seminal vesicles

The more aggressive forms of PCa may spread directly into the seminal vesicles (SVs). For oncological clearance, the SVs have traditionally been removed intact with the prostate specimen [75]. However, in some patients the tips of the SVs can be challenging to dissect free. Furthermore, the cavernous nerves run past the SV tips such that indiscriminate dissection of the SV tips could potentially lead to ED [76].

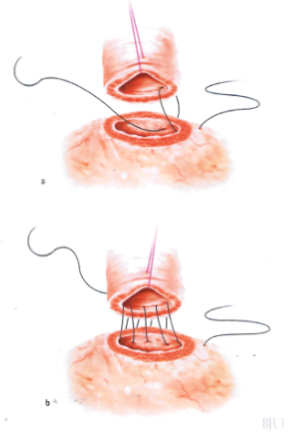

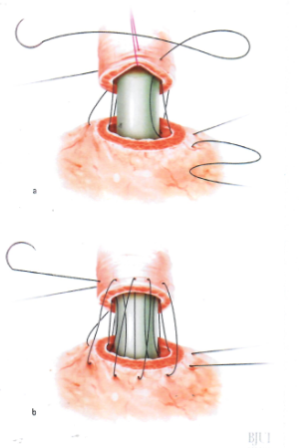

- Techniques of vesico-urethral anastomosis

Following prostate removal, the bladder neck is anastomosed to the membranous urethra. The objective is to create a precisely aligned, watertight, tension-free, and stricture-free anastomosis that preserves the integrity of the intrinsic sphincter mechanism. Several methods have been described, based on the direct or indirect approach, the type of suture (i.e. barbed vs. non-barbed/monofilament), and variation in suturing technique (e.g., continuous vs. interrupted, or single-needle vs. double-needle running suture). The direct vesico-urethral anastomosis, which involves the construction of a primary end-to-end inter-mucosal anastomosis of the bladder neck to the membranous urethra by using 6 interrupted sutures placed circumferentially, has become the standard method of reconstruction for open RP [77].

The development of laparoscopic- and robotic-assisted techniques to perform RP have facilitated the introduction of new suturing techniques for the anastomosis. A systematic review and meta-analysis compared unidirectional barbed suture vs. conventional non-barbed suture for vesico-urethral anastomosis during robotic-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy (RALP) [78].

Figure 4: Preparation of the urethra, bladder neck and the posterior suture

Although the review found slight advantages for continuous suturing over interrupted suturing in terms of catheterisation time, anastomosis time and rate of extravasation, the overall quality of evidence was low and no clear recommendations were possible. A recent RCT [79] compared the technique of suturing using a single absorbable running suture vs. a double-needle single-knot running suture (i.e. Van Velthoven technique) in laparoscopic RP [80]. The study found slightly reduced anastomosis time with the single running suture technique, but anastomotic leak, stricture, and continence rates were similar.

Figure 5: Placing the catheter and the anterior suture

Bladder neck management:

- Bladder neck mucosal eversion

Some surgeons perform mucosal eversion of the bladder neck as its own step in open RP with the aim of securing a mucosa-to-mucosa vesico-urethral anastomosis and avoiding anastomotic stricture.

An alternative is to simply ensure bladder mucosa is included in the full thickness anastomotic sutures.

- Bladder neck preservation

Whilst the majority of urinary continence is maintained by the external urethral sphincter at the membranous urethra (see below), a minor component is contributed by the internal lissosphincter at the bladder neck [81].

Preservation of the bladder neck has therefore been proposed to improve continence recovery post-RP. A RCT assessing continence recovery at 12 months and 4 years showed improved objective and subjective urinary continence in both the short- and long term without any adverse effect on oncological outcome [82].

Figure 6: Parachute the bladder neck down onto the urethra

- Urethral length preservation

The membranous urethra sits immediately distal to the prostatic apex and is chiefly responsible, along with its surrounding pelvic floor support structures, for urinary continence. It consists of the external rhabdosphincter which surrounds an inner layer of smooth muscle.

Therefore, it is likely that preservation of as much urethral length as possible during RP will maximise the chance of early return to continence. It may also be useful to measure urethral length pre-operatively to facilitate counselling of patients on their relative likelihood of early post-operative continence.

- Cystography prior to catheter removal

Cystography may be used prior to catheter removal to check for a substantial anastomotic leak. If such a leak is found, catheter removal may then be deferred to allow further healing and sealing of the anastomosis.

- Urinary catheter

A urinary catheter is routinely placed during RP to enable bladder rest and drainage of urine while the vesicourethral anastomosis heals. Compared to a traditional catheter duration of around 1 week, some centres remove the transurethral catheter early (post-operative day 2–3), usually after thorough anastomosis with posterior reconstruction or in patients selected peri-operatively on the basis of anastomosis quality [83–86].

- Use of a pelvic drain

A pelvic drain has traditionally been used in RP for potential drainage of urine leaking from the vesico-urethral anastomosis, blood, or lymphatic fluid when a PLND has been performed.

When the anastomosis is found to be watertight intra-operatively, it is reasonable to avoid inserting a pelvic drain. There is no evidence to guide usage of a pelvic drain in PLND.

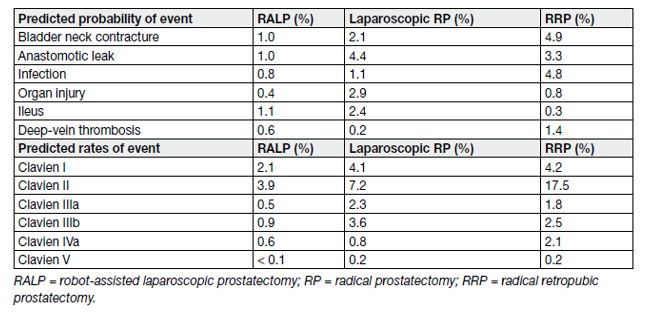

- Acute and chronic complications of surgery

Post-operative incontinence and ED are common problems following surgery for PCa. A key consideration is whether these problems are reduced by using newer techniques such as RALP. Systematic reviews have documented complication rates after RALP [30,87–90], and can be compared with contemporaneous reports after radical RRP [91]. A prospective controlled non-RCT of patients undergoing RP in 14 centres using RALP or RRP showed that 12 months after RALP, 21.3% of patients were incontinent, as were 20.2% after RRP (adjusted OR: 1.08, 95% CI: 0.87–1.34) [92]. Erectile dysfunction was observed in 70.4% after RALP and 74.7% after RRP. The adjusted OR was 0.81 (95% CI: 0.66–0.98) [92].

A systematic review and meta-analysis of unplanned hospital visits and re-admissions post-RP analysed 60 studies with over 400,000 patients over a 20-year period up to 2020. It found an emergency room visit rate of 12% and a hospital re-admission rate of 4% at 30 days post-operatively [93].

The intra-and peri-operative complications of retropubic RP and RALP are listed in Table 5.

Table 5. Intra-and peri-operative complications of retropublic RP and RALP

The early use of phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE5) inhibitors in penile rehabilitation remains controversial resulting in a lack of clear recommendations.

- Effect of anterior and posterior reconstruction on continence

Preservation of integrity of the external urethral sphincter is critical for continence post-RP. Less clear is the effect of reconstruction of surrounding support structures to return to continence.

In addition, techniques used to perform both anterior suspension or reconstruction and posterior reconstruction are varied. For example, anterior suspension is performed either through periosteum of the pubis or the combination of ligated DVC and puboprostatic ligaments (PPL). Posterior reconstruction from rhabdosphincter is described to either Denonvilliers fascia posterior to bladder or to posterior bladder wall itself.

As there is conflicting evidence on the effect of anterior and/or posterior reconstruction on return to continence post-RP, no recommendations can be made. However, no studies showed an increase in adverse oncologic outcome or complications with reconstruction.

- Deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis

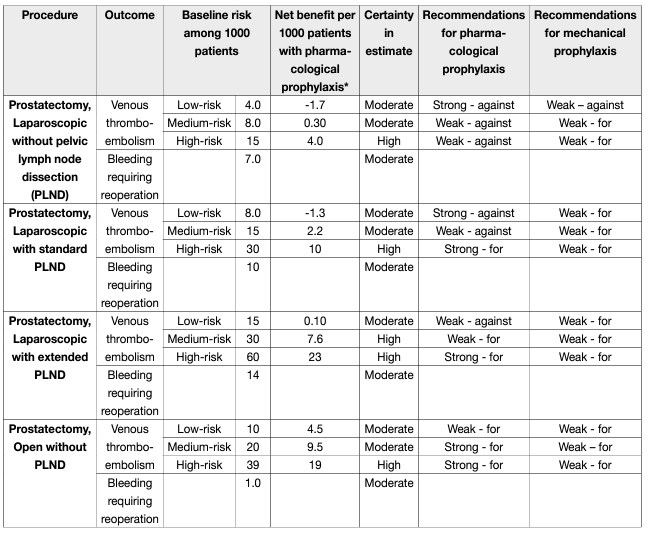

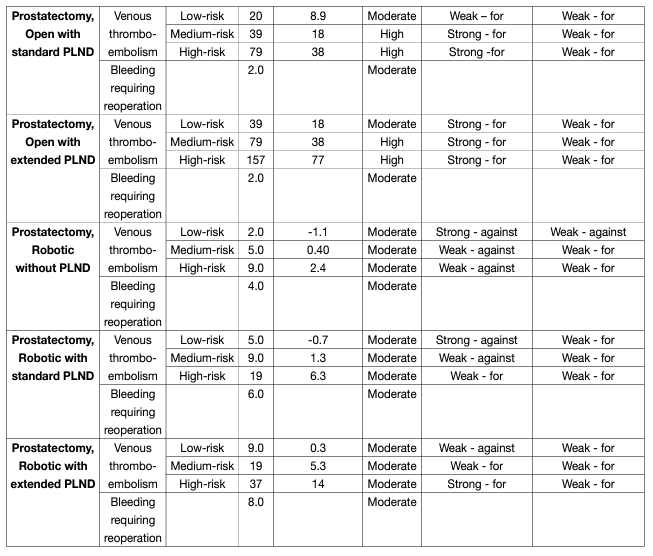

EAU Guidelines recommendations on post-RP deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis (see table 6).

Table 6: Procedure-specific evidence summaries with recommendations for radical prostatectomies

For patients undergoing robotic radical prostatectomy without PLND, for those at low risk of VTE, the Panel recommends against use of pharmacologic prophylaxis (strong, moderate-quality evidence) and suggests against use of mechanical prophylaxis (weak, low-quality evidence); for those at medium and high risk, the Panel suggests against use of pharmacologic prophylaxis (weak, moderate-quality evidence) and suggests use of mechanical prophylaxis until ambulation (weak, low-quality evidence).

For patients undergoing robotic radical prostatectomy with standard PLND, for those at low risk of VTE, the Panel recommends against use of pharmacologic prophylaxis (strong, moderate-quality evidence); for those at medium risk, the Panel suggests against use of pharmacologic prophylaxis (weak, moderate-quality evidence); for those at high risk, the Panel suggests use of pharmacologic prophylaxis (weak, moderatequality evidence); and for all patients, the Panel suggests use of mechanical prophylaxis until ambulation (weak, low-quality evidence).

For patients undergoing robotic radical prostatectomy with extended PLND, for those at low risk of VTE, the Panel suggests against use of pharmacologic prophylaxis (weak, moderate-quality evidence); for those at medium risk, the Panel suggests use of pharmacologic prophylaxis (weak, moderate-quality evidence); for those at high risk, the Panel recommends use of pharmacologic prophylaxis (strong, moderate-quality evidence); and for all patients, the Panel suggests use of mechanical prophylaxis until ambulation (weak, lowquality evidence).

However, these recommendations should be adapted based on national recommendations, when available.

- Early complications of extended lymph node dissection

Overall complication rates of 19.8% vs. 8.2% were noted for eLND vs. limited LND, respectively, with lymphoceles (10.3% vs. 4.6%) being the most common adverse event.

The third treatment modality with radiotherapy contain the intensity-modulated RT (IMRT) or volumetric arc radiation therapy (VMAT) with image-guided RT (IGRT) is currently widely recognised as the best available approach for External beam radiation therapy (EBRT).

- External beam radiation therapy

Intensity-modulated )EBRT( and volumetric arc external-beam RT (VMAT) employ dynamic multileaf collimators, which automatically and continuously adapt to the contours of the target volume seen by each beam.

A meta-analysis by Yu et al., (23 studies, 9,556 patients) concluded that IMRT significantly decreases the occurrence of grade 2–4 acute GI toxicity, late GI toxicity and late rectal bleeding, and achieves better PSA relapse-free survival in comparison with 3D-CRT.

The advantage of VMAT over IMRT is shorter treatment times, generally two to three minutes. Both techniques allow for a more complex distribution of the dose to be delivered and provide concave isodose curves, which are particularly useful as a means of sparing the rectum.

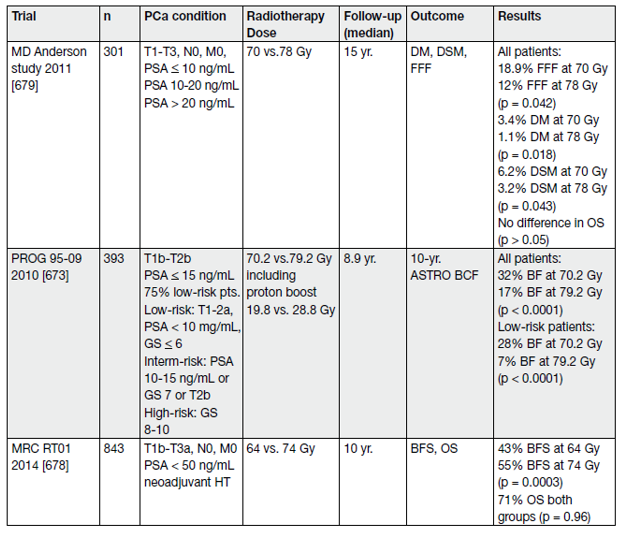

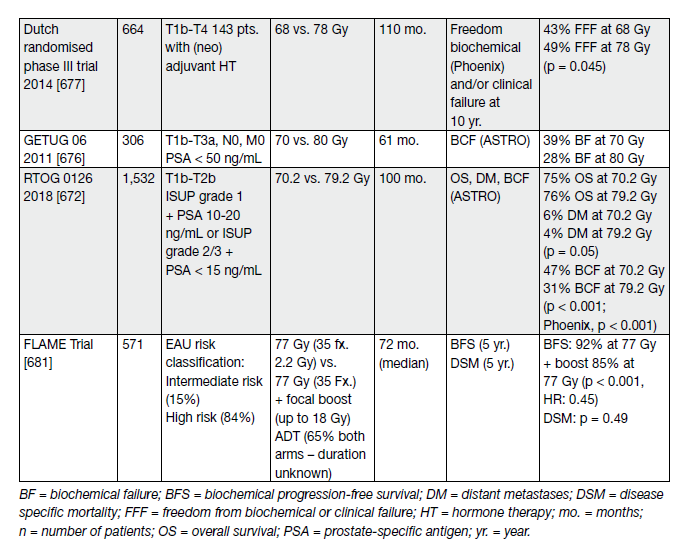

- Dose escalation

Local control is a critical issue for the outcome of RT of PCa. It has been shown that local failure due to insufficient total dose is prognostic for death from PCa as a second wave of metastases is seen 5 to 10 years later on [94]. Several RCTs have shown that dose escalation (range 74–80 Gy) has a significant impact on 10-year biochemical relapse as well as metastases and disease-specific mortality [95–102]. These trials have generally included patients from several risk groups, and the use of neoadjuvant/adjuvant HT has varied (see Table 7).

Table 7. Randomised trials of dose escalation in localised PCa

- Hypofractionation

Fractionated RT utilises differences in the DNA repair capacity of normal and tumour tissue and slowly proliferating cells are very sensitive to an increased dose per fraction [103]. A meta-analysis of 25 studies including > 14,000 patients concluded that since PCa has a slow proliferation rate, hypofractionated RT could be more effective than conventional fractions of 1.8–2 Gy [104]. Hypofractionation (HFX) has the added advantage of being more convenient for the patient at lower cost.

Moderate HFX is defined as RT with 2.5–3.4 Gy/fx. Several studies report on moderate HFX applied in various techniques also including HT in part [105–115].

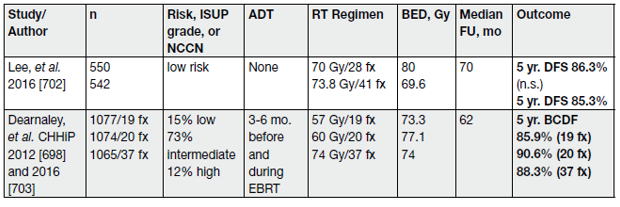

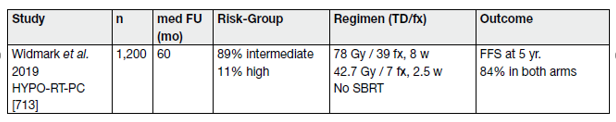

Moderate HFX should only be done by experienced teams using high-quality EBRT using IGRT and IMRT/ VMAT and published phase III protocols should be adhered to (Table 8).

Table 8. Major phase III randomized trials of moderate hypofractionation for primary treatment

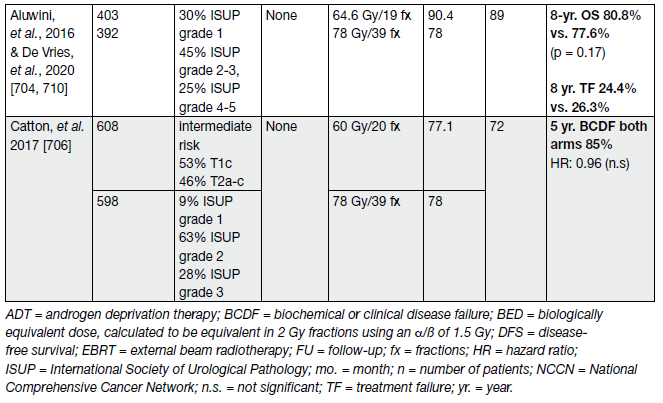

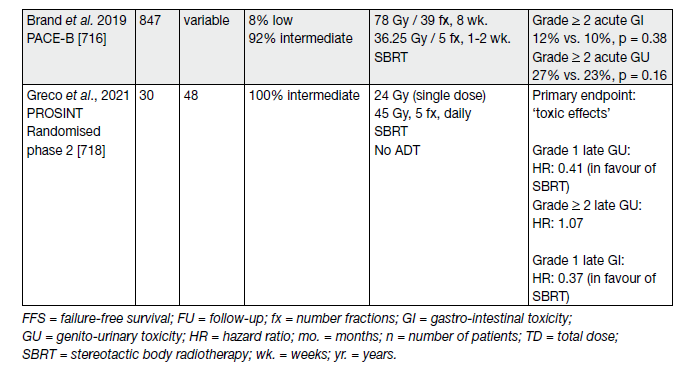

Ultra-HFX has been defined as RT with > 3.4 Gy per fraction [115]. It requires IGRT and stereotactic body RT (SBRT).

Table 9 provides an overview of selected studies.

First results of a small (n = 30) randomised phase-II trial in intermediate-risk PCa of ‘ultra-high single dose RT’ (SDRT) with 24 Gy compared with an extreme hypofractionated stereotactic body RT regime with 5×9 Gy to the prostate, have been published recently (see Table 9) [116].

Table 9. Selected trials on ultra-hypofractionation for intact lacalised PCa

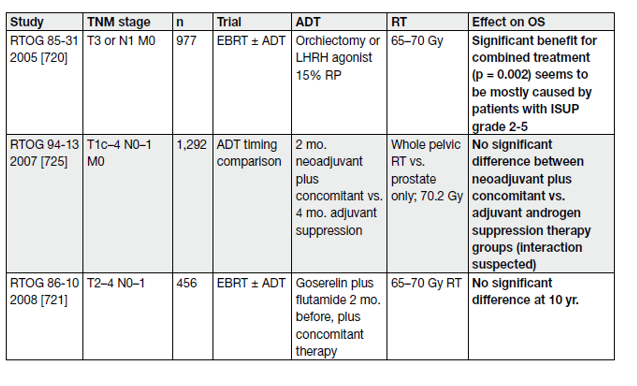

- Neoadjuvant or adjuvant hormone therapy plus radiotherapy

The combination of RT with LHRH ADT has definitively proven its superiority compared with RT alone followed by androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) on relapse, as shown by phase III RCTs [117–121] (Table 10).

Table 10. Selected studies of use and duration of ADT in combination with RT for PCa

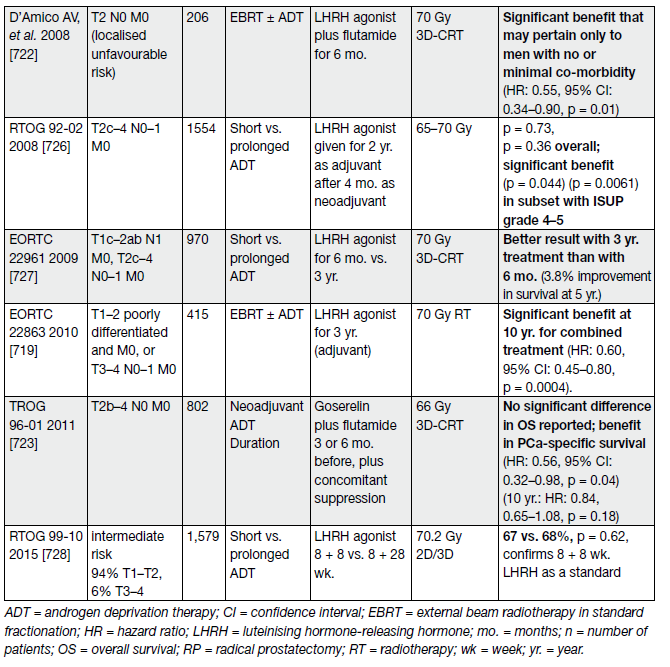

The question of the added value of EBRT combined with ADT has been clarified by 3 RCTs. All showed a clear benefit of adding EBRT to long-term ADT (see Table 11).

Table 11. Selected studies of ADT in combination with, or without, RT for PCa

- Proton beam therapy

In theory, proton beams are an attractive alternative to photon-beam RT for PCa, as they deposit almost all their radiation dose at the end of the particle’s path in tissue (the Bragg peak), in contrast to photons which deposit radiation along their path. There is also a very sharp fall-off for proton beams beyond their deposition depth, meaning that critical normal tissues beyond this depth could be effectively spared. In contrast, photon beams continue to deposit energy until they leave the body, including an exit dose.

A RCT comparing equivalent doses of proton-beam therapy with IMRT is underway. Meanwhile, proton therapy must be regarded as an experimental alternative to photon-beam therapy.

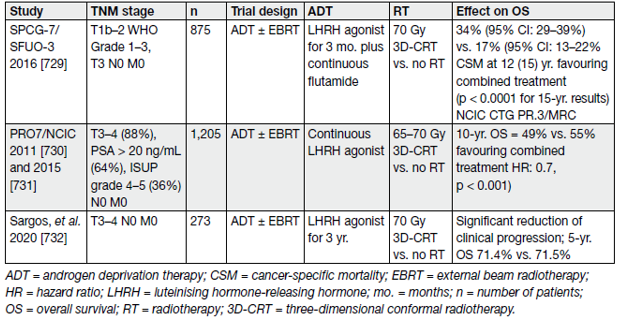

Brachytherapy:

- Low-dose rate brachytherapy

Low-dose rate (LDR) brachytherapy uses radioactive seeds permanently implanted into the prostate. There is a consensus on the group of patients with the best outcomes after LDR monotherapy [122] for low- or favourable intermediate-risk and good urinary function defined as an International Prostatic Symptom Score (IPSS) < 12 and maximum flow rate > 15 mL/min on urinary flow tests, as per NCCN definition [123]. In addition, with due attention to dose distribution, patients having had a previous TURP can undergo brachytherapy without an increase in risk of urinary toxicity.

- High-dose rate brachytherapy

High-dose rate (HDR) brachytherapy uses a radioactive source temporarily introduced into the prostate to deliver radiation. The technical differences are outlined in Table 12.

Table 12. Difference between LDR and HDR brachytherapy

- Acute side effects of external beam radiotherapy and brachytherapy

Gastro-intestinal and urinary side effects are common during and after EBRT. In the EORTC 22991 trial, approximately 50% of patients reported acute GU toxicity of grade 1, 20% of grade 2, and 2% grade 3. In the same trial, approximately 30% of patients reported acute grade 1 GI toxicity, 10% grade 2, and less than 1% grade 3. Common toxicities included dysuria, urinary frequency, urinary retention, haematuria, diarrhoea, rectal bleeding and proctitis [124].

REFERENCES:

1. Chodak, G.W., et al. Results of conservative management of clinically localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med, 1994. 330: 242. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8272085/

2. Sandblom, G., et al. Long-term survival in a Swedish population-based cohort of men with prostate cancer. Urology, 2000. 56: 442. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10962312/

3. Johansson, J.E., et al. Natural history of localised prostatic cancer. A population-based study in 223 untreated patients. Lancet, 1989. 1: 799. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2564901/

4. Bill-Axelson, A., et al. Radical prostatectomy versus watchful waiting in early prostate cancer. N Engl J Med, 2005. 352: 1977. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15888698/

5. Adolfsson, J., et al. The 20-Yr outcome in patients with well- or moderately differentiated clinically localized prostate cancer diagnosed in the pre-PSA era: the prognostic value of tumour ploidy and comorbidity. Eur Urol, 2007. 52: 1028. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17467883/

6. Jonsson, E., et al. Adenocarcinoma of the prostate in Iceland: a population-based study of stage, Gleason grade, treatment and long-term survival in males diagnosed between 1983 and 1987. Scand J Urol Nephrol, 2006. 40: 265. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16916765/

7. Lu-Yao, G.L., et al. Outcomes of localized prostate cancer following conservative management. Jama, 2009. 302: 1202. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19755699/

8. Hayes, J.H., et al. Observation versus initial treatment for men with localized, low-risk prostate cancer: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Ann Intern Med, 2013. 158: 853. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23778902/

9. Albertsen, P.C., et al. Impact of comorbidity on survival among men with localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol, 2011. 29: 1335. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21357791/

10. Albertsen, P.C. Observational studies and the natural history of screen-detected prostate cancer. Curr Opin Urol, 2015. 25: 232. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25692723/

11. Bruinsma, S.M., et al. Expert consensus document: Semantics in active surveillance for men with localized prostate cancer – results of a modified Delphi consensus procedure. Nat Rev Urol, 2017. 14: 312. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28290462/

12. Thomsen, F.B., et al. Active surveillance for clinically localized prostate cancer–a systematic review. J Surg Oncol, 2014. 109: 830. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24610744/

13. Tosoian, J.J., et al. Intermediate and Longer-Term Outcomes From a Prospective Active-Surveillance Program for Favorable-Risk Prostate Cancer. J Clin Oncol, 2015. 33: 3379. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26324359/

14. Bill-Axelson, A., et al. Radical Prostatectomy or Watchful Waiting in Prostate Cancer – 29-Year Follow-up. N Engl J Med, 2018. 379: 2319. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30575473/

15. Adolfsson, J. Watchful waiting and active surveillance: the current position. BJU Int, 2008. 102: 10. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18422774/

16. Hatzinger, M., et al. [The history of prostate cancer from the beginning to DaVinci]. Aktuelle Urol, 2012. 43: 228. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23035261/

17. Kretschmer, A., et al. Perioperative patient education improves long-term satisfaction rates of lowrisk prostate cancer patients after radical prostatectomy. World J Urol, 2017. 35: 1205. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28093628/

18. Gyomber, D., et al. Improving informed consent for patients undergoing radical prostatectomy using multimedia techniques: a prospective randomized crossover study. BJU Int, 2010. 106: 1152. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20346048/

19. Huber, J., et al. Multimedia support for improving preoperative patient education: a randomized controlled trial using the example of radical prostatectomy. Ann Surg Oncol, 2013. 20: 15. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22851045/

20. Wake, N., et al. Patient-specific 3D printed and augmented reality kidney and prostate cancer models: impact on patient education. 3D Print Med, 2019. 5: 4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30783869/

21. De Nunzio, C., et al. The EORTC quality of life questionnaire predicts early and long-term incontinence in patients treated with robotic assisted radical prostatectomy: Analysis of a large single center cohort. Urol Oncol, 2019. 37: 1006. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31326315/

22. Chang, J.I., et al. Preoperative Pelvic Floor Muscle Exercise and Postprostatectomy Incontinence: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Eur Urol, 2016. 69: 460. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26610857/

23. Bonkat, G., et al. EAU Guidelines on Urological Infections. Edn. presented at the 37th EAU Annual Congress Amsterdam 2022. EAU Guidelines Office, Arnhem, The Netherlands. https://uroweb.org/guideline/urological-infections/

24. Kumar, S., et al. Neo-adjuvant and adjuvant hormone therapy for localised and locally advanced prostate cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2006: CD006019. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17054269/

25. Walsh, P.C., et al. Impotence following radical prostatectomy: insight into etiology and prevention. J Urol, 1982. 128: 492. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7120554/

26. Schuessler, W.W., et al. Laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: initial short-term experience. Urology, 1997. 50: 854. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9426713/

27. Binder, J., et al. [Robot-assisted laparoscopy in urology. Radical prostatectomy and reconstructive retroperitoneal interventions]. Urologe A, 2002. 41: 144. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11993092/

28. Yaxley, J.W., et al. Robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy versus open radical retropubic prostatectomy: early outcomes from a randomised controlled phase 3 study. Lancet, 2016. 388: 1057. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27474375/

29. Coughlin, G.D., et al. Robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy versus open radical retropubic prostatectomy: 24-month outcomes from a randomised controlled study. Lancet Oncol, 2018. 19: 1051. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30017351/

30. Ramsay, C., et al. Systematic review and economic modelling of the relative clinical benefit and cost-effectiveness of laparoscopic surgery and robotic surgery for removal of the prostate in men with localised prostate cancer. Health Technol Assess, 2012. 16: 1. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23127367/

31. Galfano, A., et al. A new anatomic approach for robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy: a feasibility study for completely intrafascial surgery. Eur Urol, 2010. 58: 457. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20566236/

32. Checcucci, E., et al. Retzius-sparing robot-assisted radical prostatectomy vs the standard approach: a systematic review and analysis of comparative outcomes. BJU Int, 2020. 125: 8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31373142/

33. Phukan, C., et al. Retzius sparing robotic assisted radical prostatectomy vs. conventional robotic assisted radical prostatectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Urol, 2020. 38: 1123. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31089802/

34. Tai, T.E., et al. Effects of Retzius sparing on robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Surg Endosc, 2020. 34: 4020. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31617093/

35. Rosenberg, J.E., et al. Retzius-sparing versus standard robotic-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy for the treatment of clinically localized prostate cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2020. 8: CD013641. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32813279/

36. Lee, J., et al. Retzius Sparing Robot-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy Conveys Early Regain of Continence over Conventional Robot-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy: A Propensity Score Matched Analysis of 1,863 Patients. J Urol, 2020. 203: 137. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31347951/

37. Stonier, T., et al. Retzius-sparing robot-assisted radical prostatectomy (RS-RARP) vs standard RARP: it’s time for critical appraisal. BJU Int, 2019. 123: 5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29959814/

38. Fossati, N., et al. The Benefits and Harms of Different Extents of Lymph Node Dissection During Radical Prostatectomy for Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review. Eur Urol, 2017. 72: 84. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28126351/

39. Lestingi, J.F.P., et al. Extended Versus Limited Pelvic Lymph Node Dissection During Radical Prostatectomy for Intermediate- and High-risk Prostate Cancer: Early Oncological Outcomes from a Randomized Phase 3 Trial. Eur Urol, 2021. 79: 595. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33293077/

40. Touijer, K.A., et al. Limited versus Extended Pelvic Lymph Node Dissection for Prostate Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Eur Urol Oncol, 2021. 4: 532. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33865797/

41. Mattei, A., et al. The template of the primary lymphatic landing sites of the prostate should be revisited: results of a multimodality mapping study. Eur Urol, 2008. 53: 118. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17709171/

42. Briganti, A., et al. Updated nomogram predicting lymph node invasion in patients with prostate cancer undergoing extended pelvic lymph node dissection: the essential importance of percentage of positive cores. Eur Urol, 2012. 61: 480. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22078338/

43. Gandaglia, G., et al. Development and Internal Validation of a Novel Model to Identify the Candidates for Extended Pelvic Lymph Node Dissection in Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol, 2017. 72: 632. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28412062/

44. Roach, M., 3rd, et al. Predicting the risk of lymph node involvement using the pre-treatment prostate specific antigen and Gleason score in men with clinically localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 1994. 28: 33. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7505775/

45. Cimino, S., et al. Comparison between Briganti, Partin and MSKCC tools in predicting positive lymph nodes in prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Scand J Urol, 2017. 51: 345. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28644701/

46. Abdollah, F., et al. Indications for pelvic nodal treatment in prostate cancer should change. Validation of the Roach formula in a large extended nodal dissection series. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2012. 83: 624. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22099031/

47. Dell’Oglio, P., et al. External validation of the European association of urology recommendations for pelvic lymph node dissection in patients treated with robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. J Endourol, 2014. 28: 416. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24188052/

48. Hinev, A.I., et al. Validation of nomograms predicting lymph node involvement in patients with prostate cancer undergoing extended pelvic lymph node dissection. Urol Int, 2014. 92: 300. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24480972/

49. van der Poel, H.G., et al. Sentinel node biopsy for prostate cancer: report from a consensus panel meeting. BJU Int, 2017. 120: 204. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28188689/

50. Weng, W.C., et al. Impact of prostatic anterior fat pads with lymph node staging in prostate cancer. J Cancer, 2018. 9: 3361. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30271497/

51. Hosny, M., et al. Can Anterior Prostatic Fat Harbor Prostate Cancer Metastasis? A Prospective Cohort Study. Curr Urol, 2017. 10: 182. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29234260/

52. Ball, M.W., et al. Pathological analysis of the prostatic anterior fat pad at radical prostatectomy: insights from a prospective series. BJU Int, 2017. 119: 444.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27611825/

53. Kwon, Y.S., et al. Oncologic outcomes in men with metastasis to the prostatic anterior fat pad lymph nodes: a multi-institution international study. BMC Urol, 2015. 15: 79. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26231860/

54. Ozkan, B., et al. Role of anterior prostatic fat pad dissection for extended lymphadenectomy in prostate cancer: a non-randomized study of 100 patients. Int Urol Nephrol, 2015. 47: 959. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25899767/

55. Kim, I.Y., et al. Detailed analysis of patients with metastasis to the prostatic anterior fat pad lymph nodes: a multi-institutional study. J Urol, 2013. 190: 527. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23485503/

56. Hansen, J., et al. Assessment of rates of lymph nodes and lymph node metastases in periprostatic fat pads in a consecutive cohort treated with retropubic radical prostatectomy. Urology, 2012. 80: 877. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22950996/

57. Rainwater, L.M., et al. Technical consideration in radical retropubic prostatectomy: blood loss after ligation of dorsal venous complex. J Urol, 1990. 143: 1163. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2342176/

58. Woldu, S.L., et al. Outcomes with delayed dorsal vein complex ligation during robotic assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy. Can J Urol, 2013. 20: 7079. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24331354/

59. Lei, Y., et al. Athermal division and selective suture ligation of the dorsal vein complex during robotassisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: description of technique and outcomes. Eur Urol, 2011. 59: 235. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20863611/

60. Wu, S.D., et al. Suture versus staple ligation of the dorsal venous complex during robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. BJU Int, 2010. 106: 385. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20067457/

61. Walsh, P.C., et al. Radical prostatectomy and cystoprostatectomy with preservation of potency. Results using a new nerve-sparing technique. Br J Urol, 1984. 56: 694. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6534493/

62. Walz, J., et al. A Critical Analysis of the Current Knowledge of Surgical Anatomy of the Prostate Related to Optimisation of Cancer Control and Preservation of Continence and Erection in Candidates for Radical Prostatectomy: An Update. Eur Urol, 2016. 70: 301. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26850969/

63. Michl, U., et al. Nerve-sparing Surgery Technique, Not the Preservation of the Neurovascular Bundles, Leads to Improved Long-term Continence Rates After Radical Prostatectomy. Eur Urol, 2016. 69: 584. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26277303/

64. Avulova, S., et al. The Effect of Nerve Sparing Status on Sexual and Urinary Function: 3-Year Results from the CEASAR Study. J Urol, 2018. 199: 1202. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29253578/

65. Stolzenburg, J.U., et al. A comparison of outcomes for interfascial and intrafascial nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy. Urology, 2010. 76: 743. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20573384/

66. Steineck, G., et al. Degree of preservation of the neurovascular bundles during radical prostatectomy and urinary continence 1 year after surgery. Eur Urol, 2015. 67: 559. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25457018/

67. Shikanov, S., et al. Extrafascial versus interfascial nerve-sparing technique for robotic-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy: comparison of functional outcomes and positive surgical marginscharacteristics. Urology, 2009. 74: 611. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19616830/

68. Tewari, A.K., et al. Anatomical grades of nerve sparing: a risk-stratified approach to neuralhammock sparing during robot-assisted radical prostatectomy (RARP). BJU Int, 2011. 108: 984. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21917101/

69. Nielsen, M.E., et al. High anterior release of the levator fascia improves sexual function following open radical retropubic prostatectomy. J Urol, 2008. 180: 2557. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18930504/

70. Ko, Y.H., et al. Retrograde versus antegrade nerve sparing during robot-assisted radical prostatectomy: which is better for achieving early functional recovery? Eur Urol, 2013. 63: 169. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23092543/

71. Tewari, A.K., et al. Functional outcomes following robotic prostatectomy using athermal, traction free risk-stratified grades of nerve sparing. World J Urol, 2013. 31: 471. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23354288/

72. Catalona, W.J., et al. Nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy: evaluation of results after 250 patients. J Urol, 1990. 143: 538. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2304166/

73. Neill, M.G., et al. Does intrafascial dissection during nerve-sparing laparoscopic radical prostatectomy compromise cancer control? BJU Int, 2009. 104: 1730. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20063449/

74. Ward, J.F., et al. The impact of surgical approach (nerve bundle preservation versus wide local excision) on surgical margins and biochemical recurrence following radical prostatectomy. J Urol, 2004. 172: 1328. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15371834/

75. Beulens, A.J.W., et al. Linking surgical skills to postoperative outcomes: a Delphi study on the robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. J Robot Surg, 2019. 13: 675. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30610535/

76. Gilbert, S.M., et al. Functional Outcomes Following Nerve Sparing Prostatectomy Augmented with Seminal Vesicle Sparing Compared to Standard Nerve Sparing Prostatectomy: Results from a Randomized Controlled Trial. J Urol, 2017. 198: 600. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28392393/

77. Steiner, M.S., et al. Impact of anatomical radical prostatectomy on urinary continence. J Urol, 1991. 145: 512. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1997701/

78. Li, H., et al. The Use of Unidirectional Barbed Suture for Urethrovesical Anastomosis during Robot- Assisted Radical Prostatectomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Efficacy and Safety. PLoS One, 2015. 10: e0131167. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26135310/

79. Wiatr, T., et al. Single Running Suture versus Single-Knot Running Suture for Vesicourethral Anastomosis in Laparoscopic Radical Prostatectomy: A Prospective Randomised Comparative Study. Urol Int, 2015. 95: 445. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26655169/

80. Van Velthoven, R.F., et al. Technique for laparoscopic running urethrovesical anastomosis:the single knot method. Urology, 2003. 61: 699. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12670546/

81. Bellangino, M., et al. Systematic Review of Studies Reporting Positive Surgical Margins After Bladder Neck Sparing Radical Prostatectomy. Curr Urol Rep, 2017. 18: 99. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29116405/

82. Nyarangi-Dix, J.N., et al. Complete bladder neck preservation promotes long-term postprostatectomy continence without compromising midterm oncological outcome: analysis of a randomised controlled cohort. World J Urol, 2018. 36: 349. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29214353/

83. Gratzke, C., et al. Early Catheter Removal after Robot-assisted Radical Prostatectomy: Surgical Technique and Outcomes for the Aalst Technique (ECaRemA Study). Eur Urol, 2016. 69: 917. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26578444/

84. James, P., et al. Safe removal of the urethral catheter 2 days following laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. ISRN Oncol, 2012. 2012: 912642. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22957273/

85. Lista, G., et al. Early Catheter Removal After Robot-assisted Radical Prostatectomy: Results from a Prospective Single-institutional Randomized Trial (Ripreca Study). Eur Urol Focus, 2020. 6: 259. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30413390/

86. Brassetti, A., et al. Removing the urinary catheter on post-operative day 2 after robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: a feasibility study from a single high-volume referral centre. J Robot Surg, 2018. 12: 467. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29177945/

87. Novara, G., et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of studies reporting oncologic outcome after robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol, 2012. 62: 382. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22749851/

88. Novara, G., et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of perioperative outcomes and complications after robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol, 2012. 62: 431. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22749853/

89. Ficarra, V., et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of studies reporting potency rates after robotassisted radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol, 2012. 62: 418. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22749850/

90. Ficarra, V., et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of studies reporting urinary continence recovery after robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol, 2012. 62: 405. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22749852/

91. Maffezzini, M., et al. Evaluation of complications and results in a contemporary series of 300 consecutive radical retropubic prostatectomies with the anatomic approach at a single institution. Urology, 2003. 61: 982. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12736020/

92. Haglind, E., et al. Urinary Incontinence and Erectile Dysfunction After Robotic Versus Open Radical Prostatectomy: A Prospective, Controlled, Nonrandomised Trial. Eur Urol, 2015. 68: 216. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25770484/

93. Mukkala, A.N., et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of unplanned hospital visits and re-admissions following radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. Can Urol Assoc J, 2021. 15: E531. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33750517/

94. Kishan, A.U., et al. Local Failure and Survival After Definitive Radiotherapy for Aggressive Prostate Cancer: An Individual Patient-level Meta-analysis of Six Randomized Trials. Eur Urol, 2020. 77: 201. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31718822/

95. Michalski, J.M., et al. Effect of Standard vs Dose-Escalated Radiation Therapy for Patients With Intermediate-Risk Prostate Cancer: The NRG Oncology RTOG 0126 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol, 2018. 4: e180039. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29543933/

96. Zietman, A.L., et al. Randomized trial comparing conventional-dose with high-dose conformal radiation therapy in early-stage adenocarcinoma of the prostate: long-term results from proton radiation oncology group/american college of radiology 95-09. J Clin Oncol, 2010. 28: 1106. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20124169/

97. Viani, G.A., et al. Higher-than-conventional radiation doses in localized prostate cancer treatment: a meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2009. 74: 1405. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19616743/

98. Peeters, S.T., et al. Dose-response in radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer: results of the Dutch multicenter randomized phase III trial comparing 68 Gy of radiotherapy with 78 Gy. J Clin Oncol, 2006. 24: 1990. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16648499/

99. Beckendorf, V., et al. 70 Gy versus 80 Gy in localized prostate cancer: 5-year results of GETUG 06 randomized trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2011. 80: 1056. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21147514/

100. Heemsbergen, W.D., et al. Long-term results of the Dutch randomized prostate cancer trial: impact of dose-escalation on local, biochemical, clinical failure, and survival. Radiother Oncol, 2014. 110: 104. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24246414/

101. Dearnaley, D.P., et al. Escalated-dose versus control-dose conformal radiotherapy for prostate cancer: long-term results from the MRC RT01 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol, 2014. 15: 464. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24581940/

102. Pasalic, D., et al. Dose Escalation for Prostate Adenocarcinoma: A Long-Term Update on the Outcomes of a Phase 3, Single Institution Randomized Clinical Trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2019. 104: 790. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30836166/

103. Fowler, J.F. The radiobiology of prostate cancer including new aspects of fractionated radiotherapy. Acta Oncol, 2005. 44: 265. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16076699/

104. Dasu, A., et al. Prostate alpha/beta revisited — an analysis of clinical results from 14 168 patients. Acta Oncol, 2012. 51: 963. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22966812/

105. Dearnaley, D., et al. Conventional versus hypofractionated high-dose intensity-modulated radiotherapy for prostate cancer: preliminary safety results from the CHHiP randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol, 2012. 13: 43. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22169269/

106. Kuban, D.A., et al. Preliminary Report of a Randomized Dose Escalation Trial for Prostate Cancer using Hypofractionation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2010. 78: S58. https://www.redjournal.org/article/S0360-3016(10)01144-2/fulltext

107. Pollack, A., et al. Randomized trial of hypofractionated external-beam radiotherapy for prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol, 2013. 31: 3860. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24101042/

108. Aluwini, S., et al. Hypofractionated versus conventionally fractionated radiotherapy for patients with prostate cancer (HYPRO): acute toxicity results from a randomised non-inferiority phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol, 2015. 16: 274. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25656287/

109. Lee, W.R., et al. Randomized Phase III Noninferiority Study Comparing Two Radiotherapy Fractionation Schedules in Patients With Low-Risk Prostate Cancer. J Clin Oncol, 2016. 34: 2325. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27044935/

110. Dearnaley, D., et al. Conventional versus hypofractionated high-dose intensity-modulated radiotherapy for prostate cancer: 5-year outcomes of the randomised, non-inferiority, phase 3 CHHiP trial. Lancet Oncol, 2016. 17: 1047. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27339115/

111. Aluwini, S., et al. Hypofractionated versus conventionally fractionated radiotherapy for patients with prostate cancer (HYPRO): late toxicity results from a randomised, non-inferiority, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol, 2016. 17: 464. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26968359/

112. Incrocci, L., et al. Hypofractionated versus conventionally fractionated radiotherapy for patients with localised prostate cancer (HYPRO): final efficacy results from a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol, 2016. 17: 1061. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27339116/

113. Catton, C.N., et al. Randomized Trial of a Hypofractionated Radiation Regimen for the Treatment of Localized Prostate Cancer. J Clin Oncol, 2017. 35: 1884. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28296582/

114. Koontz, B.F., et al. A systematic review of hypofractionation for primary management of prostate cancer. Eur Urol, 2015. 68: 683. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25171903/

115. Hocht, S., et al. Hypofractionated radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. Strahlenther Onkol, 2017. 193: 1. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27628966/

116. Greco, C., et al. Safety and Efficacy of Virtual Prostatectomy With Single-Dose Radiotherapy in Patients With Intermediate-Risk Prostate Cancer: Results From the PROSINT Phase 2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol, 2021. 7: 700. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33704378/

117. Bolla, M., et al. External irradiation with or without long-term androgen suppression for prostate cancer with high metastatic risk: 10-year results of an EORTC randomised study. Lancet Oncol, 2010. 11: 1066. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20933466/

118. Pilepich, M.V., et al. Androgen suppression adjuvant to definitive radiotherapy in prostate carcinoma–long-term results of phase III RTOG 85-31. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2005. 61: 1285. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15817329/

119. Roach, M., 3rd, et al. Short-term neoadjuvant androgen deprivation therapy and external-beam radiotherapy for locally advanced prostate cancer: long-term results of RTOG 8610. J Clin Oncol, 2008. 26: 585. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18172188/

120. D’Amico, A.V., et al. Androgen suppression and radiation vs radiation alone for prostate cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA, 2008. 299: 289. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18212313/

121. Denham, J.W., et al. Short-term neoadjuvant androgen deprivation and radiotherapy for locally advanced prostate cancer: 10-year data from the TROG 96.01 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol, 2011. 12: 451. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21440505/

122. Ash, D., et al. ESTRO/EAU/EORTC recommendations on permanent seed implantation for localized prostate cancer. Radiother Oncol, 2000. 57: 315. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11104892/

123. Martens, C., et al. Relationship of the International Prostate Symptom score with urinary flow studies, and catheterization rates following 125I prostate brachytherapy. Brachytherapy, 2006. 5: 9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16563992/

124. Matzinger, O., et al. Acute toxicity of curative radiotherapy for intermediate- and high-risk localised prostate cancer in the EORTC trial 22991. Eur J Cancer, 2009. 45: 2825. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19682889/

Author Correspondence:

Prof. Dr. Semir A. Salim. Al Samarrai

Medical Director of Professor Al Samarrai Medical Center.

Dubai Healthcare City, Al-Razi Building 64, Block D, 2nd Floor, Suite 2018

E-mail: semiralsamarrai@hotmail.com

Tel: +97144233669